Along with understanding the technical details of a specific facial surgical procedure, proper access through the skin or mucosa must be obtained. Access provides critical exposure of the injury site. Proper exposure is needed to accomplish the contemporary techniques of rigid fixation, placement of bone grafts or biomaterials, and alteration of regional bony or soft tissue anatomy. It can be argued that a thorough understanding of the various methods of contemporary surgical access has permitted many of these advances in facial reconstructive surgery to be realized.

In traumatic injuries, a laceration often provides the access to complete the necessary repair of underlying facial structures. More commonly, however, additional facial or intraoral incisions are needed. In secondary reconstructions, the use of old lacerations or new incisions is required. Either approach adds scar burden and potential associated morbidity, which in the facial area may be as potentially deforming or visually noticeable as the original injury. It is therefore important that the surgical approach and its anatomical and technical aspects be understood and well executed. In facial reconstruction, getting there often is far more difficult than executing the procedure once there.

Many areas of the facial skeleton can be accessed by an intraoral approach, and it should be the first choice. Areas not accessed through the mouth can usually be reached by means of a coronal incision that is made within the hair. Both approaches minimize the risk of visible scars. Isolated periorbital fractures can be accessed by a transconjunctival approach, and virtually all common zygomatic fracture sites can be visualized with a lateral canthopexy.

Principles

The face is composed of many intricate, delicate, and vital structures from the scalp to the neck. Rearranging and repairing many of these facial components is often not difficult, but exposing and finding them without producing additional morbidity can be. Unlike most surgical disciplines in which a direct cut-down to the defect site is usually done, facial surgery often requires remote incisions with great emphasis on their healed esthetic result. The appearance of the incisional scar or revised laceration can add or detract from the facial result as much as the original traumatic problem.

Three factors distinguish facial access from that in the remainder of the body. First, the prominent location and social importance of the face mandates that incisions be placed in locations that are as inconspicuous as possible. Second, the presence of peripheral nerves makes the location of the incisions and the dissection around them critically important. Loss of sensory input and, more importantly, weakness or loss of facial movement can be devastating for many patients and difficult to correct secondarily. Third, the compact nature of facial structures exposes structures in the path of dissection to injury, especially as the incision is located more remotely from the defect site. Complete knowledge of facial muscles, nerves, tendons, bones, and dental anatomy is important to avoid injuries. The intraoral approach should be used whenever possible to avoid skin incisions.

Incision Placement

Relaxed Skin Tension Lines

The concept of relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) is obvious in the older face, and these lines of minimal tension are good choices for incision placement because they heal with less chance of scar hypertrophy and may be less noticeable due to decreased skin shadowing. In the younger face and in most cases of surgical access, this concept has less utility than is often perceived. RSTLs are of most value in scar revision and reconstruction of local defects due to resection of skin cancer. In most cases of facial access, no surgeon would think of using any conspicuous skin area for incision placement. The first principle is to use a remote incision that lies in the nearest hidden skin crease. This creates a list of 14 basic facial incisions, including 1 coronal, 4 periorbital (upper eyelid crease, supraorbital, lower eyelid subciliary, lower eyelid transconjunctival), 5 cervicofacial (high cervical, submental, retromandibular, rhytidectomy, preauricular), 2 transoral (maxillary and mandibular vestibular), and 2 nasal (endonasal, external open) incisions.

Short Versus Long Incisions

In theory, a shorter incision results in less scar burden. Many surgeons therefore limit the incisional length, often at the expense of adequate exposure. Because the skin can stretch and slide over the surface of deeper structures, a short incision may be capable of moving a considerable distance, permitting the necessary manipulation of the underlying structures. In a limited number of facial procedures (e.g., repair of zygomatic arch fractures, endoscopic brow lift, subcondylar mandibular fracture repair), the short incision can serve as a remote portal for insertion of an endoscope or other instrument.

On a practical basis, the use of remote skin creases permits their full length to be used without excessive scar formation because the crease is already hidden. A longer incision is permitted because there is no disadvantage to using the full crease as long as the surgeon does not extend the incision beyond the anatomical boundary of the skin crease. For example, the full length of the preauricular incision can be used from the temporal hairline to the bottom of the earlobe, or a subciliary incision can be used from the medial punctum to the lateral canthal crease, as long as it does not extend beyond the lateral orbital rim.

Cold Versus Hot Cutting

The use of “cold steel” (scalpel) causes the least skin injury, with only sharp cutting of the epidermal and dermal surfaces. Bleeding of the dermal edges may prompt cauterization of some of the edges, increasing the potential for scar formation. This temptation can be avoided by the use of preincisional infiltration with a local anesthetic containing epinephrine. High concentrations work best, and 1 : 100,000 epinephrine solutions work very well, provided that the surgeon waits the obligatory 7 to 10 minutes for maximal vasoconstrictive effect. Not all skin edges need to be immediately cauterized, because most bleeding stops with some pressure and time.

Despite these basic steps, it remains appealing to use a thermal instrument to cut the skin and for subcutaneous cutting because of the immediate hemostatic effect. Traditionally, the use of cautery was associated with significant burning of skin edges because of the width of the blade and the energies used. Contemporary fine-tip needle cautery (e.g., Colorado needle, Colorado Biomedical, Evergreen, CO) uses better metals and low energies and makes it possible to significantly reduce the zone of the thermal injury on the skin edges. It is particularly useful for periorbital and preauricular incisions without any increase in adverse scarring. It should not be used in hair-bearing areas due to follicular injury and hair loss immediately adjacent to the incision. Hot cutting should never be used in the scalp, because it inevitably results in a wider, more noticeable scar due to traumatic alopecia along the incision line.

Incision Placement

Relaxed Skin Tension Lines

The concept of relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) is obvious in the older face, and these lines of minimal tension are good choices for incision placement because they heal with less chance of scar hypertrophy and may be less noticeable due to decreased skin shadowing. In the younger face and in most cases of surgical access, this concept has less utility than is often perceived. RSTLs are of most value in scar revision and reconstruction of local defects due to resection of skin cancer. In most cases of facial access, no surgeon would think of using any conspicuous skin area for incision placement. The first principle is to use a remote incision that lies in the nearest hidden skin crease. This creates a list of 14 basic facial incisions, including 1 coronal, 4 periorbital (upper eyelid crease, supraorbital, lower eyelid subciliary, lower eyelid transconjunctival), 5 cervicofacial (high cervical, submental, retromandibular, rhytidectomy, preauricular), 2 transoral (maxillary and mandibular vestibular), and 2 nasal (endonasal, external open) incisions.

Short Versus Long Incisions

In theory, a shorter incision results in less scar burden. Many surgeons therefore limit the incisional length, often at the expense of adequate exposure. Because the skin can stretch and slide over the surface of deeper structures, a short incision may be capable of moving a considerable distance, permitting the necessary manipulation of the underlying structures. In a limited number of facial procedures (e.g., repair of zygomatic arch fractures, endoscopic brow lift, subcondylar mandibular fracture repair), the short incision can serve as a remote portal for insertion of an endoscope or other instrument.

On a practical basis, the use of remote skin creases permits their full length to be used without excessive scar formation because the crease is already hidden. A longer incision is permitted because there is no disadvantage to using the full crease as long as the surgeon does not extend the incision beyond the anatomical boundary of the skin crease. For example, the full length of the preauricular incision can be used from the temporal hairline to the bottom of the earlobe, or a subciliary incision can be used from the medial punctum to the lateral canthal crease, as long as it does not extend beyond the lateral orbital rim.

Cold Versus Hot Cutting

The use of “cold steel” (scalpel) causes the least skin injury, with only sharp cutting of the epidermal and dermal surfaces. Bleeding of the dermal edges may prompt cauterization of some of the edges, increasing the potential for scar formation. This temptation can be avoided by the use of preincisional infiltration with a local anesthetic containing epinephrine. High concentrations work best, and 1 : 100,000 epinephrine solutions work very well, provided that the surgeon waits the obligatory 7 to 10 minutes for maximal vasoconstrictive effect. Not all skin edges need to be immediately cauterized, because most bleeding stops with some pressure and time.

Despite these basic steps, it remains appealing to use a thermal instrument to cut the skin and for subcutaneous cutting because of the immediate hemostatic effect. Traditionally, the use of cautery was associated with significant burning of skin edges because of the width of the blade and the energies used. Contemporary fine-tip needle cautery (e.g., Colorado needle, Colorado Biomedical, Evergreen, CO) uses better metals and low energies and makes it possible to significantly reduce the zone of the thermal injury on the skin edges. It is particularly useful for periorbital and preauricular incisions without any increase in adverse scarring. It should not be used in hair-bearing areas due to follicular injury and hair loss immediately adjacent to the incision. Hot cutting should never be used in the scalp, because it inevitably results in a wider, more noticeable scar due to traumatic alopecia along the incision line.

Coronal Access

An incision in the hairline between the temporal regions provides unparalleled exposure of the upper craniofacial skeleton and much of the orbitozygomatic region. In trauma cases, it is mainly used for fractures of the frontal bone and sinus or the naso-orbital ethmoid region and for Le Fort II and III patterns. In exceptional cases, complex fractures of the zygomatic arch may justify the use of coronal access. Its major advantages include the relative simplicity of execution, the negligible rate of complications, and the hidden location of the scar within the hairline.

Technical Points

- •

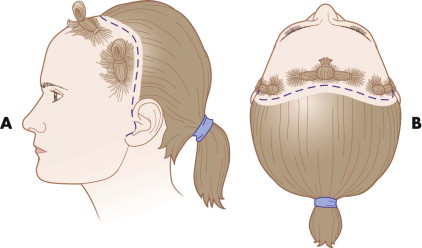

The location of the incision in female and non-alopecic male patients is 3 to 4 cm behind the frontal and temporal hairline. In balding men, more of a W -shaped pattern is chosen across the frontal component in anticipation of further recession. In the completely bald patient, the incision is made as if there were hair. It is remarkable how well bald scalp skin heals with minimal scarring ( Fig. 9-1 ).

FIGURE 9-1 Location of a coronal incision 3 to 4 cm behind the frontal hairline. - •

The ability to turn the scalp flap and attain the desired skeletal exposure depends on the inferior extent of the incisions in the temporal and auricular areas. The inferior extent of the incision can run in the preauricular or postauricular areas without compromising anterior exposure. When placing the incision in the preauricular area, retrotragal positioning is used to further hide the scar (see Fig. 9-1 ).

- •

Shaving of the incision site is optional. Shaving the hair offers no significant improvement on postoperative wound infections. It does help speed closure and is more comfortable for the patient during suture removal; ideally, it should be a narrow-strip shave.

- •

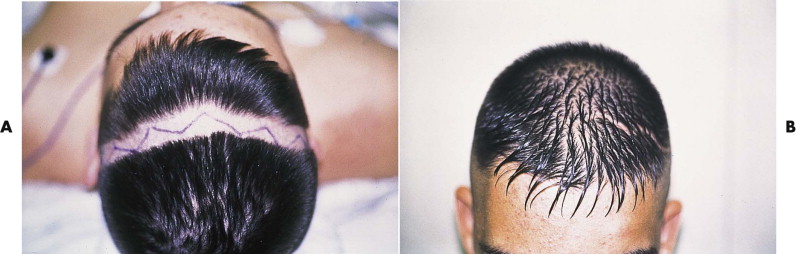

A large, running W -plasty or zigzag pattern hides the scar better by intermingling the hair pattern around the scar ( Figs. 9-2 and 9-3 ).

FIGURE 9-2 Wavy coronal incision used in pediatric cranial vault surgery. A, Preoperative view of secondary surgery shows intermingling of the hair and hiding of the scar. B, The scalp is shaved, showing the width and pattern of the scar that is fairly well hidden despite being wider than desired.

FIGURE 9-3 A broken-line, irregular coronal incision makes the hair intermingle, producing improved camouflage of the scar. A, Preoperative incision marking for frontal access. B, Six-month postoperative view through short hair. - •

The incision is cut with a scalpel down to the galea below the hair follicles. A thermal cautery may be used thereafter without increasing postoperative alopecia around the scar. Injectable vasoconstriction, clamps, or running sutures are hemostatic measures that are preferable to electrocautery for the skin edges.

- •

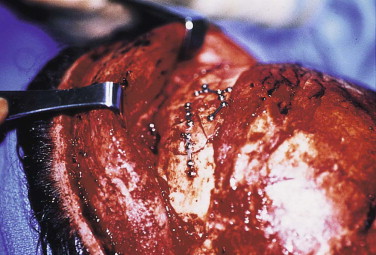

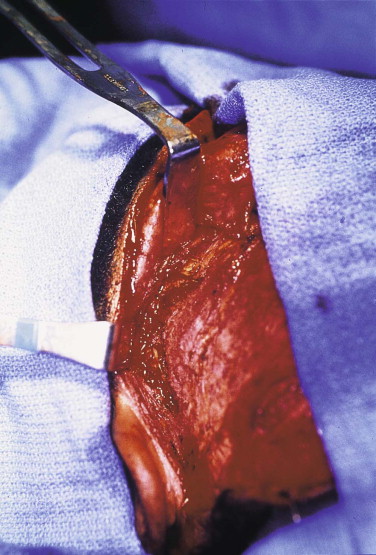

The scalp flap is raised forward in the subgaleal level. The periosteum is incised only directly above the bone area to be treated. This limits the amount of bleeding bone surface ( Fig. 9-4 ).

FIGURE 9-4 Frontal sinus fracture repair. The periosteum is incised and raised only directly above the operative site; this limits bone bleeding in the repair site. - •

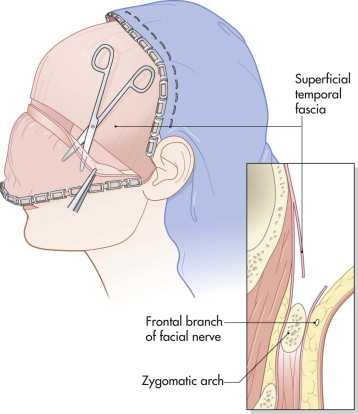

To avoid injury to the frontal branch of the facial nerve, the surgeon stays at the deep temporal fascial level. The nerve lies lateral to the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia ( Fig. 9-5 ). The periosteum is incised on the superior surface of the zygoma and zygomatic arch, which then reflects the superficial fascia outward, protecting the nerve ( Fig. 9-6 ; see Fig. 9-5 ).

FIGURE 9-5 Location of the frontal branch of the facial nerve in the temporal area. Incision of the deep temporal fascia 1 to 2 cm above the zygomatic arch with dissection directly onto the arch protects the nerve branch superiorly.

FIGURE 9-6 The scalp flap is raised down to the zygomatic arch. The frontal branch of the facial nerve is protected by incising the deep temporal fascia above the arch and then continuing toward the bone. - •

Across the supraorbital rim, the neurovascular bundle is dissected from the notch. When it is a foramen, an ostectomy is done to release the bundle. Dissection can be carried onto the nasal bones and medial orbits easily. The lacrimal sac and medial canthal tendons provide landmarks ( Fig. 9-7 ).

FIGURE 9-7 The scalp flap can be elevated easily and safely over the bony nose and medial orbits for access, as in this Le Fort III fracture repair. - •

Before closure, all soft tissues are resuspended if necessary, including the lateral canthal tendon and the temporalis muscle.

- •

The scalp skin closure should be done in two layers with nonstrangulating (noninterlocking) sutures or staples.

Endoscopic scalp access is of limited value in facial trauma and is used almost exclusively in endoscopic brow lifting, but this approach may achieve wider application in the future as endoscopic techniques and instrumentation improve. At least two incisions are required; the endoscope (nondominant hand) is placed through one and instruments (dominant hand) through the second incision. These incisions are small (1-2 cm long) and are placed immediately behind and perpendicular to the frontal or temporal hairline ( Fig. 9-8 ). Two or four incisions may be used, depending on the extent of dissection needed across the supraorbital and frontal areas.

Temporal Access

The smallest incision used for facial fracture repair is the transtemporal or classic Gilles approach. Its use is limited strictly to repair of zygomatic fractures, most commonly the zygomatic arch. Traditionally, its very small size was used for blind manual instrumentation of the arch or zygomatic body. With the advent of endoscopic techniques, it can also serve as a portal for instrument or endoscope insertion.

Technical Points

- •

The incision is placed several centimeters behind the frontotemporal hairline.

- •

Dissection proceeds directly down to and through the deep temporal fascia. This permits instruments to be directed along the temporal bone inferiorly ( Fig. 9-9 ). The superior branches of the facial nerve are vulnerable in this approach. The incision should be high and posterior to allow the nerves to be lifted out of the surgical field by remaining deep to the deep temporal fascia.

FIGURE 9-9 Small temporal incision for instrument manipulation of the zygomatic arch.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses