7

Implant Site Preparation

Case 1: Sinus Grafting: Lateral

Guillaume Campard, DDS, MMSc, and Emilio I. Arguello, DDS, MSc

Case 2: Sinus Grafting: Crestal

Samuel Soonho Lee, DDS, and Nadeem Karimbux, DMD, MMSc

Case 3: Socket Grafting

Satheesh Elangovan, BDS, DSc, DMSc

Case 4: Ridge Split and Osteotome Ridge Expansion Techniques

Emilio I. Arguello, DDS, MSc, and Daniel Kuan-te Ho, DMD, MSc

Case 1

Sinus Grafting: Lateral

CASE STORY

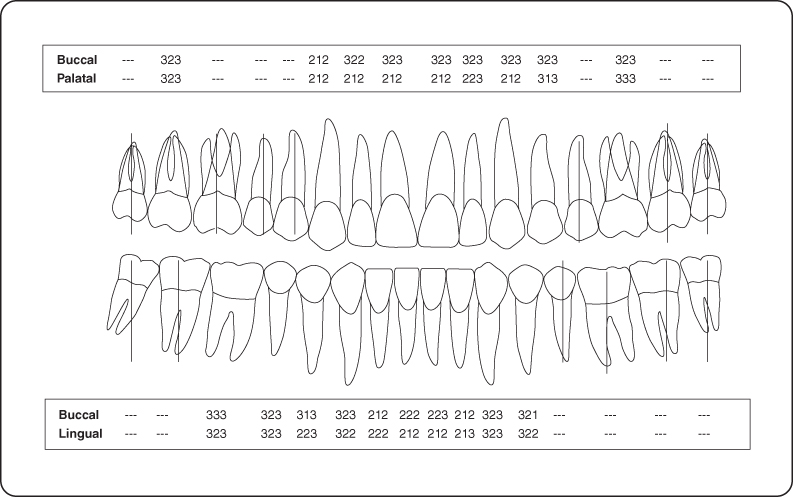

The patient was a 52-year-old male who presented to the Department of Periodontology for a consultation regarding the edentulous space in the maxillary right quadrant. His chief complaint was to have fixed restorations to replace the missing teeth. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the initial clinical examination.

Figure 1: Facial view of the maxilla and the mandible.

Figure 2: Occlusal view of the maxilla.

LEARNING GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

- To identify the indications for a sinus elevation

- To understand the preoperative considerations

- To be introduced to a surgical technique and biomaterial used to perform a sinus elevation

Medical History

The patient was in good health and had regular physical examinations. He did not report any allergies or sinus-related pathology.

Review of Systems

- Vital signs

- Blood pressure: 120/65 mm Hg

- Pulse rate: 65 beats/minute (regular)

Social History

The patient did not drink alcohol and did not consume recreational drugs. He had been smoking 10 cigarettes per day for the last 25 years.

Extraoral Examination

No significant findings were noted. The patient had no masses or swelling, no trismus. No palpable lymphadenopathy and the temporomandibular joints were within normal limits (Figure 3).

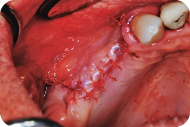

Figure 3: Probing pocket depth measurements.

Intraoral Examination

- The soft tissues of the mouth including tongue appeared normal. The oral cancer screen was negative.

- The gingival examination revealed a generalized mild marginal erythema and a melanotic macule in the gingiva (site #5) consistent with an amalgam tattoo (Figure 2).

- A hard tissue examination was completed by the referring general dentist.

- The edentulous ridge in the maxillary right quadrant had deformities in the buccolingual and apico-coronal directions (Seibert class 3) (Figure 1).

Occlusion

Lack of posterior support, unprotected occlusion, cross-bite occlusion #22 and 27.

Radiographic Examination

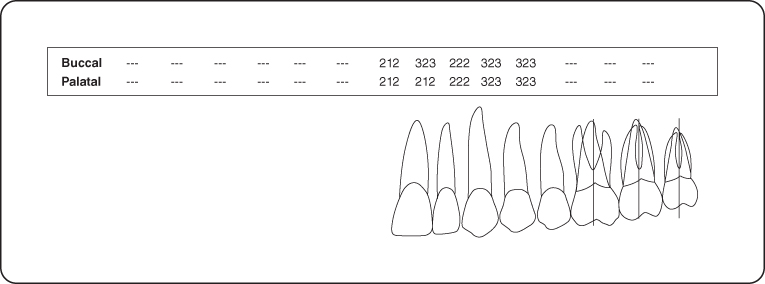

A periapical radiograph of the right posterior maxillary sextant showed that the maxillary right sinus was pneumatized and the height of bone mesial to tooth #2 was about 1 mm (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Radiographic evaluation: the periapical radiograph of the maxillary right quadrant shows the pneumatized sinus and the lack of bone.

Treatment Plan

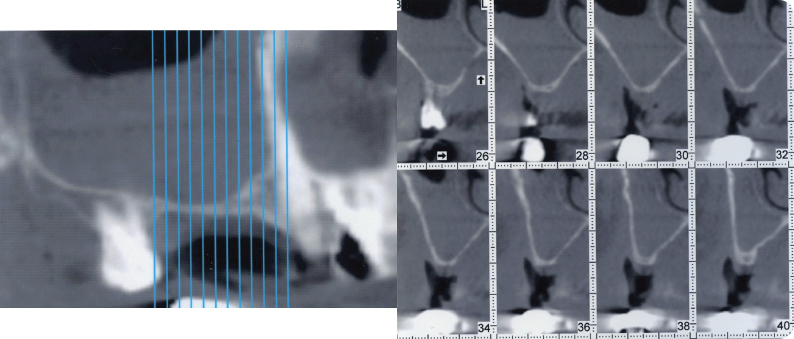

Prosthodontic, endodontic, and orthodontic consultations are required to establish a comprehensive treatment plan. A cone beam computed tomography (CT) scan is ordered for the maxillary arch to get further information on the anatomy and the condition of the sinus (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Cone beam CT scan of the maxillary right sinus. The Schneiderian membrane appears thickened. The residual bone height is 1 mm in sites #3 and 4.

A thickening of the Schneiderian membrane is observed in the maxillary right sinus (Figure 5). A consultation with an otolaryngologist is indicated to rule out any sinus pathology. He performed a nasal endoscopy and reported a “very mild edema and erythema.” He diagnosed a mild sinusitis and did not consider any contraindication for the sinus elevation procedure.

The final treatment plan included a full-mouth prosthetic and occlusal rehabilitation, including an implant supported fixed partial denture #3-x-5.

Treatment

The patient received oral hygiene instructions and a prophylaxis. Tooth #2 was extracted prior to the sinus elevation.

Preoperative Consultation

The medical history was reviewed. The consent form addressing benefits and risks associated with the procedure was reviewed with the patient. Accessibility to the surgical site was clinically assessed. The CT scan showed that less than 4 mm of bone was present in the edentulous ridge area so a lateral window approach was selected to achieve 10–12 mm of bone augmentation in sites #3, 4, and 5. No evidence of the lateral branch of the posterior superior lateral artery could be seen on the CT scan (Figure 5). The following prescriptions were delivered to the patient: amoxicillin 500 mg (tid for 10 days starting 24 hours before the procedure), ibuprofen 600 mg (every 4–6 hours as needed for pain), and Peridex 0.12% (bid).

Sinus Elevation Procedure

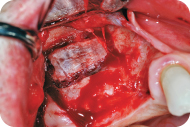

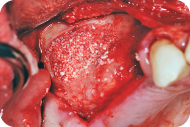

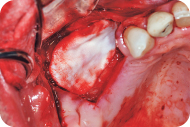

A procedural sedation and analgesia nerve block and local infiltrations were achieved with lidocaine 2% (epinephrine 1/100,000) (Figure 6). A full-thickness flap was elevated in the maxilla right quadrant to expose the cortical bone of the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus. A lateral window (20 mm × 8 mm) was outlined with a piezotome until the Schneiderian was visible (Figure 7). The Schneiderian membrane was elevated in a medial and anterior direction so that a space could be created in between the Schneiderian membrane and the bony floor of the sinus. A collagenic membrane was placed in the sinus against the membrane (Figure 8). Bone grafting material (a mix of rehydrated freeze-dreid bone allograft [FDBA] and anorganic bovine bone mineral) was placed into the space created into the sinus (Figure 9). A collagenic membrane was placed over the lateral window (Figure 10) and the flap was repositioned and sutured in its initial position (Figure 11). A panoramic radiograph was taken at the end of the surgery. The bone grafting material appears well contained in the maxillary right sinus (Figure 12).

Figure 6: Preoperative condition, buccal view.

Figure 7: The lateral window is outlined with a piezotome.

Figure 8: The Schneiderian membrane is elevated. A collagenic membrane is inserted against the membrane.

Figure 9: The bone grafting material is placed into the sinus in between the Schneiderian membrane and the floor of the sinus.

Figure 10: A collagenic membrane is placed over the lateral window.

Figure 11: The flap is repositioned and sutured to achieve primary closure.

Figure 12: Panoramic radiograph the day of the procedure.

Discussion

Although a high predictability of sinus elevation procedures have been extensively reported in the literature as it relates to the regeneration of bone in a pneumatized maxillary sinus, this particular case presents some challenges that could compromise some determinants of success. One of the risk factors identified and discussed in the medical history is the smoking status of the patient, which exposes him to a more elevated risk of complications. Thus an interdisciplinary approach was necessary where a well-coordinated team including the otolaryngologist and restorative dentist worked simultaneously in their respective fields in conjunction with the periodontist to provide the maximum benefit of the therapy for the patient and to evaluate and limit the risks of complications.

The surgical procedure went as planned and the patient complied with all the postoperative instructions given. The patient was seen for postoperative visits at 1 week to remove the sutures and at 3 and 6 weeks to monitor his healing response. The allocated time for healing prior to implant placement was 6 months, which corresponds to the remodeling and maturation of newly formed bone and concurs with what is suggested in the literature. Panoramic and periapical radiographs were taken to have a preliminary assessment of the amount of newly formed bone present. However, a new CT scan if performed could have provided more information regarding the volume, the anatomy, and the irregularities of the newly formed bone. It was determined, however, that the regenerated site could allow the placement of two implant fixtures, which were placed in sites 3 and 5 and will support a three-unit fixed prosthesis (FPD 3-X-5).

Self-Study Questions

A. What is the rationale for performing a sinus elevation?

B. What are the anatomic landmarks to know to perform a sinus elevation?

C. What are the techniques used?

D. Which biomaterials can be used in a sinus elevation? Is there histologic evidence of bone formation?

E. What are the determinants of success in a sinus elevation?

F. Are implants placed in a sinus elevated site as successful as implants placed in pristine bone? Does the surgical technique have an influence on the implant survival rate in the long term?

G. What are the complications associated with sinus elevations? How do you manage these complications?

Answers located at the end of the chapter.

References

1. Mosby’s Dental Dictionary. 2nd ed. Elsevier, 2008.

2. Boyne JP, James RA. Grafting the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous marrow and bone. J Oral Surg 1980;38:613–616.

3. Wood RM, Moore DL. Grafting of the maxillary sinus with intraorally harvested autogenous bone prior to implant placement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1988;3:209–214.

4. Tatum H Jr. Maxillary and implant reconstructions. Dent Clin North Am 1986;30:207–229.

5. Testori T, Del Fabbro M, et al. Maxillary Sinus Surgery and Alternatives in Treatment. Chicago, IL: Quintessence, 2006.

6. Ella B, Sédarat C, et al. Vascular connections of the lateral wall of the sinus: surgical effect in sinus augmentation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2008;23:1047–1052.

7. Uschida Y, Goto M, et al. A cadaveric study of maxillary sinus size as an aid in bone grafting of the maxillary sinus floor. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998;56:1158–1163.

8. Ella B, Noble Rda C, et al. Septa within the sinus: effect on elevation of the sinus floor. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;46:464–467.

9. Kim MJ, Jung UW, et al. Maxillary sinus septa: prevalence, height, location and morphology. A reformatted CT scan analysis. J Periodontol 2006;77:903–908.

10. Summers RB. Sinus floor elevation. J Esthet Dent 1998;10:164–171.

11. Jensen OT, Shulman LB, et al. Report of the sinus consensus conference of 1996. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1998;13(Suppl):11–32.

12. Del Fabbro M, Testori T, et al. Systematic review of survival rates for implants placed in the grafted maxillary sinus. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2004;24:565–577.

13. Wallace SS, Froum SJ, et al. Tarnow DPSinus augmentation utilizing anorganic bovine bone (Bio-Oss) with absorbable and nonabsorbable membranes placed over the lateral window: histomorphometric and clinical analyses. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2005;25:551–559.

14. Kahnberg KE, Vannas-Löfqvist L. Sinus lift procedure using a 2-stage surgical technique: I. Clinical and radiographic report up to 5 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2008;23:876–884.

15. Wallace SS, Froum SJ. Effect of maxillary sinus augmentation on the survival of endosseous dental implants. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol 2003;8:328–343.

16. Pjetursson BE, Tan WC, et al. A systematic review of the success of sinus floor elevation and survival of implants inserted in combination with sinus floor elevation. Part I: lateral approach. J Clin Periodontol 2008;35:216–240.

17. Boyne PJ, Lilly LC, et al. De novo bone induction by recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) in maxillary sinus floor augmentation. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 2005;63:1693–1707.

18. Boyne PJ, Marx RE, et al. A feasibility study evaluating rhBMP-2/absorbable collagen sponge for maxillary sinus floor augmentation. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1997;17:11–25.

19. Valentini P, Abensur D, et al. Histological evaluation of Bio-Oss in a 2-stage sinus floor elevation and implantation procedure. A human case report [review]. Clin Oral Implants Res 1998;9:59–64.

20. Coatoam GW, Krieger JT. A four-year study examining the results of indirect sinus augmentation procedures. J Oral Implantol 1997;23:117–127.

21. Kim DM, Nevins ML, et al. The efficacy of demineralized bone matrix and cancellous bone chips for maxillary sinus augmentation. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2009;29:415–423.

22. Tarnow DP, Wallace SS, et al. Histologic and clinical comparison of bilateral sinus floor elevation with and without membrane barrier placement in 12 patients. Part 3 of an ongoing prospective study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2000;20:116–125.

23. Torella F, Pitarch J, Cabanes G, et al. Ultrasonic ostectomy for the surgical approach of the maxillary sinus: a technical note. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1998;13:697.

24. Papa F, Cortese A, et al. Outcome of 50 consecutive sinus lift operations. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 2005;43:309–313.

25. Valentini P, Abensur DJ. Maxillary sinus grafting with anorganic bovine bone: a clinical report of long-term results. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Implants 2003;18:556–560.

26. Fugazzotto PA, Vlassis J. Report of 1633 implants in 814 augmented sinus areas in function for up to 180 months. Implant Dent 2007;16:369–378.

27. Ferrigno N, Laureti M, et al. Dental implants placement in conjunction with osteotome sinus floor elevation: a 12-year life-table analysis from a prospective study on 588 ITI implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 2006;17:194–205.

28. Chen L, Cha J. An 8-year retrospective study: 1,100 patients receiving 1,557 implants using the minimally invasive hydraulic sinus condensing technique. J Periodontol 2005;76:482–491.

29. Rosen PS, Summers R, et al. The bone-added osteotome sinus floor elevation technique: multicenter retrospective report of consecutively treated patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1999;14:853–858.

30. Tan WC, Lang NP, et al. A systematic review of the success of sinus floor elevation and survival of implants inserted in combination with sinus floor elevation. Part II: transalveolar technique [review]. J Clin Periodontol 2008;35(8 Suppl):241–254.

31. Tonetti MS, Hammerle CHF. Advances in bone augmentation to enable dental implant placement: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol 2008;35(Suppl 8):168–172.

32. Krennmair G, Krainhofner M, et al. Maxillary sinus lift for single implant-supported restorations: a clinical study. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Implants 2007;22:351–358.

33. Khoury F. Augmentation of the sinus floor with mandibular bone block and simultaneous implantation: a 6-year clinical investigation. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Implants 1999;14:557–564.

34. Schwartz-Arad D, Herzberg R, et al. The prevalence of surgical complications of the sinus graft procedure and their impact on implant survival. J Periodontol 2004;75:511–516.

35. Zijderveld SA, van den Bergh JP, et al. Anatomical and surgical findings and complications in 100 consecutive maxillary sinus floor elevation procedures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66:1426–1438.

36. Fugazzotto PA, Vlassis J. A simplified classification and repair system for sinus membrane perforations. J Periodontol 2003;74:1534–1541.

37. Elian N, Wallace S, et al. Distribution of the maxillary artery as it relates to sinus floor augmentation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2005;20:784–787.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

A. The absence of teeth in the posterior maxilla can become a restorative challenge when little or no alveolar bone is present. The presence of the maxillary sinus as the basis of the maxillary alveolar process can be an obstacle to the placement of an implant. In addition, sinus pneumatization, described as an enlargement of the maxillary sinus due to the aging process and as a result of the loss of maxillary teeth [1], tends to reduce the amount of bone available over time. As a consequence, there is usually a need to increase the bone volume in the posterior maxilla prior to implant placement. The goal of a sinus elevation procedure is to surgically increase the alveolar bone height by grafting bone in the floor of the maxillary sinus [2]. Evidence has shown that the imposition of an appropriate grafting material placed along the antral floor and below the Schneiderian membrane can successfully lead to viable antral bone formation and remodeling [2–4]. After a healing period of time needed for bone formation and maturation, an implant can be placed with adequate primary stability, osseointegrate, and eventually be restored with high rates of success [5].

B. The maxillary sinus is an air-filled space located in the body of the maxilla. It is a pyramid with a nasal wall (its base), an anterior wall, a superior wall (the orbital floor), a lateral wall, and an inferior wall (the maxillary alveolar process). It is innervated by branches of V2 and is supplied by branches of the internal maxillary artery: the infraorbital artery, the posterior lateral artery, and the posterior superior alveolar artery that have inconsistent branches running along the lateral wall of the sinus [6]. Evaluation for the presence of these branches in CT scans is necessary prior to surgery to prevent perioperative hemorrhage if a lateral window approach is selected. The presence of these branches needs to be evaluated prior to surgery to prevent preoperative hemorrhage if a lateral window approach is selected. The sinus drains in the nasal cavity through an ostium located at the superior aspect of its medial wall (nasal wall), about 28.5 mm above the sinus floor [7]. A sinus elevation should never obliterate the ostium as to not compromise the sinus drainage. Sinus septa are commonly present in the apical third of the sinus. They represent a challenge during sinus elevations. Ella et al [8] report that 40% of patients have bony septa that can partly or totally compartmentalize the sinus. Septa would be more present in the middle region of the sinus (50%) and would be highest on the medial area [9]. The radiographic examination with a CT scan will help identify them and better evaluate the anatomic challenges faced during the procedure.

C. There are two main approaches to performing a sinus elevation:

1. The crestal approach: This technique gives access to the sinus floor through the ridge crest. Tatum [4] first described a technique involving the following sequence: flap elevation, removal of the bone until the cortical bone of the sinus floor is exposed, greenstick fracture of the cortical bone with osteotomes and burs, elevation of the Schneiderian membrane, and placement of the bone grafting material. Summers [10] described a variation of Tatum’s technique called the “osteotome sinus floor elevation technique.” Osteotomes of increasing diameters with concave tips are used to relocate the existing alveolar bone apically and laterally toward the antral floor. Some bone grafting material can be added to the procedure (“bone-added osteotome sinus floor elevation technique”) to decrease the risk of membrane perforation and better control the ultimate height of the grafted space.

2. The lateral window approach: This technique gives access through the lateral wall of the sinus [3,4]. A full-thickness flap is elevated to expose the lateral antral wall, a window is made in the bony wall using rotary or hand instruments, and then it is displaced medially. The membrane is carefully elevated, and the bone is placed in the space located below the Schneiderian membrane and above the sinus floor.

D. Autografts (extraoral and intraoral), allografts (FDBA, decalcified freeze-dried bone allograft [DFDBA]), xenografts (anorganic bovine bone mineral), and alloplasts (calcium phosphate) have been used for bone grafting materials for more than 20 years. The sinus consensus conference of 1996 [11] approved autogenous bone as an acceptable grafting material. Other studies proved that bone substitutes including allografts and xenografts could be successfully used for sinus elevation [12,13]. Further evidence [14] has shown that autogenous bone is a viable option, although a higher rate of complications (including infections, bone resorption) was observed when compared with xenografts and allografts. Recent systematic reviews have shown that sinus elevation using bone substitutes alone or in combination with autogenous bone had a similar or even a better implant survival rate when compared with studies using autogenous bone only [15,16]. New materials such as bone morphogenic proteins (BMP-2) used with a collagenic sponge carrier have proved their efficacy and got Food and Drug Administration approval for sinus elevation procedures [17,18].

A few studies have provided histologic evidence of bone formation in a grafted sinus. Histology of an explant from the maxillary sinus showed new bone formation around the implant and the xenograft particulates [19]. Another study showed evidence of bone formation when autogenous bone alone or a mix of DFDBA and autogenous bone were initially used [20].

Boyne et al [17] and Kim et al [21] showed evidence of normal bone formation in an elevated sinus, respectively, when rhBMP-2 (Infuse) and demineralized bone matrix and cancellous bone chips (DynaBlast) were used as grafting material.

The placement of a membrane over the window is usually recommended to enhance the bone formation [22]. Both resorbable (collagenic) and nonresorbable (expandable polytetrafluoroethylene [ePTFE]) membranes can be used, although the resorbable one is more commonly used to avoid a surgical reentry.

E. The success of a sinus elevation procedure depends on a series of parameters that include chronologically an uneventful surgical procedure, minimal or no postoperative pain and complications, bone formation, osseointegration of implants, and their survival under functional load.

Some determinants promoting success have been reported in the literature. They include the following:

1. Absence of medical conditions (including systemic diseases, bisphosphonate, and irradiation), sinus pathology, and smoking. The patient should be referred to a physician if there is any significant medical condition reported during the preoperative examination.

2. The use of rough surfaced implants as opposed to machined surface implants to enhance the survival rate [15,16].

3. The use of particulates grafts or BMP-2 as opposed to block graft to decrease complications. However, autogenous block grafts remain a viable option [15,16].

4. The use of a membrane when a lateral window approach is selected [15,16].

5. The use of piezo surgical instruments to decrease the rate of complications at the time of osteotomy [23].

The surgeon should deliver regular postoperative instructions emphasizing these points:

1. Do not blow your nose

2. Do not sneeze

3. Do not travel by plane or scuba dive for the next 15 days

4. Do not engage in physical activity for a few days (i.e., strenuous exercise)

F. Implants placed in a sinus elevated site have a very high rate of success (>90%), which is comparable with implants placed in pristine bone [15]. Multiple studies have proved that the lateral approach is a predictable technique and allows implants survival rates of ≥95% over the long term [24–26]. Similar results can be found when a crestal approach is used [27,28]. Nevertheless, the amount of residual bone seems to have a significant impact on the implant survival rate with this technique; a minimum of 5 mm would be necessary to achieve a high success rate [29].

Evidence has shown that there are no statistically differences in implants survival rates when a lateral approach is used as opposed to a crestal approach. A recent meta-analysis reporting on 12,020 implants placed in sinus elevated sites with a lateral approach indicated an implant survival rate at 3 years of 90.1% [16], whereas the survival rate over the same period of time was 92.8% when a crestal approach was used [30]. If both surgical techniques are compatible with success, the Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology [31] stated that the question regarding the choice of the most appropriate procedure still needed to be addressed.

G. Complications associated with sinus elevation procedure can be divided into two categories:

1. The operative complications:

a. The perforation of the Schneiderian membrane is reported to be the most common complication and happens on average in 19.5% [16] and up to 58% [32] of the procedures. There is some controversy with regard to its impact on the implant survival [33,34].

b. Hemorrhage at the time of the osteotomy with the lateral approach, which is the consequence of the section of a branch of the posterior lateral artery running along the lateral wall of the sinus. Zijderveld et al [35] reported it happening in 2% of the cases.

c. Inadvertent implant migration in the sinus cavity and injury of the infraorbital neurovascular bundle have been rarely reported.

2. The postoperative complications:

a. Infection as a direct consequence of the procedure or as a result of an overfill of the sinus resulting in the absence of its drainage in the nasal cavity. Infections occur 2.9% of the time and would be correlated to membrane perforations [16].

b. Absence of adequate bone volume. It would be more common with autogenous bone [14].

c. Hematoma and wound dehiscence have also been reported.

3. Management of perioperative complications:

a. Perforation of the Schneiderian membrane: a resorbable membrane can be placed against the Schneiderian membrane and over the perforated area. If the perforation is small, Fugazzotto advocates not to try to repair it as long as it “folds over itself” [36]. If the perforation is large and cannot be repaired, the sinus elevation should be postponed after complete healing of the Schneiderian membrane.

b. Hemorrhage [37]: Pressure can be applied on the bleeding point with gauze until hemostasis is observed. If the severed vessel is located in a bony crypt, bone wax can be placed in it to act as a plug that encourages clot formation. One can also inject some local anesthetic with epinephrine 1/50,000 to enhance vasoconstriction. Vessel ligature and electrocautery have also been reported, although they need to be used with caution.

c. Inadvertent implant migration: The implant should be retrieved as soon as possible. An emergency consultation with an ORL should be scheduled.

4. Management of postoperative complications:

a. Infections: The first choice of therapy is the use of antibiotics and choosing the appropriate one for the specificity of the sinus infection. In that regard, Augmentin could be considered as the first choice followed by DNA gyrase inhibitors such as ofloxacin, levofloxacin, and so on. In addition, one could consider the use of broader spectrum antibiotics such as amoxicillin or clindamycin for penicillin-allergic patients. If the infection cannot be controlled with antibiotics, the removal of the bone graft might be necessary.

b. Inadequate bone volume: The clinical situation should be reevaluated. The options of placing shorter implants or performing a complementary sinus elevation can be discussed.

Case 2

Sinus Grafting: Crestal

CASE STORY

A 32-year-old Korean female who had had extensive restorative treatment by her general dentist came in for an implant consultation. However, many of her restorations had recurrent decay, and several restorations had failed continually. Her main goal for visiting the clinic was to have fixed implant restorations to replace missing teeth #14 and 15. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the initial clinical examination.

Figure 1: Facial view of the maxilla and the mandible.

Figure 2: Occlusal view of the maxilla.

LEARNING GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

- To understand the indications/contraindications for the crestal approach and what diagnostic information is needed to make this decision

- To understand the advantages and disadvantages of the crestal approach, including the sequence of treatment (internal sinus lift/graft/implant all at same time vs. internal sinus lift/wait for healing and then implant)

- To learn how to achieve good initial stability in situations with weak and a low amount of bone

- To understand the advantages/disadvantages of the Crestal Window Technique, Summer’s osteotome, balloon technique, hydraulic sinus condensing, use of bone condensing drills, and use of piezo tips

Medical History

The patient was in good health and had had regular physical examinations (she was a nurse in the Emergency Department). She did not report any allergies or sinus-related pathology.

Review of Systems

- Vital signs

- Blood pressure: 135/85 mm Hg

- Pulse rate: 65 beats/minute (regular)

Social History

The patient did drink alcohol, and she smoked 10 cigarettes per day. This habit had been shown to impact the survival rates of endosseous dental implants, according to research. Therefore, the patient was asked to stop smoking at least for 1 month before dental implant surgery.

Extraoral Examination

No significant findings were noted. The patient had no masses or swelling, and no trismus. No palpable lymphadenopathy was observed, and the temporomandibular joints were within normal limits (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Probing pocket depth measurements of the maxillary left quadrant.

Intraoral Examination

- The soft tissues of the mouth including the tongue appeared normal. The oral cancer screening was negative.

- The gingival examination revealed a generalized mild marginal erythema.

- A hard tissue examination was completed by the referring general dentist.

- The edentulous ridge in the maxillary left quadrant had slight deformities in the buccolingual and apico-coronal directions (Seibert class 3) (Figure 1).

Occlusion

Lack of posterior support, unprotected occlusion, group function was noted.

Radiographic Examination

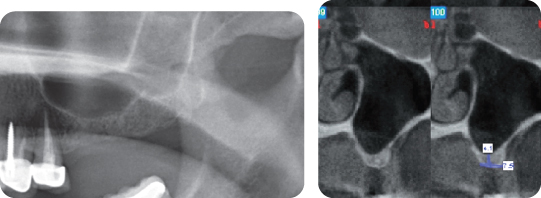

A digital panoramic radiograph showed a pneumatized left maxillary sinus. Cross-sectional computed tomography (CT) showed about 4.1 mm of initial bone height with a buccal lingual dimension of 7.5 mm. There was slight septum on distal of #15 area, and #14, 15 area was a concave shape, making transalveolar technique favorable (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Cone beam CT scan of the maxillary right sinus. The Schneiderian membrane appears healthy and thin. The residual bone height is 4.1 mm in sites #14 and 15. The septum present on the distal of #15 area with a concave shape in #14, 15 area makes transalveolar technique favorable.

Good patency of the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus was observed on cross section of the CT scan. This is important because it allows drainage of mucus and foreign material out of the maxillary sinus [1]. If this opening is obliterated, sinusitis will develop with the patient having symptoms of “pressure in the sinus.” CT shows that sinus membrane is not thickened, which indicates a healthy sinus. The cavity of maxillary sinus is clear and free of sinus pathogenesis.

Treatment

Although a comprehensive treatment plan was presented to the patient to address all of the issues, the patient only sought #14, 15 fixed implant prosthesis for now. All active disease was treated.

The patient received oral hygiene instructions and a prophylaxis. She was premedicated with amoxicillin 500 mg tid, metronidazole 500 mg tid, and Sudafed 30 mg [1].

Preoperative Consultation

The medical history was reviewed. The consent form addressing benefits and risks associated with the procedure was reviewed with the patient. The patient emphasized that she could not afford to miss work and the procedure must be atraumatic. Therefore, we offered a crestal approach to reduce morbidity.

Sinus Elevation Procedure

A posterior superior alveolar nerve block, greater palatine nerve block, and local infiltrations were achieved with two carpules of Septocaine 4% with epinephrine 1 : 100,000) (Figure 5). A full-thickness palatal flap was elevated in the maxillary left quadrant to expose the crestal ridge of #14, 15 site. The palatal flap was used for three reasons: unilateral retraction of flap, less postoperative pain (all incisions in keratinized tissue, and prevention of oral antral communication (due to window present on crestal). In this case a novel Crestal Window Technique using specific drill bits was used. The osteotomy site was marked with “pointed trephine” (Figure 6). The use of a regular trephine is very technique sensitive because trephine has a tendency to glide out of the intended site. The pointed trephine engages the center point first, thus preventing sliding of the trephine bur from the intended site (Figure />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses