Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Mandibular fractures in children follow different patterns from those in adults. In children, 80% of mandibular fractures involve the condyle or subcondylar region (up to 50%) or the mandibular angle. Body fractures are relatively rare. Symphysis and parasymphysis fractures comprise approximately 20% of pediatric mandibular fractures. Younger children (under 6 years of age) have thick, short condylar necks that fracture less often, compared to older. Young children have highly vascular condylar heads that are susceptible to crush injuries. Treatment decisions must take into account the potential for mandibular growth and eruption of the primary and succedaneous teeth. This has been a recognized tenet of management since the 1960s. Since the advent of rigid fixation, there has been significant debate about its use in the growing mandible and also the use of resorbable materials for this purpose. The goals of treatment in children are to obtain bony union, restore occlusion, and prevent and subsequently monitor for growth disturbances.

History of the Procedure

Mandibular fractures in children follow different patterns from those in adults. In children, 80% of mandibular fractures involve the condyle or subcondylar region (up to 50%) or the mandibular angle. Body fractures are relatively rare. Symphysis and parasymphysis fractures comprise approximately 20% of pediatric mandibular fractures. Younger children (under 6 years of age) have thick, short condylar necks that fracture less often, compared to older. Young children have highly vascular condylar heads that are susceptible to crush injuries. Treatment decisions must take into account the potential for mandibular growth and eruption of the primary and succedaneous teeth. This has been a recognized tenet of management since the 1960s. Since the advent of rigid fixation, there has been significant debate about its use in the growing mandible and also the use of resorbable materials for this purpose. The goals of treatment in children are to obtain bony union, restore occlusion, and prevent and subsequently monitor for growth disturbances.

Limitations and Contraindications

The presence of significant cranial, cervical spine, thoracoabdominal, or other injuries that may reduce the likelihood of survival should be assessed first. Although management of facial fractures is an important aspect of care of the traumatized pediatric patient, assessment generally occurs as part of the secondary survey and managed after life-threatening injuries. The practitioner should suspect additional injuries in any child with a mandibular fracture. Significant force is required to fracture the pediatric mandible, given its lower modulus of elasticity and tendency to green-stick rather than fracture completely.

Clinical and radiographic examinations are required for diagnosis of pediatric mandibular fractures. The ability to elicit subjective complaints of malocclusion or inferior alveolar nerve dysfunction is limited in children, and imaging is often the best method of diagnosis. Plain films are often inadequate because they rely on cooperation from the child for accuracy. The short condyle-ramus unit in children leads to overlapping structures in panoramic radiographs, and fractures can be missed. Computed tomography (CT) is needed to delineate this area and is becoming the standard in hospital settings due to its increased accuracy compared to plain films.

As with all operative procedures in pediatric patients, precise communication between the provider and parents, in addition to age-appropriate explanations to the patient, are required for full compliance with treatment. Although it was historically believed that children could not tolerate maxillomandibular fixation (MMF), age is not a contraindication to MMF. The presence of significant medical conditions (e.g., epilepsy, coagulopathy) may be relative contraindications to a given approach (i.e., closed and open reduction, respectively).

Technique: Closed Reduction with or without Maxillomandibular Fixation

Step 1:

Overview

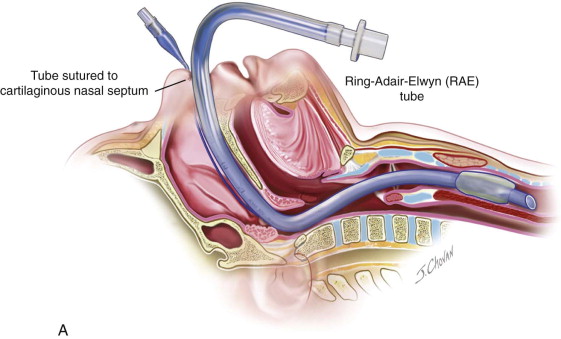

The procedure is most appropriately completed in younger children under general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation. In adolescents, local anesthesia and/or intravenous sedation may be appropriate ( Figure 70-1, A ).

Step 2:

Reduction of Fracture

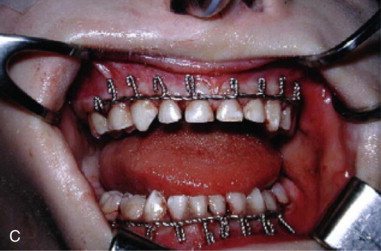

Once adequate anesthesia has been achieved, the fracture is reduced manually, based on the alignment of the mandibular dentition and occlusion. Once this has been accomplished, arch bars or equivalent should be placed.

Step 3:

Placement of Arch Bars

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses