Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

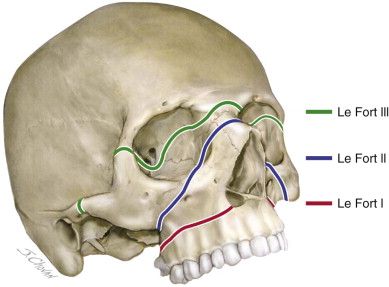

The treatment of midfacial injuries was first described extensively in the nineteenth century. In 1823, von Graefe reported the first external splinting for a maxillary fracture. In 1866, Guerin described the midfacial fracture pattern, noting involvement of the maxilla, the pyramidal part of the palatine bone, and pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone. He noted an association with ecchymosis near the greater palatine foramen, which is termed Guerin’s sign. In 1901, Rene Le Fort reported on his experiments on 35 cadaver heads that he subjected to various degrees of trauma. His classification system of three patterns of maxillary fracture has been paramount in developing reconstructive strategies in trauma, craniofacial, and orthognathic surgery ( Figure 76-1 ).

Major advancements in the management of maxillary fractures in the twentieth century coincided with times of war. During World War I, Fry and Gillies pioneered the treatment of maxillofacial injuries with collaboration between the anesthetist and surgeon. During World War II, Le Fort fractures were treated by external fixation from metal splints to a headcap through rods and machined universal joints. In 1942, Adams introduced internal fixation for maxillary fractures, using suspension wires from the zygomatic process of the frontal bone, inferior orbital rim, or zygomatic bone. The development of osteosynthesis heralded the advent of modern traumatology. Automatic compression plates were introduced by Luhr in 1968 and standardized by Spiessel in 1971. The principles of monocortical miniplate fixation without axial compression that were proposed by Michelet and Moll (1971) and Champy and Lodde (1976) have been applied to the midface. Gruss (1982) and Manson and colleagues (1985) discussed the stabilization of buttresses with miniplates and proposed systematic approaches to the treatment of midfacial and panfacial fractures.

History of the Procedure

The treatment of midfacial injuries was first described extensively in the nineteenth century. In 1823, von Graefe reported the first external splinting for a maxillary fracture. In 1866, Guerin described the midfacial fracture pattern, noting involvement of the maxilla, the pyramidal part of the palatine bone, and pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone. He noted an association with ecchymosis near the greater palatine foramen, which is termed Guerin’s sign. In 1901, Rene Le Fort reported on his experiments on 35 cadaver heads that he subjected to various degrees of trauma. His classification system of three patterns of maxillary fracture has been paramount in developing reconstructive strategies in trauma, craniofacial, and orthognathic surgery ( Figure 76-1 ).

Major advancements in the management of maxillary fractures in the twentieth century coincided with times of war. During World War I, Fry and Gillies pioneered the treatment of maxillofacial injuries with collaboration between the anesthetist and surgeon. During World War II, Le Fort fractures were treated by external fixation from metal splints to a headcap through rods and machined universal joints. In 1942, Adams introduced internal fixation for maxillary fractures, using suspension wires from the zygomatic process of the frontal bone, inferior orbital rim, or zygomatic bone. The development of osteosynthesis heralded the advent of modern traumatology. Automatic compression plates were introduced by Luhr in 1968 and standardized by Spiessel in 1971. The principles of monocortical miniplate fixation without axial compression that were proposed by Michelet and Moll (1971) and Champy and Lodde (1976) have been applied to the midface. Gruss (1982) and Manson and colleagues (1985) discussed the stabilization of buttresses with miniplates and proposed systematic approaches to the treatment of midfacial and panfacial fractures.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Maxillary fractures most frequently occur as a result of blunt trauma from assault, sporting injuries, and motor vehicle accidents. The Le Fort I fracture is a horizontal maxillary fracture resulting from a blow to the maxilla above the root apices. It involves the nasal septum, lateral nasal walls, anterior and lateral walls of the maxillary sinus, and pterygoid plates. The Le Fort II fracture pattern describes a pyramidal fracture resulting from blunt trauma to the infraorbital rim and nasofrontal junction. The central midface and maxilla are mobilized from the facial skeleton with the fracture line extending through the nasofrontal suture, frontal process of maxilla, lacrimal bone, inferior orbital rim, anterior wall of the maxillary sinus, and pterygoid plates. The Le Fort III fracture or craniofacial dysjunction results from high-impact blunt trauma to the nasofrontal junction and upper lateral orbital rims. The facial skeleton is separated from the cranial base, with the fracture line extending medially through the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, the vomer, and base of sphenoid, and laterally through the nasofrontal suture, medial orbital wall, orbital floor, zygomaticofrontal junction, and zygomatic arch. The continuum from Le Fort I to Le Fort III reflects an increasing severity of injury, increasing complexity of repair (with additional access requirements), and increasing likelihood for concomitant neurologic and ocular injury.

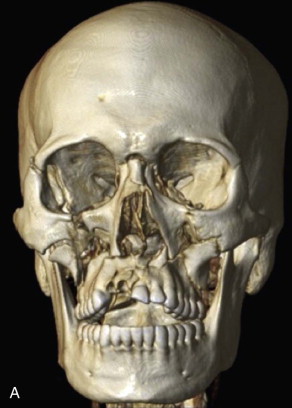

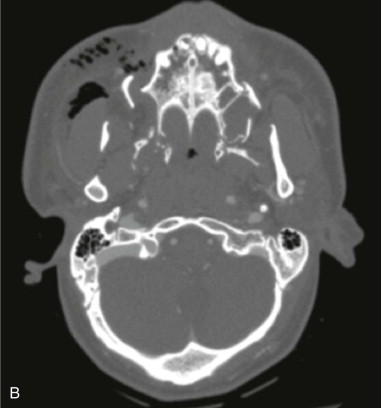

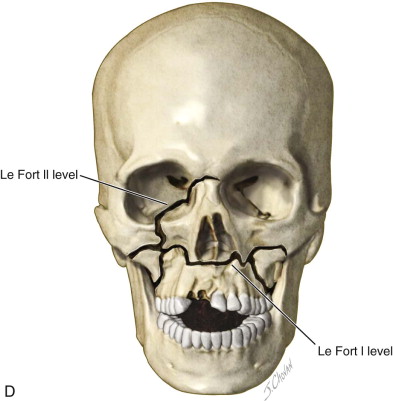

Ideally, surgical management of midfacial fractures should be completed as soon as the patient’s medical status allows. Preoperative assessment includes clinical examination and radiographic evaluation with noncontrast computed tomography reformatted in three planes with a slice thickness of 1 mm or less ( Figure 76-2, A and B ). Goals of treatment include reestablishing premorbid occlusion and facial width, projection, and height. Failure to repair Le Fort fractures can result in midface retrusion, midface elongation, and anterior open bite due to the posteroinferior pull of the medial pterygoid on the posterior maxilla ( Figure 76-2, C ). In addition, unrepaired orbital fractures of Le Fort II and III injuries can lead to enophthalmos, diplopia, and impaired lacrimal drainage. Early reconstruction allows for optimal restoration of the preinjury appearance as determined by the relationship between bone and soft tissue. Mobilization and reduction of osseous segments can be challenging in the delayed setting due to bone fragment impaction and soft tissue contraction. In addition, delayed reconstruction results in a second insult to the contused soft tissue and may increase subcutaneous fibrosis, rigidity, and hyperpigmentation.

It should be emphasized that “pure” Le Fort fractures that follow the lines of Figure 76-1 exactly are relatively uncommon in clinical settings. Le Fort injuries more often occur in a variety of permutations and combinations. For example, a patient may present with a left Le Fort I fracture and a right Le Fort II fracture ( Figure 76-2, D ). Unilateral or hemi–Le Fort injuries, comminuted fractures, and associated palatal fractures are also encountered.

Limitations and Contraindications

Le Fort injuries occur with high-impact force; as such, patients often have concomitant or life-threatening injuries. Initial management of patients with suspected maxillofacial fractures should follow Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol. The primary survey includes airway and cervical spine stabilization, breathing and ventilatory support, circulation and hemorrhage control, disability and neurologic evaluation, and exposure and environment control (ATLS). Airway obstruction in Le Fort injuries mainly occurs secondary to hemorrhage into the upper airway from multiple sources, as well as altered airway anatomy with posteroinferior displacement of the midface into the oropharyngeal airway. The incidence of life-threatening hemorrhage in Le Fort II and III injury is greater than that for all other facial injuries with rates of 5.5% as compared to 1.2%, respectively. Airway protection and intubation should be considered in the setting of a significant pooling of blood in the oronasal cavity and a high risk of life-threatening aspiration and airway obstruction. Up to one third of Le Fort injuries may require emergent airway; therefore, clinicians treating midface trauma should be prepared to establish a surgical airway both acutely and in more controlled settings. Mild to moderate hemorrhage may be controlled with nasal packing or tamponade with a balloon catheter. However, severe hemorrhage that is not resolved with local measures may necessitate transcatheter arterial embolization.

Le Fort fractures are also infrequently associated with cervical spine injury, with reported incidences of 1.5 to 2%. In addition, midfacial fractures often present with traumatic brain injury with an incidence of 51%. Le Fort fractures are more strongly associated with death from neurologic injury as compared with isolated mandible fractures. The evaluation of maxillofacial fractures is part of the secondary survey and follows stabilization and resuscitation of the multisystem trauma patient. In Le Fort II and III fractures with orbital components, ophthalmologic evaluation of possible globe injury should be completed prior to surgery.

Technique: Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Le Fort Fracture

In general, the management of Le Fort fractures follows the principles of wide exposure and direct viewing of fracture segments, the use of vertical and horizontal buttresses of the face for alignment and fixation, and immediate bone grafting to reconstruct comminuted or avulsed bony structures.

Step 1:

Airway Management

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses