Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Problems with the velopharyngeal mechanism can greatly affect speech production and create varying degrees of difficulty with production of key speech sounds. The patients most often affected by this problem are those with cleft palates. The pharyngeal flap procedure is the most widely used surgical treatment for velopharyngeal insufficiency or incompetence (VPI). The procedure was first described by Schoenborn in 1876. When randomly applied to patients with VPI, the superiorly based pharyngeal flap procedure is effective 80% of the time. When the flap is applied using careful preoperative objective evaluations, success rates as high as 95% to 97% have been reported. Shprintzen and Shprintzen et al. have advocated custom tailoring of the pharyngeal flap width and position based on the particular characteristics of each patient as seen on nasopharyngoscopy.

The high overall success rate and the flexibility to design the dimensions and position of the flap itself are advantages. The disadvantages of the pharyngeal flap procedure are primarily related to the possibility of severe nasal obstruction, resulting in mucus trapping and postoperative obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Inferiorly based pharyngeal flaps for management of VPI were used in the past but are rarely performed today. Previous reports have documented increased morbidity without better speech outcomes associated with inferiorly based flaps. In addition, inferiorly based flaps tend to cause downward pull on the soft palate after healing and contracture of the flap. The result may be a tethered palate with decreased ability to elevate during the formation of speech sounds.

The sphincter pharyngoplasty is another option for the surgical management of VPI. This procedure was described by Hynes in 1951 and since has been modified by a number of other authors. Augmentation of the posterior pharyngeal wall has been attempted to facilitate closure of the nasal airway. Various autogenous and alloplastic materials have been used, including local tissue, rib cartilage, injections of Teflon, silicon, Silastic, Proplast, and collagen. Improvement in speech after augmentation of the posterior pharyngeal wall is unpredictable. Difficulties with migration or extrusion of the implanted material and an increased rate of infection add to the problems of these techniques. For these reasons, pharyngeal wall implants are rarely used today.

History of the Procedure

Problems with the velopharyngeal mechanism can greatly affect speech production and create varying degrees of difficulty with production of key speech sounds. The patients most often affected by this problem are those with cleft palates. The pharyngeal flap procedure is the most widely used surgical treatment for velopharyngeal insufficiency or incompetence (VPI). The procedure was first described by Schoenborn in 1876. When randomly applied to patients with VPI, the superiorly based pharyngeal flap procedure is effective 80% of the time. When the flap is applied using careful preoperative objective evaluations, success rates as high as 95% to 97% have been reported. Shprintzen and Shprintzen et al. have advocated custom tailoring of the pharyngeal flap width and position based on the particular characteristics of each patient as seen on nasopharyngoscopy.

The high overall success rate and the flexibility to design the dimensions and position of the flap itself are advantages. The disadvantages of the pharyngeal flap procedure are primarily related to the possibility of severe nasal obstruction, resulting in mucus trapping and postoperative obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Inferiorly based pharyngeal flaps for management of VPI were used in the past but are rarely performed today. Previous reports have documented increased morbidity without better speech outcomes associated with inferiorly based flaps. In addition, inferiorly based flaps tend to cause downward pull on the soft palate after healing and contracture of the flap. The result may be a tethered palate with decreased ability to elevate during the formation of speech sounds.

The sphincter pharyngoplasty is another option for the surgical management of VPI. This procedure was described by Hynes in 1951 and since has been modified by a number of other authors. Augmentation of the posterior pharyngeal wall has been attempted to facilitate closure of the nasal airway. Various autogenous and alloplastic materials have been used, including local tissue, rib cartilage, injections of Teflon, silicon, Silastic, Proplast, and collagen. Improvement in speech after augmentation of the posterior pharyngeal wall is unpredictable. Difficulties with migration or extrusion of the implanted material and an increased rate of infection add to the problems of these techniques. For these reasons, pharyngeal wall implants are rarely used today.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

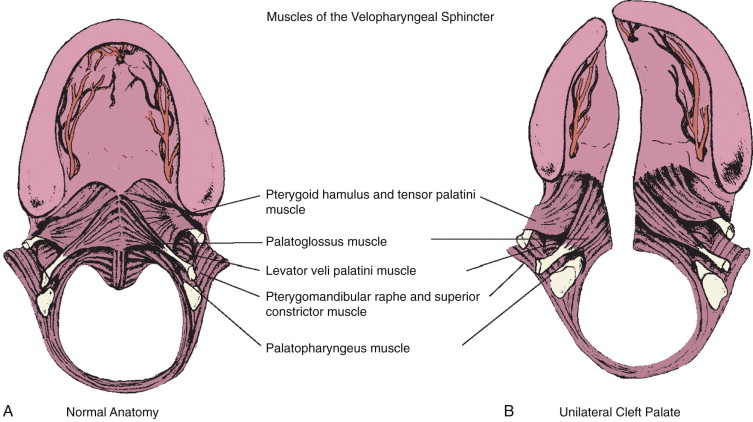

The secondary palate is composed of a hard (bony) palate anteriorly and a soft palate, or velum, posteriorly. Within the soft palate, the levator veli palatini muscle forms a dynamic sling that elevates the velum toward the posterior pharyngeal wall during the production of certain sounds. Other muscle groups within the velum, the tonsillar pillar region, and the pharyngeal walls also affect resonance quality during speech formation. The combination of the soft palate and pharyngeal wall musculature forms what is described as the velopharyngeal mechanism ( Figure 54-1, A ) . The velopharyngeal mechanism functions as a complex sphincter valve to regulate airflow between the oral and nasal cavities and create a combination of orally based and nasally based sounds. By definition, children born with a cleft palate have a malformation that dramatically affects the anatomic components of the velopharyngeal mechanism. Clefting of the secondary palate causes division of the musculature of the velum into separate muscle bellies with abnormal insertions along the posterior edge of the hard palate ( Figure 54-1, B ). The initial palatoplasty, as described earlier, is not simply carried out for closure of the palatal defect (oronasal communication) itself, but is aimed at addressing the underlying muscular anatomic deformity. During two-flap palatoplasty, care must be taken to sharply separate the levator muscle bellies off the palatal shelves, realign them, and establish continuity to create a functioning palatal-levator muscle sling. Some describe this primary repair of the palatal musculature as an intravelar veloplasty. Although this description helps to articulate the importance of addressing the levator muscle, it may confuse some clinicians by suggesting that muscle repair, or intravelar veloplasty, is a separate procedure. The degree of aggressive retropositioning of the levator musculature can vary among surgeons. Regardless of the cleft palate repair technique used (e.g., von Langenbeck, Bardach, Furlow), meticulous release of abnormal levator muscle insertions with velar muscle reconstruction must be incorporated as a critical element of the surgical procedure.

Most children who undergo successful cleft palate repair during infancy (9 to 18 months) go on to develop speech that is normal or demonstrate minor speech abnormalities that are amenable to speech therapy. In a smaller segment of this patient population, the velopharyngeal mechanism does not demonstrate normal function despite surgical closure of the palate. VPI is defined as inadequate closure of the nasopharyngeal airway port during speech production. The exact cause of VPI after “successful” cleft palate repair is a complex problem that remains difficult to define and quantify. Inadequate surgical repair of the musculature is one potential cause of VPI. The role of postsurgical scarring and its impact on muscle function and palatal motion are poorly understood. The theoretic advantages of using a Furlow double-opposing Z -plasty procedure for the initial palate repair include better realignment of the palatal muscles and lengthening of the soft palate. These benefits may be negatively balanced by a velum that demonstrates less mobility secondary to scarring associated with two separate Z -plasty incisions.

Even muscles that are appropriately realigned and reconstructed may fail to heal normally and function properly because of congenital defects having to do with their innervation. In addition, a repaired cleft palate is only one factor contributing to velopharyngeal function. Nasal airway dynamics and abnormalities related to vocal tract morphology and lateral and posterior pharyngeal wall motion may contribute to velopharyngeal dysfunction. Certainly, these other structures may also play a positive role in compensating for palatal deformity. For example, a short, scarred soft palate that does not elevate very well may be compensated for by recruitment and hypertrophy of muscular tissue within the posterior pharyngeal wall (activation of Passavant’s ridge). The audible nasal air escape that results in hypernasal speech associated with VPI is perhaps the most debilitating consequence of the cleft palate malformation. A variable number of children with VPI after palatoplasty go on to require management involving additional palatal and pharyngeal surgery. The percentage is quite variable and not universally agreed on but generally is 15% to 40% for nonsyndromic patients. Patients with known and identifiable syndromes have higher rates of VPI, but these are generally due to other contributing factors, such as cognitive status or neural innervation. Other studies claim much lower rates of VPI, but measurement and reporting are neither uniform nor validated in these published studies. Without a truly objective measure of speech in this patient population, it is difficult to know the true incidence of VPI after repair.

Left untreated, nasal air escape–related resonance problems lead to other compensatory speech abnormalities and articulation errors. The aerodynamic demands theory proposed by Warren provides the best explanation of what occurs with severe VPI. His theory states that nasal air escape due to inadequate velopharyngeal closure causes the patient to articulate pressure consonants at the level of the larynx or pharynx instead of within the oral cavity. These abnormal compensatory misarticulations further complicate problems with speech formation and reduce speech intelligibility in patients with cleft palate–related VPI.

Indications for and Timing of Surgery

After the initial cleft palate repair, periodic evaluations are critical to assess the speech and language development of each child. Typically this involves a standardized screening examination performed by a speech and language pathologist as part of a visit to the cleft palate team. For patients with VPI, more detailed studies may be indicated, including the use of videofluoroscopy and nasopharyngoscopy. Videofluoroscopic studies are used to radiographically examine the upper airway with the aid of an oral contrast material. These techniques allow dynamic testing of the velopharyngeal mechanism with views of the musculature in action. In addition, details of the upper airway anatomy, including residual palatal fistulas, can be visualized and their contribution to speech dysfunction evaluated. For a videofluoroscopy study to be of diagnostic value, it must include multiple views of the velopharyngeal mechanism. The speech pathologist should be present to verbally test the patient in the radiology suite.

Nasopharyngoscopy using a small, flexible, fiberoptic endoscope is routinely used for the evaluation of patients with VPI. Nasopharyngoscopy allows for direct visualization of the upper airway, and specifically the velopharyngeal mechanism, from the nasopharynx. This technique avoids radiation exposure associated with videofluoroscopy but requires preparation of the nose with a topical anesthetic, skillful maneuvering of the scope, and a compliant patient. Once the endoscope has been inserted, observations of palatal function, airway morphology, and pharyngeal wall motion are made while the patient is verbally tested by the speech pathologist. The opportunity for direct visualization of the velopharyngeal mechanism in action during speech formation provides information that is critical to clinical decision making related to secondary palatal surgery in cases of confirmed or suspected VPI. The pattern of closure and the characteristics of any abnormal closure patterns during certain speech sounds may help tailor treatment and tend to be valuable information to optimize speech.

Secondary palatal surgery in young children is indicated when VPI causes hypernasal speech on a consistent basis and is related to a defined anatomic problem. The timing of surgery for VPI remains controversial. Recommendations typically range from 3 to 5 years of age. In young children, obtaining enough diagnostic information to make a definitive decision regarding treatment is often difficult. In such a young age group, variables such as the child’s language and articulation development and a lack of compliance during the speech evaluation compromise the diagnostic accuracy of preoperative assessments.

By the time a child reaches 5 years of age, compliance with nasopharyngoscopy is better, and there is enough language development to allow for a more thorough perceptual speech evaluation. These factors allow for more definitive conclusions regarding the status of velopharyngeal function or dysfunction in the child with a repaired cleft palate. It is also important to note that decisions regarding the advisability of surgery for VPI are usually made after close collaboration with an experienced speech and language pathologist. The surgeon and speech pathologist should make this decision together and try to tailor the treatment to that particular child’s needs.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses