Injuries to the face commonly result in a significant psychological response that is unparalleled by the response to injury elsewhere on the body, especially if it is the result of interpersonal violence. The importance of facial appearance in modern society and its implication in vocational and social status makes changes to facial features, particularly by injury, an emotionally charged occurrence. Patients fear facial disfigurement and scars and risk loss of their self-esteem. Surgical repair of facial injuries is understandably associated with high expectations of a complete return to a normal facial appearance. Often the final result, fairly or unfairly, is judged to be a reflection of the surgeon’s skill and ability.

In addition to the obvious skin and mucosal involvement, facial trauma frequently includes injury to the deeper hard and soft tissue structures. Understanding the mechanism of injury and the anatomy of the region is essential for satisfactory management.

Wound Assessment

History and Examination

Apart from general aspects of the history that are common to all patient contacts, a complete history of the incident leading to the injury should be taken, and if not available from the patient, the details should be obtained from anyone present at the time of the incident or those in immediate attendance after. Understanding the mechanism of injury will alert the surgeon to the possibility of associated injury or contamination (e.g., bacteria, viruses, foreign bodies) and sequelae that may not otherwise be apparent. For example, when dealing with a penetrating knife wound, it is necessary to know the type of weapon, the degree of force used, and the postures of the patient and the assailant when the injury was caused to assess the degree of tissue damage and possible contamination, the depth and direction of penetration, and the possibility of involvement of deeper structures. Similarly, when the injury results from a road traffic accident, the type of accident (e.g., motorcycle, car), the position of the patient in the accident (e.g., pedestrian, driver, passenger), and the circumstances and relative speeds of the vehicles involved alert the surgeon to the possibility of associated injury underlying the presenting facial trauma or involving other systems.

The specialized nature of facial structures demand that particular attention be paid to injuries of different facial regions. Lacerations to the brow, eyelid, nose, lip, and ear require careful assessment and treatment to avoid deformity and potential interference with function. Lacerations to the lateral face, temple, and naso-orbital regions risk injury to branches of the facial nerve and to the parotid and lacrimal ducts. Injuries to the eyelid and orbit typically require ophthalmological evaluation to establish visual status and the presence or absence of corneal damage.

The tetanus immunization status of the patient is an essential part of the general medical history. Although facial wounds often appear to be clean, the patient is still at risk and requires tetanus prophylaxis. For clean minor wounds, no treatment is necessary if the immunization status is current. If more than 10 years has elapsed since the last booster injection, tetanus toxoid should be given. All patients with contaminated wounds should receive tetanus toxoid unless they have been immunized within the past 5 years.

Biomechanics

An appreciation of the concept of relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) of the face is relevant to treatment and outcome. In a cadaver model exposed to blunt facial trauma, the induced soft tissue lacerations parallel the cleavage lines of the face (i.e., RSTLs) and were more severe on the forehead than on the zygoma or maxilla. These injuries were inherent in the biomechanical and structural property of the dermis of the skin and independent of muscle or bony attachments. It has been postulated that the direction of skin lacerations in blunt trauma occurs as a protective mechanism to minimize injury to the underlying blood supply because the vessels and collagen bundles parallel the RSTLs ( Fig. 6-1 ). The esthetic outcome of skin injuries is partially related to their relation to the RSTLs; scars have a better prognosis if they parallel the RSTLs or are in natural skin creases. With immediate repair and if the laceration is irregular but parallels the RSTLs, it can be excised and closed as a straight line. If it runs perpendicular or oblique to the RSTL, it should be closed as it manifests because the irregularities may offer better camouflage of the resultant scar.

Excluding Fractures During Assessment

Evaluation must exclude bone injuries. This failure can occur in busy trauma units when several specialists are involved in the patient’s care and there is a desire to quickly treat the soft tissue injuries by a surgeon less familiar with hard tissue trauma.

Classification of Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue trauma of the face may be classified according to the tissue insult (i.e., contusions, abrasions, lacerations, avulsions, and chemical or thermal burns) or the mechanism of injury (e.g., dog bite), which often involves a combination of the former elements.

Contusion

Blunt trauma to the face always results in some degree of swelling and bruising, depending on the area involved. Eyelids or lips, for example, develop a greater amount of swelling than forehead or cheek tissues. If subcutaneous vessels are ruptured, a hematoma may occur, which may or may not require primary or secondary management. Most facial contusions have no specific treatment, with the exception of ear or septal hematomas, which require immediate evacuation.

Many facial lacerations have contusions at their skin edges that require sharp débridement to minimize the long-term risks of adverse scarring, pigmented changes, and underlying soft tissue atrophy. Red dermal bleeding is the hallmark of viable skin, and these tissues usually should not be débrided.

Abrasion

Most abrasions that occur on the face are superficial and involve loss of the epithelium and exposed papillary dermis. These injuries will heal quite rapidly with topical agents ( Fig. 6-2 ). Impact of the face against particulate surfaces (e.g., asphalt, gravel) or exposure to explosive charges (e.g., powder burns from gunshots) usually results in the implantation of foreign material. Frictional contact with otherwise benign particulate matter results in dermal exposure and injury that may mimic a second- or third-degree burn, depending on the depth. If allowed to heal, the growth of new epithelium over the contamination results in the phenomenon known as traumatic tattooing , which leads to permanent discoloration ( Fig. 6-3 ). Prevention requires meticulous débridement and occasionally may necessitate the use of a dermabrader. Petroleum-based liquids, such as grease and oil, can be removed with organic solvents such as acetone or ether. After adequate cleansing, the partially denuded dermis may be covered with antibiotic ointment alone or medicated nonadherent gauze dressing (e.g., Xeroform). Complete healing by re-epitheliazation occurs within 7 to 10 days, and erythema resolves within several months thereafter.

Lacerations

Facial lacerations occur as a variety of specific types, which affect the risks of scarring and eventual need for scar revision. Recognition of these forms permits modifications in the surgical repair techniques.

Sharp objects usually create wounds with clean, straight edges that are easy to repair and produce fine scars. Minimal or no débridement is necessary, and the apposition of tissues is done with a layered closure. Because sharp objects often penetrate deeper than initially perceived, careful exploration of the wound should be carried out in areas where vital structures lie underneath. Revision of linear scars often is not needed ( Fig. 6-4 ) unless they violate the RSTL, in which case they may be improved by geometric rearrangement.

Stellate lacerations usually result from blunt injury, explosions, or crushing forces, which strike with enough force in a single area to “fracture” the surrounding tissue in noncleavage planes. Multiple flaps of skin are created, often with contused edges, around a more central area of tissue damage or loss ( Fig. 6-5 ). The elastic recoil of the skin often gives the false perception of significant tissue loss. This type of laceration should be repaired as it is positioned, and only grossly nonviable tissue should be débrided. Despite the best initial repair, these lacerations often heal poorly, and many require secondary revision.

Tangential lacerations that undermine and lift up skin edges or lacerations that have a curvilinear or semicircular shape result in a trapdoor deformity. The laceration heals with a mound of tissue on its concave side due to contracture from unopposed fibrosis and from lymphatic and venous obstruction ( Fig. 6-6 ). By creating a sharp, vertical edge on the flap side, undermining the undersurface of the side opposite to the flap, advancing it at the same level, and placing the initial suture support deep to the dermis between the flap and the surrounding tissue (see Fig. 6-6 ), the deformity may be averted or at least reduced.

Avulsions

Facial defects due to traumatic avulsion are relatively uncommon, occurring almost exclusively from gunshot or large, sharp-edged weapon injuries. For small defects, the surrounding tissue can be mobilized and the defect closed. The use of local random flaps or pedicle flaps should be discouraged during the initial repair, because the viability of surrounding tissues can be difficult to evaluate in the primary setting. For larger defects that are not amenable to primary closure, wet-to-dry dressings can be placed until the appropriate time for reconstruction. These dressings can be used for long periods as the zone of viability demarcates and granulation tissue develops. In more uncommon circumstances, the avulsion defect can initially be covered with a split-thickness skin graft. This allows the facial wound to heal before more complex methods of facial reconstruction with better esthetic outcome are carried out at a later time (e.g., tissue expansion, serial graft excision, local flaps) ( Fig. 6-7 ).

Bites

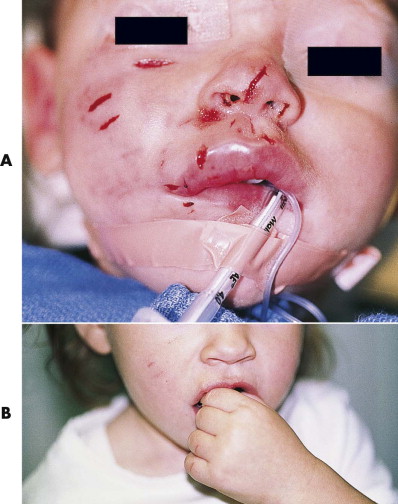

Bite wounds, even on the well-vascularized face, have a significant risk of infection because of their high rate of contamination. They introduce highly infective bacterial flora, and the bite wound is often a combination of multiple types of damage, including penetrating, contusing, and avulsing injuries. Bites come from animals or humans, and each has its own distinctive bacterial content. Animal bites, particularly from dogs, are polymicrobial and include Staphylococcus aureus , β-hemolytic streptococci, and the anaerobes Bacteroides and Fusobacterium . Pasteurella multocida also may be found, especially in cat bites. Human flora usually has a higher concentration of anaerobes such as Bacteroides and commonly contains Staphylococcus and α-hemolytic streptococci. Differences also exist in bite wound locations; human bites are far more prevalent on the lips, nose, and ear, whereas most animal bites are more random, involve more surface area, and are more avulsive due to the innate pull-back response of the victim.

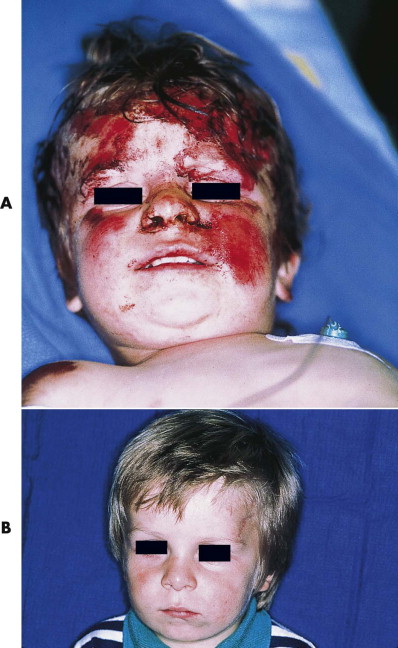

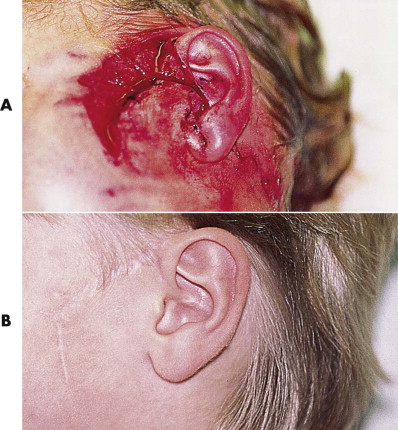

For most wounds that are seen within 24 hours, primary treatment includes operative irrigation, limited débridement, and primary closure. With this approach, the infection risk is low, and the resultant scars are better ( Fig. 6-8 ). Only small puncture wounds are left to heal secondarily. For wounds that occurred more than 24 hours earlier or large avulsion injuries, closure is controversial. We prefer primary closure because the infection risk is higher and thereby hope to obtain more expeditious treatment and a better scar. Some surgeons prefer delaying closure of these wounds for up to 1 week, although whether this decreases the risk of infection is not clear. Adjunctive pharmacological treatment is essential, usually consisting of broad-spectrum (i.e., combined aerobe-anaerobic coverage) antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin with clavulanic acid), tetanus immunization, and rabies prophylaxis as necessary.

Documentation

Facial injuries should be documented because patients may benefit and cope better with the outcome if they are able to compare the outcome with the original injury and because the injury may at some point be the subject of a medicolegal action, and accurate recording, preferably with photographs, can facilitate the process.

Recording injuries on a handwritten facial cartoon is the most primitive method. One method of documenting facial information is the MCFONTZL classification system, which represents a simplified method of recording blunt facial soft tissue injuries. The system divides the face into 12 esthetic units (right and left in some cases) using the mnemonic MCFONTZL: maxilla, chin, forehead, orbit, nose, temple, zygoma, lips. The soft tissue laceration is recorded using an ASTERISK notation scheme: area (MCFONTZL esthetic unit designation), side, thickness (depth of penetration), extension (branching), relaxed skin tension conformation (directionality), index laceration (laceration with the maximal continuous skin interruption), soft tissue defect (presence or absence), and coding (current procedural terminology). The information is recorded along the rays of the asterisk symbol in a clockwise direction. However, conventional color slides or prints document the injuries in such a graphic and detailed manner that they should be the method of choice when possible. Digital photography may gradually replace conventional light photography, although it may be more prone to exploitation.

Excluding Fractures During Assessment

Evaluation must exclude bone injuries. This failure can occur in busy trauma units when several specialists are involved in the patient’s care and there is a desire to quickly treat the soft tissue injuries by a surgeon less familiar with hard tissue trauma.

Classification of Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue trauma of the face may be classified according to the tissue insult (i.e., contusions, abrasions, lacerations, avulsions, and chemical or thermal burns) or the mechanism of injury (e.g., dog bite), which often involves a combination of the former elements.

Contusion

Blunt trauma to the face always results in some degree of swelling and bruising, depending on the area involved. Eyelids or lips, for example, develop a greater amount of swelling than forehead or cheek tissues. If subcutaneous vessels are ruptured, a hematoma may occur, which may or may not require primary or secondary management. Most facial contusions have no specific treatment, with the exception of ear or septal hematomas, which require immediate evacuation.

Many facial lacerations have contusions at their skin edges that require sharp débridement to minimize the long-term risks of adverse scarring, pigmented changes, and underlying soft tissue atrophy. Red dermal bleeding is the hallmark of viable skin, and these tissues usually should not be débrided.

Abrasion

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses