Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

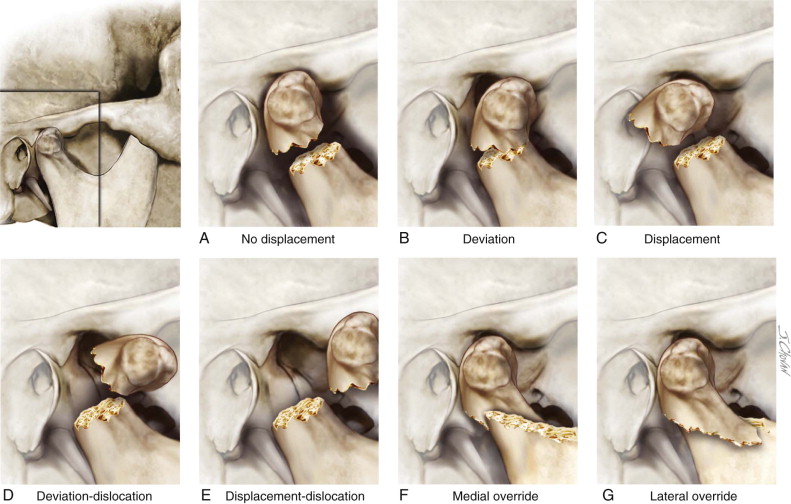

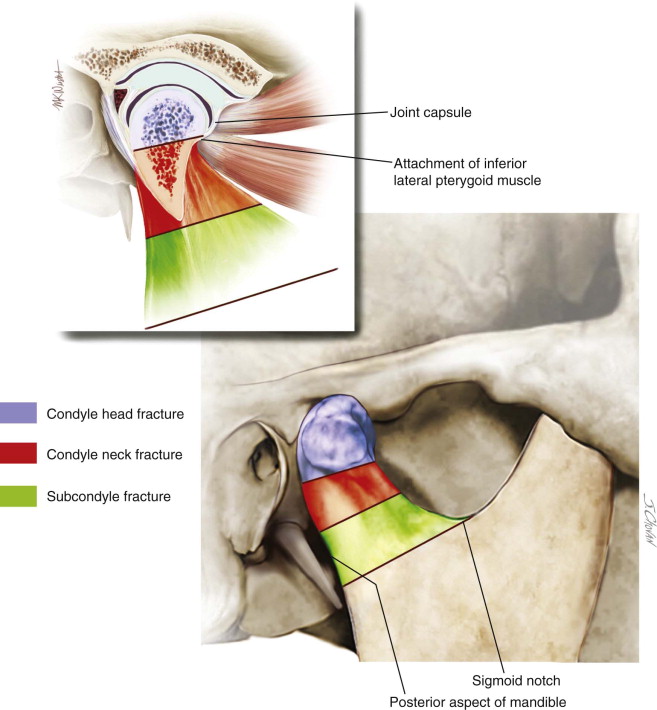

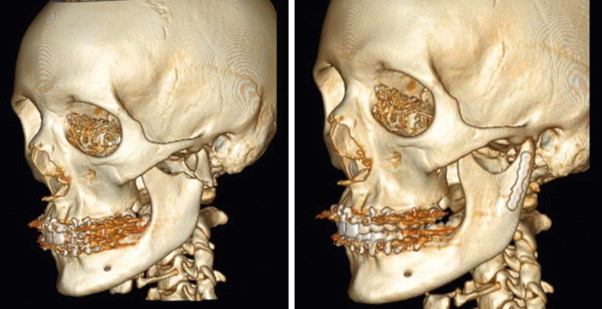

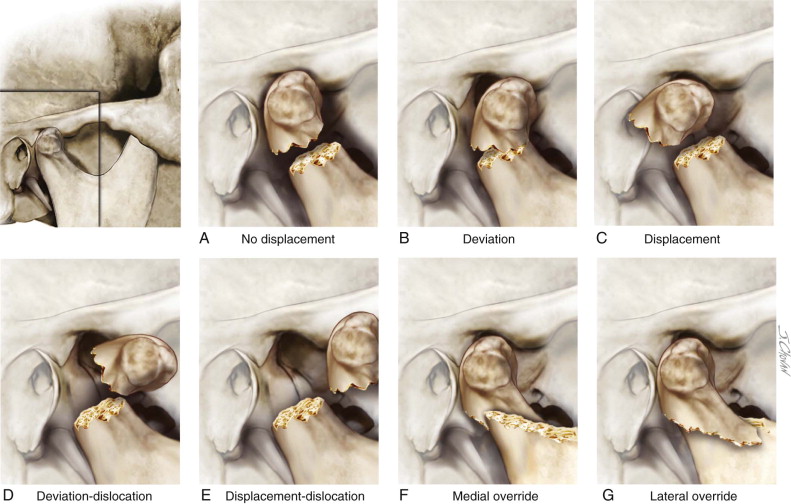

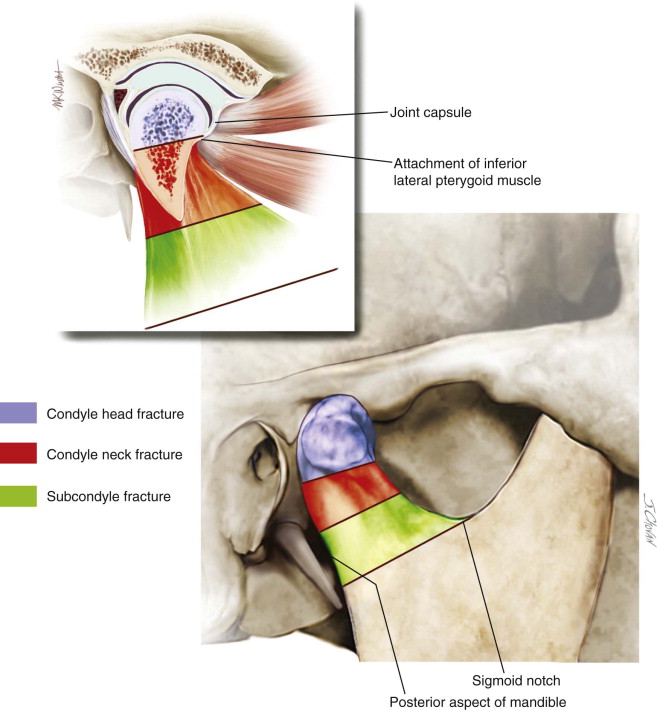

Fractures of the mandibular condyle compose 25% to 35% of all mandible fractures. Classification and management of condylar fractures is a controversial topic in maxillofacial trauma. This is due to the anatomic complexity of the condyle, the extensive attachments, and its contribution to the temporomandibular joint. Lindahl’s classification of mandibular condyle fractures is a complex but commonly used system. It is based on the level of the fracture, the amount of displacement, and the relationship of the condylar head to the fossa ( Figure 67-1 ). Lindahl classified the fractures based on the levels of the fracture: condyle head fracture, condyle neck fracture, and subcondyle fracture ( Figure 67-2 ). A condyle head fracture is located within the joint capsule; a condyle neck fracture is inferior to the joint capsule and inferior to the attachment of the lateral pterygoid muscle. A subcondyle fracture is inferior to the condyle between the sigmoid notch and the posterior aspect of the mandible. Spiessl identified six fracture types (1 to 6) that described the displacement of the fracture fragments and dislocation of the condylar head from the fossa. The classifications are: fracture with no dislocation, inferior condylar neck fracture with dislocation, superior condylar neck fracture with dislocation, inferior condylar neck fracture with luxation, superior condylar neck fracture with luxation, and intracapsular fracture.

Neff et al further classified condylar head fractures into three types. In this classification, type A is through the medial part of the condylar head; type B is through the lateral part of the condylar head; and type C is near the attachment of the lateral capsule. Bhagol et al developed a subcondylar fracture classification system based on ramus height shortening and the degree of fracture displacement. He recommended Class I (minimally displaced) be treated with conservative management. Class II (moderately displaced) can be treated with conservative or surgical management, although functional outcomes in this group were slightly better in the surgically treated group. Class III (severely displaced) fractures are treated surgically. Loukota et al recently developed a subclassification of subcondylar fractures into high condylar neck, low condylar base, and dicapitular fractures. Ellis et al further simplified condylar fractures into three groups: condylar head, neck, and base fractures.

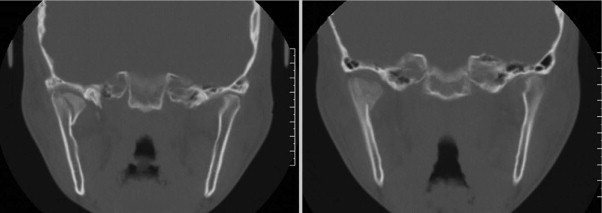

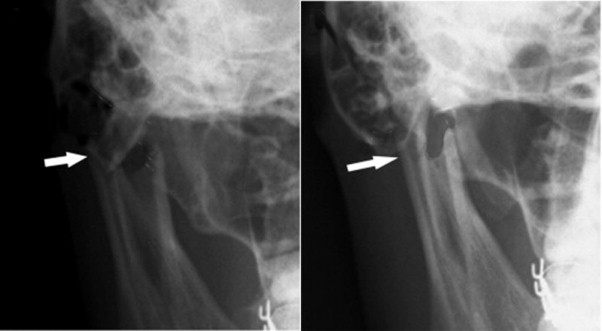

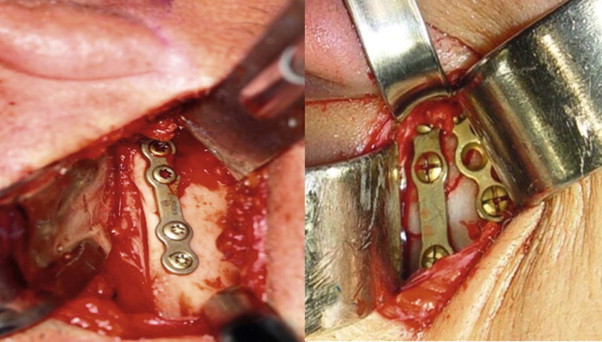

The management of condylar fractures is controversial and includes observation, closed treatment, and open reduction with or without endoscopic visualization by transfacial or intraoral approaches ( Figure 67-3 ). Studies published in the past decade are more favorable to open surgical management. The isolated intracapsular fracture is treated solely with physical therapy. Although these fractures can result in significant anatomic and radiologic changes in the appearance of the condyle itself, most patients do well if properly rehabilitated ( Figure 67-4 ). Singh et al recently published the largest blinded, randomized controlled trial comparing surgical (open) techniques with closed management; they concluded that both treatment options yield acceptable results ( Figure 67-5 ). However, the surgically treated group was superior in all objective and subjective functional parameters except occlusion ( Figure 67-6 ). A recent meta-analysis, which contained 20 studies, including four randomized controlled trials, found that surgical management was as good as or better than conservative management ( Figure 67-7 ).

The surgical approach to the condyle for open reduction and fixation is dictated by the level of the fracture, the surgeon’s experience and skill level, the degree of fracture displacement or dislocation, the patient’s desires, and the complication risk, among other factors. The retromandibular approach is the most versatile approach to the condylar head, neck, and ramus. There are two variations of this technique: transparotid and retroparotid. The transparotid technique described by Hinds with modification by Ellis provides the shortest distance with quickest access from the skin to the mandible. The branches of the facial nerve are frequently encountered; however, complications with facial nerve weakness or injury seldom occur. The retroparotid technique requires an incision that is longer and is 2 cm posterior to the ramus, thus enabling dissection to proceed deep to the parotid gland and facial nerve. The disadvantage of this approach is the dissection and the working distance between the incision and the condyle.

Wire fixation, intramedullary pins, miniplates, and rigid compressive plates have been used to stabilize these fractures. However, a single rigid miniplate or two semirigid plates are the current treatment of choice ( Figure 67-8 ).

History of the Procedure

Fractures of the mandibular condyle compose 25% to 35% of all mandible fractures. Classification and management of condylar fractures is a controversial topic in maxillofacial trauma. This is due to the anatomic complexity of the condyle, the extensive attachments, and its contribution to the temporomandibular joint. Lindahl’s classification of mandibular condyle fractures is a complex but commonly used system. It is based on the level of the fracture, the amount of displacement, and the relationship of the condylar head to the fossa ( Figure 67-1 ). Lindahl classified the fractures based on the levels of the fracture: condyle head fracture, condyle neck fracture, and subcondyle fracture ( Figure 67-2 ). A condyle head fracture is located within the joint capsule; a condyle neck fracture is inferior to the joint capsule and inferior to the attachment of the lateral pterygoid muscle. A subcondyle fracture is inferior to the condyle between the sigmoid notch and the posterior aspect of the mandible. Spiessl identified six fracture types (1 to 6) that described the displacement of the fracture fragments and dislocation of the condylar head from the fossa. The classifications are: fracture with no dislocation, inferior condylar neck fracture with dislocation, superior condylar neck fracture with dislocation, inferior condylar neck fracture with luxation, superior condylar neck fracture with luxation, and intracapsular fracture.

Neff et al further classified condylar head fractures into three types. In this classification, type A is through the medial part of the condylar head; type B is through the lateral part of the condylar head; and type C is near the attachment of the lateral capsule. Bhagol et al developed a subcondylar fracture classification system based on ramus height shortening and the degree of fracture displacement. He recommended Class I (minimally displaced) be treated with conservative management. Class II (moderately displaced) can be treated with conservative or surgical management, although functional outcomes in this group were slightly better in the surgically treated group. Class III (severely displaced) fractures are treated surgically. Loukota et al recently developed a subclassification of subcondylar fractures into high condylar neck, low condylar base, and dicapitular fractures. Ellis et al further simplified condylar fractures into three groups: condylar head, neck, and base fractures.

The management of condylar fractures is controversial and includes observation, closed treatment, and open reduction with or without endoscopic visualization by transfacial or intraoral approaches ( Figure 67-3 ). Studies published in the past decade are more favorable to open surgical management. The isolated intracapsular fracture is treated solely with physical therapy. Although these fractures can result in significant anatomic and radiologic changes in the appearance of the condyle itself, most patients do well if properly rehabilitated ( Figure 67-4 ). Singh et al recently published the largest blinded, randomized controlled trial comparing surgical (open) techniques with closed management; they concluded that both treatment options yield acceptable results ( Figure 67-5 ). However, the surgically treated group was superior in all objective and subjective functional parameters except occlusion ( Figure 67-6 ). A recent meta-analysis, which contained 20 studies, including four randomized controlled trials, found that surgical management was as good as or better than conservative management ( Figure 67-7 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses