Chapter 8

Short Clinical Crowns

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to review the problems associated with short clinical crowns and learn how to manage them.

Objectives

After reading this chapter the reader will appreciate the difficulties of managing teeth with short clinical crowns and understand how to overcome these difficulties.

Introduction

A difficult clinical treatment planning problem is the restoration of the short clinical crown. The principal problem associated with a short clinical crown is the retention of the restoration within the existing vertical space. Difficulties with short clinical crowns may be limited to single teeth, localised to a few teeth or be part of a more generalised problem. Management depends on the number of teeth involved and the vertical height of the existing teeth. Traditional management of teeth with short clinical crowns involves preparation of near parallel walls with slots or grooves to maximise the retention. In extreme situations, elective root treatment is advocated to gain additional retention from the root canal. Adhesive resins and techniques for the management of dentoalveolar compensation have simplified the treatment of the short clinical crown.

Single Teeth

The common causes of short clinical crowns on single teeth are:

-

trauma

-

replacement crowns

-

loss of crown height and overeruption.

Trauma

Trauma can result in substantial loss of enamel and dentine. Provided sufficient vertical space exists and a provisional restoration is placed to prevent overeruption of the opposing teeth, the complexity of the restoration depends on the amount of tooth tissue remaining and the status of the pulp. In most cases, the restoration is conventional and the management follows well established restorative techniques. In more extreme cases, the tooth may become non-vital and a root filling with or without a post retained crown is indicated to restore the tooth.

Replacement Crowns

Replacement crowns are common because of marginal caries, changes to the appearance of crowns and adjacent teeth, recession of the gingival tissues and mechanical failure. Situations may arise when a replacement crown becomes difficult once the existing crown is removed and the underlying tooth examined. For example, caries removal might produce subgingival margins or a short preparation requiring a core build-up in direct composite. An alternative is to incorporate the deficiency into the crown preparation (Fig 8-1 and Fig 8-2). The advantage of this technique is that the cement lute links the tooth to the crown directly, rather than being sandwiched between the crown and another restorative material.

Fig 8-1 This patient with fluorosis needed anterior crowns. Existing restorations were removed from the anterior teeth, but not replaced.

Fig 8-2 The completed crowns.

Loss of Crown and Overeruption of Teeth

A crown lost as a consequence of a cement failure may cause the overeruption of the opposing tooth and closure of the vertical space which accommodated the lost crown. The result is a short clinical crown in functional occlusion with the opposing tooth. This overeruption needs to be managed either orthodontically or by elective crown lengthening surgery. The former does not involve further occlusal reduction and is simpler to undertake. Apical re-positioning of the gingival margin necessitates further occlusal reduction and can lead to pulpal exposure, necessitating elective endodontic treatment.

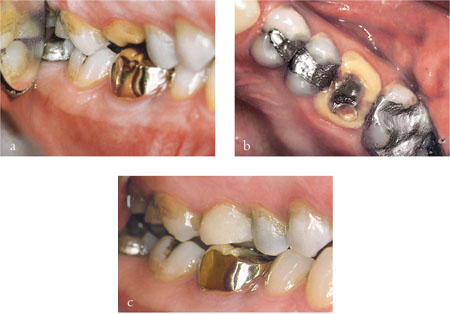

An alternative option to reverse the loss of space is to place direct composite onto the occlusal surface of the tooth, intentionally making the restoration high. For example, Fig 8-3a, 8-3b and 8-3c show what can happen when a tooth prepared for a conventional metal-ceramic crown lost its provisional crown. The prepared tooth overerupted and made contact with the opposing tooth, producing a short clinical crown. Placing a thin veneer of composite on the occlusal surface, with a thickness to match the amount of vertical space needed, reversed the overeruption within a few weeks and allowed a replacement crown to be made. If the time between crown loss and overeruption is short, then the time taken for the reversal will normally be correspondingly short.

Fig 8-3 (a–c) The upper first permanent molar lost a provisional restoration. As a result, the tooth overerupted and eventually contacted the opposing tooth, eliminating the vertical space needed for the crown. A direct composite was placed on the occlusal surface. Tooth movement returned the tooth to its original position, creating sufficient vertical space for a crown.

One problem with overerupting teeth is the simultaneous movement of the gingival margin. Reversing overeruption normally results in the movement of the gingival margin back to its original position with a good aesthetic outcome. Crown lengthening apically repositions the gingival margin and may not achieve a satisfactory result. Accepting a short crown often results in an unacceptable gingival contour on anterior teeth (Fig 8-4). This tends to be unacceptable to the patient.

Fig 8-4 Providing a crown on the upper second premolar will involve short preparations and a gingival contour which will not conform to the sagittal plane.

Surgical crown lengthening increases the vertical height of teeth, but is an unpleasant experience for the patient. The surgical repositioning of the gingival margin apically increases the crown length, but further occlusal reduction is necessary to provide space for the crown (Fig 8-5a,b).

Fig 8-5 (a,b) Surgical crown lengthening apically repositions the gingival margin and increases the length of the clinical crown. Surgery results in the exposure of interdental spaces and may cause black triangles.

When assessing the impact of the surgery it is important to note the radiographic position of the pulp. It may also be prudent to practise the crown preparation on study casts. Trial preparations aid in planning surgery. If the amount of space needed for occlusal reduction results in pulpal exposure, crown lengthening may be inappropriate. Other problems with crown lengthening surgery include dentinal sensitivity and the formation of an uneven gingival contour with unsightly black triangles between the teeth.

Multiple Crowns

Short clinical crowns on multiple teeth may be caused by uncontrolled tooth wear and this is discussed in Chapter 2 and an example shown in Fig 8-6.

Fig 8-6 Worn anterior teeth caused by erosion and attrition.

Causes of Erosion

It is often difficult to accurately diagnose the causes of erosion. Conversely, it is relatively easy to identify risk factors such as dietary acids. Since acids are common in the diet, it is often difficult to identify whether the cause of the erosion is the quantity of acid consumed, or more likely, the length of time it is present in the mouth. Holding or swilling a drink in the palatal vault prolongs erosion. Savouring citrus fruits, eating pieces of fruit over an hour or two and placing lemons against the buccal surfaces of upper anterior teeth to provide zest during sports are all known to be associated with an increased risk of erosion. Improving acid clearance by eliminating contributory dietary habits and reducing the frequency of consumption should reduce the risk of further erosion.

Gastric reflux is very common. In affected patients, the acid reflux reaches the mouth, following regurgitation, to cause erosion (Fig 8-7). Typically, tooth wear is severe when this occurs, because the low pH and titratable acidity of the refluxed gastric juice rapidly dissolves the enamel and the dentine. If tooth wear presents in patients who have reflux symptoms which interfere with their quality of life, a referral to a gastroenterologist should be considered. If the tooth wear is severe, but the symptoms of reflux disease are mild, referral to a gastroenterologist is unnecessary.

Fig 8-7 The molars on the left side are in contact, but there is an anterior open bite caused by acid erosion. Attrition can not be responsible because of the lack of anterior tooth-to-tooth contact.

The role of attrition in tooth wear is often overlooked. If bruxism is identified as the main cause of tooth wear crowns should be prescribed with caution (Fig 8-8 and Fig 8-9). Parafunctional activities cause high occlusal forces; these load small areas of dentine and enamel, producing tooth wear. The high loads placed on teeth may be damaging to restorations. Unde/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses