Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Comminuted mandibular fractures occur when an excessive amount of force, and associated energy transfer, occurs to the osseous structures of the mandible. Frequently caused today by motor vehicle accidents or striking a rigid, nonmoveable structure, these fractures have been seen in Europe since the introduction of gunpowder and ballistic projectiles to warfare in the fourteenth century. The historical treatment of comminuted mandibular fractures focused on the principle of closed management, used primarily to avoid stripping the periosteum and subsequent blood supply from the comminuted bony segments. A variety of surgical techniques, such as maxillomandibular fixation (MMF), surgeon-fabricated occlusal splints or Gunning splints, and extraoral skeletal pins, were used, with varying degrees of success and patient outcomes. Kazanjian was the first to challenge this notion, based on his observations of maxillofacial injuries sustained in World War I. He noted, “The majority of nonunited fractures of are due to inadequate immobilization of comminuted fragments of bone, and subsequent infection, rather than to the initial loss of bone.” He believed that stabilization of the bony segments was the critical step in obtaining union and consolidation of the comminuted osseous fragments. Kazanjian’s theories subsequently led to the development of numerous techniques for maintaining the reduced fracture segments in position, eventually leading to the current modality of open reduction and rigid internal fixation with surgical plates and screws.

History of the Procedure

Comminuted mandibular fractures occur when an excessive amount of force, and associated energy transfer, occurs to the osseous structures of the mandible. Frequently caused today by motor vehicle accidents or striking a rigid, nonmoveable structure, these fractures have been seen in Europe since the introduction of gunpowder and ballistic projectiles to warfare in the fourteenth century. The historical treatment of comminuted mandibular fractures focused on the principle of closed management, used primarily to avoid stripping the periosteum and subsequent blood supply from the comminuted bony segments. A variety of surgical techniques, such as maxillomandibular fixation (MMF), surgeon-fabricated occlusal splints or Gunning splints, and extraoral skeletal pins, were used, with varying degrees of success and patient outcomes. Kazanjian was the first to challenge this notion, based on his observations of maxillofacial injuries sustained in World War I. He noted, “The majority of nonunited fractures of are due to inadequate immobilization of comminuted fragments of bone, and subsequent infection, rather than to the initial loss of bone.” He believed that stabilization of the bony segments was the critical step in obtaining union and consolidation of the comminuted osseous fragments. Kazanjian’s theories subsequently led to the development of numerous techniques for maintaining the reduced fracture segments in position, eventually leading to the current modality of open reduction and rigid internal fixation with surgical plates and screws.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

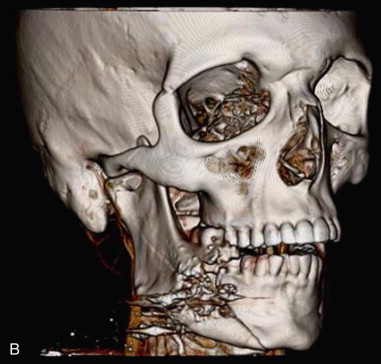

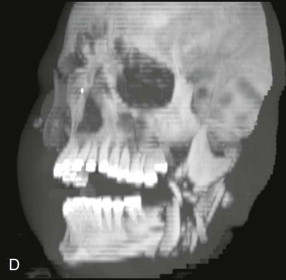

For craniomaxillofacial trauma surgeons, the current clinical presentation of comminuted mandibular fractures occurs secondary to a significant energy transfer to a localized region of the mandible, usually as the result of a motor vehicle accident, striking or being struck by an immoveable object, or a gunshot wound. As noted by Alpert et al, approximately 5% to 7% of all mandibular fractures present with comminution; therefore, the craniomaxillofacial trauma surgeon must be knowledgeable about the proper management of these conditions. The overwhelming majority of gunshot wounds encountered in the civilian trauma setting are caused by low-velocity, low–energy transfer handguns and do not display the characteristic soft tissue changes seen in modern high-velocity/ultra-high-velocity ballistic injuries sustained in military conflicts ( Figure 69-1 ). These injuries can produce debilitating soft tissue avulsions, sequential necrosis, and loss of tissue over the course of several days after injury, which complicate both the short-term and long-term management of these patients. The closest civilian corollary to these injuries is seen in patients who have attempted suicide, or been shot at close range (Sherman-Parrish class III), with a shotgun ( Figure 69-2 ).

Limitations and Contraindications

Avulsive tissue loss, with resultant exposure of any underlying surgical hardware, is an obvious limitation in the management of comminuted fractures. Definitive plans for reconstruction of the osseous skeleton must be coordinated with concurrent planning for recruitment of soft tissue to the site of tissue avulsion. If rigid internal fixation is the preferred management technique for a comminuted fracture, the fragmented portions of the mandible cannot be subjected to masticatory functional loads. The surgeon must adhere to two basic tenets of treatment. First, the fixation must support the entire functional load (i.e., the principle of load-bearing osteosynthesis). The selected surgical plate must be of a sufficient size and strength to withstand the functional forces applied to it. Second, absolute stability of the reconstruction construct must be achieved. In comminuted fractures, the small bone fragments cannot take part of the functional load, as is seen in load-sharing osteosynthesis, nor can they be compressed due to risks of sequestration and devitalization.

Technique: Surgical Treatment of the Comminuted Mandibular Fracture

Step 1:

Intubation and Induction of General Anesthesia

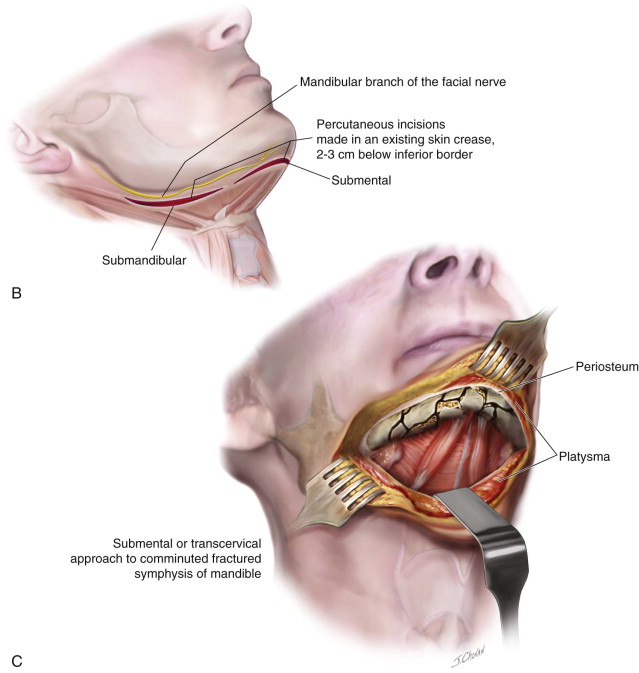

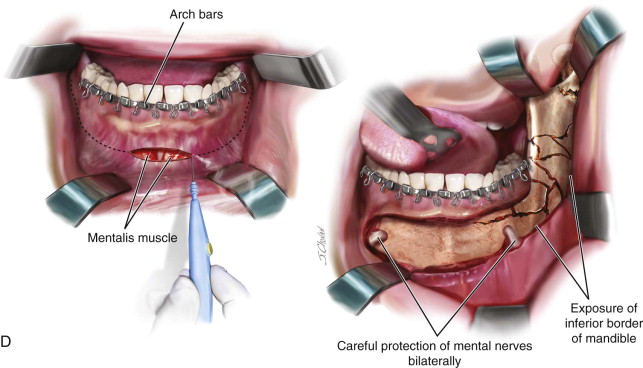

Coordination with the anesthesia team in the preoperative setting is an important component of therapy. Nasotracheal intubation affords the greatest flexibility to establish a functional occlusion and minimize the interference with the endotracheal tube commonly seen in conventional orotracheal intubation. If the patient is partially dentate or completely edentulous, consideration can be given to oral intubation, especially in the case of concurrent midfacial trauma and anesthesia concerns with potential nasal intubation. If the patient is completely dentate and has concurrent midfacial trauma that prevents nasotracheal intubation, consideration must be given to surgical tracheostomy or submental pull-through techniques. If the surgeon will be approaching the comminuted mandibular fracture via percutaneous incisions, communication regarding the use of neuromuscular blocking agents must occur before initiation of the surgical approach to allow for identification of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve.

Step 2:

Application of Arch Bars and Establishment of a Functional Occlusion

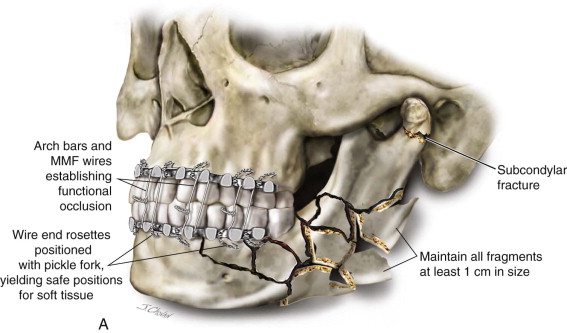

After administration of a local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor to establish hemostasis and for prolonged anesthesia, the establishment of arch bars is accomplished in the standard fashion with 24-, 26-, and/or 28-gauge stainless steel surgical wires. Use of the smaller-diameter wires increases the risk of fatigue fracture and wire breakage. Retraction of the cheeks can be facilitated with the use of either a Minnesota retractor or self-retaining plastic cheek retractors. Tightening of the wires is accomplished with wire drivers or needle drivers, based on the surgeon’s preference, and rosettes at the terminal end of the wire are positioned with a pickle fork to prevent mucosal and labial trauma. Retraction of the tongue to gain access to the lingual borders of the mandible is accomplished with a Weider (sweetheart) retractor. The use of mouth props should be minimized to eliminate potential distraction/displacement of the fracture segments. Use of the newly marketed screw-retained arch bar systems is contraindicated in the mandible due to disruption of the occlusal table and comminution at the site of screw placement; however, these systems may be considered for use in an intact maxilla to expedite placement of fixation. MMF is established with either dental elastics or surgical wires through the lugs of the arch bars. Grossly unstable or nonsalvageable dentition should be removed at this time ( Figure 69-3, A ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses