Dental trauma in childhood and adolescence is common. By 5 years of age, 31% to 40% of boys and 16% to 30% of girls have suffered some dental trauma; by 12 years, these figures are 12% to 33% and 4% to 19%, respectively. Boys are affected almost twice as often as girls in both the primary and permanent dentitions.

Most dental injuries involve the anterior teeth, especially the maxillary central incisors. The mandibular central incisors and maxillary lateral incisors are less frequently involved. Concussion, subluxation, and luxation are the most common injuries in the primary dentition, whereas uncomplicated crown fractures are most common in the permanent teeth.

The most accident-prone ages are between 2 and 4 years for the primary dentition and between 7 and 10 years for the permanent dentition. Coordination and judgment are incompletely developed in young children, and most injuries in the primary dentition are the result of falls in and around the home. In the permanent dentition, most injuries are caused by falls and collisions associated with playing and running, although bicycles are a common accessory. The place of injury varies in different countries according to local customs, but accidents in the schoolyard remain common. Sports injuries usually occur in the teenage years and are commonly associated with contact sports such as soccer, rugby, ice hockey, and basketball. Injuries due to road traffic accidents and assaults are most commonly associated with the late teenage years and adulthood and are often closely related to alcohol abuse. One form of injury in childhood that must never be forgotten is child physical abuse or nonaccidental injury; more than 50% of affected children have orofacial injuries.

The exact mechanisms of dental injuries are largely unknown, and experimental evidence is lacking, but injuries can result from either direct or indirect trauma. Direct trauma occurs when the tooth itself is struck. Indirect trauma is seen when the lower dental arch is forcefully closed against the upper (e.g., by a blow to the chin). Direct trauma implies injury to the anterior region, whereas indirect trauma favors crown or crown-root fractures of the premolars and molars with the possibility of jaw fractures in the condylar regions and in the symphysis. The factors that influence the outcome or type of injury are energy impact, resilience of the impacting object, shape of the impacting object, and angle of direction of the impacting force.

Increased overjet with protrusion of upper incisors and insufficient lip closure are significant predisposing factors to traumatic dental injuries. Injuries are almost twice as frequent among children with protruding incisors, and the number of teeth affected in a particular incident is also greater. The second major group of children with predisposition to traumatic injuries are the accident prone. They sustain repeated trauma to their teeth, with reported frequencies ranging from 4% to 30%.

Classification of DentoAlveolar Injuries

Correct and appropriate treatment demands accurate diagnosis. Table 17-1 summarizes the classification of dento-alveolar injuries based on the World Health Organization (WHO) system.

| Type of Injury | Description |

|---|---|

| Injuries to the Hard Dental Tissues and the Pulp | |

| Enamel infraction | Incomplete (crack) of enamel without loss of tooth substance |

| Enamel fracture | Loss of tooth substance confined to enamel |

| Enamel-dentine fracture | Loss of tooth surface confined to enamel and dentine not involving the pulp |

| Complicated crown fracture | Fracture of enamel and dentine exposing the pulp |

| Uncomplicated crown-root fracture | Fracture of enamel, dentine, and cementum but not involving the pulp |

| Complicated crown-root fracture | Fracture of enamel, dentine, and cementum and exposing the pulp |

| Root fracture | Fracture involving dentine, cementum, and pulp. Can be subclassified into apical, middle, and coronal third |

| Injuries to the Periodontal Tissues | |

| Concussion | No abnormal loosening or displacement but marked reaction to percussion |

| Subluxation (loosening) | Abnormal loosening but no displacement |

| Extrusive luxation (partial avulsion) | Partial displacement of tooth from socket |

| Lateral luxation | Displacement other than axially with comminution or fracture of alveolar socket |

| Intrusive luxation | Displacement into alveolar bone with comminution or fracture of alveolar socket |

| Avulsion | Complete displacement of tooth from socket |

| Injuries to Supporting Bone | |

| Comminution of mandibular or maxillary alveolar socket wall | Crushing and compression of alveolar socket; found in intrusive and lateral luxation injuries |

| Fracture of mandibular or maxillary alveolar socket wall | Fracture confined to facial or lingual/palatal socket wall |

| Fracture of mandibular or maxillary alveolar process | Fracture of the alveolar process that may or may not involve the tooth sockets |

| Fracture of the mandible or maxilla | May or may not involve the alveolar socket |

| Injuries to Gingiva or Oral Mucosa | |

| Laceration of gingiva or oral mucosa | Wound in the mucosa resulting from a tear |

| Contusion of gingiva or oral mucosa | Bruise not accompanied by a break in the mucosa, usually causing submucosal hemorrhage |

| Abrasion of gingiva or oral mucosa | Superficial wound produced by rubbing or scraping of the mucosal surface |

History and Examination

History Specific to DentoAlveolar Injuries

The exact nature of the accident gives information on the type and severity of dentoalveolar injury to be expected. In a minor, a discrepancy between the history and the clinical findings should raise suspicion of child physical abuse or nonaccidental injury.

Lost teeth or fragments should be accounted for. If there is a history of loss of consciousness and teeth or teeth fragments cannot be found, a chest radiograph is essential. Similarly, if there is a soft tissue laceration of the upper or lower lip, anteroposterior and lateral soft tissue views of the lips should be obtained.

The time interval between injury and treatment significantly affects the prognosis for both the pulp and the periodontal ligament (PDL).

A history of previous dentoalveolar trauma can affect pulpal sensibility tests and the recuperative capacity of the pulp and periodontium.

In a minor, a history of previous dentoalveolar trauma could raise suspicion about the possibility of child physical abuse or whether the minor is just accident prone.

Medical History Specific to DentoAlveolar Injuries

Features of the medical history that are relevant to dento-alveolar injuries include the following:

- •

Bleeding disorders: Close liaison with hematologists is crucial if soft tissues are lacerated or teeth are to be removed.

- •

Allergies: Alternative antibiotics need to be prescribed.

- •

Congenital heart disease or rheumatic fever: These are not necessarily contraindications to reimplantation of teeth; however, the advice of the physician should be sought. If endodontic treatment is likely to be difficult or may involve a persistent necrotic focus, then the risk of bacterial endocarditis is significant, and reimplantation may be contraindicated after a risk-versus-benefit analysis.

- •

Severe immunosuppression: This is a contraindication to any procedure that is likely to require prolonged endodontic treatment with a persistent necrotic focus.

- •

Tetanus prophylaxis: This should be checked with the physician. Usually, a tetanus toxoid booster is required if there is soil contamination of a wound and the patient has not been given a tetanus booster in the previous 5 to 10 years.

Extraoral Examination

Severe facial swelling and bruising may indicate underlying bony injury. Lacerations require careful débridement to remove all foreign material before suturing ( Fig. 17-1 ). Antibiotics or tetanus toxoid or both may be required if wounds are contaminated. Limitation of mandibular movement or mandibular deviation on opening or closing of the mouth may indicate a jaw fracture or dislocation.

Intraoral Examination

The intraoral examination must be systematic and should include recording of any laceration, hemorrhage, or swelling of the oral mucosa or gingiva. All lacerations should be cleaned to remove any foreign bodies (see Fig. 17-1 ). Lacerations of the lips or tongue must be sutured, but those of the oral mucosa heal very quickly and may not need suturing. Orofacial signs of child physical abuse may be present (see later discussion). Any abnormalities of occlusion, tooth displacement, fractured crowns, or cracks in the enamel must also be noted.

The following signs and reactions to tests are particularly helpful:

- •

Mobility: Degree of mobility is estimated in a horizontal and a vertical direction. If several teeth move together en bloc, a fracture of the alveolar process should be suspected. Excessive mobility may also suggest root fracture or tooth displacement.

- •

Reaction to percussion: This is tested in a horizontal and a vertical direction and compared against a contralateral uninjured tooth. A duller note may indicate root fracture.

- •

Color of tooth: Early color change is visible on the palatal surface of the gingival third of the crown.

- •

Reaction to sensibility tests: Thermal tests with warm gutta percha or ethyl chloride are widely used. However, an electrical pulp tester in the hands of an experienced operator is more reliable. Nevertheless, vitality testing, especially in children, is notoriously unreliable and should never be assessed in isolation from the other clinical and radiographic data. Neither negative nor positive responses should be trusted immediately after trauma. A positive response does not rule out later pulpal necrosis, and although a negative response suggests pulpal damage, it does not necessarily indicate a necrotic pulp. The negative reaction is often caused by a shockwave effect that has damaged the apical nerve supply. The pulp in such cases may have a normal blood supply. In all vitality testing, the reaction of uninjured contralateral teeth should be included and documented for comparison. In addition, all teeth adjacent to the obviously injured teeth should be regularly assessed, because they have probably suffered concussion injury. In the future, advances in Doppler technology will allow the clinician to measure whether the vascular supply to individual teeth is intact. Doppler probes are currently too expensive for the general dental practitioner, but research has shown them to be a reliable tool.

Radiographic Examination

Three types of radiograph allow the clinician to accurately diagnose and treat all dentoalveolar injuries:

- •

Periapical: Reproducible periapical projections made with the long cone technique are best for accurate diagnosis and clinical audit. Two radiographs at different angles may be essential to detect a root fracture. However, if access and cooperation are difficult, one anterior occlusal radiograph rarely misses a root fracture. A small periapical film placed inside the upper or lower lip will detect tooth fragments or foreign bodies in the vertical plane.

- •

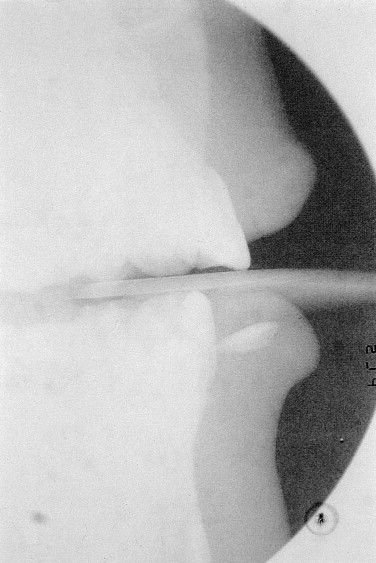

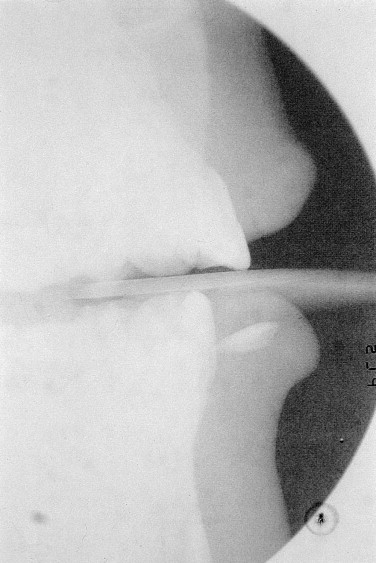

Occlusal: This projection can detect root fractures and displacements when the mouth cannot open enough to accommodate a periapical film. An occlusal film held by the patient or by a helper at the side of the mouth can be used to detect tooth fragments or foreign bodies in the lateral plane ( Fig. 17-2 ).

FIGURE 17-2 Tooth fragment from an upper incisor is lodged in the lower lip. - •

Dental panoramic tomograph: This is essential in all dento-alveolar trauma cases and may detect an unsuspected underlying bony injury.

Photographic Examination

Good clinical photographs are useful to assess treatment outcomes and for medicolegal purposes.

History and Examination

History Specific to DentoAlveolar Injuries

The exact nature of the accident gives information on the type and severity of dentoalveolar injury to be expected. In a minor, a discrepancy between the history and the clinical findings should raise suspicion of child physical abuse or nonaccidental injury.

Lost teeth or fragments should be accounted for. If there is a history of loss of consciousness and teeth or teeth fragments cannot be found, a chest radiograph is essential. Similarly, if there is a soft tissue laceration of the upper or lower lip, anteroposterior and lateral soft tissue views of the lips should be obtained.

The time interval between injury and treatment significantly affects the prognosis for both the pulp and the periodontal ligament (PDL).

A history of previous dentoalveolar trauma can affect pulpal sensibility tests and the recuperative capacity of the pulp and periodontium.

In a minor, a history of previous dentoalveolar trauma could raise suspicion about the possibility of child physical abuse or whether the minor is just accident prone.

Medical History Specific to DentoAlveolar Injuries

Features of the medical history that are relevant to dento-alveolar injuries include the following:

- •

Bleeding disorders: Close liaison with hematologists is crucial if soft tissues are lacerated or teeth are to be removed.

- •

Allergies: Alternative antibiotics need to be prescribed.

- •

Congenital heart disease or rheumatic fever: These are not necessarily contraindications to reimplantation of teeth; however, the advice of the physician should be sought. If endodontic treatment is likely to be difficult or may involve a persistent necrotic focus, then the risk of bacterial endocarditis is significant, and reimplantation may be contraindicated after a risk-versus-benefit analysis.

- •

Severe immunosuppression: This is a contraindication to any procedure that is likely to require prolonged endodontic treatment with a persistent necrotic focus.

- •

Tetanus prophylaxis: This should be checked with the physician. Usually, a tetanus toxoid booster is required if there is soil contamination of a wound and the patient has not been given a tetanus booster in the previous 5 to 10 years.

Extraoral Examination

Severe facial swelling and bruising may indicate underlying bony injury. Lacerations require careful débridement to remove all foreign material before suturing ( Fig. 17-1 ). Antibiotics or tetanus toxoid or both may be required if wounds are contaminated. Limitation of mandibular movement or mandibular deviation on opening or closing of the mouth may indicate a jaw fracture or dislocation.

Intraoral Examination

The intraoral examination must be systematic and should include recording of any laceration, hemorrhage, or swelling of the oral mucosa or gingiva. All lacerations should be cleaned to remove any foreign bodies (see Fig. 17-1 ). Lacerations of the lips or tongue must be sutured, but those of the oral mucosa heal very quickly and may not need suturing. Orofacial signs of child physical abuse may be present (see later discussion). Any abnormalities of occlusion, tooth displacement, fractured crowns, or cracks in the enamel must also be noted.

The following signs and reactions to tests are particularly helpful:

- •

Mobility: Degree of mobility is estimated in a horizontal and a vertical direction. If several teeth move together en bloc, a fracture of the alveolar process should be suspected. Excessive mobility may also suggest root fracture or tooth displacement.

- •

Reaction to percussion: This is tested in a horizontal and a vertical direction and compared against a contralateral uninjured tooth. A duller note may indicate root fracture.

- •

Color of tooth: Early color change is visible on the palatal surface of the gingival third of the crown.

- •

Reaction to sensibility tests: Thermal tests with warm gutta percha or ethyl chloride are widely used. However, an electrical pulp tester in the hands of an experienced operator is more reliable. Nevertheless, vitality testing, especially in children, is notoriously unreliable and should never be assessed in isolation from the other clinical and radiographic data. Neither negative nor positive responses should be trusted immediately after trauma. A positive response does not rule out later pulpal necrosis, and although a negative response suggests pulpal damage, it does not necessarily indicate a necrotic pulp. The negative reaction is often caused by a shockwave effect that has damaged the apical nerve supply. The pulp in such cases may have a normal blood supply. In all vitality testing, the reaction of uninjured contralateral teeth should be included and documented for comparison. In addition, all teeth adjacent to the obviously injured teeth should be regularly assessed, because they have probably suffered concussion injury. In the future, advances in Doppler technology will allow the clinician to measure whether the vascular supply to individual teeth is intact. Doppler probes are currently too expensive for the general dental practitioner, but research has shown them to be a reliable tool.

Radiographic Examination

Three types of radiograph allow the clinician to accurately diagnose and treat all dentoalveolar injuries:

- •

Periapical: Reproducible periapical projections made with the long cone technique are best for accurate diagnosis and clinical audit. Two radiographs at different angles may be essential to detect a root fracture. However, if access and cooperation are difficult, one anterior occlusal radiograph rarely misses a root fracture. A small periapical film placed inside the upper or lower lip will detect tooth fragments or foreign bodies in the vertical plane.

- •

Occlusal: This projection can detect root fractures and displacements when the mouth cannot open enough to accommodate a periapical film. An occlusal film held by the patient or by a helper at the side of the mouth can be used to detect tooth fragments or foreign bodies in the lateral plane ( Fig. 17-2 ).

FIGURE 17-2 Tooth fragment from an upper incisor is lodged in the lower lip. - •

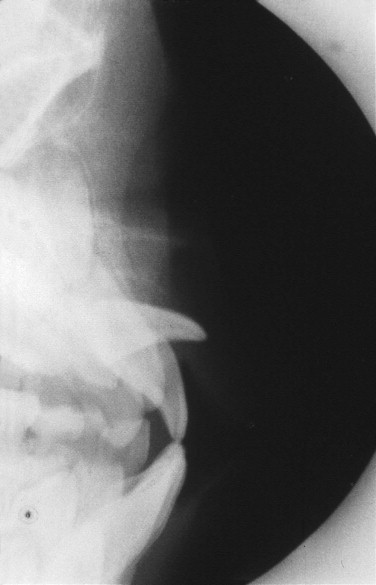

Dental panoramic tomograph: This is essential in all dento-alveolar trauma cases and may detect an unsuspected underlying bony injury.

Photographic Examination

Good clinical photographs are useful to assess treatment outcomes and for medicolegal purposes.

State-of-the-Art Management of Injuries to the Primary Dentition

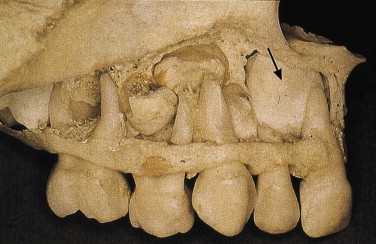

During its early development, the permanent incisor is located palatally to the apex of the primary incisor and in close proximity to it. With any injury to a primary tooth, there is a risk of damage to the underlying permanent successor ( Fig. 17-3 ). Parents should be advised that in all cases of trauma involving the primary dentition, there is a 50% chance of developmental disturbances to the permanent successor teeth.

Children aged 2 to 4 years are most likely to injure their primary dentition. Realistically, this means that few restorative procedures are possible; in most cases, the decision is between extraction or maintenance without extensive treatment. A primary incisor should always be removed if its maintenance would jeopardize the developing tooth bud.

A traumatized primary tooth that is retained should be assessed regularly for clinical and radiographic signs of pulpal or periodontal complications. Radiographs may even detect damage to the permanent successor. Soft tissue injuries in children should be assessed weekly until healed. Tooth injuries should be reviewed every 3 to 4 months for the first year and then annually until the primary tooth exfoliates and the permanent successor is in place.

Uncomplicated Crown Fracture

In cases of uncomplicated crown fracture, the sharp edges should be smoothed or the crown morphology restored with a bonded restoration if cooperation allows.

Complicated Crown Fracture

In complicated crown fracture, pulp extirpation, root canal obturation with resorbable zinc oxide cement, and a bonded restoration to restore crown morphology can be achieved with reasonable cooperation. However, in many cases, extraction of the tooth is the only realistic option.

Crown-Root Fracture

In crown-root fractures, the pulp is invariably exposed and the fracture line extends well below the gingival margin. Restorative treatment is extremely difficult, and the tooth is best extracted.

Root Fracture

In cases of root fracture without displacement and with only a small amount of mobility, the tooth should be kept under observation. If the coronal fragment becomes nonvital and symptomatic, it should be removed. The apical portion usually remains vital and undergoes resorption. If there is marked displacement and mobility, only the coronal portion should be removed. Unnecessary searching for small apical root fragments runs the risk of iatrogenic damage to the permanent successor tooth.

Concussion, Subluxation, and Luxation Injuries

In all instances, associated soft tissue damage should be cleaned by the parent twice daily with 0.2% chlorhexidine solution using cotton buds or gauze swabs until healing occurs.

- •

Concussion : These injuries require periodic review with close observation for signs of nonvitality.

- •

Subluxation : If there is slight mobility, parents should be advised to keep the traumatized area as clean as possible and to give the child a soft diet for 1 to 2 weeks.

- •

Extrusive luxation : These teeth are usually very mobile and require extraction.

- •

Lateral luxation : If the crown is displaced palatally, the apex moves buccally, away from the permanent teeth germ. If the occlusion is not gagged, conservative treatment to await some spontaneous realignment is possible. If the crown is displaced buccally, the apex will be displaced toward the permanent tooth bud, and extraction is indicated to minimize further damage to the permanent successor.

- •

Intrusive luxation : This is a common injury. The aim of investigation is to establish the direction of displacement by thorough radiographic examination. If the root is displaced palatally toward the permanent successor, the primary tooth should be extracted to minimize possible damage to the developing permanent successor. If the root is displaced buccally, periodic review to monitor spontaneous reeruption should be undertaken. Review should be weekly for 1 month, then monthly for a maximum of 6 months. Most reeruption occurs between 1 and 6 months. If reeruption does not occur, ankylosis is likely, and extraction is necessary to prevent ectopic eruption of the permanent successor.

- •

Exarticulation (avulsion): Replantation of avulsed primary incisors is not recommended because of the risk of damage to the permanent tooth germs. Space maintenance is not necessary after loss of a primary incisor, because only minor drifting of adjacent teeth occurs. The eruption of the permanent successor may be delayed for about 1 year as a result of abnormal thickening of connective tissue overlying the tooth germ.

Injuries to Supporting Bone

Most fractures of the alveolar socket in primary dentition do not require splinting, because bony healing is rapid in small children. Jaw fractures are treated in the conventional manner, although stabilization after reduction may be difficult due to lack of sufficient teeth.

State-of-the-Art Management of Sequelae of Injuries to the Primary Dentition

Pulpal Necrosis

Necrosis is the most common complication of primary trauma. Evaluation is based on tooth color and radiographic findings. Vitality testing is unreliable and of no clinical benefit in primary teeth. Teeth of a normal color rarely develop periapical inflammation, and mildly discolored teeth also may be vital. A mild gray color occurring soon after trauma may represent intrapulpal bleeding with a pulp that is still vital. This color may recede, but if it persists, necrosis should be suspected. Radiographic examination should be scheduled every 3 months to check for periapical inflammation. Failure of the pulp cavity to reduce in size is an indicator of pulp death. Teeth should be extracted whenever there is evidence of periapical inflammation, to prevent possible damage to the permanent successor.

Pulpal Obliteration

Obliteration of the pulp chamber and canal is a common reaction to trauma. Clinically, the tooth becomes yellow or opaque. Normal exfoliation is usual, but occasionally periapical inflammation develops and extraction is required. Annual periapical radiography is advisable to detect infection and to check physiological root resorption. If resorption does not occur, the permanent successor will erupt in an ectopic position.

Root Resorption

Internal resorption may be seen with concussion, subluxation, and luxation injuries and in external inflammatory resorption with intrusive injuries. Extraction is usually the preferred treatment for these types of root resorption.

Injuries to Developing Permanent Teeth

Injury to the permanent successor tooth can be expected in 12% to 69% of cases of primary tooth trauma and in 19% to 68% of jaw fracture. Intrusive luxation causes most disturbances. Avulsion of a primary incisor also causes damage if the apex moved toward the permanent tooth bud before the avulsion. Most damage to the permanent tooth bud occurs before 3 years of age, during its developmental stage. However, the type and severity of disturbance are closely related to the age at the time of injury. Changes in the morphology and mineralization of the crown of the permanent incisor are most common, but later injuries can cause radicular anomalies.

Injuries to developing teeth can be classified as follows:

- •

White or yellow-brown discoloration of enamel—injury at 2 to 7 years of age

- •

White or yellow-brown discoloration of enamel with circular enamel hypoplasia—injury at 2 to 7 years of age

- •

Crown dilacerations ( Fig. 17-4 )—injury at about 2 years of age

FIGURE 17-4 Dilaceration of an upper permanent central incisor resulting from an intrusion injury to the primary incisor at the age of 2 years. - •

Odontoma-like malformation—injury before 1 to 3 years of age

- •

Root duplication—injury at 2 to 5 years of age

- •

Vestibular or lateral root angulation and dilaceration—injury at 2 to 5 years of age

- •

Partial or complete arrest of root formation—injury at 5 to 7 years of age

- •

Sequestration of permanent tooth germs

- •

Disturbance in eruption

The term dilaceration describes an abrupt deviation of the long axis of the crown or root portion of the tooth. This deviation results from a traumatic nonaxial displacement of already formed hard tissue in relation to developing soft tissue.

The term angulation describes a curvature of the root that results from gradual change in the direction of root development without evidence of abrupt displacement of the tooth germ during odontogenesis. This may be vestibular (i.e., labiopalatal) or lateral (i.e., mesiodistal). Evaluation of the full extent of complications after injuries must await complete eruption of all permanent teeth involved. However, most serious sequelae (disturbances in tooth morphology) can be diagnosed radiographically within the first year after the trauma.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses