Management of cleft lip and cleft palate patients

The management of patients with cleft lip and cleft palate requires prolonged orthodontic treatment and an interdisciplinary approach in providing these patients with optimal aesthetics, function and stability. This chapter describes current concepts and principles in the treatment of patients with cleft lip and palate. Orthodontic or orthopaedic management in infancy, in early mixed dentition, in early permanent dentition and after the completion of facial growth will be discussed. The focus of this chapter will be on the interdisciplinary approach to treatment planning and treatment sequencing.

Cleft lip and palate are the most frequently occurring congenital anomalies. Depending on the extent of the cleft defect, patients may have complex problems dealing with facial appearance, feeding, airway, hearing and speech. Patients with cleft lip and palate are ideally treated in a multidisciplinary team setting involving specialties from the following disciplines: paediatrics, plastic and reconstructive surgery, orthodontics, genetics, social work, nursing, ENT, speech therapy, maxillofacial surgery, paediatric dentistry, prosthetic dentistry and psychology. The orthodontic treatment of patients with clefts is extensive, initiating at birth and continuing into adulthood until the completion of craniofacial skeletal growth. The role of the orthodontist in timing and sequence of treatment is important in terms of overall team management. The goal for complete rehabilitation of patients with clefts is to maximize treatment outcome with minimal intervention. This chapter presents current orthodontic treatment concepts for the management of patients with clefts.

Role of the Orthodontist

In a patient with cleft lip and palate, the malocclusion can be related to soft tissue, skeletal or dental defects. Some cleft orthodontic problems are directly related to the cleft deformity itself, such as discontinuity of the alveolar process and missing or malformed teeth. Some aspects of the malocclusion are secondary to the surgical intervention performed to repair the lip, nose, alveolar and palatal defects. The malocclusion may exist in all the three planes of space: anteroposterior, transverse and vertical. The malocclusion may reflect the severity of the initial cleft deformity and the growth response to the primary surgery. As malocclusion in patients with clefts is often a growth-related problem, the effect of the cleft deformity and primary surgery will be observed throughout the growth of the child until skeletal maturity. The orthodontist must make critical decisions for orthodontic intervention at the appropriate time and prioritize treatment goals for each intervention. For the purpose of organization, the orthodontic treatment of patients with clefts will be presented in four distinct treatment phases: infancy, primary dentition, mixed dentition and permanent dentition.

Infancy

Presurgical infant orthopaedics has been used in the treatment of cleft lip and palate patients for centuries. The early techniques were focused on elastic retraction of the protruding premaxilla followed by stabilization after surgical repair. There still exists a debate on the long-term benefits of presurgical infant orthopaedics, and abundant literature has been published presenting various sides of this story.

The modern school of presurgical orthopaedic treatment in cleft lip and palate was started by McNeil in 1950. Burstone further developed and popularized McNeil’s technique. In 1975, Georgiad and Latham introduced a pinretained active appliance to simultaneously retract the premaxilla and expand the posterior segments over a period of several days. Hotz in 1987 described the use of a passive orthopaedic plate to slowly align the cleft segments. In 1993, Grayson et al1 described a new technique, nasoalveolar molding (NAM), to presurgically mold the alveolus, lip and nose in infants born with cleft lip and palate. The NAM appliance consists of an intraoral molding plate with nasal stents to mold the alveolar ridge and nasal cartilage concurrently. The objective of presurgical NAM is to reduce the severity of the original cleft and nasal and alveolar deformities and thereby enable the surgeon to achieve a better primary repair of the lip and nose. The NAM technique has been shown to significantly improve the surgical outcome of primary repair in cleft lip and palate patients compared with other techniques of presurgical orthopaedics.

Impression technique, appliance fabrication and design

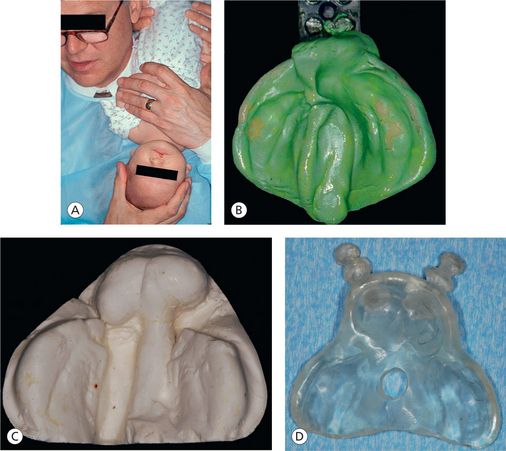

The initial impression of the infant with cleft lip and palate is obtained within the first week of birth using a heavy body silicone impression material. The impression must be taken in a clinical setting that is prepared to handle an airway emergency and in the presence of a surgeon. The molding plate is made of hard, clear, self-cure acrylic that is 2–3 mm in thickness to provide structural integrity and to permit adjustments during the process of molding. A retention button is fabricated and positioned anteriorly at an angle of approximately 40° to the plate (Fig 9.1A–D). The nasal stent is not fabricated at this time. Instead, its construction is delayed until the cleft of the alveolus is reduced to approximately 5–6 mm in width.

Figure 9.1 (A) Infant held in inverted position during the impression process to prevent the tongue from falling back and to allow fluids to drain out. (B) Impression of a unilateral cleft patient using custom tray and heavy body silicone impression material. (C) Plaster stone working model of a bilateral cleft patient for appliance fabrication. (D) Bilateral nasoalveolar molding plate with retention buttons fabricated using self-cure acrylic resin.

Appliance insertion and taping

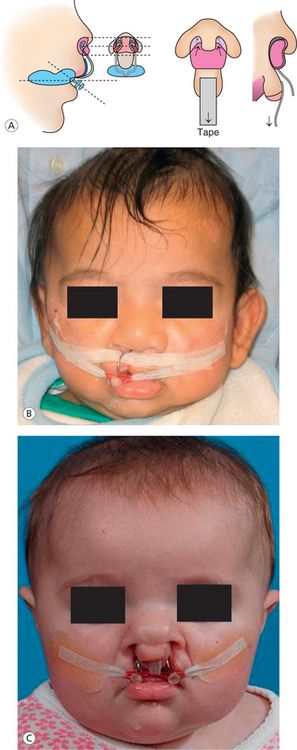

The appliance is then secured extraorally to the cheeks and bilaterally by surgical tapes that have orthodontic elastic bands at one end. The use of skin barrier tapes on the cheeks like DuoDerm or Tegaderm is advocated to reduce irritation on the cheeks. The horizontal surgical tapes are one-quarter inch (0.25”) in width and approximately 3–4” in length. The elastic on the surgical tape is actively engaged on the retention button of the molding plate, and the tape is secured to the cheeks (Fig 9.2). Parents are instructed to keep the plate in the mouth full time and to remove it for daily cleaning. The infant may require time to adjust to feeding with the NAM appliance in the first few days.

Appliance adjustments and nasal stent fabrication

The baby is seen weekly to make adjustments to the molding plate to bring the alveolar segments together. These adjustments are made by selectively removing the hard acrylic and adding soft denture base material to the molding plate. No more than 1 mm of modification of the molding plate should be made at one visit. The nasal stent component of the NAM appliance is incorporated when the width of the alveolar gap is reduced to approximately 5 mm. The stent is made of 0.36” round stainless steel wire and takes the shape of a ‘swan neck’. The intranasal hard acrylic component is shaped into a bilobed form that resembles a kidney, and a layer of soft denture liner is added to the hard acrylic for comfort. The upper lobe enters the nose and gently projects forward the dome, and the lower lobe of the stent lifts the nostril apex and defines the top of the columella (Fig 9.3A–C).

Figure 9.3 (A) Figure showing the design of the nasal stent and the position of the nasal stent in the nostril. (B) Unilateral NAM plate with nasal stent showing lip taping. (C) The bilateral NAM plate in position showing the tape adhered to the prolabium and stretched to the plate and attached to the plate.

Nonsurgical columella lengthening in bilateral cleft lip and palate

In bilateral cases, the attention is focused on nonsurgical lengthening of the columella by manipulation of the nasal stent. To achieve this objective, a horizontal band of denture material is added to join the left and right lower lobes of the nasal stent, spanning the base of the colume-lla (Fig 9.3A). This band sits at the nasolabial junction and defines this angle. Tape is adhered to the prolabium, and it applies a downward force to stretch the columella tissues. This tape contains elastics that are engaged to the retention buttons. The downward pull on the prolabium and columella provides a counter force to the upward force that is applied to the nasal tip by the stent. Taping downward on the prolabium helps to lengthen the columella and vertically lengthens the often small prolabium. The horizontal lip tape is added after prolabium tape is in place.

Benefits of NAM

There are several benefits of the NAM technique in the treatment of cleft lip and palate deformity. Proper alignment of the alveolus, lip and nose helps the surgeon to achieve a better and more predictable surgical result. Long-term studies of NAM therapy indicate that the change in nasal shape is stable.2 There is less scar tissue as the surgical correction is less invasive. The improved quality of primary surgical repair reduces the number of surgical revisions, oronasal fistulas and secondary nasal and labial deformities (Fig 9.4).

Figure 9.4 A bilateral complete cleft lip and palate infant treated with NAM therapy (A) Prenasoalveolar molding therapy (B) Postnasoalveolar molding therapy; note the nonsurgical columella elongation (C) Postsurgical photograph (D) 1-year follow-up.

If the alveolar segments are in the correct position and a gingivoperiosteoplasty is performed, the resulting bone bridge across the former cleft site improves the conditions for eruption of the permanent teeth and provides them with better periodontal support. Studies have also demonstrated that 60% of the patients who underwent NAM and gingivoperiosteoplasty did not require secondary bone grafting.3 The remaining 40% who did need bone grafts showed more bone remaining in the graft site compared with patients who have had no gingivoperiosteoplasty.4 Fewer surgeries also result in substantial cost savings for families, insurance companies and government medical programs. Studies have demonstrated that midfacial growth in the sagittal and vertical plane was not affected by gingivoperiosteoplasty.5

Since the introduction of NAM, there have been significant differences in the outcome of primary surgical cleft repair. With proper training and clinical skills, NAM has been demonstrated to provide tangible benefits to the patients, as well as to the surgeons performing the primary repair.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses