Chapter 4

Primary molar adhesive tooth restoration

Constance M. Killian and Theodore Croll

Introduction

Sixty years ago, when Hogeboom (1953) offered the Sixth edition of his classic pediatric dentistry textbook, Practical Pedodontia or Juvenile Operative Dentistry and Public Health Dentistry, the materials used to repair primary teeth were as follows: “gutta-percha,” black copper cement, Fleck’s Red Copper Cement, silver amalgam, copper amalgam, Kryptex (“a good silicate”), silver nitrate, ammoniated silver nitrate, chromium alloy deciduous crowns, and rapid setting plastic filling materials (requiring “ample pulp protection”). Stainless steel crowns are still very useful and are known for their durability and reliability. “Plastic” filling materials have made their way to the forefront of direct application restorative dentistry, but today’s materials have little resemblance to the original resin products. Silver amalgams are still used by some dentists for repair of primary teeth, but because they do not bond to tooth structure, have a dark color, and suffer from the continuing false controversy over their safety, they are being offered to parents less and less.

An ideal direct application dental restorative material for primary molars would be biocompatible and tooth colored, adhere to tooth structure with no subsequent marginal leakage, have sufficient physical properties so as not degrade in the mouth, have “on-command” hardening after applied to tooth structure, and handle easily for the practitioner.

Decades of progress have brought us advanced direct placement restoratives that come close to meeting all the above-mentioned requirements to be considered ideal. Resin-based composites (RBCs) and the glass polyalkenoate (glass ionomer) systems have been at the forefront of the “adhesive dentistry” revolution that has immeasurably progressed restorative dentistry for children. Berg (1998) succinctly reviewed modern adhesive restorative materials that are useful in clinical pediatric dentistry.

The ideal operative field: rubber dam isolation

The use of adhesive materials for restoring carious, malformed, or fractured primary molars demands careful attention for moisture control. Many adhesive materials, particularly RBCs, are sensitive to moisture and require isolation of teeth to be treated. There is no better way to achieve such isolation and create an ideal operative field than the rubber dam.

Dr. Sanford Barnum first used a “rubber cloth” to isolate a mandibular molar of R.C. Benedict on March 15, 1864 (Christen, 1977). From that time on, that manner of isolating teeth became the standard protocol in the profession for restorative dentistry (Francis, 1865; Barbakow, 1964). Croll (1985) listed the following benefits of rubber dam use.

- Operating time is reduced.

- Visibility for the dentist is improved.

- Tongue and cheek are protected and out of the way.

- The mouth stays moist and more comfortable for the patient.

- The patient is protected from aspirating or swallowing excess material, water spray, infected tooth substance, or broken instrument fragments.

- Soft tissues in region of operation are better protected from accidental engagement.

- Risk of pulpal contamination is decreased once pulp space is exposed.

- Superfluous patient conversation is decreased.

- Patients become more relaxed and feel safer.

- A dry operating field is much easier to establish and maintain.

Because of the anatomical form of primary molars, stringent tooth-by-tooth application of a rubber dam, as taught in dental schools, can be quite difficult, frustrating, and time-consuming in restorative dentistry for young patients. The rubber dam procedure does not need to be abandoned, however. The “slit dam” technique is an easier but very effective way to apply rubber dam for the restoration of primary molars (Croll, 1985). The steps for isolation using the slit dam technique are as follows.

- Select an appropriate rubber dam clamp and secure an 18-in. piece of dental floss to the loop of the clamp.

- Place the rubber dam on the frame. For pediatric patients, a 5-in. frame is typically sufficient (“nonlatex” dam should be used for patients with sensitivity or allergy to latex).

- Punch two holes in the dam, one for the most posterior tooth to be isolated and the other for the most anterior tooth to be isolated.

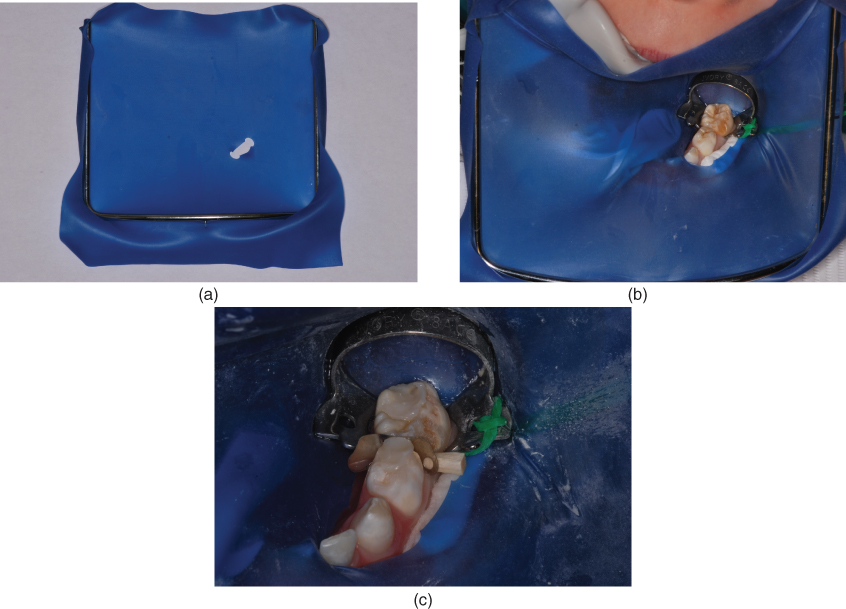

- Using scissors cut a slit to connect the two holes in the dam (Figure 4.1).

- Use rubber dam forceps to seat the selected clamp onto the most posterior tooth being isolated.

- Carefully stretch the rubber dam over the clamp, extending it to reveal the quadrant being treated. If necessary, a piece of dental floss or a wooden wedge may be used to secure the dam to the mesial aspect of the most anterior tooth.

Figure 4.1 (a) Typical placement of holes and slit in rubber dam for mandibular teeth. (b) Rubber dam in place, demonstrating “slit dam” technique. Note placement of Molt mouthprop for patient comfort and bite stability. In addition, a cotton roll has been placed in the buccal vestibule for dry isolation. (c) Close-up view of “slit dam” in place creating an ideal operative field.

Figure 4.1a–4.1c shows the slit dam being used to isolate the teeth to be restored.

Adhesive primary molar tooth restoration

Because of the availability of preventive and restorative dental materials that can micromechanically or chemically bond to tooth structure, much has changed over the last three decades. The term “adhesive dentistry” applies to certain categories of dental materials, including pit and fissure sealants, resin-based composites (RBCs), compomers (COs), and glass ionomer (GI) systems including resin-modified glass ionomers (RMGIs). Practitioners should be familiar with the indications for the various materials and fully understand the advantages and disadvantages of each. Awareness of limitations of each class of material and those of specific brands is essential to success with their use. Knowledge of the handling characteristics of each material is also critical to assure that all the advantages of their use will be optimized.

Pit and fissure sealants

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses