The maxillofacial region is in many ways anatomically unique. In the past, failure to appreciate its differences from the rest of the bony skeleton led to poor outcomes and unnecessary morbidity, particularly in the management of trauma. Although maxillofacial surgeons have used experience and research from general orthopedics to great effect, the mindless transfer of orthopedic techniques and principles is sometimes unhelpful. It must be recognized that surgeons are vulnerable to the market forces created by the manufacturers of fixation devices, although the same companies have, of course, introduced highly effective innovations. Proper evaluation of fixation techniques takes many years, so it is a long time before the shortcomings of some devices become apparent. Surgeons must not be seduced by the latest innovations but should always critically assess new devices and ideas and scrutinize relevant supporting publications. A thorough audit of outcomes by surgeons free from commercial pressures should allow well-informed decisions about new techniques.

Two innovations from general orthopedics—osteogenic distraction and bioresorbable fixation devices—have much to offer the maxillofacial traumatologist, and they are strongly promoted by the supply industry. They may not, however, be the ultimate answer to our surgical requirements in the way that the sales teams would have us believe. Although innovation is the precursor of progress, many new techniques, instruments, and materials do not stand the test of time.

The stigma of unreduced, unstable facial fractures can be severe. Minor cosmetic changes after facial injuries are common, and in modern societies, good results are often not enough: Perfection is demanded. For the surgeon, a less than perfect outcome is always unsatisfactory. Poor cosmetic and functional outcomes have several causes:

- •

Incorrect choice of surgical access. Because all skin incisions have the potential to form bad scars, hidden or mucosal incisions should be used wherever possible ( Figs. 7-1 through 7-4 ).

FIGURE 7-1 Use of an existing laceration is desirable, especially in this position which is difficult to access by other routes.

FIGURE 7-2 This laceration gave excellent access, and a good scar resulted from careful closure.(Copyright Media Studio, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.)

FIGURE 7-3 This intraoral incision provided excellent access to the extensive midfacial injuries, but further incisions were necessary to repair the periorbital fractures.

FIGURE 7-4 This retromandibular scar has healed well after open reduction and internal fixation of a condylar fracture. It demonstrates the appropriate use of a skin crease incision. - •

Inability to operate early. Normal skin draping is prevented if early healing has begun.

- •

Poor timing of surgery. For example, excessive swelling makes the precise placement of incisions difficult ( Fig. 7-5 ).

FIGURE 7-5 Excessive swelling will make it difficult to get a good result with any periorbital scar, and delay may be the best course. - •

Poor reduction of bone fractures. Closed reduction always has the risk of poor reduction.

- •

Poor understanding of the fracture sites. Lack of knowledge, usually because of inadequate clinical and radiological examinations, can lead to poor reduction and stabilization.

Posttraumatic functional problems may be more significant than any esthetic considerations, and these patients often feel markedly disabled. Typical functional problems include the following:

- •

Excessive scar tissue after poor primary care; inadequate wound cleaning and suturing

- •

Disabling visual problems, such as loss of vision or diplopia, with or without enophthalmos

- •

Loss of masticatory efficiency from iatrogenic malocclusion

- •

Impairment of speech and swallowing (rare)

- •

Persistent epiphora after ectropion

- •

Troublesome anosmia after midface fractures (rare)

- •

Motor or sensory neurological damage, which is common early after trauma and can persist, producing significant problems

Inadequate reduction and stabilization are the most common causes of esthetic and functional problems, even in less severe cases. These problems may also be associated with pain or chronic infection, although less often than in general orthopedic practice. Inadequate reduction and stabilization may not be as rare as we would like, but only careful follow-up and evaluation can establish the incidence.

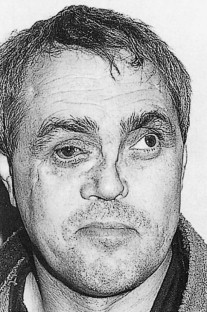

Poor outcomes may result from patients’ not seeking treatment ( Fig. 7-6 ). In less severe cases, it is sometimes difficult to determine what constitutes a perfect result. The aim of reduction and stabilization is to return the patient to the pre-injury status. The morbidity of the surgery must not exceed that of the traumatic injury itself (e.g., inappropriate and overzealous open reduction of an uncomplicated, minimally displaced orbital rim fracture). It is important to remember that bone is a living structure that will remodel, especially in young patients.

More difficult decisions have to be made in third world countries, where resources and manpower are limited. Is it reasonable to undertake a 1-hour open reduction of a fractured malar or to accept the less than perfect reduction achieved by a closed lift procedure? Similarly in the industrialized world, should surgeons spend a long time reducing a nasal fracture in a pugilist who will probably reappear with a fractured nose again in 3 months? The senior physician must make these decisions on an individual basis, with full consultation with the patient and or family. It is, however, important to have targets of excellence, which may be modified in light of an individual patient’s circumstances.

Suboptimal outcomes that are unrelated to socioeconomic factors (e.g., failing to present for care after a fracture) are not uncommon, but only by careful follow-up and evaluation can the outcome be fully established. Poor outcomes may occur for a variety of other reasons, which may be beyond the control of the maxillofacial surgeon:

- •

Coexisting medical problems, particularly head injuries ( Fig. 7-7 ), may delay definitive surgery, making it difficult to achieve good reduction. Secondary correction of initial problems is rarely as good as primary surgery.

FIGURE 7-7 In addition to his facial injuries, this patient suffered intracranial trauma, which necessarily delayed treatment. In the end, his injuries were managed nonoperatively.(Copyright Media Studio, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.) - •

Inadequate preoperative investigations, particularly if there is lack of appropriate imaging, may fail to reveal the true extent of the bony injuries. It is acceptable to delay surgery until adequate plain radiographs and scans are available ( Figs 7-8 and 7-9 ).

FIGURE 7-8 A useless radiograph resulted from an uncooperative patient who moved during imaging.

FIGURE 7-9 A three-dimensional computed tomogram provides good information about the number and pattern of facial fractures, but it must be interpreted in light of the clinical findings, and its shortfalls must be appreciated. In this case, the artifact caused by amalgam dental restorations obscure the mandibular ramus.(Copyright Media Studio, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.) - •

Inadequate surgical planning, notably failing to plan the surgical access or the need for bone for grafting, affects results. Adequate patient consent requires that these important eventualities be considered and discussed before any procedure is initiated.

- •

Very severe fractures, particularly grossly comminuted fractures, can be extremely difficult to reduce and stabilize. These technical difficulties can be overcome only by experienced surgeons with a special interest in facial trauma.

- •

Some surgeons (often from anatomically related specialties) with limited experience in facial trauma may not fully appreciate the structure and function of the oral and maxillofacial region and may therefore attain less than ideal results.

- •

Patients who are from poor socioeconomic backgrounds or who abuse alcohol or drugs may refuse or fail to present for treatment. These patients then may require secondary procedures.

We believe that if there is a logical approach to reduction and fixation many of these poor outcomes can be minimized.

Principles of Reduction

Open or Closed?

Terminology in this field can be confusing. The terms closed and open treatment are preferred to conservative and operative . Open refers to deliberate surgical intervention to open and directly explore the fracture site, normally by means of a surgical incision or a laceration. Fractures involving the teeth-bearing areas are biologically open, although this does not normally afford surgical access. Some surgeons refer to intermaxillary wiring as conservative treatment, but others refer to a soft diet alone as conservative management. The use of intermaxillary fixation (IMF) (also called mandibular maxillary fixation [MMF]) has well-documented morbidity and mortality rates that do not fit with the concept of conservative management.

The term open refers to exposure, reduction, and fixation of the fracture under direct vision. Closed refers to no direct visualization of the fracture site; that is, blind fixation, which usually is achieved indirectly or by relying on nonsurgical stabilization, like IMF (MMF).

The vague term conservative may mean no treatment of any kind, no surgical treatment, or, for some surgeons, the use of IMF. It is better to use more specific terms such as wait and watch , nonsurgical , or, preferably, closed treatment.

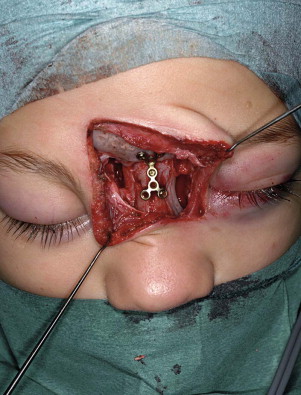

Not all displaced fractures need reduction. However, only severe medical problems obviating general anesthesia should prevent open reduction if it is otherwise indicated. Many fractures can be treated by open reduction with the use of sedation and local anesthesia. Open reduction involves exposure of the fracture through the skin or mucosa (surgical exposure is discussed later). Once opened, the fracture can be reduced and directly fixed through the incision ( Fig. 7-10 ). Closed reduction is blind reduction and relies on the fragments’ locking together. This is more likely to be successful if the periosteum is largely intact. Examples of closed reduction include fixation of the teeth in occlusion (i.e., IMF), elevation of a fractured zygoma, and use of an arch bar to stabilize dentoalveolar fractures. In these circumstances, reduction usually occurs without direct visualization of the fragments in their final position.

In maxillofacial surgery, the most common method of closed treatment is IMF, which relies on the correct positioning of the teeth to control the reduction. For mandibular fractures, open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) has traditionally been performed with the use of temporary intraoperative IMF to secure the occlusion before plate placement. Although the IMF is released at the end of the operation, it may be reapplied if necessary. This belt-and-braces approach may be questioned for several reasons. First, operating time is reduced if IMF is not used. Second, although this is a more certain reduction for the surgeon, is it more comfortable for the patient? Moreover, there is ample evidence of short- and long-term risk to the patient when IMF is used. Evidence indicates it may damage the periodontium and reduce airflow, and weight loss and long-term temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function may be adversely affected.

Fifty years ago, facial fractures were typically managed by closed methods. Open reduction was reserved for cutaneous compound fractures or certain unstable mandibular fractures. This evolution toward open reduction has improved the precision of the reduction, because the fragments can be carefully examined and manipulated. What led to this change in philosophy?

In the pre-antibiotic era and before modern aseptic techniques, surgeons were extremely cautious about open reduction. Experience, particularly from general orthopedic practice, suggested that open reduction almost invariably led to local infection, severe osteomyelitis, and even death of the patient. Caution about open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) was fueled by the lack of suitable implant material with which to stabilize the fracture. This problem continued beyond the introduction of modern sterile techniques and antibiotics. Although more suitable implants became available, the biomechanics of the systems often lacked a scientific basis. Bad experiences created a climate of antipathy toward routine open reduction.

Historically, the avoidance of ORIF was based on sound surgical principles that were difficult to achieve for a variety of reasons. In modern surgery, with excellent plating and fixation systems and with safe, largely infection-free surgical procedures, these principles are relatively easy to achieve:

- •

Open reduction should be used only if the procedure itself does not have a significant or unacceptable morbidity.

- •

Open reduction should be followed by direct fixation of the fracture to ensure that the full benefits of the procedure are gained.

Closed Reduction

Disadvantages of Closed Reduction

Closed reduction can be problematic. With this method, the position of the teeth, palpation, and postoperative radiographs are used as guides to the accuracy of reduction. The most common problem with closed reduction is poor fracture alignment. In many cases, closed reduction relies on correct positioning of the teeth, on the assumption that this produces correct orientation of the bony fragments. Although the occlusion must be correctly restored, the teeth have only a limited effect on the final position of the bones. This influence significantly diminishes as fractures extend away from the dental arches, such as in the zygomatic complex, which is not related to the teeth. Even in mandibular fractures, muscle tone and activity may displace bone fragments despite firm location of the teeth.

This problem becomes compounded in cases of preexisting malocclusion, which is a common predisposition to mandibular fractures. In cases of a depleted dentition or injury to the teeth themselves, reduction of the occlusion becomes a less reliable method of reducing the bony fractures. Errors of reduction are tolerated much less in facial fractures than in other orthopedic procedures. Inadequate reduction, even in the presence of a normal occlusion, may be associated with poor esthetics and functional problems. Facial fractures are most common in the young, and it is unacceptable to leave these patients with long-standing facial deformity or dysfunction.

Closed reduction for maxillary and mandibular fractures demands IMF. This is a technically simple procedure that may not require general anesthesia, although it has several disadvantages Patients dislike IMF, and it can be dangerous by obstructing the airway.

Closed reduction relying on the dentition has little value in the treatment of upper facial injuries and none in isolated zygoma, orbital, or nasal fractures. Closed reduction of upper facial fractures relies on palpation to ensure reduction and on periosteal attachment to provide stability, neither of which can be guaranteed preoperatively or intraoperatively. In the past, external fixation, typically pin fixation, was performed, with antral or nasal packs used in an attempt to provide stability. However, the nature of these gauze packs ensured only limited stability, and even if the surgeon was optimistic, the experience of having these packs removed usually failed to persuade the patient of their value.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses