Chapter 7

Skull and oral anatomy

SKULL ANATOMY – OVERVIEW

The skull is the topmost part of the bony skeleton of the body, the head, and is made up of two main areas:

- Cranium – the hollow cavity that surrounds the brain

- Face – the front vertical part of the skull, containing the orbital, nasal and oral cavities and the jaws

All of the bones of the skull except the lower jaw, the mandible, are fixed to each other by immovable joints called sutures.

The base of the cranium articulates with the topmost bone of the vertebral column, the atlas, allowing nodding movements of the head.

At birth and during infancy, the bony plates making up the cranium are separated from each other by two natural membrane covered spaces called fontanelles, which allow growth of the brain without bony restriction.

By the age of 18 months the fontanelles should have closed, following the natural growth together of the bony plates making up the cranium.

ANATOMY OF THE CRANIUM

The cranium is composed of eight bones, which are separated by the cranial sutures – these are visible on a dry skull as the zig-zagged joints between the bony plates.

The bones themselves are as follows:

- Frontal bone – single plate at the front of the cranium above the eyes, forming the forehead

- Parietal bones – pair of plates forming the top and the greater area of the sides of the cranium

- Temporal bones – pair of fan-shaped plates in the temple region of the lower sides of the cranium, in front of the ears

- Occipital bone – single plate at the back and partial underside of the cranium

- Sphenoid bone – single plate forming the majority of the base of the cranium

- Ethmoid bone – single plate at the lower front of the cranium, immediately behind the nose

The skull and cranial bones are illustrated in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 Skull and cranial bones. (From Hollins, C. (2008). Levison’s Textbook for Dental Nurses, 10th edn. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.)

The main function of the cranium is to encase and protect the brain.

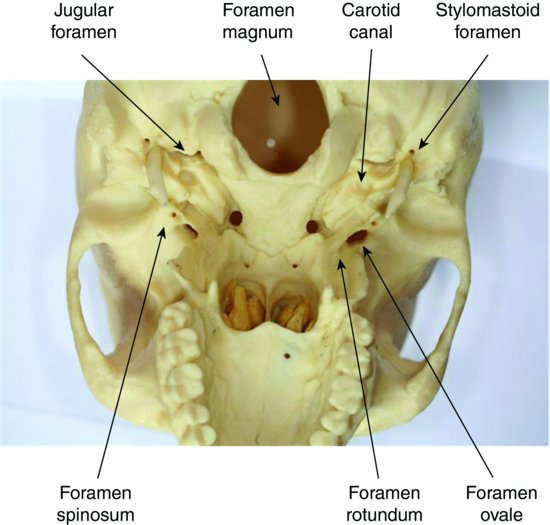

All of the sensory nerve cells running from the body to the brain, and all of the motor nerves running from the brain to the body have to pass in and out of this bony cavity, and they do so through many natural openings in the underside of the cranium, called foramina (singular – foramen).

Similarly, all of the blood vessels supplying the head and neck structures pass through these same foramina or between natural spaces between adjacent bones, called fissures.

The largest foramen of all is the foramen magnum, which opens through the occipital bone, and allows the exit of the spinal cord from the base of the brain and into the vertebral column of the spine.

Other foramina of the cranium with particular relevance to dentistry are shown in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Cranial foramina.

| Bony opening | Cranial bone | Nerves and blood vessels |

| Carotid canal | Temporal bone | Internal carotid artery |

| Foramen ovale | Sphenoid bone | Mandibular division of trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) |

| Foramen rotundum | Sphenoid bone | Trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) |

| Hypoglossal canal | Occipital bone | Hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) |

| Internal acoustic meatus (inner ear canal) | Temporal bone | Facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) Auditory nerve (cranial nerve VIII) |

| Jugular foramen | Occipital and temporal bones | Internal jugular vein Glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) Vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) Accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) |

| Stylomastoid foramen | Temporal bone | Facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) |

Some of the bony openings are listed and their positions on the underside of the cranium are shown in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2 Cranial foramina.

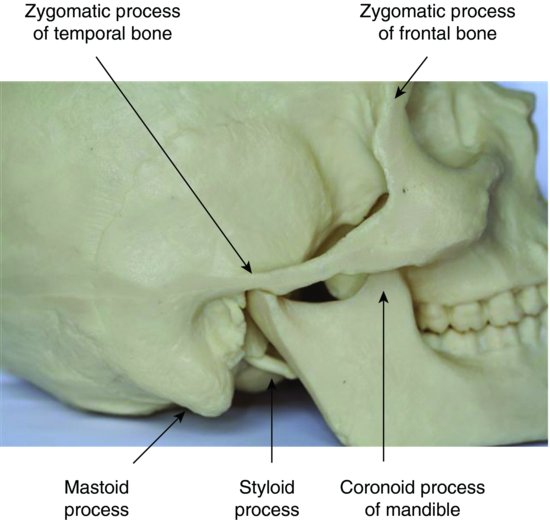

In addition to these bony openings, some cranial bones also have various projections and plates present on their outer surfaces, which serve as attachments for ligaments and muscles associated with head and jaw movements, or which form part of facial structures.

Those with particular relevance to dentistry are shown in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Cranial processes.

| Bony process | Cranial bone of origin | Associated structures |

| Mastoid process | Temporal bone | Contains air-filled spaces of the mastoid sinus and allows attachment of large neck muscle |

| Pterygoid process | Sphenoid bone | Extends into medial and lateral plates for attachment of muscles of mastication |

| Styloid process | Temporal bone | Attachment for neck muscle associated with chewing and swallowing actions |

| Zygomatic process | Frontal bone | Forms outer side of orbital cavities |

| Zygomatic process | Temporal bone | Forms portion of zygomatic arch and allows attachment of muscle of mastication |

Some of the bony processes listed and their positions on the skull are shown in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3 Anatomical processes.

Although the cranium is mainly a hollowed out cavity enclosing the brain, the head itself would be too heavy to lift by the neck muscles if the bones were solid.

Consequently, several of them contain air-filled sinuses that reduce the overall weight of the head, allowing it to be held upright and looking forwards.

The main cranial sinuses are as follows:

- Frontal sinus – in the central portion of the frontal bone, between the positions of the eyebrows

- Mastoid process – in the temporal bones, beneath the positions of the ears

- Ethmoid sinus – in the ethmoid bones, behind the nasal cavity

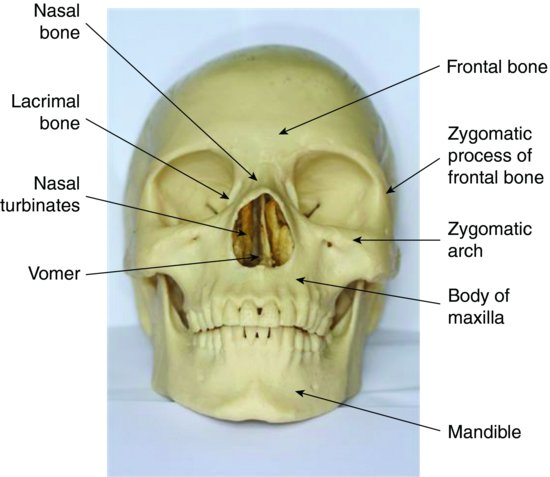

ANATOMY OF THE FACE

The face is composed of 14 bones that are all separated from each other by sutures, as in the cranium. The only exception is the mandible, forming the lower jaw, which articulates with the temporal bone at the hinged temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

The bones themselves are as follows:

- Vomer – single bone behind the nasal cavity, that articulates with cranial and other facial bones to connect the two regions of the skull together

- Lacrimal bones – pair of fragile bony plates forming the inner wall of the orbital cavities

- Nasal bones – pair of bones forming the bridge of the nose

- Nasal turbinates – pair of fragile curled bones projecting into the nasal cavity, which increase the contact of inspired air with the nasal mucosa – this aids debris removal before inhalation to the lungs, and warms the air

- Palatine bones – pair of bony plates forming the posterior section of the hard palate, and the side wall of the nasal cavity

- Zygomatic bones – pair of facial bones that articulate with the cranium posteriorly (frontal, temporal and sphenoid bones), and extend anteriorly into the zygomatic arch (cheek bone) to articulate with the maxilla

- Maxilla – pair of bones forming the upper jaw, the lower border of the orbital cavities, the base of the nose and the anterior portion of the hard palate

- Mandible – single horseshoe-shaped bone forming the lower jaw, with its posterior vertical bony struts articulating with the cranium at the TMJ

The skull and facial bones are shown in Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.4 Facial bones.

ORAL ANATOMY

The facial bones making up the oral cavity and its associated structures are of the utmost importance to all dental care professionals (DCPs). The bones will each be discussed in detail, with their associated structures covered later in this chapter.

The maxilla and palatine bones

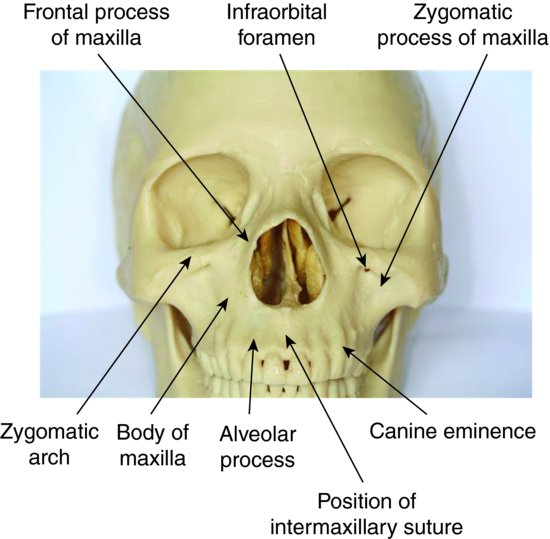

The maxilla effectively forms the middle-third of the face, and as with various cranial bones, it has several foramina and bony projections that are dentally relevant.

The two maxilla bones join together in the centreline of the face, at the intermaxillary suture, and the inferior portion of these two sections form the horseshoe-shaped alveolar process.

It is within this process that the upper teeth form in the embryo, and later erupt as the primary then secondary dentition.

Within each half of the main body of the maxilla are the large air-filled sinuses called the maxillary antra (singular antrum), and the roots of the upper posterior teeth tend to be in close or intimate contact with them.

Inflammation of these air spaces (sinusitis) due to a respiratory infection often mimics dental pain in these teeth, or conversely a dental infection can be mistaken for sinusitis.

The main anatomical landmark of the maxilla from an anterior view is the infraorbital foramen.

This natural bony opening allows the passage of the two nerves supplying sensation to the anterior upper teeth, and their surrounding soft tissues.

Some areas and protuberances of the maxilla are also the origins of various muscles of facial expression.

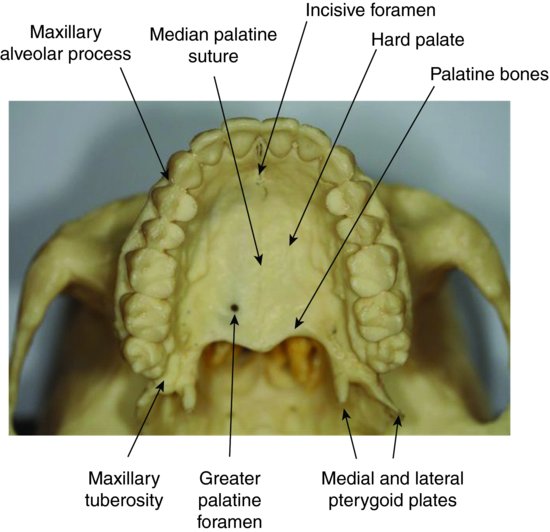

The main landmarks of the maxilla from an inferior view are those of the maxillary hard palate and the alveolar process. It is here that the palatine bones are also of relevance.

The alveolar process exists purely to hold the upper teeth in situ – when the teeth are lost, the bone gradually resorbs away and the height of the process (and therefore the face) is lost permanently, unless restored by the provision of dental treatment (dentures, implants, etc.)

The palatine process of the maxilla forms the front section of the hard palate, and is fused in the midline at the median palatine suture. The teeth are arranged from the midline backwards on each side of the alveolar process, running from the two central incisors to the third molars.

Just palatal to the central incisors is the incisive foramen, where the nasopalatine nerve emerges and supplies sensation to the palatal soft tissue covering of this area.

Posterior to the third molars is a bony protuberance called the maxillary tuberosity, which is the very end portion of the alveolar process. It is pierced by several foramina, which allow the entry of the sensory nerve supplying the majority of the molar teeth and their buccal soft tissues.

Occasionally, a nodular enlargement of the hard palate is present, and is a benign overgrowth of bony tissue called a palatal torus.

The most posterior section of the hard palate is formed by the palatine bones, and with the palatine process of the maxilla they form not only the roof of the mouth, but also the floor of the nose.

The palatine bones have two foramina present, to allow entry of the sensory nerves supplying the posterior palatal soft tissues – (1) the greater palatine foramen and (2) the lesser palatine foramen.

The various anatomical landmarks of the maxilla and palatine bones are illustrated in Figures 7.5 and 7.6.

Figure 7.5 Maxilla – anatomical landmarks.

Figure 7.6 Palate – anatomical landmarks.

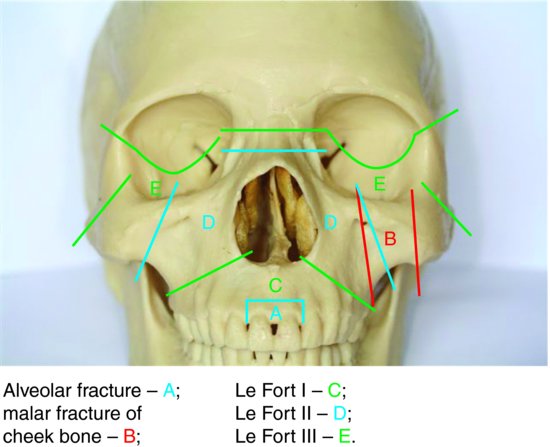

Fractures of the maxilla

From time to time, the DCP may come into contact with patients who have experienced trauma to the head and neck region. This is particularly true of those working in a maxillofacial hospital department, where the management of facial trauma is one of this unit’s many specialities.

Fractures of the middle-third of the face are a relatively frequent occurrence following horizontal trauma to the region, and often occur following events such as a car crash, a serious fall or a fight.

Conveniently, they have been classified into five categories ranging from the least to the most serious, as follows:

- Alveolar fracture – involving the anterior maxillary alveolus following a blow, or the maxillary tuberosity during tooth extraction in this region

- Malar fracture – involving the zygomatic arch and the surrounding bones, resulting in a fractured ‘cheek bone’

- Le Fort I fracture – involving the separation of the palate and maxillary alveolus from the rest of the maxilla, so effectively the whole upper jaw becomes detached from the rest of the face

- Le Fort II fracture – involving the maxillary antrum, the nose and the base of the eye sockets, so that a pyramidal central section of the face is involved

- Le Fort III fracture – involving a higher fracture line through the eye sockets and the ethmoid bone behind the nose, so effectively the whole of the face becomes detached from the cranium

The Le Fort III is the most serious fracture, as the damage through the ethmoid bone effectively opens the cranium and exposes the brain to the atmosphere. The level of damage and bone displacement experienced in any maxillary fracture will depend on the force of the trauma that caused it.

The maxillary fractures are illustrated in Figure 7.7.

Figure 7.7 Maxillary fractures. A, Alveolar fracture; B, malar fracture of cheek bone; C, Le Fort I; D, Le Fort II; E, Le Fort III.

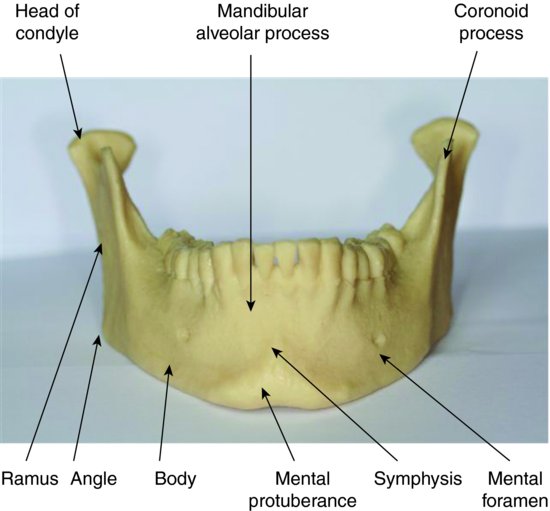

The mandible

The mandible is the single, horseshoe-shaped bone that forms the lower jaw, and is the only moveable bone of the skull.

Its front horizontal portion extends into the alveolar process, which holds the lower teeth in situ, while its two posterior vertical struts allow articulation with the temporal bone at the TMJ and allows the insertion at various points for the muscles of mastication.

Looking at the mandible from an anterior view, the following anatomical landmarks are visible:

- Mental symphysis – the fused midline point of the two halves of the mandibular processes, as they formed in the embryo

- Mental protuberance – the most anterior point of the bone, forming the chin

- Mental foramen – bony opening located between the roots of the lower premolar teeth, allowing entry of the sensory nerve supplying the anterior teeth to the second premolar, and their buccal and labial soft tissues

- Body of mandible – the base of bone that supports the full length of the lower alveolar process

Figure 7.8 shows these points.

Figure 7.8 Mandible – anterior anatomical landmarks.

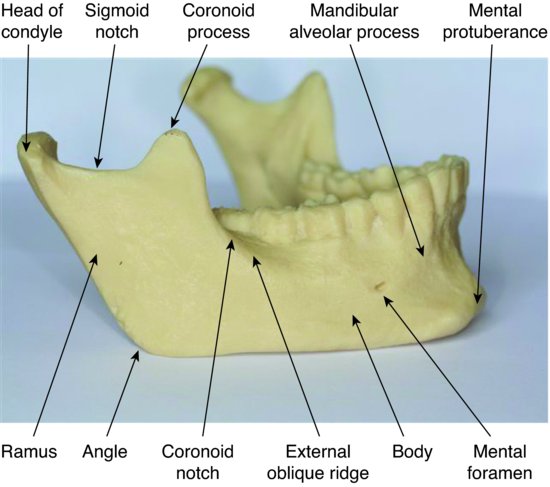

Looking at the mandible from a lateral view, the following additional anatomical landmarks are visible:

- Angle of mandible – the corner of bone where the horizontal section turns upwards to form the vertical bony strut of the mandible

- Ramus of mandible – the vertical bony strut of the mandible, and the area of insertion of a muscle of mastication

- Head of condyle – the articulation point of the mandible with the temporal bone, at the TMJ, and the point of insertion of some muscles of mastication

- Coronoid process – the front bony projection of the ramus, and a point of insertion of a muscle of mastication

- Sigmoid notch – the dipped area between the condyle and the coronoid process, at the top of the ramus

- Coronoid notch – the concave anterior surface of the ramus, as it slopes to join the body of the mandible

- External oblique line – the crest of bone at the point where the ramus and the body join together, at the base of the coronoid notch, and the point where the long buccal nerve crosses from the lateral surface of the body to the medial surface, carrying sensory nerves from the buccal soft tissues of the lower molar teeth

Figure 7.9 shows these points.

Figure 7.9 Mandible – lateral anatomical landmarks.

Looking at the mandible from a medial view, the following anatomical landmarks are visible:

- Genial tubercles – bony projections around the midline point of the medial surface of the body, and the point of insertion of various of the suprahyoid muscles

- Mylohyoid ridge – bony line running horizontally along the medial surface of the body, and the point of attachment of the mylohyoid muscle that forms the floor of the mouth

- Sublingual fossa – shallow depression above the mylohyoid ridge anteriorly, where the sublingual salivary gland sits

- Submandibular fossa – shallow depression below the mylohyoid ridge posteriorly, where the submandibular salivary gland sits

- Retromolar triangle – roughened posterior end of the alveolar process, posterior to the third molar, where a thickened soft tissue covering />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses