Chapter 1

Introduction

Aim

To familiarise the reader with planning indirect restorations, taking into consideration the importance of previous dental history. The reasons for placing indirect restorations are reappraised.

Outcome

On reading this chapter the reader will better understand the importance of prevention and maintaining pulp and periodontal health in the provision of successful indirect restorations.

Introduction

To the reader, it may seem strange that a text on successful indirect restorations should begin with a chapter discussing failures. But in terms of success, it is probably the most important subject as many indirect restorations are replacement restorations. The restorative cycle, once established, will continue unless lessons are learnt from failure events. This chapter will consider the:

-

failure of direct and indirect restorations

-

maintenance of pulp health

-

importance of periodontal health

-

importance of pulp vitality.

Why Indirect Restorations?

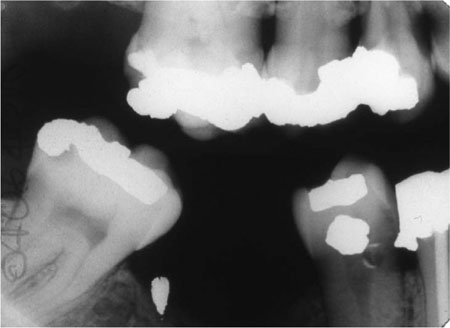

Most indirect restorations are placed to restore the contour, function and appearance of teeth previously restored with plastic restorations. In restoring broken down or damaged teeth with plastic restorations, it is sometimes difficult to achieve appropriate contact areas (Fig 1-1) and occlusal form (Fig 1-2). Indirect restorations such as crowns, onlays and inlays enable the contact areas and the occlusal form to be controlled in the laboratory. The majority of extensive restorations are placed because of primary caries, or caries adjacent to existing restorations. Others will be placed following a fracture of tooth tissue, classically a cusp fracture associated with an occlusoproximal restoration (Fig 1-3). Relatively few extensive restorations are placed as a consequence of trauma.

Fig 1-1 Bitewing radiograph showing a ledge on the amalgam restoration in the LR4. This occurred as the LR4 has an extensive defect, making it difficult to develop a tight contact area while keeping the matrix band adapted cervically.

Fig 1-2 Given the extent of this cavity, it is difficult to place an amalgam restoration with adequate occlusal contour.

Fig 1-3 The MOD restoration in this lower molar tooth, although not large, has weakened the tooth and the lingual cusp has fractured.

Why do Indirect Restorations Fail?

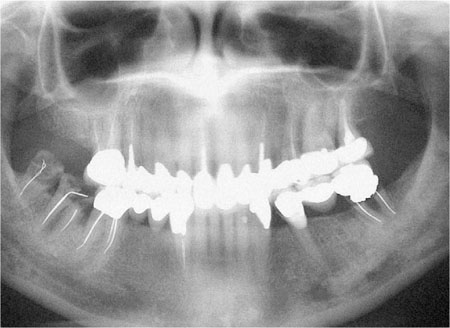

Studies on the failure of indirect restorations indicate that the commonest cause of failure is secondary caries as diagnosed clinically. Other causes include various forms of mechanical breakdown and failure, together with unacceptable appearance and endodontic and periodontic complications.

Dental Caries

Caries remains the most important disease that affects teeth. It is responsible for most directly placed restorations and their subsequent replacements. Ultimately, when direct restorations are contraindicated, indirect restorations are required, but typically these will not be permanent and will fail because of caries. This is ironic given that dental caries is a preventable disease.

Failures such as those illustrated in Fig 1-4 are preventable. It is important that we learn from such failures, by ensuring that operative dentistry is preventively driven.

Fig 1-4 Dental panoramic tomogram of a patient with an extensively restored dentition; including multiple indirect restorations. Failure of many of the restorations has been caused by caries, some have been lost (LR7 and 8), and some have been repaired (LL5).

Before placing indirect restorations, it is important that the patient’s caries risk is assessed. Only patients with a low caries risk should be prescribed indirect restorations. Some of the more important caries risk factors are included in Table 1-1.

| Low caries risk | High caries risk |

| Minimally restored dentition | Heavily restored dentition |

| No history of replacement restorations | History of frequent restoration and re-restoration |

| Good oral hygiene | Poor oral hygiene |

| Exposure to topical fluoride in water, toothpaste or mouthwash | No exposure to topical fluoride |

| Diet: low frequency of sugar intake | Diet: frequent consumption of sugar |

| High socio-economic status | Low socio-economic status |

| No new carious lesions | Presence of new carious lesions |

Treatment Planning – Stabilisation and Prevention

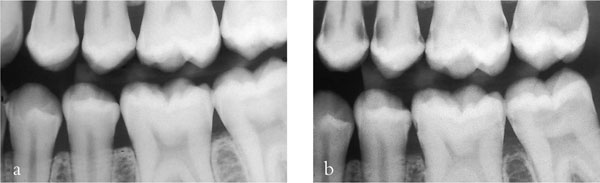

For a patient with new and secondary caries (Fig 1-5a,b) it is important that treatment is carried out in phases. The first phase should address pain and other immediate problems. Thereafter, care should be aimed at prevention. This stage of treatment should include stabilisation of the lesions and protection with temporary and transitional restorations. This is necessary to ensure that extensive lesions do not progress during the preventive phase of treatment. It also allows a stepwise approach to caries removal.

Fig 1-5 (a,b) A left bitewing radiograph of an 18-year-old patient (a), and four years later (b). This demonstrates that caries risk can change and the dentist should always be vigilant and continually assess risk. This patient’s initial treatment should be pain relief, followed by a stabilisation phase and prevention. Indirect restorations should not be considered until successful prevention has been instituted and caries risk has been controlled.

Stepwise Excavation

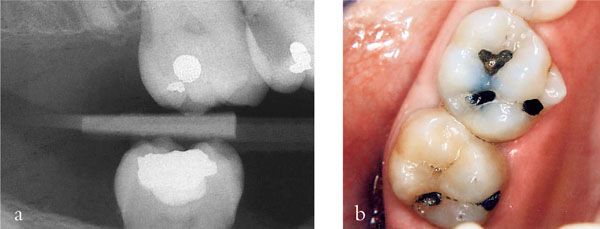

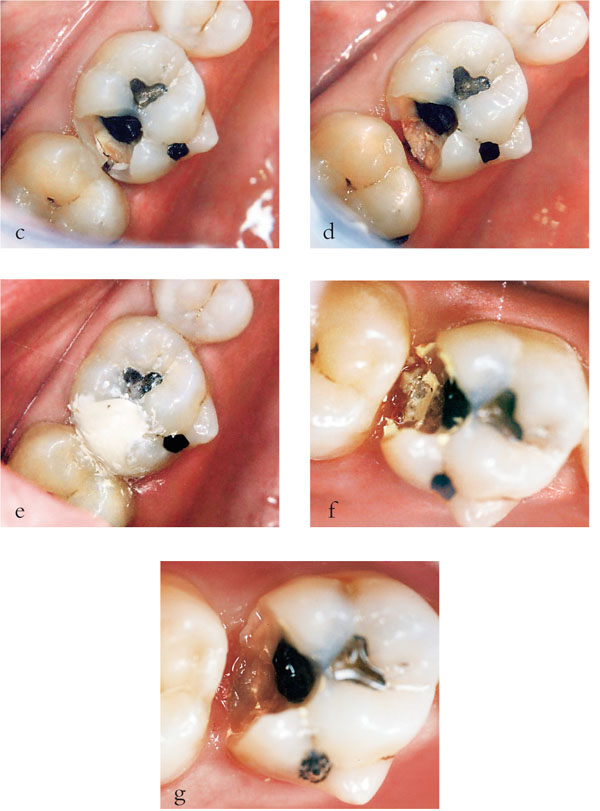

In the tooth of a young patient with a relatively large pulp and a deep carious cavity, the risk of pulpal exposure during tooth preparation is high (Fig 1-6a–g). To avoid this, a stepwise approach to caries removal should be adopted, providing there are no signs or symptoms of pulpal pathology. Assessment should include a vitality or sensitivity test and a periapical radiograph of the tooth to ascertain if periradicular pathology is present.

Fig 1-6 (a,b) A radiograph (a) and clinical appearance (b) of an extensive carious lesion on the distal aspect of the UR6 of a young teenage patient. In such a situation complete caries removal in one visit risks exposing the pulp. Stepwise excavation reduces this risk.

Fig 1-6 (c–g) In this procedure, access to the caries was gained (c) at the first appointment and peripheral caries removed leaving soft carious dentine pulpally (d). A provisional restoration was placed, using a polycarboxylate cement (e) and then left for 6 to 12 months. When the restoration was removed (f) and pulpal caries excavated no pulpal exposure occurred (g) (Series of images courtesy of Dr Nicola Innes).

During the initial stabilisation phase of treatment, access to carious dentine should be gained and peripheral caries at the enamel-dentine junction removed. This leaves soft carious dentine over the pulp, some of which can be excavated. This is then covered with a setting calcium hydroxide lining material and the tooth restored with a composite, glass-ionomer or polycarboxylate cement provisional restoration. This provisional restoration should be left for six to twelve months, during which time bacteria within the lesion will become less metabolically active and reduce in number. This is because the intraoral source of sugar substrate has been blocked by the restoration, assuming a good peripheral seal. As the bacteria become less active, the lesion activity slows and may even stop, allowing time for pulp-dentine complex reactions to occur, in particular tubular sclerosis and reactionary dentine formation. When the six to twelve months has elapsed, reentry into the lesion allows further caries removal with a significantly reduced risk of pulpal exposure. This second stage of caries removal is best carried out when the patient is complying with dietary advice, and oral hygiene instruction has been shown to be satisfactory.

Caries Prevention

The preventive aspect of treatment should include disclosing of the teeth and oral hygiene instruction (Fig 1-7a,b). Plaque scores may be useful to demonstrate problem areas to the patient and to mo/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses