Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The carotid body is a small cluster of chemoreceptor cells that develops from the neural crest located at the bifurcation of the carotid artery. Carotid body tumors are highly vascularized neoplasms that arise from these cells (paraganglioma). The carotid body tumor was first described by Von Haller in 1743. These tumors were also reported by Von Luschka in 1862. In 1891, Marchand described the first removal of a carotid body tumor, performed by Reigner in 1880. The patient did not survive. In 1886, Maydl reported the resection of a carotid body tumor, stating that the patient became aphasic and hemiplegic. In 1903, Scudder produced the first report of a successful resection of a tumor of carotid body origin in the American literature. Removal of carotid body tumors was considered mandatory in the first part of the twentieth century because many authors, such as Wilson et al., pointed out that 50% of these tumors were histologically malignant. In 1950, Monro reported a 29% mortality rate in a review of 223 cases. Hollenberg urged caution in the removal of carotid body tumors, stating that it should be done only if ligation of the carotid artery were possible.

In 1953, James pointed out that the treatment of these tumors should be surgical resection, except in patients with a potential risk of mortality or postoperative morbidity. The current consensus is that most carotid body tumors are benign, have a low incidence of malignancy, and grow slowly, with compression of the surrounding structures. It is thought that excision of the tumor can be safely performed in most cases without interrupting the carotid circulation by using the subadventitial approach, although in rare cases excision of the tumor may require internal carotid artery resection with graft replacement. In selected cases of asymptomatic patients with no increase in the tumor’s size, a conservative approach can be adopted. Radiotherapy is reserved for large inoperable tumors.

History of the Procedure

The carotid body is a small cluster of chemoreceptor cells that develops from the neural crest located at the bifurcation of the carotid artery. Carotid body tumors are highly vascularized neoplasms that arise from these cells (paraganglioma). The carotid body tumor was first described by Von Haller in 1743. These tumors were also reported by Von Luschka in 1862. In 1891, Marchand described the first removal of a carotid body tumor, performed by Reigner in 1880. The patient did not survive. In 1886, Maydl reported the resection of a carotid body tumor, stating that the patient became aphasic and hemiplegic. In 1903, Scudder produced the first report of a successful resection of a tumor of carotid body origin in the American literature. Removal of carotid body tumors was considered mandatory in the first part of the twentieth century because many authors, such as Wilson et al., pointed out that 50% of these tumors were histologically malignant. In 1950, Monro reported a 29% mortality rate in a review of 223 cases. Hollenberg urged caution in the removal of carotid body tumors, stating that it should be done only if ligation of the carotid artery were possible.

In 1953, James pointed out that the treatment of these tumors should be surgical resection, except in patients with a potential risk of mortality or postoperative morbidity. The current consensus is that most carotid body tumors are benign, have a low incidence of malignancy, and grow slowly, with compression of the surrounding structures. It is thought that excision of the tumor can be safely performed in most cases without interrupting the carotid circulation by using the subadventitial approach, although in rare cases excision of the tumor may require internal carotid artery resection with graft replacement. In selected cases of asymptomatic patients with no increase in the tumor’s size, a conservative approach can be adopted. Radiotherapy is reserved for large inoperable tumors.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Three different types of carotid body tumors (CBTs) have been described: familial, sporadic, and hyperplastic. The sporadic form is the most common type (about 85% of CBTs). The familial type (10% to 15%) is more common in younger patients, and the hyperplastic form affects patients with chronic hypoxia. Association with syndromes such as Von Hippel–Lindau disease, neurofibromatosis type I, multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) 2A, and MEN 2B has been found. A molecular basis has been suggested. Mutation in six genes has been described, which can be related to the development of some paragangliomas.

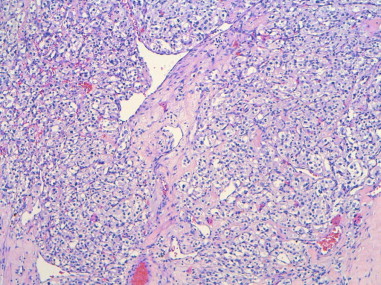

Carotid body tumors consist of a nest of epithelioid cells (type I cells), often with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, that are arranged in groups called Zellballen. These are surrounded by a flattened layer of sustentacular cells (type II cells), which are positive for S-100 protein. Although a minority of cases are described as histologically malignant, the pathologic features cannot predict the biologic behavior ( Figure 93-1 ).

Complete surgical excision of the carotid body tumor is indicated because it is the only therapeutic option that provides immediate control of the disease, although tumor recurrence has been reported in 2.9% of cases after a presumed total resection. In large hypervascularized tumors with involvement of critical vascular and neural structures, an attempt at total resection may be associated with bleeding and a high rate of morbidity and eventual mortality. Whether surgery is indicated depends on the patient’s symptoms, the size and location of the tumor, the patient’s age and general condition, and the risk of postoperative neurologic impairment.

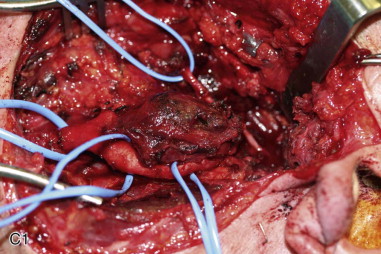

The Shamblin classification system categorizes carotid body tumors into three classes, providing a tool for predicting the surgical difficulty of the resection. Class I tumors are small and minimally attached to the vessels and thus are easily dissected. Class II tumors are more adherent to the adventitia and partially surround the vessels, making resection more difficult. Class III tumors are large and adherent to the carotid bifurcation; they enclose the carotid vessels, making conservative resection impossible. Although single-stage resection is the state of the art, staged surgery has also been used, mainly for tumors greater than 2 cm with intracranial involvement.

Limitations and Contraindications

Although surgical treatment is the gold standard for carotid body tumors, there are some limitations. Simultaneous treatment of a bilateral glomus tumor is contraindicated because blood pressure maintenance could be compromised by bilateral carotid body denervation. Other contraindications include removal of carotid body tumors in patients at high risk of stroke related to a potential carotid resection or ligation, elderly patients, and malignant tumors with intracranial extension. Radiotherapy has been used to control tumor growth in patients who cannot undergo surgery.

Technique: Resection of a Carotid Body Tumor

Step 1:

Intubation

Oral intubation is indicated. Nasotracheal intubation is not necessary. Communication between the surgeon and anesthesiologist during surgery is important because management of the anesthesia is challenging. Surgical manipulation can be associated with catecholamine secretion, with severe hemodynamic instability.

Step 2:

Incision

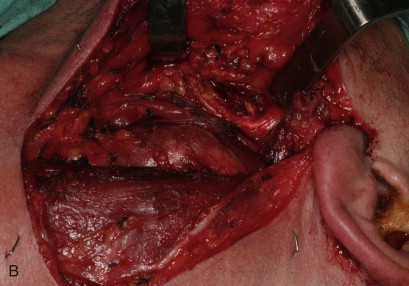

The incision should be based on the size of the tumor. Usually, exposure is achieved through a horizontal incision along the cervical creases in the midneck. For large tumors that extend superiorly, the incision may need to extend into the preauricular area. For elevation of skin flaps, careful dissection in a subplatysmal plane should be carried out to avoid injury to the mandibular branch of the facial nerve or greater auricular nerve ( Figure 93-2, A ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses