History of the Procedure

The history of thyroid goiters dates back to 2700 bc , when the Chinese first suggested seaweed and sea sponge, a significant source of iodine, as remedies. More than a thousand years later, the Romans discussed and documented an operative treatment for an enlarged thyroid. It seems natural that around 1500 ad , Leonardo da Vinci was one of the first artists to draw an anatomically accurate and detailed healthy thyroid. Surgery on the thyroid continued to fail, however. In the late 1800s, Samuel Gross warned that “every stroke of the knife will be followed by a torrent of blood and lucky it would be for him if his victim lived long enough for him to finish his horrid butchery. No honest and sensible surgeon would ever engage in it.” Theodor Billroth, in 1881, noted that these procedures were “a matter of no little difficulty.” It was not until later in the nineteenth century that Theodor Kocher developed operative techniques and used the new techniques of antisepsis to lower the morbidity and mortality of these operations. In so doing, thyroidectomy surgeries would reach a nadir mortality rate of less than 1% by the middle of the twentieth century.

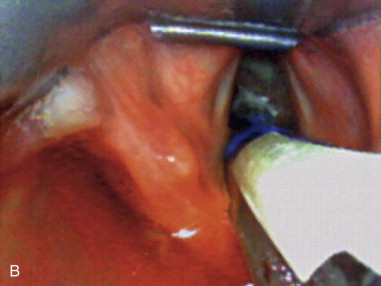

With the morbidity and mortality minimized, the surgical approach became the next variable challenge. Miccoli and his group at the University of Pisa are responsible for developing a surgical approach, in 1998, that relies on endoscopic and ultrasonic technology, which is easily the most widely practiced technique today by minimal-access surgeons around the globe. Although optional approaches such as robotic-assisted or endoscopic thyroidectomy remain, the following describes the conventional open approach.

History of the Procedure

The history of thyroid goiters dates back to 2700 bc , when the Chinese first suggested seaweed and sea sponge, a significant source of iodine, as remedies. More than a thousand years later, the Romans discussed and documented an operative treatment for an enlarged thyroid. It seems natural that around 1500 ad , Leonardo da Vinci was one of the first artists to draw an anatomically accurate and detailed healthy thyroid. Surgery on the thyroid continued to fail, however. In the late 1800s, Samuel Gross warned that “every stroke of the knife will be followed by a torrent of blood and lucky it would be for him if his victim lived long enough for him to finish his horrid butchery. No honest and sensible surgeon would ever engage in it.” Theodor Billroth, in 1881, noted that these procedures were “a matter of no little difficulty.” It was not until later in the nineteenth century that Theodor Kocher developed operative techniques and used the new techniques of antisepsis to lower the morbidity and mortality of these operations. In so doing, thyroidectomy surgeries would reach a nadir mortality rate of less than 1% by the middle of the twentieth century.

With the morbidity and mortality minimized, the surgical approach became the next variable challenge. Miccoli and his group at the University of Pisa are responsible for developing a surgical approach, in 1998, that relies on endoscopic and ultrasonic technology, which is easily the most widely practiced technique today by minimal-access surgeons around the globe. Although optional approaches such as robotic-assisted or endoscopic thyroidectomy remain, the following describes the conventional open approach.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

There are multiple indications for thyroidectomy, ranging from benign to malignant; in addition, the extent of thyroidectomy surgery still remains a controversy for some. Overall, surgical resection for malignancy is the standard of care. Yet intervention for benign goiters varies depending on symptoms such as airway impedance or obstruction, dysphagia; or invasion of local vessels. Other indications of surgery for benign disease include hyperthyroid nodule and (refractory) Graves disease, as it may decrease antibody levels and slow or stop further related exophthalmos and vision impairment.

Surgical Workup

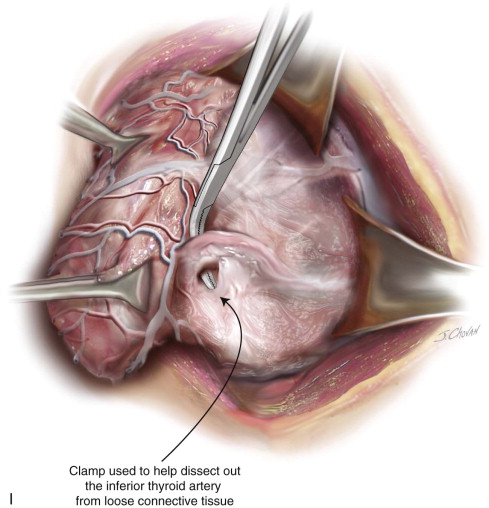

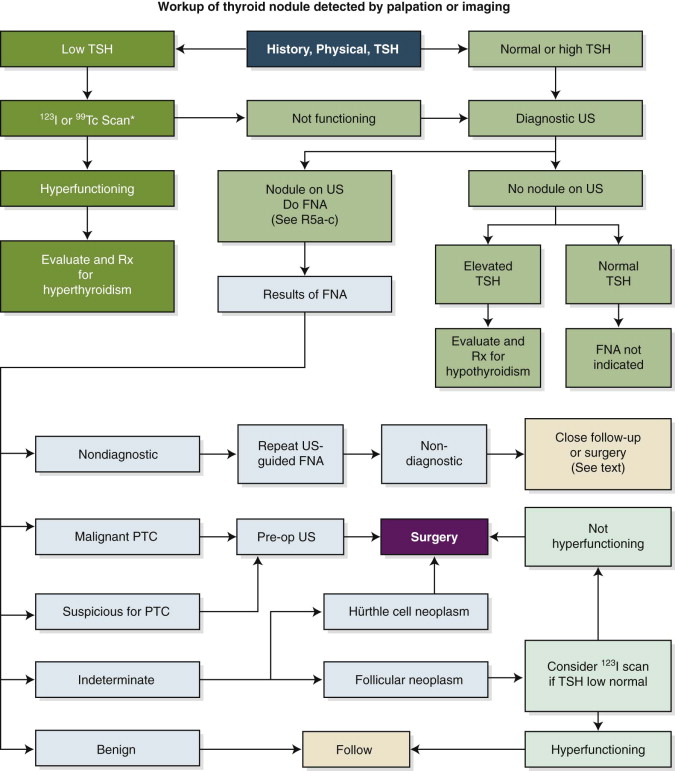

After obtaining a thorough history (including asking about childhood head and neck irradiation, total body irradiation for bone marrow transplantation, a family history of thyroid abnormalities, exposure to ionizing radiation, and rapid growth or hoarseness) from the patient, the physician performs a physical exam, concentrating on the head and neck regions but not ignoring other physical findings of an abnormally functioning thyroid; we recommend a blood test and imaging. As outlined by the 2009 American Thyroid Association guidelines, we begin by checking a thyroid-stimulating hormone level then follow accordingly ( Figure 89-1 ).

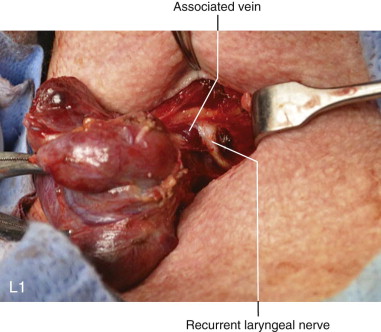

It is imperative for a physician performing thyroidectomies to evaluate the vocal cords prior to any surgery even in the absence of voice or swallowing complaints, as demonstrated by two studies where 32% to 66% of asymptomatic preoperative patients were found to have a vocal cord paresis. This evaluation may be accomplished via indirect mirror or direct flexible laryngoscopy.

Limitations and Contraindications

Total thyroidectomy will permanently leave the patient hypothyroid and require lifelong thyroid hormone replacement; this should be considered in underserved areas of the world where thyroid hormone replacement may not be readily available. Contraindications include uncontrolled severe hyperthyroidism, as this may lead to intraoperative or immediate postoperative thyroid storm. Pregnancy is usually a contraindication with the exception of airway obstruction or aggressive cancer, due to anesthesia exposure to the fetus, as well as risk of cretinism without proper thyroid hormone replacement. When possible, surgery should be performed no earlier than the second trimester of pregnancy. Less common contraindications for surgery include a benign thyroid nodule with contralateral vocal cord paralysis, or previously uncontrolled hypocalcemia.

Technique: Total Thyroidectomy

Step 1:

Incision Location

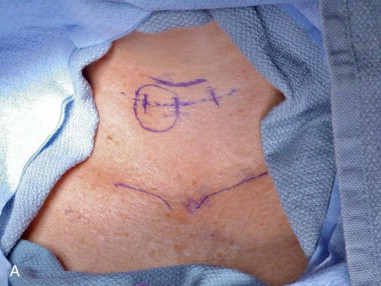

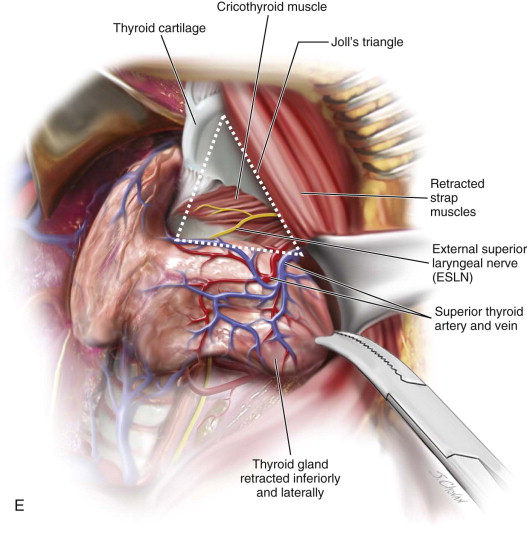

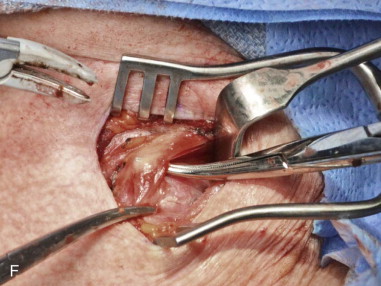

In the preoperative unit with the patient in an upright position, a midline 4-cm planned incision is marked in a natural skin crease below or at the level of the cricoid cartilage to best camouflage the scar. The incision can be lengthened for large goiters or complicated cases ( Figure 89-2, A ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses