Chapter 7

Behaviour change

Plaque control and smoking cessation

Introduction

This chapter discusses two of the most important interventions in periodontal treatment—oral hygiene instruction and smoking cessation. These interventions may also represent some of the most challenging aspects of periodontal treatment because they are dependent on achieving permanent changes in behaviour by the patient. The chapter adopts a “how to do it” presentation style rather than the illustrative individual case reports used throughout much of the rest of the book. We have done this because there are many individual factors to consider for different patients, and thus we consider that the material is more suited to the style adopted here.

Plaque control

The importance of achieving a satisfactory level of plaque control for successful periodontal treatment outcomes has been emphasized throughout this book. What constitutes a “satisfactory” level of plaque control is potentially a more thorny issue. In general, a reasonable target level of plaque control is considered to be an approximately 20% plaque score that is demonstrated over a number of visits. However, because disease susceptibility varies enormously among individuals, this level needs to be considered for each individual patient according to his or her susceptibility, such that in a highly susceptible patient the aim should be to achieve a plaque score that is as low as possible, whereas pragmatically a higher plaque score may be accepted in a less susceptible patient who shows few signs of gingival bleeding or disease even when more plaque is present.

Some plaque formation is inevitable because it is not possible, or even desirable, to have a sterile mouth, and bacteria will always colonize the tooth surface and start to form a biofilm. The emphasis is thus on control of plaque, particularly by preventing it from becoming a mature and pathogenic biofilm, and in practice early plaque formation that is controlled by high levels of oral hygiene practices at frequent intervals may be largely undetectable by clinical assessment.

The process of achieving adequate plaque control requires the following:

• Oral hygiene methods that can effectively control plaque formation

• The ability of the patient to carry out these methods

• The motivation of the patient to implement these methods on a regular basis

Oral hygiene methods to control plaque formation

Toothbrushing

Toothbrushing

The major cause of periodontal disease is the presence of and effects of bacterial plaque. Most people remove, or attempt to remove, this biofilm with the aid of a toothbrush, and many methods of toothbrushing have been described. However, no one technique is necessarily better than another in plaque removal. Therefore, if plaque is removed effectively without causing trauma, any technique is acceptable. However, when a patient’s current plaque control methods are inadequate, then this is likely to require either modification or complete change in methods used.

There are two main types of toothbrushes—the manual toothbrush and the electric-operated or powered toothbrush (< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

The techniques for brushing teeth with manual or powered brushes are slightly different. A variety of techniques have been described for brushing with manual toothbrushes, and many of these are summarized in

Table 7.1 Toothbrushing techniques

| Technique | Principle | Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Bass technique | Sulcus cleaning | Circular vibratory motion starting at gingival margin |

| Stillman technique | Sulcus cleaning | Mini-scrub vibratory motion starting at gingival margin |

| Modified Stillman technique | Roll | Combination of Stillman technique concluding with roll of brush from gingival margin toward occlusal surface |

| Leonard technique | Vertical | “Up and down” brushing movement |

| Fones technique | Circular | Rotational movement on tooth surfaces |

| Rolling stroke | Circular/roll | Circular scrub of teeth when closed together; has been suggested to encourage children when starting toothbrushing |

| Scrub technique | Horizontal | “Back and forth” scrubbing movement |

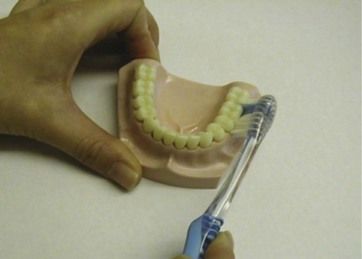

The most commonly taught method in practice is the modified Bass technique (

• The toothbrush is placed where the tooth and gum meet, starting on the outside surface of the teeth.

• The toothbrush should be placed at a 45-degree angle toward the gums (

• A circular motion should be used, cleaning two or three teeth at a time.

• The toothbrush should be moved slowly around mouth until the full arch has been cleaned.

• Once the outside of the teeth has been cleaned, then the inside of the teeth should be brushed using the same angulations and technique.

• Finally, the tops of the teeth can be cleaned using just the backward and forward motion.

• Once the lower teeth have been cleaned, the same technique should be applied to the upper teeth.

The main reasons for the popularity of this method are that it is specifically directed at cleaning the gingival margin (sulcus cleaning method) and is largely atraumatic to the tooth surfaces and gingival margins. On the other hand, some people find it technically difficult to do effectively, and in these cases an alternative sulcus cleaning technique may be preferred, such as the Stillman technique (mini-scrub).

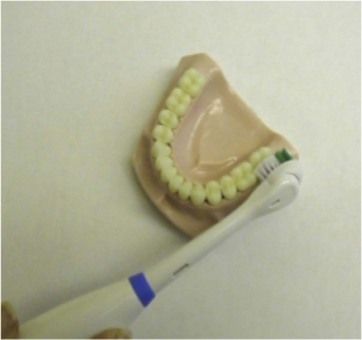

A person should do the following when using a powered toothbrush:

• Use the same placement and angulations as with manual toothbrush for sulcus cleaning, but instead of a circular motion, each tooth should have the brush placed on it for 3 or 4 sec and then move on to the next tooth, as shown in

• Once the outside of the teeth has been cleaned, brush the inside of the teeth using the same angulations and technique.

• Finally, the tops of the teeth should be brushed.

• Once the lower teeth have been cleaned, the same technique should be applied to the upper teeth.

There is no reliable evidence base on which to choose one method over another, recommend the amount of time toothbrushing should take, or recommend how often a toothbrush should be replaced. In the absence of an evidence base, it is still useful to have clear advice that c/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses