Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Oral cavity cancers account for approximately 30% of all head and neck cancers, and squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histopathologic subtype. The National Cancer Institute estimated that in 2013, there were 41,380 new oral cancer cases and 7,890 oral cancer–related deaths in the United States. Even with advances in medical therapies, wide surgical resection of oral cavity cancers remains the primary treatment in most cases.

Dr. James Edmund Garretson, considered by many to be the father of oral and maxillofacial surgery, was one of the first American surgeons to describe local resection of oral cavity tumors in his 1869 treatise. Since then, thousands of surgeons have published their work on oral cancer surgery, but the premise of treatment remains unchanged: surgical extirpation with cancer-free margins is the mainstay of therapy.

This chapter highlights techniques in ablative and reconstructive surgery limited to the oral cavity and immediately adjacent structures.

History of the Procedure

Oral cavity cancers account for approximately 30% of all head and neck cancers, and squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histopathologic subtype. The National Cancer Institute estimated that in 2013, there were 41,380 new oral cancer cases and 7,890 oral cancer–related deaths in the United States. Even with advances in medical therapies, wide surgical resection of oral cavity cancers remains the primary treatment in most cases.

Dr. James Edmund Garretson, considered by many to be the father of oral and maxillofacial surgery, was one of the first American surgeons to describe local resection of oral cavity tumors in his 1869 treatise. Since then, thousands of surgeons have published their work on oral cancer surgery, but the premise of treatment remains unchanged: surgical extirpation with cancer-free margins is the mainstay of therapy.

This chapter highlights techniques in ablative and reconstructive surgery limited to the oral cavity and immediately adjacent structures.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

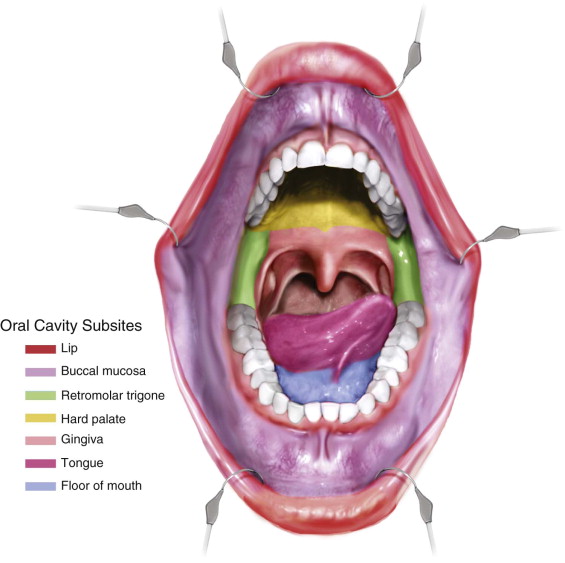

Resection of oral cavity tumors is the preferred method of treatment of T1 through T4a lesions, regardless of subsite ( Figure 98-1 ). Because tumor-free pathologic margins are associated with decreased local and regional recurrence rates and increased overall survival, wide surgical excision with at least a 1-cm margin is advised. Subsites of oral cavity cancers include the following:

-

Buccal mucosa

-

Retromolar trigone

-

Hard palate

-

Gingiva/alveolar ridge

-

Tongue

-

Floor of the mouth

-

Lip

Therapeutic neck dissection should be considered for patients with clinically apparent neck disease. About 20% to 30% of patients with oral cavity cancer and clinically negative findings in the neck harbor occult metastases; elective neck dissection can add a prognostic and therapeutic benefit for this subgroup of patients.

Technique: Site-Specific Surgical Management and Local Reconstruction Options

Buccal Mucosa

Before surgical management, all patients should undergo a thorough workup for accurate staging of the disease. This may include a thorough history and physical examination, fiberoptic pharyngoscopy/laryngoscopy, chest imaging, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck, incisional biopsies, possibly formal panendoscopy (see Chapter 96 ), dental evaluation, speech and swallow evaluation, and nutritional evaluation.

Resection of an oral malignancy is best performed under general endotracheal anesthesia for the patient’s comfort and to allow adequate access and retraction of the lips, cheeks, tongue, and other oral structures. Small lesions can be excised under local anesthesia in a clinic setting; however, both the patient and surgeon must accept that this represents an excisional biopsy, with the possibility of more formal resection and perhaps neck dissection pending the final pathologic report and margin assessment.

Step 1:

Marking

A marking pen is used to draw a planned mucosal incision with 1-cm circumferential margins from the visible and palpable tumor. If the planned resection involves Stensen’s duct, a sialodochoplasty may be necessary in reconstruction. Submucosal infiltration of a local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor aids in hemostasis. It is important not to penetrate the tumor when giving the injection. A contralateral Molt mouth prop and Adson-Beckman retractors may be used to expose the surgical site.

Step 2:

Mucosal Incision

Incision with needle tip electrocautery along the marked line is completed to underlying connective tissue. Care is taken not to handle the mucosal edge of the specimen aggressively because this may interfere with the histopathologic analysis of margins.

Step 3:

Circumferential Resection

Gentle opposite traction of the wound edges with toothed Cushing forceps is used to visualize the path of excision. Needle tip electrocautery is used to deepen the incision through connective tissue and the buccinator muscle, remaining at least 1 cm from the tumor’s edge. Using digital palpation, the surgeon should frequently check that the incision is not deviating toward the tumor, both in circumference and depth.

Step 4:

Deep Resection

Depending on preoperative imaging and bimanual palpation, the depth of resection is determined. If the overlying cheek skin is involved, fixed to the tumor, or closer than 1 cm to the deep margin of the tumor, it should be excised en bloc with the intraoral buccal mucosal component. If a surgical plane exists between the tumor and cheek skin, a full-thickness resection may not be necessary. In such cases, it is important to be aware of the depth of the tumor so as to remove it successfully with oncologically sound margins. This often involves resection of the underlying buccinator muscle and may include subcutaneous fat with the specimen.

Step 5:

Intraoperative Margin Evaluation

Metzenbaum scissors are used to excise a thin circumferential mucosal margin, in addition to a deep margin to be evaluated by the pathologist. These should not be excised with electrocautery because the heat will shrink and deform the small amount of tissue, making accurate histologic analysis difficult. Samples are sent fresh to the pathology lab to be evaluated by frozen section. If a margin returns “close” or positive for tumor, wider resection may be necessary.

Step 6:

Reconstruction

Small resection beds with viable underlying muscle may be amenable to granulation and healing by secondary intention. Larger defects may be reconstructed with a skin graft. Through-and-through defects may require intraoral and facial local rotational flaps. The buccal fat pad (BFP) flap is an excellent local option for reconstructing many buccal defects, given its proximity to the defect, ease of harvest, hearty blood supply, and minimal donor site morbidity.

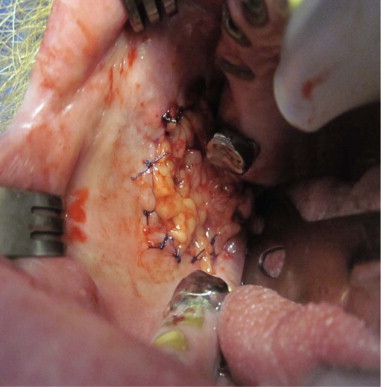

The buccal lobe of the BFP lies between the buccinator and masseter muscles surrounding Stensen’s duct and can readily be mobilized for defect coverage. A curved hemostat can be used to bluntly dissect through the buccinator muscle just inferior to Stensen’s duct. The bright yellow fat pad will begin to herniate into the wound. Circumferential blunt dissection may be necessary to fully mobilize the fat. Gentle traction with a McIndoe forceps allows the flap to advance into the wound. Care should be taken to handle the fat pad gently because excessive traction or maceration can cause the flap to lose its structure. Once enough width and length to cover the defect without tension has been harvested, the flap is circumferentially inset with 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin interrupted sutures to the mucosal margin. Over time, epithelium granulates in over the exposed fat pad, and the underlying fat provides bulk to the cheek ( Figure 98-2 ).

ALternative Technique 1: Mandibular Gingiva/Alveolus/Retromolar Trigone

Step 1:

Marking

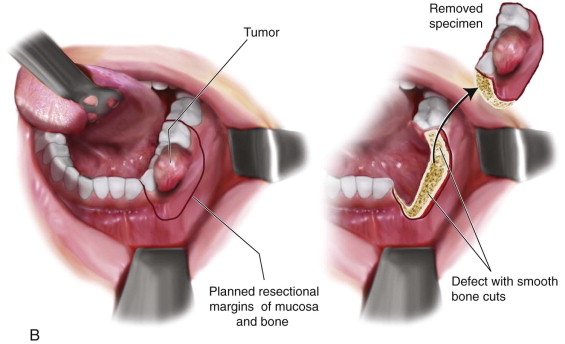

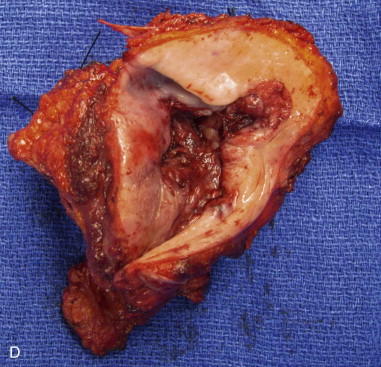

A marking pen is used to draw a planned mucosal incision with 1-cm circumferential margins from the visible and palpable tumor. Determination of bony resection should be made based on clinical and radiographic examination. If teeth are present, the surgeon should plan to extract teeth in the line of osteotomy or plan to create an interdental osteotomy during the marginal or segmental resection ( Figure 98-3, A ).

Step 2:

Mucosal Incision

Needle tip electrocautery is used to create a mucosal incision along the planned circumferential resection. Over the alveolus, this should be carried down through the periosteum to disease-free bone. As the incision extends to the floor of the mouth and buccal vestibular mucosa, the dissection is supraperiosteal to maintain a safe distance from the tumor.

Step 3:

Circumferential Soft Tissue Resection

The surgeon should leave an adequate cuff of soft tissue around the tumor before approaching the mandible. If a marginal mandibulectomy is planned, a periosteal incision should be made on the buccal and lingual aspects of the mandible where the osteotomy is planned. From this incision, it is important not to reflect periosteum and soft tissue toward the tumor because this would violate the surgical margins.

Step 4:

Osteotomy

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses