History of the Procedure

Rhinoplasty is one of the most commonly performed procedures in facial esthetic surgery and has generated an enormous literature. From the early techniques of endonasal approaches to the sophisticated procedures of this century, there has been a progressive adoption by many surgeons of the open rhinoplasty technique via a transcolumellar approach. This open technique was described many decades ago in relation to the cleft nasal tip deformity. For rhinoplasty procedures in general, the open approach has enabled a more direct manipulation of the osteocartilaginous framework, allowing greater accuracy in resection and repositioning and grafting of the associated hard and soft tissue components for esthetic and functional improvement.

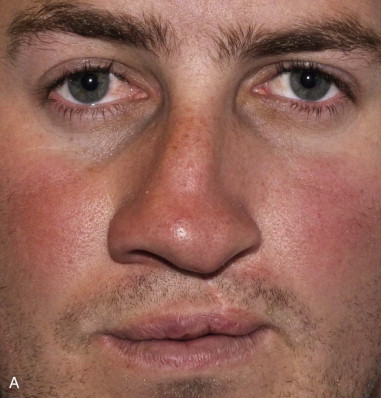

The secondary cleft nasal deformity is often the most prominent feature of an individual with a cleft anomaly, and its correction is widely regarded as one of the most challenging procedures in which to achieve consistently good results. From the earliest descriptions of the features of the cleft nose, more detailed analyses have emerged describing the components of soft tissue distortion and disproportionate bony anatomy. Correction of the nasal tip asymmetry in the patient with a cleft deformity has been advocated at the time of primary surgery to minimize future deformity, but the extent of nasal dissection at this first stage remains controversial. Some surgeons are prepared to intervene with further nasal procedures at any age if the deformity is deemed to be sufficiently severe. However, others have recommended that nasal surgery be confined to the adolescent years, when growth is almost complete. At this stage, key anatomic defects, such as displacement of the lateral crus of the alar cartilage, are stable and can be definitively repositioned and sculpted to a more normal position. An analysis of the deformity and an appreciation of the action of the muscular forces associated with the cleft explain the malposition of the tissues observed. In unilateral cases, the septum deviates to the greater segment and there is lateral displacement of the lateral crus. Although displacement of anatomic structures is well recognized, hypoplasia of tissues associated with the cleft, compounding the extent of the deformity, is less well recognized but has also been reported.

It has been suggested that early correction of the lateral crus on the cleft side minimizes the degree of deformity manifesting in adolescence. However, depending on the severity of the cleft deformity, all or some of the features seen in the primary nasal malformation may be present at the completion of growth. Definitive correction can then be undertaken, using any or a combination of accepted rhinoplasty techniques that are adapted to the specific requirements of the secondary cleft nasal deformity. Specific techniques developed for the patient with a cleft deformity are directed toward overcoming the strong anatomic soft tissue distortions caused by the congenital deformity.

History of the Procedure

Rhinoplasty is one of the most commonly performed procedures in facial esthetic surgery and has generated an enormous literature. From the early techniques of endonasal approaches to the sophisticated procedures of this century, there has been a progressive adoption by many surgeons of the open rhinoplasty technique via a transcolumellar approach. This open technique was described many decades ago in relation to the cleft nasal tip deformity. For rhinoplasty procedures in general, the open approach has enabled a more direct manipulation of the osteocartilaginous framework, allowing greater accuracy in resection and repositioning and grafting of the associated hard and soft tissue components for esthetic and functional improvement.

The secondary cleft nasal deformity is often the most prominent feature of an individual with a cleft anomaly, and its correction is widely regarded as one of the most challenging procedures in which to achieve consistently good results. From the earliest descriptions of the features of the cleft nose, more detailed analyses have emerged describing the components of soft tissue distortion and disproportionate bony anatomy. Correction of the nasal tip asymmetry in the patient with a cleft deformity has been advocated at the time of primary surgery to minimize future deformity, but the extent of nasal dissection at this first stage remains controversial. Some surgeons are prepared to intervene with further nasal procedures at any age if the deformity is deemed to be sufficiently severe. However, others have recommended that nasal surgery be confined to the adolescent years, when growth is almost complete. At this stage, key anatomic defects, such as displacement of the lateral crus of the alar cartilage, are stable and can be definitively repositioned and sculpted to a more normal position. An analysis of the deformity and an appreciation of the action of the muscular forces associated with the cleft explain the malposition of the tissues observed. In unilateral cases, the septum deviates to the greater segment and there is lateral displacement of the lateral crus. Although displacement of anatomic structures is well recognized, hypoplasia of tissues associated with the cleft, compounding the extent of the deformity, is less well recognized but has also been reported.

It has been suggested that early correction of the lateral crus on the cleft side minimizes the degree of deformity manifesting in adolescence. However, depending on the severity of the cleft deformity, all or some of the features seen in the primary nasal malformation may be present at the completion of growth. Definitive correction can then be undertaken, using any or a combination of accepted rhinoplasty techniques that are adapted to the specific requirements of the secondary cleft nasal deformity. Specific techniques developed for the patient with a cleft deformity are directed toward overcoming the strong anatomic soft tissue distortions caused by the congenital deformity.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

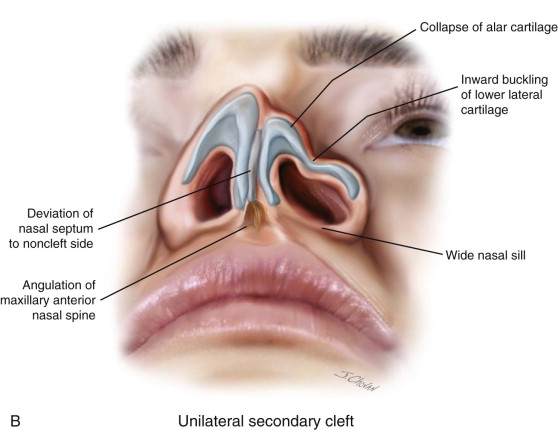

At the completion of growth, a high percentage of patients with cleft deformities have residual nasal tip asymmetry, associated nasal dorsal disproportion, and unilateral or bilateral airway obstruction due to the commonly distorted nasal septum. The degree of the deformity largely depends on the type of surgical intervention undertaken at primary surgery and/or the effects of growth on the distorted anatomy. Patients who undergo earlier correction of the cleft nasal component may have a lesser deformity at maturity due to the previous release of the lateral crus from the piriform aperture, muscle closure across the nasal floor, and repositioning of the lateral alar cartilage. Despite early attempts at correction of the malpositioned structures, the common features of the cleft nose deformity include excess width of the bony dorsum and collapse of the alar cartilage on the cleft side, with caudal displacement of the anterior edge and lateral displacement of the lateral crus that often may incorporate an inward buckling just lateral to the dome. The alar base is often flared and the nasal sill widened on the affected side ( Figure 55-1 ).

Deviation of the columella and septum to the noncleft side is due to angulation of the maxillary anterior nasal spine caused by the pull of the unopposed musculature at the margin of the cleft. The septal deflection may extend posteriorly in continuity with the vomerine septum and may result in complete posterior obstruction. The markedly deviated nasal septum is also often accompanied by a hypertrophied turbinate on the concave side and relative obstruction on the convex side due to the close proximity of the adjacent contralateral turbinate. This functional disability alone is a strong indication for a septorhinoplasty, regardless of whether esthetic concerns are an issue. The degree of depression of the piriform aperture on the cleft side is influenced by the presence of an untreated or a poorly grafted alveolar cleft where the volume of bone remaining after remodeling is much reduced. Therefore, deviation of the anteroventral cartilaginous septum to the noncleft side is a consistent finding.

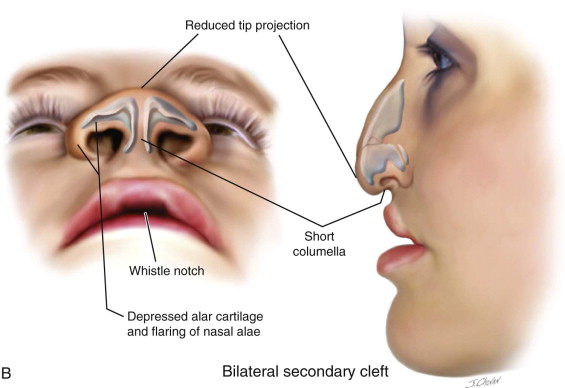

The bilateral cleft nasal deformity is more symmetric, but the nasal tip is drawn ventrally with a short columella. There is a lack of tip projection due to the depressed alar cartilages in addition to the flaring of the nasal alae, which have a more horizontal orientation ( Figure 55-2 ). A congenital soft tissue deficiency has been reported in the case of bilateral cleft deformities. Many patients with a bilateral deformity have a “whistle notch” deformity due to the deficient central element of the lip. The short columella is very difficult to lengthen esthetically, and rhinoplasty procedures aim to strengthen the nasal tip to stretch the columella and give sufficient projection. If an Abbe flap reconstruction is contemplated to lengthen the lip, then at the second stage, lip division may be undertaken in conjunction with an open rhinoplasty to address the tip deformity.

Limitations and Contraindications

The patient’s expectations regarding the degree of improvement in esthetics may be unrealistic, and counseling may be required. When only minimal or no dissection of the alar cartilages has been performed at primary surgery, the tissue planes are likely to be more easily negotiated due to minimal scarring. However, for patients who have undergone several full nasal procedures during growth, a more difficult dissection should be anticipated. For patients who have had minimal intervention at primary surgery, the lateral crus of the alar cartilage on the affected side may be tethered to the piriform aperture, and muscle may be absent under the nasal sill. Identification of these factors is important in determining how much additional dissection will be required to free and reposition the lower lateral cartilage and to remove buckles reflected in the overlying skin. In some cases, with a legacy of multiple procedures, little improvement may be gained due to the dense accumulation of scar tissue. A further major challenge is the presence of severe nostril stenosis due to a shortage of soft tissue on the cleft side. Achieving good symmetry in nostril aperture and airway may not be possible, and additional grafting techniques for lining may need to be incorporated into the treatment plan.

A considerable percentage of patients with cleft anomalies have maxillary hypoplasia. This is a combination of an intrinsic deficiency in maxillary growth and the effects of palatal scarring from the primary surgery. The degree of maxillary deficiency manifested varies from patient to patient, depending on the underlying skeletal pattern that emerges under genetic direction. The relationship of the bony foundation of the maxilla to the nasal complex has a major impact on nasal morphology. During maxillary surgery, there is an opportunity to augment the deficient piriform aperture and to reduce the often grossly deviated maxillary crest to better facilitate the subsequent nasal surgery. The alar base width is also influenced by cinch sutures that aim to return the alar bases to their correct position by reconstructing the circumoral muscular confluence to the anterior nasal spine.

Unless there are overwhelming psychological reasons for earlier treatment, nasal procedures during growth are best limited. If orthognathic surgery is contemplated at the end of growth, lip revision and rhinoplasty should be delayed for at least 6 months to enable tissue maturity. Hence, a definitive septorhinoplasty can be planned in females from around 16 years and in males from 18 years (see Figures 55-4 and 55-5 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses