The nasoethmoid region is an important area of the face for cosmesis and determining facial projection and width. The region relies for form and strength on a complex interrelationship between uniquely specialized soft tissues and bones formed into buttresses and thin plates.

Nasoethmoid fractures represent a spectrum of injury from simple nasal fractures with minimal ethmoidal involvement to grossly comminuted fractures with displacement. The complex anatomy and direction of the force, together with the degree of development of the paranasal sinuses and related structures, often mean that the fracture patterns extend posteriorly into the orbit, the skull base, and the frontal sinus. Fractures of the frontonasal duct as it traverses the anterior part of the labyrinth of the ethmoid should be considered in all nasoethmoid fractures. In more than 50% of individuals, the frontonasal duct is continuous with the anterior ethmoidal sinus through the infundibulum, which means that all nasoethmoid fractures should be considered to be compound fractures. Nasoethmoid injuries should also be considered as fractures of the orbit, with all their associated problems.

State of the Art

Management of these injuries requires a thorough understanding of the anatomy. Because standard textbooks do not emphasize certain important aspects of surgical anatomy, it is a controversial area. The surgical anatomy is extensively reviewed later in this chapter (see “ Controversies ”).

The gold standard of care of patients with nasoethmoid injuries begins with a careful clinical evaluation, which includes a detailed radiologic examination and careful ophthalmic examination. Rarely, secondary examinations are done, particularly to verify the function of the lacrimal apparatus. This protocol should establish a precise diagnosis. With this information, typically using an open approach, precise reduction and stabilization should be possible, leading to a good outcome.

Clinical Examination

The clinical findings are related to the time of examination of the patient after injury. Soft tissue injuries usually can be readily evaluated by clinical examination, but gross edema or emphysema initially may mask the full extent of the injuries. If the patient is examined soon after the injury, gross swelling may mask canthal detachment ( Fig. 12-1 ).

Nasoethmoid fractures may manifest with traumatic telecanthus and impaction of the bridge of the nose, producing the characteristic appearance ( Fig. 12-2 ). Telescoping of the nasal dorsum into the ethmoidal region ( Fig. 12-3 ) and the lack of distal support lead to nasal tip elevation. Depression of the nasal bridge with lack of normal form in the frontonasal angle projects the nostrils almost horizontally, producing a pig snout appearance when the swelling has subsided ( Fig. 12-4 ).

Some workers have attempted to classify these bony fractures. The classifications are infrequently used because they have not proved useful in clinical practice and do not correlate well with outcome. It is, however, important to determine the severity of the fracture. Greater problems occur with compound, comminuted fractures with gross displacement than with simple fractures. In nasoethmoid trauma, comminution and detachment from bone of the canthus represent important, poor prognostic criteria for a satisfactory outcome. Even later classifications do not consider damage to the lacrimal apparatus.

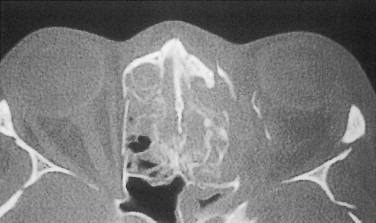

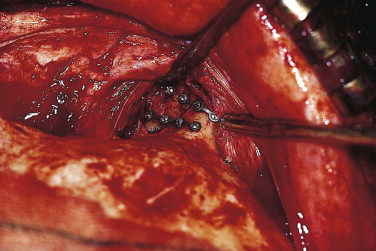

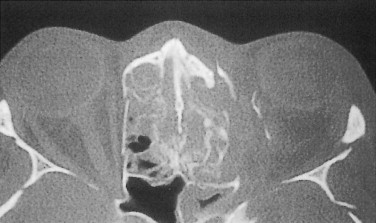

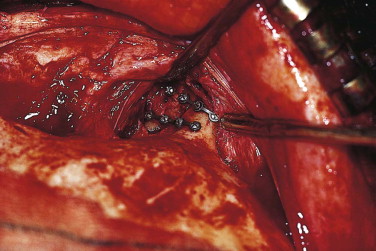

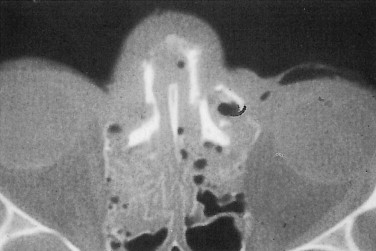

In trauma to this region, the bones most commonly fracture in such a way as to leave a fragment with the medial canthal ligament attached. However, the oblique slope of the nasal bones and their concavoconvexity from above down and their concavity anteroposteriorly mean that anterior forces can cause overriding of bony fragments. The fragments can be pushed posteriorly and disrupt the lacrimal sac ( Fig. 12-5 ) or guillotine the canthal ligament. This can be seen on computed tomography (CT) ( Fig. 12-6 ) and clinically, and careful exploration of lacerations in this area can reveal the extent of the damage to the canthal attachment ( Fig. 12-7 ) or lacrimal system, or both.

The eyelids should be held and distracted laterally. This maneuver is particularly directed at pulling the canthus to ensure it is still attached to stable bone. If the canthus is detached or the canthal-bearing bone fragment is small, the canthal apex will move laterally, and the canthal angle will be blunted ( Fig. 12-8 ). When the nasoethmoid fragments are severely impacted, the canthal-bearing fragment can become wedged in an incorrect position, and the distraction test result will be falsely negative.

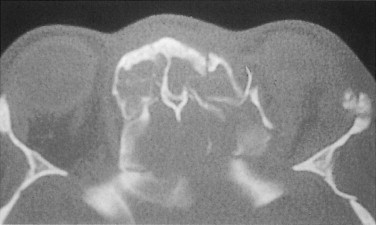

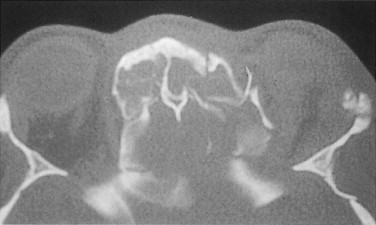

More severe forces may extend the fractures into the base of skull ( Fig. 12-9 ) through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid; this frequently is associated with a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Tears in the dura may occur if a fragment of misplaced bone punctures the membrane. Shearing forces may tear the dura, particularly if the crista galli is fractured, as often occurs with severely displaced nasoethmoid fractures. The energy of impact may also be dissipated through the frontal sinus, and fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus are commonly associated with high-energy trauma, causing severely displaced nasoethmoid fractures that extend into the skull base and anterior cranial fossa.

The midline of the patient’s face and asymmetry of the canthi are important indicators. The intercanthal and interpupillary distances should be measured. Although a gross increase in the intercanthal distance (range in whites, 24-39 mm) is diagnostic, borderline cases can be difficult. A better guide in clinical practice is to relate the intercanthal distance to the interpupillary distance, provided there is no globe displacement due to gross orbital disruption. The intercanthal distance typically is twice the interpupillary distance. If the bone attachment has been fractured and displaced laterally with the canthus, the situation needs to be explored more formally at the time of surgery in order to fix the medial canthus and prevent late complications of canthal drift.

A full ophthalmic examination is essential, but it may be compromised by the neurological status of the patient. The function of the optic nerve and the ocular reflexes must be examined. In a posteriorly impacted nasoethmoid fracture, the optic nerve can be compressed by collapse of the bony complex into the sphenoid sinus and direct compression of the nerve in the canal. In the unconscious patient, the swinging flashlight test is particularly important, and the fundus should be examined thoroughly for signs of optic nerve compression. Among patients who have sustained sufficient trauma to cause compression of the optic nerve, there is a high incidence of globe injuries.

The lacrimal apparatus is damaged infrequently, usually as a result of direct penetrating trauma or overriding fragments of sharp bone. Lacerations in this area must be carefully explored. Dye can be introduced into either of the lacrimal puncta, and backflow usually demonstrates the leak. If doubt remains, radiological confirmation may be needed.

Bony injuries are frequently difficult to examine well enough to give a precise diagnosis. Even in the most swollen patients, however, it is usually possible to gauge the extent of the fractures by careful clinical examination. This information is important for obtaining well-targeted radiographic examinations.

Clinical Examination

The clinical findings are related to the time of examination of the patient after injury. Soft tissue injuries usually can be readily evaluated by clinical examination, but gross edema or emphysema initially may mask the full extent of the injuries. If the patient is examined soon after the injury, gross swelling may mask canthal detachment ( Fig. 12-1 ).

Nasoethmoid fractures may manifest with traumatic telecanthus and impaction of the bridge of the nose, producing the characteristic appearance ( Fig. 12-2 ). Telescoping of the nasal dorsum into the ethmoidal region ( Fig. 12-3 ) and the lack of distal support lead to nasal tip elevation. Depression of the nasal bridge with lack of normal form in the frontonasal angle projects the nostrils almost horizontally, producing a pig snout appearance when the swelling has subsided ( Fig. 12-4 ).

Some workers have attempted to classify these bony fractures. The classifications are infrequently used because they have not proved useful in clinical practice and do not correlate well with outcome. It is, however, important to determine the severity of the fracture. Greater problems occur with compound, comminuted fractures with gross displacement than with simple fractures. In nasoethmoid trauma, comminution and detachment from bone of the canthus represent important, poor prognostic criteria for a satisfactory outcome. Even later classifications do not consider damage to the lacrimal apparatus.

In trauma to this region, the bones most commonly fracture in such a way as to leave a fragment with the medial canthal ligament attached. However, the oblique slope of the nasal bones and their concavoconvexity from above down and their concavity anteroposteriorly mean that anterior forces can cause overriding of bony fragments. The fragments can be pushed posteriorly and disrupt the lacrimal sac ( Fig. 12-5 ) or guillotine the canthal ligament. This can be seen on computed tomography (CT) ( Fig. 12-6 ) and clinically, and careful exploration of lacerations in this area can reveal the extent of the damage to the canthal attachment ( Fig. 12-7 ) or lacrimal system, or both.

The eyelids should be held and distracted laterally. This maneuver is particularly directed at pulling the canthus to ensure it is still attached to stable bone. If the canthus is detached or the canthal-bearing bone fragment is small, the canthal apex will move laterally, and the canthal angle will be blunted ( Fig. 12-8 ). When the nasoethmoid fragments are severely impacted, the canthal-bearing fragment can become wedged in an incorrect position, and the distraction test result will be falsely negative.

More severe forces may extend the fractures into the base of skull ( Fig. 12-9 ) through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid; this frequently is associated with a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Tears in the dura may occur if a fragment of misplaced bone punctures the membrane. Shearing forces may tear the dura, particularly if the crista galli is fractured, as often occurs with severely displaced nasoethmoid fractures. The energy of impact may also be dissipated through the frontal sinus, and fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus are commonly associated with high-energy trauma, causing severely displaced nasoethmoid fractures that extend into the skull base and anterior cranial fossa.

The midline of the patient’s face and asymmetry of the canthi are important indicators. The intercanthal and interpupillary distances should be measured. Although a gross increase in the intercanthal distance (range in whites, 24-39 mm) is diagnostic, borderline cases can be difficult. A better guide in clinical practice is to relate the intercanthal distance to the interpupillary distance, provided there is no globe displacement due to gross orbital disruption. The intercanthal distance typically is twice the interpupillary distance. If the bone attachment has been fractured and displaced laterally with the canthus, the situation needs to be explored more formally at the time of surgery in order to fix the medial canthus and prevent late complications of canthal drift.

A full ophthalmic examination is essential, but it may be compromised by the neurological status of the patient. The function of the optic nerve and the ocular reflexes must be examined. In a posteriorly impacted nasoethmoid fracture, the optic nerve can be compressed by collapse of the bony complex into the sphenoid sinus and direct compression of the nerve in the canal. In the unconscious patient, the swinging flashlight test is particularly important, and the fundus should be examined thoroughly for signs of optic nerve compression. Among patients who have sustained sufficient trauma to cause compression of the optic nerve, there is a high incidence of globe injuries.

The lacrimal apparatus is damaged infrequently, usually as a result of direct penetrating trauma or overriding fragments of sharp bone. Lacerations in this area must be carefully explored. Dye can be introduced into either of the lacrimal puncta, and backflow usually demonstrates the leak. If doubt remains, radiological confirmation may be needed.

Bony injuries are frequently difficult to examine well enough to give a precise diagnosis. Even in the most swollen patients, however, it is usually possible to gauge the extent of the fractures by careful clinical examination. This information is important for obtaining well-targeted radiographic examinations.

Radiological Examination

Good-quality radiographs are normally required, but in patients with marked swelling, the fine bones of the nasoethmoid region may be effaced by soft tissue shadows. Careful examination of the orbital and other facial bones is required. Occipitomental views (10- and 45-degree projections) are most helpful as an initial screening examination. Lateral face or skull radiographs are usually disappointing for evaluation of nasoethmoid trauma; occasionally, an occlusal film shows disruption of the ethmoid.

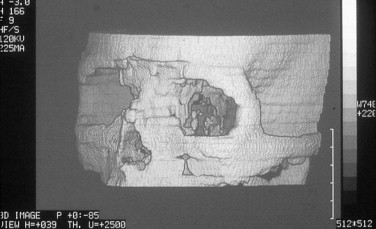

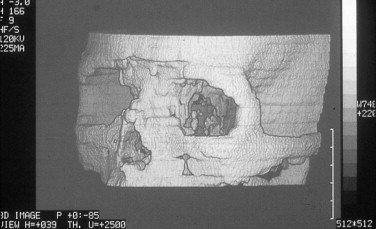

Good-quality CT scans are extremely valuable and can be essential, particularly for assessing high-energy trauma cases in which the frontal sinus and base of skull may be disrupted ( Fig. 12-10 ). Because reconstructed and three-dimensional images contain artifacts, it is helpful if the patient is fit enough to allow axial and coronal views to be made. These images must be used to exclude related fractures or injuries, particularly orbital wall fractures. Special radiological methods, such as a dacryocystogram, are not commonly used for primary surgery, because direct examination usually is possible during the operation.

Timing of Treatment

The timing of facial surgery is a difficult problem, especially in cases of nasoethmoid trauma. Delays in treatment can lead to difficulty in repositioning the soft tissues, particularly the canthal ligaments, and in identifying damage to the lacrimal duct system. However, early treatment may be impossible because of other injuries, commonly head injuries. Edema poses significant problems for operating in this region, and delay can allow it to resolve. Many patients with these injuries can be treated at 7 to 10 days, but the earlier surgery can be undertaken, allowing for other injuries and swelling, the more satisfactory.

Anatomy

A thorough understanding of normal anatomy is essential to achieve a satisfactory treatment result. Certain anatomical structures are disproportionately important.

Bony Anatomy

The nose is the most conspicuous feature of the bony skeleton in the nasoethmoid region. The two nasal bones and the vertical midline bony septum form its major structural components. The nasal bones superiorly articulate through a serrated joint with the nasal part of the frontal bone. Laterally, they articulate with the frontal process of the maxilla. Superiorly, the bones are thick; they gradually thin to the notched inferior borders that are continuous with the lateral nasal cartilages. The medial borders are thicker above than below, and the two nasal bones articulate with each other around the midline of the nose. The paired nasal bones have a vertical crest on their posterior surface that forms part of the midline septum of the nose. They articulate with the nasal spine of the frontal bone, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, and the cartilage of the nasal septum from above downward.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses