The Maintenance Phase of Care

After completion of definitive phase therapy there will be remaining issues that must be addressed and rendered treatment that must be reevaluated. Some of these concerns will need attention for as long as the dentist-patient therapeutic relationship exists. In addition to their importance to patient care, good maintenance phase plans provide the patient-specific elements essential to the development of an organized, practicewide system of periodic care that serves as the backbone of a successful and productive dental practice.

Although this aspect of the treatment plan may seem less important at the outset, the maintenance phase represents a critical component of any complex treatment plan. In many cases, the long-term success or failure of the plan depends on it. As this chapter unfolds, it will become clear why the dentist should discuss long-term periodic care with the comprehensive care patient. Furthermore the rationale for initiating this discussion when the original treatment plan is presented will also become apparent.

Prevention of future problems is, of course, the guiding principle of the maintenance phase. The astute practitioner works throughout all phases of treatment to educate the patient in strategies for maintaining a healthy oral condition and preventing future oral disease. Certain aspects of a systemic phase may include activities that are preventive in nature. The acute phase may include treatment that has the effect of preventing disease progression. The disease control phase, by its nature, is preventive in orientation, and numerous references to preventive therapies are made in Chapter 7. Nevertheless, significant patient education and the reinforcement of earlier oral hygiene instruction occur primarily during maintenance phase visits. For that reason, preventive concepts and preventive therapy are emphasized in this chapter. The reader is reminded that it would be shortsighted and inappropriate for the practitioner to make prevention primarily the hygienist’s responsibility and to attend to it exclusively in the maintenance phase. Prevention must be the responsibility of the entire dental team and must be carried out throughout the treatment process.

The maintenance phase must be flexible and individualized, with timing and content specifically tailored to each patient’s needs. Although formulated at the treatment planning stage, it will have been modified during the disease control and definitive treatment phases, and will take its final form at the posttreatment assessment, which is discussed in the following section. The dentist implements maintenance phase care through the periodic visit discussed in the final section of this chapter. The term periodic visit or recare visit is preferred to recall visit, which suggests that something is defective and needs to be corrected. In contrast, maintenance services should by their very nature be timed and directed to accommodate the individual patient’s needs. The American Dental Association (ADA) sanctioned procedure coding system uses the designation “Periodic Oral Evaluation.” Consistent with that perspective, the terms “periodic examination” and “periodic visit” are used in this text.

POSTTREATMENT ASSESSMENT

The posttreatment assessment is a dedicated, structured appointment scheduled at the conclusion of the disease control phase of treatment, if the original plan includes disease control, and at the conclusion of the definitive phase. The purposes of the appointment are to assess the patient’s response to treatment, comprehensively evaluate current oral health status, determine any new treatment needs, and develop a specific plan for future treatment. If accomplished during the first periodic evaluation and visit, the posttreatment assessment includes oral health instruction, selected scaling, and oral prophylaxis.

Most colleges of dentistry have developed a formalized process for a clinical examination when the patient is about to exit the patient care program. This discussion uses one such system as an example. Because each practice or institution has unique needs, the decision regarding development of a posttreatment assessment protocol is made on an individual basis. Whatever mechanism the dentist decides on, the emphasis here is on the importance of engaging the patient in a comprehensive reevaluation and reassessment at the conclusion of the disease control phase of treatment and/or at the conclusion of the entire plan of care. Many practitioners prefer not to formalize this process, declining to take the time to develop a specific protocol or form for recording findings. Certainly the current standard of care in practice does not dictate a mandatory posttreatment assessment protocol. The standard of care does require, however, that patients be provided maintenance services and continuity of care. In that context, the concepts described here should have application to any practice. Each practitioner is encouraged to incorporate some type of patient maintenance program into the office policy manual and to implement use of that program with each patient. If the reader does choose to develop a formal posttreatment assessment protocol, the information included here can be used as a guide for that purpose.

Objectives for the Posttreatment Assessment

The purpose and intent of the posttreatment assessment is to enable the practitioner to evaluate the following:

The posttreatment assessment provides a foundation for planning any additional treatment and maintenance therapy the patient will need.

Elements of the Posttreatment Assessment

Items to be included in the posttreatment assessment and recorded in the patient record vary with the nature and scope of the dental practice, the individual patient profile, and need. Typical elements in a posttreatment assessment are as follows:

Documenting the Posttreatment Assessment

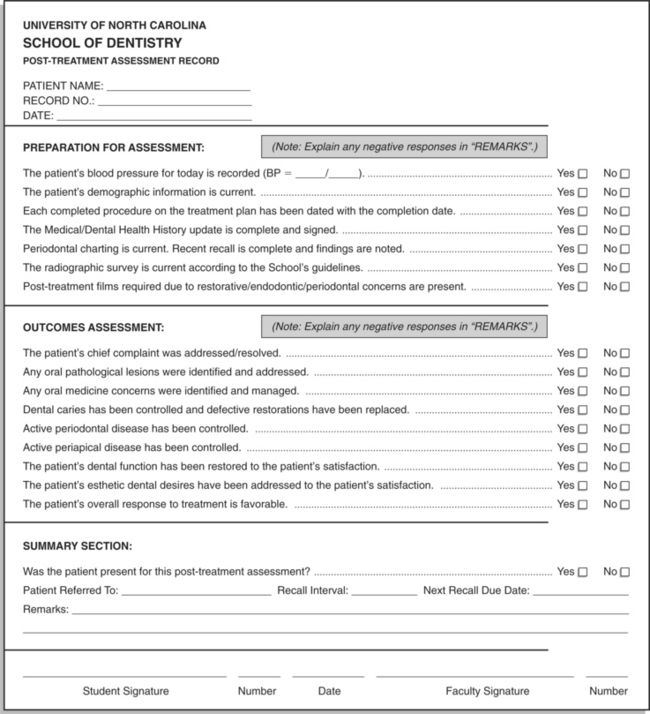

The posttreatment assessment may be documented in the progress notes in a narrative or bullet format, with or without a predetermined outline to guide the process. If the practice has multiple providers, a common outline or format should be developed for consistency and efficiency. In an institutional setting, it is usually advantageous to develop a form specifically for that purpose (Figure 9-1).

RATIONALE FOR INCLUDING A MAINTENANCE PHASE IN THE TREATMENT PLAN

The primary purpose of the maintenance phase is to ensure long-term oral health, optimum function, and favorable esthetics for the patient. In the maintenance phase, continuing systemic issues can be managed; disease control measures can be reevaluated and strengthened; and restorations and prostheses can be repaired, cleaned, polished, recontoured, or relined as needed. Success or failure of previous treatment must be reassessed and any necessary additional treatment planned. Multiple benefits derive from a comprehensive and strategically crafted plan for the maintenance phase. These benefits can be clustered into three categories: (1) issues that remain unresolved at the close of the definitive phase of treatment, (2) patient-based issues, and (3) practice management issues.

Unresolved Issues

Follow-up of Untreated Diagnoses

At the conclusion of the definitive treatment phase, previously diagnosed but untreated conditions may require reevaluation. These might include reactive soft tissue lesions, asymptomatic chronic bone lesions, defective but not problematic restorations, or teeth with potential carious lesions. The maintenance phase provides an ideal time to reassess these issues, discuss them with the patient, and develop consensus for a long-term strategy that addresses these issues.

Monitoring Chronic Conditions That Can Affect Oral Health

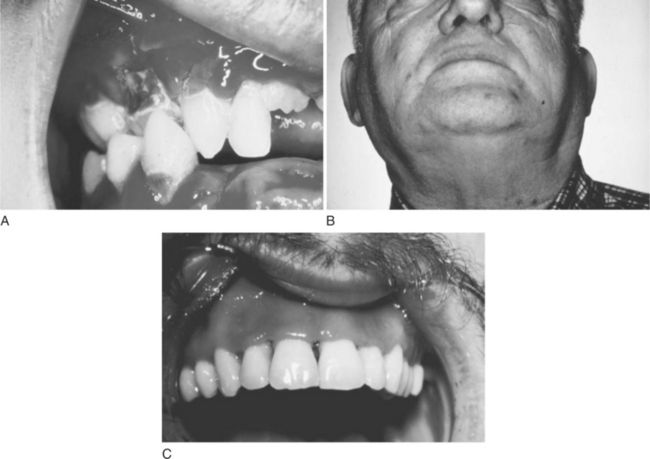

Such conditions might include chronic oral disseases such as periodontal disease; systemic diseases with significant oral manifestations such as Sjögren’s syndrome (Figure 9-2); or systemic diseases that influence plans for or the delivery of dental treatment. The maintenance phase provides an opportunity to reassess these conditions, determine if new intervention or re-treatment is warranted, and deal with any new sequelae or related conditions that have arisen.

Revisiting Elective Treatment Issues

Earlier in the course of treatment, patients may have had dental concerns or aspirations that for many reasons (including time, finances, or anxiety) they chose to defer. Similarly, the patient earlier may have declined certain elective treatments that the dentist recommended, such as removal of asymptomatic third molars or replacement of missing teeth. The maintenance phase provides an ideal opportunity to revisit these issues.

Patient-Based Issues

Rapport Building

Patients return to their dentists for periodic care for many reasons beyond the obvious recommended scaling and oral prophylaxis. The importance of the professional trust and faith that patients place in their dentists and the personal security obtained from the relationship should not be underestimated or taken for granted. Consciously or unconsciously, most patients have a strong expectation that their dentist is diligently looking out for their best interests and will do what is best to promote and ensure their oral health. Periodic visits do much to cement the relationship and fulfill the patient’s expectations.

Patient Education

The maintenance phase serves as an effective instrument to educate and motivate the patient, and helps maintain the patient’s awareness of the importance of continuing attention to oral health. As the dentist plans the maintenance phase and shares that information with the patient, the patient has the opportunity to learn about the nature and the importance of this aspect of the plan of care and to raise questions about it. As the dentist explains the need for maintenance therapy and the ways in which the periodic visits form an integrated part of the overall plan of care, the patient comes to appreciate how this phase of treatment affects his or her future oral health.

More specifically, discussing the maintenance phase helps educate the patient about the details of care provided during the periodic visits and the patient’s own contribution to maintaining a healthy oral condition. This is the ideal opportunity to inform the patient about oral self-care practices that help preserve restorations and prostheses, maintain a disease-free environment, and prevent future problems. Suggestions to the patient may be given orally, in written form, or using pamphlets or audiovisual materials.

Writing the maintenance phase into the treatment plan reminds the patient of its presence and importance each time he or she picks up a copy of the plan of care. It also reminds the patient of specific tasks and expectations that are his or her responsibility. That knowledge becomes a powerful tool for the dentist in ongoing attempts to instill a sense of responsibility in the patient and to reinforce the patient’s appreciation of the need to maintain a long-term therapeutic relationship.

Emphasis on Individualized Care

Although patients may be unsophisticated in their understanding of dental disease or the finer elements of dental treatment, they quickly develop a sense of how a dental practice functions and share that information with their friends and neighbors. Patients may more easily characterize office policy concerning periodic visits than the dentist can. Is the standard a routine “6 months’ checkup and cleaning”? Or is there an individually planned interval with a specified structure tailored to the needs of the individual patient? In the all-too-common first situation, patients may gain the impression that production rather than individualized patient care is the motivating influence.

Arguably one of the greatest rewards in dentistry comes from the satisfaction of seeing long-term patients maintain a healthy, esthetic, and functional oral condition. For the dentist, recognizing his or her role in that process and the patient’s appreciation of that role are rich rewards. These same patients are the best referral sources and can ensure that the practice is sustained for as long as the dentist wishes it to be. Taking the time to develop and carry out a comprehensive and individualized maintenance phase for each patient ensures good patient care. It also can provide enormous benefits to staff, the practice, and the dentist.

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Unfortunately, some patients only think of seeing the dentist when a problem develops. Because the well-constructed maintenance phase places the emphasis on promoting and sustaining optimal oral health and function, rather than on the restoration and reconstruction resulting from past disease, this phase makes clear the role of dentistry as a health care profession.

Anticipating Further Treatment Needs

A thoughtful, comprehensive maintenance phase plan includes any issues that realistically can be expected to need reevaluation, reconsideration, or re-treatment in the future. Specific notes, such as “reevaluate tooth #29 with poor periodontal prognosis” or “reassess patient need and/or desire for crown on tooth #19 with compromised cusp integrity,” confirm that the patient has been alerted to the possible risks and hazards and clearly puts the responsibility for accepting the consequences of deferring treatment on the patient rather than the dentist. A casual review of the original treatment plan (or progress note if written there) quickly brings the issue to the patient’s attention again.

Without a clearly stated maintenance phase, patients may assume that any new problems that arise are at least in part the responsibility of the dentist. The tooth with long-standing severe periodontitis that now must be extracted or the tooth with a large amalgam restoration that now fractures are examples. Recording these potential problems in the treatment plan and calling them to the patient’s attention at the outset of the maintenance phase avoids any potential for doubt, misunderstanding, mistrust, or conflict.

Practice Management Issues

Professional Competence

Collectively the entire patient record if it includes a comprehensive, accurate, and complete database, diagnosis, plan of care, and consent provides excellent evidence of professional competence. A thorough, well-written maintenance phase, although not indispensable in this regard, certainly contributes to a positive view of professional competence and may help discourage a disgruntled patient from pursuing litigation.

Efficient Delivery of Care

A well-written maintenance phase plan of care can be used as an effective tool to alert office staff, dental assistants, hygienists, and the dentist to the particular systemic or oral health issues or other concerns that should be addressed during periodic visits. Awareness of those issues at the outset makes the visit more focused, efficient, and personalized. The patient’s individual needs can be considered immediately without requiring the dentist to sort through the chart, looking at multiple progress notes to reconstruct the history. With a recorded plan, the entire staff approaches the periodic visit proactively, confidently, and efficiently.

Reducing Patient Emergencies

An informed patient who expects and anticipates problems is more likely to take preventive action before a crisis develops, is less likely to need emergency care, is more apt to have a realistic understanding of a problem (and be able to discuss it rationally), and is more apt to accept recommended treatment. For the dentist and the staff, this translates into fewer interruptions, less anxiety for the patient, reduced staff stress, and smoother patient flow. Such a practice usually provides a more patient-friendly, enjoyable, and rewarding setting in which to work.

Partnering With Patients

The maintenance plan encourages the patient to become a partner in the long-term management of his or her oral health, rather than simply a consumer of dental goods and services. The maintenance phase, by design and necessity, engages the patient in the process. Although many patients remain quite comfortable in the traditional model of dental care in which the dentist makes all the decisions, such an approach places all the responsibility for the success of treatment on the shoulders of the dentist, fostering an overly dependent patient-dentist relationship. The maintenance phase provides an effective way to appropriately delineate roles and responsibilities for the patient’s long-term oral health.

ISSUES TYPICALLY INCLUDED IN THE MAINTENANCE PHASE

To list all the items that could be included in the maintenance phase would be a large undertaking. To give the reader a realistic perspective on this issue, the authors suggest the following list of categories that might be included. The list is not all-inclusive, but is representative and may serve as a menu or template from which each practitioner may begin to develop a selection list appropriate for his or her own practice. Although no individual patient would be expected to require attention to all of the areas listed here, it can be anticipated that most patients will need several.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses