Intraoral Cameras

Originally purely a discipline geared at eliminating pain, dentistry has evolved into a discipline with many different complex treatment procedures. This change is, to a great extent, due to the longer life expectancy of people (see also: The Future of Dentistry, p. 279). The transition from symptomatic treatments to patient-preferred treatments requires extensive patient education by dentists and their staff. Practices in which there is no active patient education have recorded a decline in treatment activity; this is because of the general decrease in caries activity that has occurred in the population. In contrast, practices that provide extensive patient education have demonstrated fast and impressive growth and an increased use of new treatment techniques.

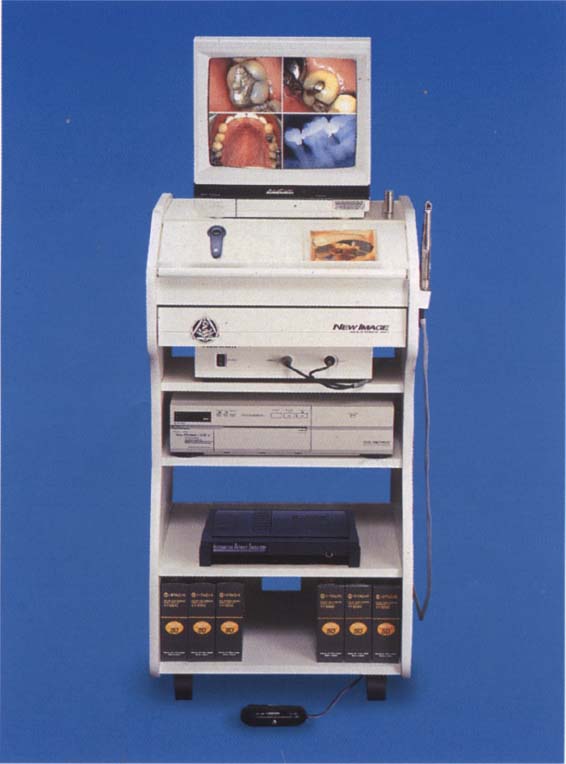

37 Intraoral camera system (e. g., Reveal)

Does not every dentist like to practice state-of-the-art dentistry? For each tooth defect there are various restorative methods that have different prognoses and prices. Therefore, it is important that the dentist shows patients the status quo of their teeth and demonstrates the different treatment options. Intraoral cameras are imperative for these presentations.

Use of Intraoral Cameras

In the late 1950s and the 1960s, different presentation techniques found their way into dental education. Video technology with close-up images was used to demonstrate treatment methods. Nowadays, video technology has become both a teaching and learning tool in all areas of education and training. Numerous training programs—used also in dentistry—are nowadays supported by instructional videos.

Dentists are somewhat restrained in their use of video technology in patient education. A possible reason is that the pain-oriented dentistry practiced earlier, which was primarily therapy-oriented, did not require any detailed patient education. However, because of the changes that have occurred in dentistry, new methods are needed for patient education, including video technology. Since the 1970s, many health-related organizations have developed films targeting patient education. This method of education is meaningful and should be used by all dentists.

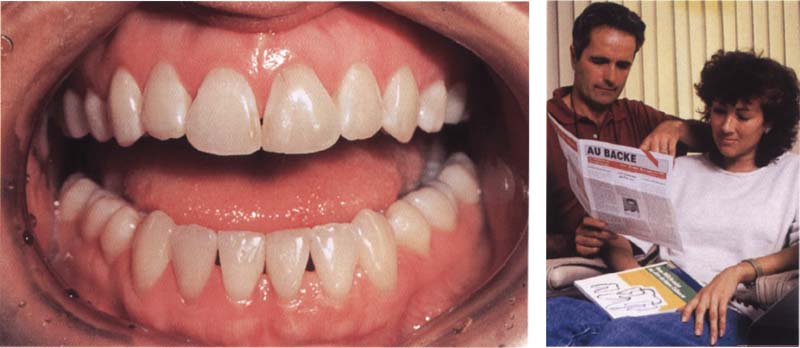

38 Computer-based patient information

A patient wishes to have his/her teeth bleached. One can demonstrate the status quo by means of this picture.

Right: Newsletters are not only brochures for the practice, but are also useful for informing patients about certain treatments or as a marketing tool. However, it must be remembered that brochures distributed by the industry are often of questionable value.

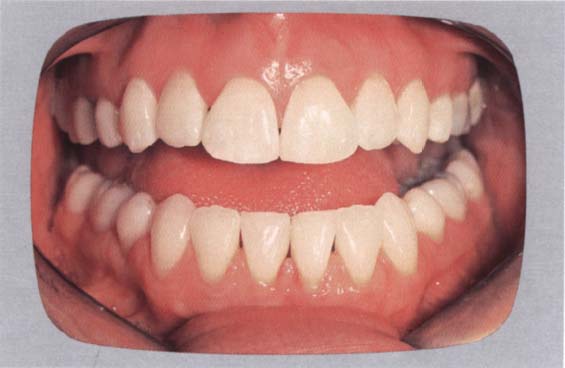

39 Computer-generated simulation of the treatment goal

Tooth color can be brightened on the screen according to the patient’s wishes. The dentist can then determine whether it is possible to do justice to the patient’s ideas using the available methods. If this is not possible, the dentist can demonstrate a more realistic treatment goal to the patient before treatment starts.

In different areas of medicine—particularly in gastroenterology—endoscopes have been used for many years. The first intraoral video camera, the Fuji DentaCam, was developed from these endoscopes in 1987. Even though interest in the camera disappeared soon after its introduction, there were some dentists who realized the potential of intraoral miniature cameras. Since then, many manufacturers have made developments or improvements in intraoral cameras.

Simultaneously, so-called imaging systems were being used in many areas of industry and medicine, with which digital pictures (of houses, cars, faces, etc.) were taken and later processed with the help of a computer. This imaging concept was also introduced into dentistry in the late 1980s and was used to change electronic images of anatomical, oral outlines to be used in treatment planning and in patient education. Although many users assumed that this imaging concept would be an extraordinarily successful method for improved patient education, it has not yet found the acceptance it deserves among users of intraoral cameras.

Patient Education

Dental practices that are equipped with intraoral cameras use them, first and foremost, to show patients their own intraoral images. Video films, watched in the practice or at home, can also be used to promote patient education. These two ways of using video technology predominate in dentistry today.

How Can the Intraoral Camera Be Used to Educate Patients?

Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

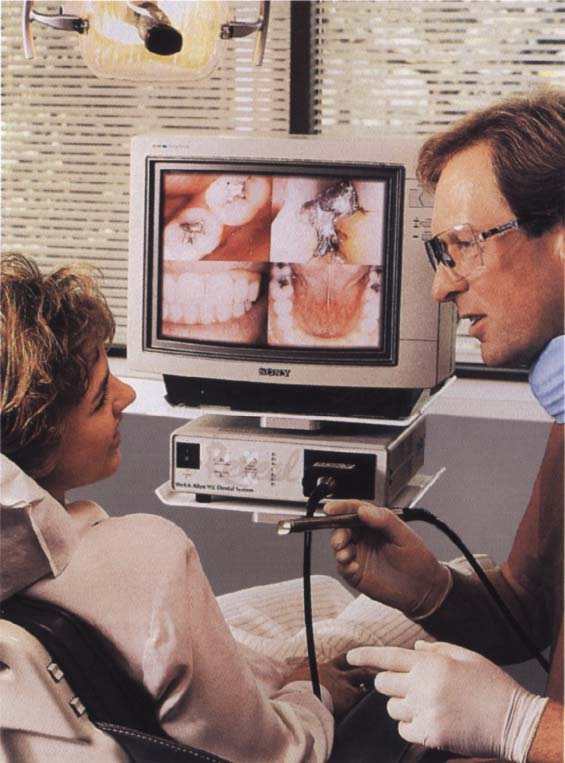

Each dentist uses different methods to modify patient behavior and acceptance of treatment plans. The intraoral camera allows the patient to directly observe the intraoral situation for the first time. Thus, the patient can participate directly in the decision-making process as far as the treatment plan is concerned. The dentist or staff can use an intraoral camera to explain any relevant details to the patient. In a dental office with well-trained staff, patient education is usually performed by the staff. This is cost-saving and, furthermore, the staff are often more thorough than the dentist in presenting the instructional aids.

Intensive patient education with the use of intraoral images is recommended because these images show the necessity of a treatment or a particular, selected treatment method. The intraoral camera is a simple, easy-to-use medium for educational purposes. The areas of the mouth requiring therapeutic measures are shown on the screen situated in front of the patient. This relatively self-explanatory method usually leads to acceptance of the proposed therapy.

A diagnostic session which also uses an intraoral camera takes only a little longer than a regular session. Patients taking advantage of such a diagnostic session alter their behaviour and develop, often spontaneously, an astonishing interest in the condition of their oral health. The advantages for the dentist He in having an increasingly active practice and the introduction of new clinical techniques.

The intraoral camera is used primarily for patient education in the dental practice. The integration of an intraoral camera in the diagnostic session necessitates neither radical administrative changes nor other serious alterations.

40 Intraoral video appliances used chairside

The intraoral video camera and the monitor should be installed close to the dental chair so that they can be used without significant time delays.

Cosmetic Imaging

Imaging methods are used to demonstrate to the patient possible modifications, for example, by means of aesthetic dentistry. Moreover, they open up new possibilities for the dentist in aesthetically-oriented therapy. After images of the oral structures have been made, they can be modified electronically. For example, a diastema can be closed, tooth color can be lightened, the visible gingiva can be increased or reduced, a chin remolded, class-III malocclusions altered, etc. These results can consequently be seen by both the dentist and the patient.

If “before and after” pictures are shown, the computer-processed electronic image becomes particularly impressive for patients and often results in behavioral changes. However, use of intraoral images results in significantly greater changes in the routine of the practice than use of intraoral camera does. More time is required for a diagnostic session. Normally, a separate room must be available, and highly motivated and well-trained staff are needed who have sufficient time and creativity to demonstrate the different therapeutic options to the patient.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses