Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The most important factor affecting the outcome of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the presence of cervical lymph node metastasis at diagnosis. Approximately 30% of patients with oral cancer who present without clinical or radiographic evidence of regional disease in fact harbor occult cervical metastasis. This has led most investigators to recommend that patients with OSCC undergo elective, selective neck dissection of the clinically N0 neck if they have primary tumors that demonstrate clinical prognostic indicators of metastasis, such as a size greater than 2 cm in diameter or a depth of invasion greater than 2 to 4 mm. Selective neck dissection in the clinically N0 patient is beneficial when tumor is found on pathologic evaluation of the specimen; this allows for early removal of metastatic disease and accurate staging information on which to base adjuvant therapy. Unfortunately, this approach has led to unnecessary surgery in 65% to 75% of patients with early-stage OSCC. Additionally, neck dissection is associated with neurogenic shoulder dysfunction and esthetic deformity in a significant number of individuals. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is a minimally invasive technique that is currently under investigation for staging of OSCC. It offers the potential for reducing the morbidity associated with selective neck dissection.

Seaman and Powers published the first report of lymphatic mapping for cancer patients in 1955. They described the injection of breast tumors with radiolabeled colloidal gold and mapped the progression of the tracers through the regional lymphatics. Five years later, Gould et al. coined the term “sentinel node” to describe a level II cervical lymph node consistently identified during parotidectomy for malignant tumors; the status of this node guided the surgeons to complete or forego neck dissection.

The concepts of a “sentinel lymph node” and lymphatic mapping were first used to reliably and accurately predict regional cancer spread by Morton et al. in 1992. This group reported data from 223 patients with stage I cutaneous melanoma in which a vital blue dye–directed sentinel node identification and regional lymphadenectomy were performed. Lymphoscintigraphy was used in ambiguous sites. In the study, 194 sentinel nodes were identified in 237 nodal basins; only two nonsentinel nodes were the site of metastasis in specimens with a negative sentinel node (a false-negative rate of less than 1%). This established sentinel lymph node biopsy as an accurate staging procedure for early-stage cutaneous melanoma.

SLNB for cutaneous melanoma and breast cancer has become widely accepted as a less invasive staging procedure for early primary tumors. More recently, it has shown promise in accurately predicting and staging regional lymphatics in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). In 1996, Alex and Krag identified a sentinel node using gamma probe localization from a laryngeal cancer. In 1998, Koch et al. and Pittman et al. used a radioactive colloid tracer and isosulfan blue dye, respectively, to identify sentinel nodes in HNSCC, with equivocal results. One year later, Shoaib et al. combined the two modalities (radiotracer and dye) and identified the sentinel node in 15 of 16 patients with clinically negative necks with OSCC; they also accurately detected 100% of occult neck disease.

Multiple single-center pathologic validation studies on SLNB in oral cancer suggest that it is efficacious for the identification of sentinel lymph nodes, that it is capable of detecting occult metastasis, and that it accurately predicts the status of the lymphatic basins draining the primary tumor in some patients, with negative predictive values between 90% and 98%. Two consensus conferences and a meta-analysis of the existing data suggested an evolving role for SLNB in the staging of OSCC, and recommendations for pathologic processing were made. A prospective trial in six European centers that studied SLNB either alone or followed by neck dissection resulted in upstaging of 34% of the oral cancer patients and demonstrated a false-negative rate of 7.1%. The results of the ACOSOG Z0360 validation trial, recently published, showed that for T1 or T2 oral squamous cell carcinoma, SLNB with serial step sectioning (SSS) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) resulted in a negative predictive value of 96%. The authors concluded that it is reasonable to initiate clinical trials involving SLNB, with completion of neck dissection only in selected OSCC patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes.

History of the Procedure

The most important factor affecting the outcome of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the presence of cervical lymph node metastasis at diagnosis. Approximately 30% of patients with oral cancer who present without clinical or radiographic evidence of regional disease in fact harbor occult cervical metastasis. This has led most investigators to recommend that patients with OSCC undergo elective, selective neck dissection of the clinically N0 neck if they have primary tumors that demonstrate clinical prognostic indicators of metastasis, such as a size greater than 2 cm in diameter or a depth of invasion greater than 2 to 4 mm. Selective neck dissection in the clinically N0 patient is beneficial when tumor is found on pathologic evaluation of the specimen; this allows for early removal of metastatic disease and accurate staging information on which to base adjuvant therapy. Unfortunately, this approach has led to unnecessary surgery in 65% to 75% of patients with early-stage OSCC. Additionally, neck dissection is associated with neurogenic shoulder dysfunction and esthetic deformity in a significant number of individuals. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is a minimally invasive technique that is currently under investigation for staging of OSCC. It offers the potential for reducing the morbidity associated with selective neck dissection.

Seaman and Powers published the first report of lymphatic mapping for cancer patients in 1955. They described the injection of breast tumors with radiolabeled colloidal gold and mapped the progression of the tracers through the regional lymphatics. Five years later, Gould et al. coined the term “sentinel node” to describe a level II cervical lymph node consistently identified during parotidectomy for malignant tumors; the status of this node guided the surgeons to complete or forego neck dissection.

The concepts of a “sentinel lymph node” and lymphatic mapping were first used to reliably and accurately predict regional cancer spread by Morton et al. in 1992. This group reported data from 223 patients with stage I cutaneous melanoma in which a vital blue dye–directed sentinel node identification and regional lymphadenectomy were performed. Lymphoscintigraphy was used in ambiguous sites. In the study, 194 sentinel nodes were identified in 237 nodal basins; only two nonsentinel nodes were the site of metastasis in specimens with a negative sentinel node (a false-negative rate of less than 1%). This established sentinel lymph node biopsy as an accurate staging procedure for early-stage cutaneous melanoma.

SLNB for cutaneous melanoma and breast cancer has become widely accepted as a less invasive staging procedure for early primary tumors. More recently, it has shown promise in accurately predicting and staging regional lymphatics in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). In 1996, Alex and Krag identified a sentinel node using gamma probe localization from a laryngeal cancer. In 1998, Koch et al. and Pittman et al. used a radioactive colloid tracer and isosulfan blue dye, respectively, to identify sentinel nodes in HNSCC, with equivocal results. One year later, Shoaib et al. combined the two modalities (radiotracer and dye) and identified the sentinel node in 15 of 16 patients with clinically negative necks with OSCC; they also accurately detected 100% of occult neck disease.

Multiple single-center pathologic validation studies on SLNB in oral cancer suggest that it is efficacious for the identification of sentinel lymph nodes, that it is capable of detecting occult metastasis, and that it accurately predicts the status of the lymphatic basins draining the primary tumor in some patients, with negative predictive values between 90% and 98%. Two consensus conferences and a meta-analysis of the existing data suggested an evolving role for SLNB in the staging of OSCC, and recommendations for pathologic processing were made. A prospective trial in six European centers that studied SLNB either alone or followed by neck dissection resulted in upstaging of 34% of the oral cancer patients and demonstrated a false-negative rate of 7.1%. The results of the ACOSOG Z0360 validation trial, recently published, showed that for T1 or T2 oral squamous cell carcinoma, SLNB with serial step sectioning (SSS) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) resulted in a negative predictive value of 96%. The authors concluded that it is reasonable to initiate clinical trials involving SLNB, with completion of neck dissection only in selected OSCC patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Current indications for SLNB include biopsy-confirmed T1 or T2 oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma of all subsites, including the tongue, floor of the mouth, retromolar trigone, buccal mucosa, alveolus/gingiva, hard palate, and lip, with clinically negative neck disease based on the physical examination and advanced imaging (e.g., contrast-enhanced computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]). SLNB can be beneficial in staging ipsilateral or bilateral necks for unilateral or midline tumors, respectively.

Limitations and Contraindications

SLNB is a minimally invasive staging technique for early cancers of the oral cavity and oropharynx with clinically negative neck disease. Patients with clinical or radiographic evidence of neck metastasis should undergo formal therapeutic neck dissection and/or definitive radiotherapy. Current contraindications to SLNB include:

- •

Lack or unavailability of a nuclear medicine facility

- •

Clinically evident neck disease

- •

History of cancer or surgery in the neck

- •

History of radiation to the neck

- •

Recent neck trauma

- •

Advanced primary tumor that requires free tissue transfer and neck dissection for vascular access

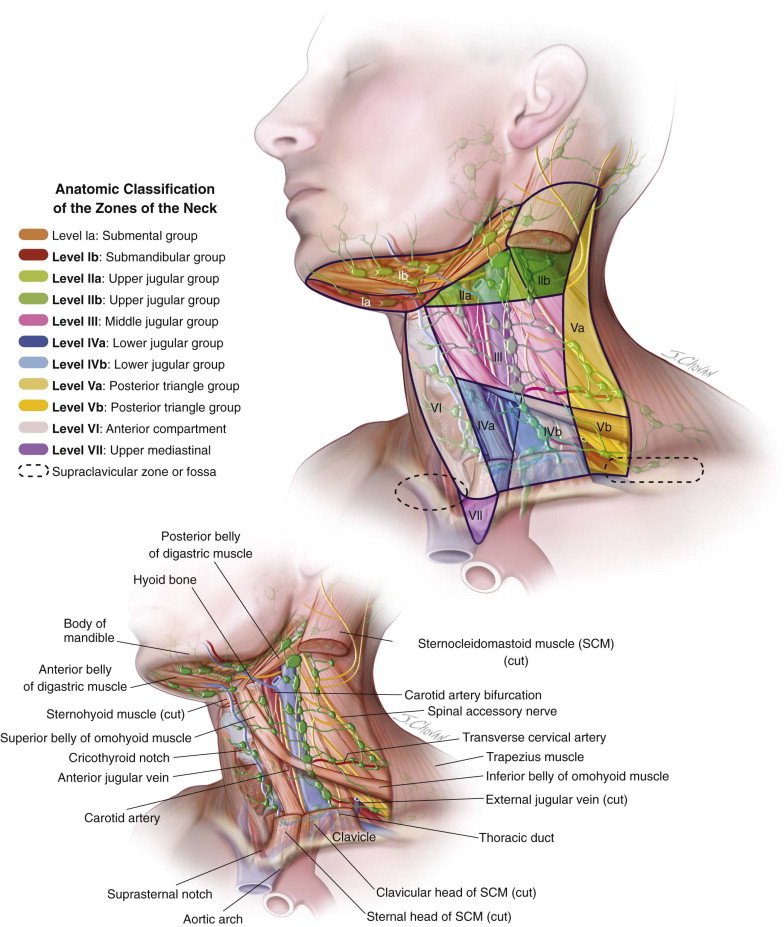

SLNB for floor of the mouth tumors is limited by the “shine-through” effect of a radiotracer and interference with evaluation of the nearby level I lymph nodes ( Figure 104-1 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses