The Disease Control Phase of Treatment

After a thorough examination and diagnostic workup of the patient, both the new and the experienced practitioner may be tempted to finalize the treatment plan and move on with actual treatment. Certainly, there is merit in having a single, clear, well-sequenced restorative plan of care. A fundamental question to consider at this point, however, is whether the plan (exclusive of the systemic and acute phase elements discussed in Chapters 5 and 6) should be one continuous successive list, including all periodontal, restorative, orthodontic, endodontic, or surgical treatments required, or does the patient’s oral health require a separate disease control phase of treatment to establish a stable foundation for future reconstruction?

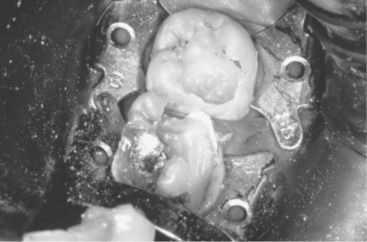

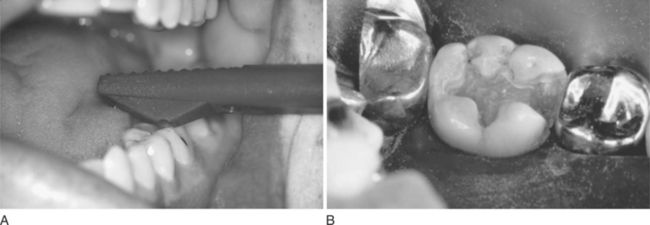

Figure 7-12 Cracked tooth syndrome. A, Placement of a Toothsleuth to test for a cracked tooth. B, Fracture line evident on the mesiofacial aspect of the floor of the preparation. (A, Courtesy Dr. D. Shugars, Chapel Hill, NC; B, courtesy Dr. A. Wilder, Chapel Hill, NC.)

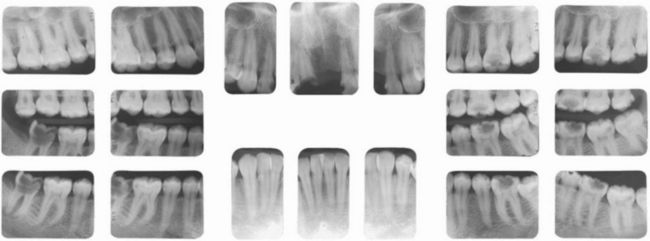

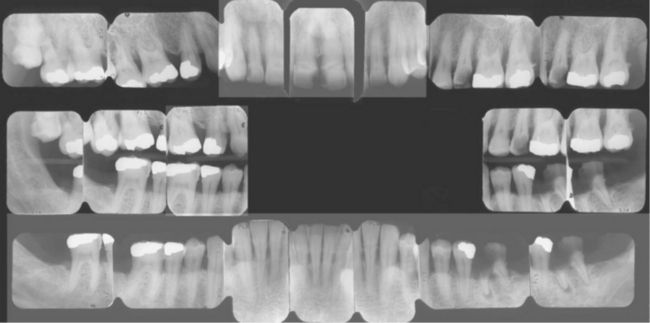

Figure 7-13 Large metallic restorations. Note that the deep bases on the maxillary second premolar and first molar appear to be in close proximity to the pulp. (Courtesy Dr. J. Ludlow, Chapel Hill, NC.)

PURPOSE OF THE DISEASE CONTROL PHASE

Disease control is appropriate when in the dentist’s judgment the questionable status of the patient’s oral health suggests the need for further stabilization before making final decisions on treatment, that is, treatment uncertainty. Disease control is also warranted when an intentional reevaluation of the patient is necessary to ensure control of oral disease and infection, that is, disease status uncertainty. Finally, in problematic situations that could be characterized as patient commitment uncertainty, a disease control phase allows the dentist to preserve, for a time, the maximum number of treatment options while testing the patient’s desires, resolve, commitment, compliance with oral hygiene recommendations, financial status, and comfort in the dental chair.

The purpose of the disease control phase is:

The disease control phase allows the practitioner to determine the cause or causes of disease, to assess risk factors, and to estimate the prognosis for control of disease and for the various treatment options. The disease control phase also provides both the practitioner and the patient with crucial information on which to base treatment recommendations and decisions. In general, when conditions warrant a disease control phase, nonacute and elective orthodontic, endodontic, periodontic, and oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures and any definitive reconstruction are postponed until its conclusion.

A disease control phase is not necessary in the patient whose oral disease is controlled or who does not demonstrate significant risk factors for new disease. It also is not needed for the patient whose oral disease will be eliminated de facto during definitive treatment. For example, consider the patient with severe periodontal attachment loss whose treatment plan includes 14 extractions and the design, fabrication, and placement of complete maxillary and mandibular overdentures. Because this treatment generally has a predictable outcome, with disease essentially eliminated by the definitive treatment itself, a disease control phase is usually unnecessary. On the other hand, the patient with seven variously sized carious lesions and multiple risk factors for new caries would be likely to benefit from a separate disease control phase of treatment. In this case, it would be inappropriate for the dentist to provide crown restorations before the caries process has been controlled and caries risk factors neutralized or eliminated.

Minimally, the disease control phase should include plans for management of the following:

The plan for the disease control phase includes a posttreatment assessment. Although the concept of posttreatment assessment is discussed in detail in Chapter 9, the unique aspects of assessment following a disease control phase merit discussion here because of importance and timing. Using quantifiable measures whenever possible, such an assessment provides an opportunity for the practitioner to confirm that disease and infection are under control. The patient with active caries for whom reduction in the concentration of cariogenic bacteria can be demonstrated represents one example. The patient with rapidly progressive periodontitis and a confirmed reduction in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans counts is another.

An assessment at the conclusion of the disease control phase allows both patient and dentist to make a realistic evaluation of feasible and practical treatment options. Previously considered options can be revisited, and the prognosis can be determined with more certainty. In addition, the patient can have a clearer understanding of the level of financial resources, time, and energy he or she will need to invest in the process. With a track record already established for the patient, the dentist can make treatment recommendations with a better sense of the expected outcomes.

At the time of the assessment, new options for definitive treatment may also become apparent. The patient who, at the outset, only aspired to reparative treatment may now be prepared to consider other possibilities. Having successfully completed the disease control phase, the patient may have a new appreciation of self and the improvements that dental treatment can provide. For example, when periodontal tissues are no longer tender and anterior teeth have been restored to an esthetically pleasing shape and color, the patient may be prepared to consider orthodontic tooth movement to correct anterior crowding. Before disease control therapy, the patient may not have considered and probably would not have wanted orthodontic therapy. Furthermore the dentist may have been appropriately reluctant to even suggest orthodontic treatment to the patient before a successful outcome to the disease control phase was assured.

STRUCTURING THE DISEASE CONTROL PHASE

When the dentist has determined the need for a disease control phase, the next step is to formulate and sequence that plan. Many of the principles that apply to the development of the overall plan of care also have application to disease control. During this phase, however, those principles may take on a unique importance. In addition, other principles are specific to disease control.

As the dentist begins to shape the plan for this phase, there must be consideration of all reasonable treatment options. In conversation with the patient, there will need to be a winnowing process that leads to a single mutually agreeable approach to the disease control plan. Once a general plan is agreed upon, the dentist helps the patient set achievable treatment goals and build realistic expectations for treatment outcomes. The dentist will need to establish clear, specific, and quantifiable standards for success (i.e., outcomes measures), such as setting a target plaque score and bleeding index. The dentist should specify, preferably in writing, the factors that will be evaluated at the posttreatment assessment that closes this phase of care. In addition, the dentist delineates the successive steps to be implemented both when the patient does and does not meet the standards for success. The dentist may also wish to share briefly with the patient various definitive phase options that may be relevant to consider upon completion of the disease control phase. This discussion should normally include options that may emerge (1) if the disease control therapy is successful, and (2) if disease control therapy is not successful. In this manner, the patient can be well prepared for either eventuality. Treatment during the disease control phase is sequenced by priority of patient need rather than by dental discipline. The accompanying In Clinical Practice box features the keys to a successful disease control phase of treatment.

General guidelines for sequencing elements of the treatment plan are discussed in Chapter 3. The following suggestions have particular relevance to the disease control phase.

Figure 7-1 Patient with numerous carious lesions of varying size. The asymptomatic and nonrestorable lower right second molar and the asymptomatic and necrotic lower left first molar are not urgent needs. The management of the patient’s esthetic problems, the initiation of a caries control protocol, and the restoration of the numerous moderately sized carious lesions should take precedence over the treatment of these two teeth. (Courtesy Dr. Chai-U-Dom, Chapel Hill, NC.)

Figure 7-2 Situation in which management of deep carious lesions should precede initial periodontal therapy. (Courtesy Dr. I Aukhil, Chapel Hill, NC.)

Specific circumstances and sound clinical judgment will of course create many exceptions to each of these general guidelines. Nevertheless the overarching priority should be saving key and salvageable, though questionable, teeth with the minimal necessary treatment for the simple reason that it would be inefficient and foolish to invest extensive time and resources in an attempt to save teeth that may eventually be lost. The sequencing of this minimalist approach is driven by many factors, including patient desires, symptoms, presence (or absence) of infection, and the other issues previously described in this section.

COMMON DISEASE CONTROL PROBLEMS

Dental Caries

The etiology, natural history, and the incidence and prevalence of dental caries are better understood today than they were 2 decades ago. Restorative materials and techniques continue to improve. New diagnostic methods are promising, but have not yet fully eliminated clinical controversies and confusion, as clinicians continue to disagree about how and when carious lesions should be treated. Although the public health benefits of fluoridated water have been well documented and fluoridation has effectively slowed the incidence of caries, the disease is far from eradicated. Although caries rates in the population at large have stabilized or declined, significant and growing segments of the U.S. population continue to develop high rates of decay and, despite the efforts of clinicians, researchers, and public health specialists, dental caries continues to afflict humankind.

A functional framework for the overall management of the patient with serious dental caries problems includes the following elements:

Undergirding this framework is the recognition that caries is an infectious disease and that the fundamental objective of any caries control program is to reduce the burden of pathogenic microbes and thereby limit, or preferably eliminate, the infectious process. Once the infection has been controlled, long-term monitoring is essential to ensure that the infection has not been returned.

Caries Control: A Working Definition

The term caries control is sometimes applied to individual restorations placed in teeth that have lesions of substantial size. It also is sometimes used to characterize the use of sealants or conservative composite restorations intended to prevent, control, and in some cases reverse new or incipient lesions. The term has been applied to dietary and/or behavioral approaches designed to prevent new caries, such as reducing refined carbohydrate and acid exposures between meals or increasing fluoride exposure. In this text, caries control means any and all efforts to prevent, arrest, remineralize, or restore carious lesions. A caries control protocol is a comprehensive organized plan designed to arrest or remineralize early carious lesions, to eradicate overt carious lesions, and to prevent the formation of new lesions in an individual who has a moderate or high rate of caries formation or is at significant risk for developing caries in the future.

Objectives, Strategies and Rationale for the Caries Control Protocol

The two primary objectives for the caries control protocol are:

Conventional dental restorative procedures and placement of pit and fissure sealants can be effective in eliminating active carious lesions which are also important localized sites harboring the pathogenic bacteria. Sealants placed and effectively retained on pits and fissures and white spot lesions will effectively entomb the entrapped organisms. Sealants also help reduce the number of susceptible sites in the mouth that may become inoculated with cariogenic bacteria in the future. Without reducing the pathogenic bacterial load, however, these efforts are often fruitless as the disease process can continue unabated. A caries vaccine would be the ideal strategy to reduce the microbial load of pathogenic bacteria to insignificant numbers, but unfortunately, no such vac-cine as yet exists. Progress is being made on this front, but significant obstacles remain. Another approach that is being pursued currently is replacement therapy, which involves replacing pathogenic (acid producing) Streptococcus mutans with innocuous and noncariogenic (base producing) strep species. This is consistent with a “probiotic” approach in which pathogens are eliminated from the dental biofilm, and only “good” plaque remains. The concept is reasonable, but has not yet come to fruition.

Antibiotic therapies have been considered and attempted, but have significant limitations. Although the use of systemic antibiotics can effectively reduce the number of Streptococcus mutans the primary causative agent in dental caries the risks far outweigh the possible benefits. At present, no antibiotic specific for Streptococcus mutans has been identified, and with overuse of currently available antibiotics there is significant risk for the patient to develop drug sensitivity, drug resistant organisms, suprainfection, or superinfection. Furthermore, after the course of an antibiotic has been discontinued, there is no assurance that the mouth will not become repopulated with an even more aggressive strain of Streptococcus mutans. Topical antibiotics have demonstrated some usefulness, but as yet do not have either the desired substantivity or specificity. One of the many virtues of fluoride is that it does have an antimicrobial effect, particularly in high concentrations. When used at therapeutic levels, it can help diminish, but will not eliminate, Streptococcus mutans colonization. Chlorhexidine (CHX) is known to be a potent antimicrobial, but the effects are not permanent and patients may be discouraged by the unpleasant taste and the extrinsic tooth staining. CHX mouth rinses are effective against Streptococcus mutans, and CHX does have the desired substantivity. When used as a daily 30-second rinse at bedtime, the residual taste is less of an issue, and a 14-day regimen will provide Streptococcus mutans suppression for 12 to 26 weeks. It has been demonstrated that suppression of Streptococcus mutans can be maintained following cessation of rinsing with CHX mouthwash via the continued daily use of xylitol gum.1 The simultaneous use of CHX and fluoride rinses or gels has shown promise, but the efficacy of this regimen has not as yet been demonstrated.2 Povidone-iodine, a broad spectrum antibiotic, has been used effectively in infants with early childhood caries. It has been speculated, though not yet conclusively demonstrated, that this substance may have some usefulness in older adults who have dexterity problems and who are at high risk for root caries.

Given the limitations of currently available antimicrobial therapies, the following more traditional strategies continue to be important elements of the caries control protocol.

Basic Caries Control Protocol

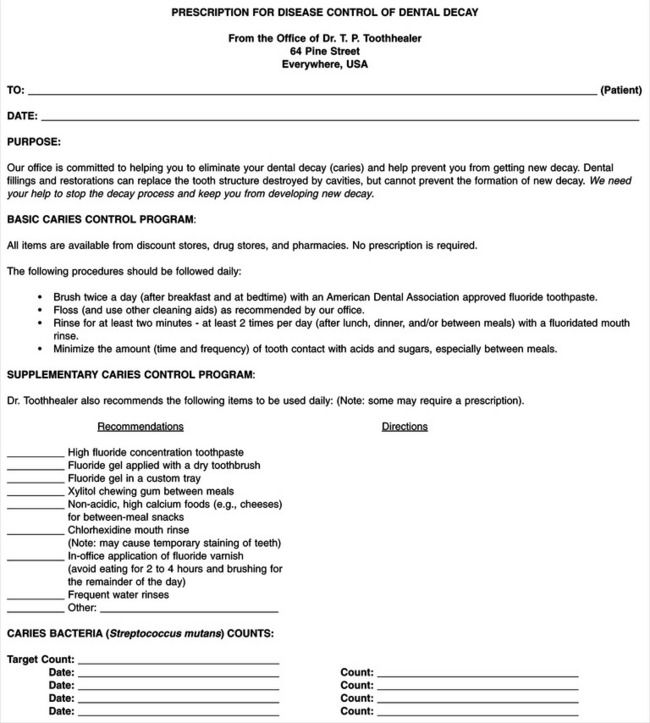

The basic caries control protocol should be implemented for all patients who have more than three active lesions at the initial oral examination, or more than two new lesions at a periodic recall examination (Table 7-1). Designed for simplicity and effectiveness, most of the products used in the protocol are readily available over-the-counter and involve techniques that are no more difficult to master than routine oral self-care procedures. The dentist and staff require minimal chair time to explain the protocol and its use to the patient. A sample office handout for this purpose is shown in Figure 7-3.

Table 7-1

| Item | Rationale |

| Caries activity tests (CATs) | (See In Clinical Practice: Caries Activity Tests) |

| Oral prophylaxis (professional) | Removes plaque and plaque retentive accretions; makes tooth surfaces more receptive to fluoride uptake |

| Oral self-care instructions* | Removes plaque and reduces the potential for developing smooth surface caries |

| Professional fluoride gel or varnish† application at each scaling or preventive (recall/maintenance) visit | Remineralization of hydroxyapatite with fluorapatite; antimictobial effect; short-term contribution to fluoride reservoir; reduced caries incidence; most effective when given at more frequent time intervals (less than 6 mo) |

| Reduce frequency and duration of acid and sucrose (refined carbohydrate) exposure | Eliminates substrate for cariogenic bacteria; reduces acid-induced dissolution of tooth structure |

| Over-the-counter fluoride dentifrice and fluoride rinses (use daily) | Antimicrobial effect; remineralizes tooth structure, replenishes intraoral fluoride reservoir, increases caries resistance |

| Restore carious lesions with direct-fill provisional or definitive restorations‡ (Note: definitive cast restorations are not recommended) | Eliminates nidus of infection; improves cleansability; arrests caries progression |

| Sealants on susceptible pits and fissures (e.g., exposed pits and fissures in adolescents or in adults when other pits and fissures have needed restoration) | Eliminates sites of infection and potential for inoculation of other sites; prevention of pit and fissure caries |

*Flossing has not been shown to reduce caries incidence. It is logical for the dental team to encourage its use because of its many other proven benefits, including the reduction of plaque formation and gingivitis. Some patients continue to have carious lesions develop even in the absence of high plaque scores. For these patients, it is particularly important to consider specific forms of antimicrobial therapy as part of the caries control regimen.

†In general, professionally applied fluoride varnish applications have been shown to be more effective than professionally applied fluoride gel treatments (Bader et al: Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 29(6):399-411, 2001, and Peterson et al: Acta Odontol Scand 62(3):170-176, 2004.

‡The merits of glass ionomer restorations as a means of inhibiting secondary caries are reviewed in What’s the Evidence?: Do Glass-Ionomer Restorations Prevent Recurrent Caries?

Optional Caries Interventions

Likely candidates for additional intervention include patients with unusually active or rampant caries, or those who have specific identifiable factors suggesting high risk for caries development. Suggestions or guidelines for possible interventions and their indications are listed in Table 7-2.

Table 7-2

| Problem | Suggested Intervention |

| Decreased quantity or quality of saliva | Oral hydration, salivary substitutes |

| Medication-induced xerostomia | Substitute for xerostomic medications (usually requires consultation with patient’s physician) |

| Continued incidence of new caries activity in spite of previous intervention | Custom fluoride trays for daily home use |

| Patient at risk for additional root or smooth surface caries | Fluoride varnish application |

| Patient who would benefit from higher level fluoride exposure, but is unwilling or unable to accept custom trays | Prescription dentifrice with high concentration fluoride |

| Any patient at risk for new caries who likes to chew gum | Ad lib use of xylitol chewing gum (good alternative for persons who crave betweenmeal high-sucrose snacks or drinks) |

| Patients with concurrent marginal periodontal disease and/or patients with Streptococcus mutans counts that remain high despite previous intervention | Chlorhexidine mouth rinses |

Patient Selection

Many patients with rampant caries suffer from pain, infection, difficulty chewing, loss of function, an unappealing smile, and a poor self-image. Their oral problems are often accompanied by and associated with complex general health and psychosocial problems. In such cases, the likelihood for successful long-term eradication of the disease, even with the best efforts of the patient and the dental team, may be poor. (See Chapter 17 for more in-depth discussion of these issues.) In some cases, if the patient is fully aware of these limitations at the outset of treatment (as should be the case), he or she may decide not to embark on an aggressive caries control protocol. Similarly the dentist, knowing full well that the chances of success are limited and that some factors are not controllable, may decide that the task is not worth the effort. In some instances, the evaluation process may lead the practitioner to suggest more rather than fewer extractions, thereby simplifying the plan and reducing both the cost and the time required. (This approach has sometimes been labeled robust treatment planning.)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses