CHAPTER 6

Book Bone Flap

A real book is not one we read, but one that reads us.

—W. H. Auden

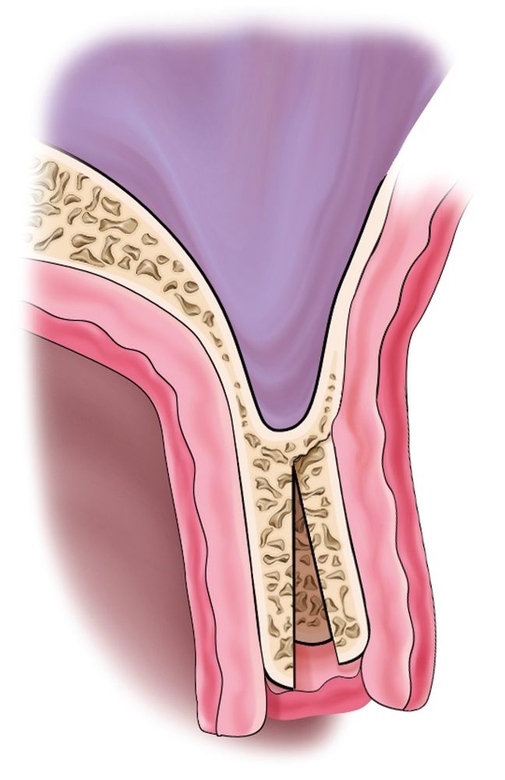

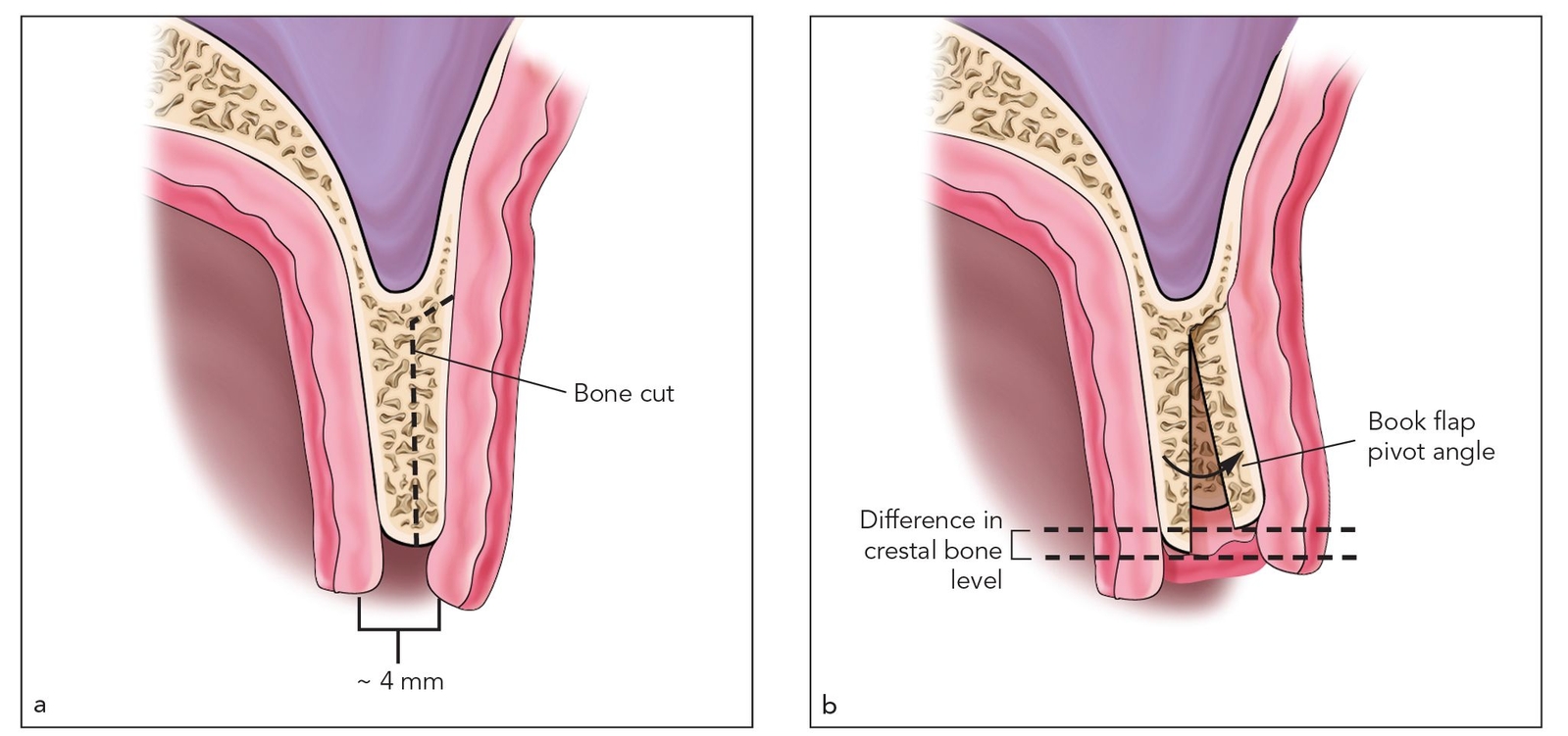

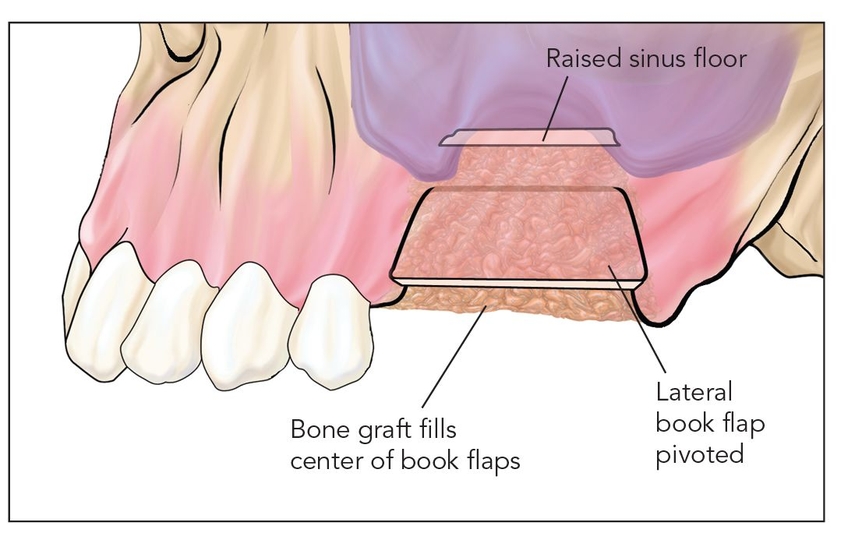

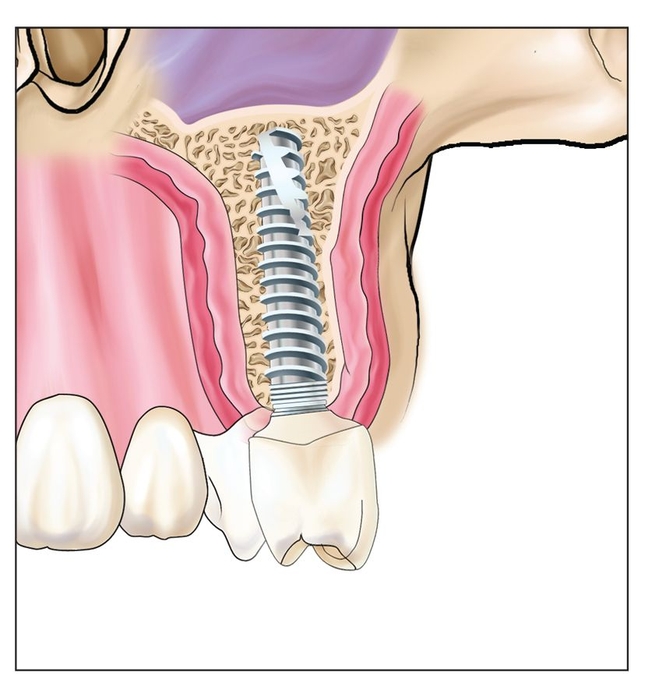

The osteoperiosteal flap procedure with the most utility, the most frequent application, and the simplest technique is the alveolar split graft known as the book bone flap.1 With this technique, the alveolus is split from the crest to the vestibule, without facial soft tissue detachment of the outfractured facial plate, to widen the alveolus.2 The book flap is generally used to increase alveolar width by 2 to 5 mm (Fig 6-1). The procedure can be used for expansion bone grafting for both immediate and delayed implant placement. The relatively soft bone of the maxilla is extremely amenable to the use of this technique provided that sufficient vertical bone is available. In the mandible, the book flap is more difficult to apply because of increased thickness of cortical bone, which often necessitates that an osteotomy be performed at the base of the alveolus to enable outfracture of the facial segment.

In either arch, a 3- or 4-mm alveolus can easily be expanded to 6 to 8 mm in width, a dimension often amenable to immediate implant placement, provided that there is adequate basal bone for implant stabilization. A book flap site is generally bordered by teeth. Maxillary anterior sites are especially amenable to this treatment, including canine sites where a canine eminence is desirable.

The one cautionary consideration with the book flap is the tendency to lose vertical height as the facial plate pivots to gain width. The greater the pivot from widening, the greater the reduction in vertical height of the facial plate. When a book flap is used in the esthetic zone, care should be taken to maintain the alveolar plane (of the facial plate) if possible, which requires a delayed implant placement strategy.

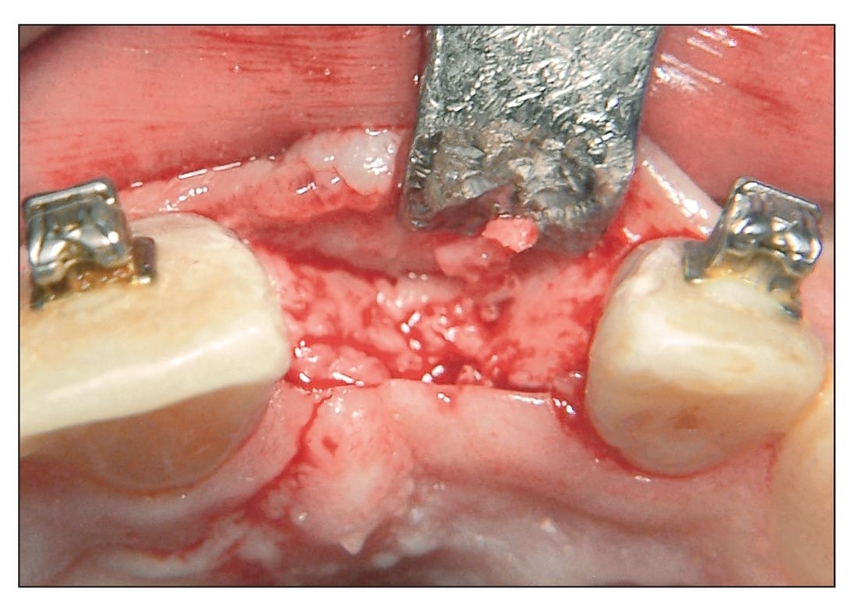

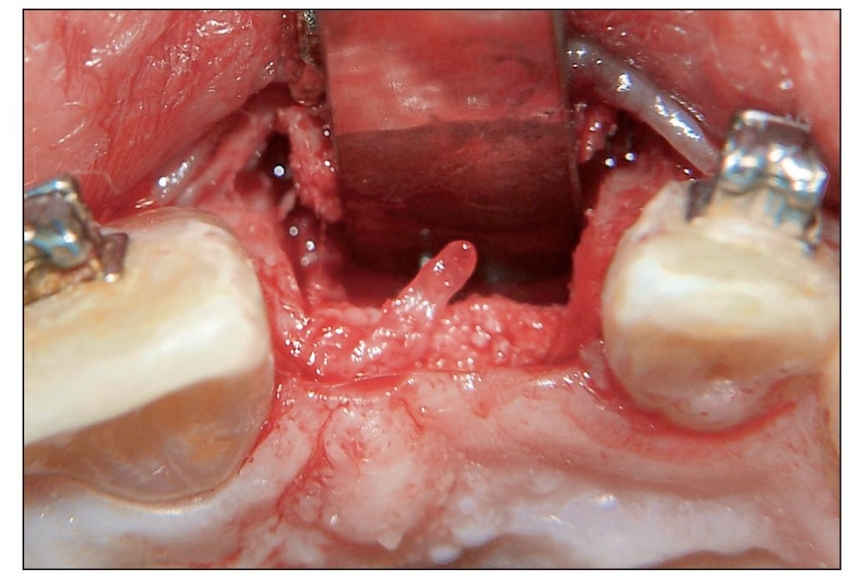

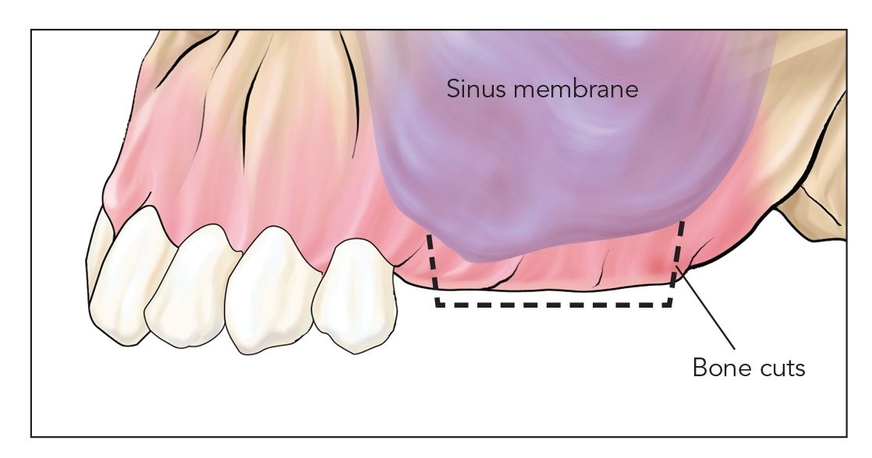

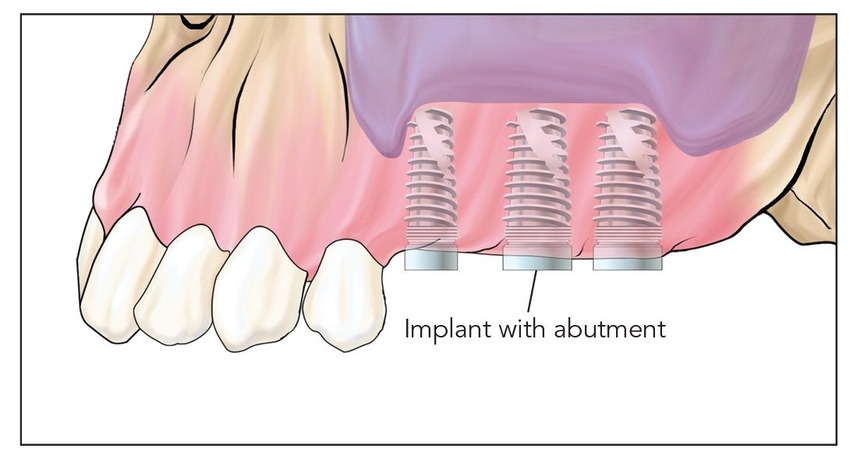

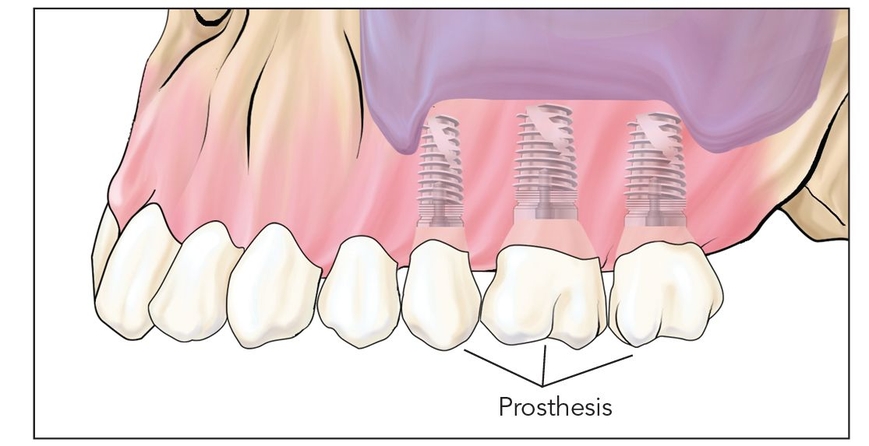

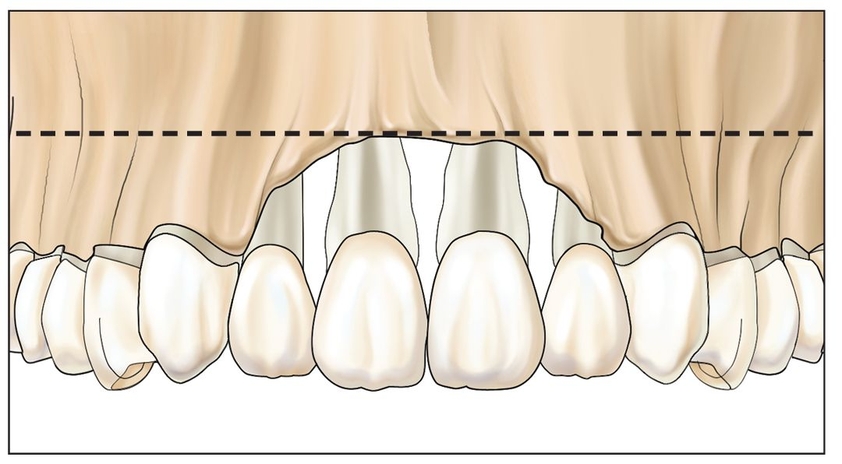

Figs 6-1a and 6-1b A narrow alveolus presenting for widening is minimally accessed by a crestal incision.

Fig 6-1c Without flap reflection, crestal and limiting vertical cuts are made.

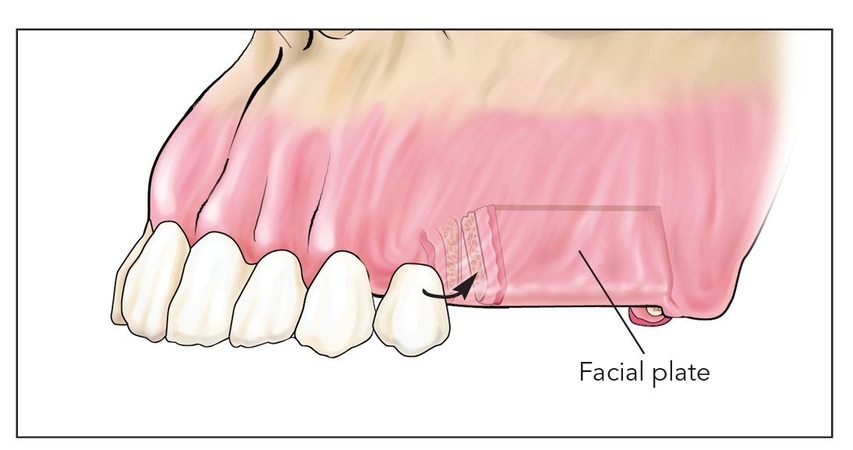

Fig 6-1d The facial plate is outfactured buccally, usually about 4 mm.

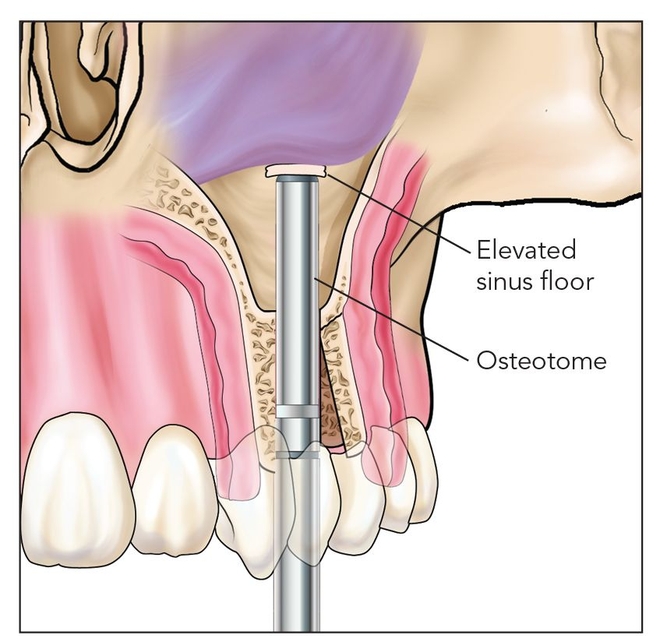

Fig 6-1e In the posterior maxilla, the book flap provides intra-alveolar access to intrude the sinus floor.

Fig 6-1f The sinus floor is raised front to back as an osteoperiosteal flap attached to sinus membrane.

Fig 6-1g Following ossification, dental implants are fixed and left to heal 4 months.

Fig 6-1h The final restoration gains adequate width and height.

Fig 6-1i The combined procedures established a mature facial plate as well as adequate bone for long-term osseointegration.

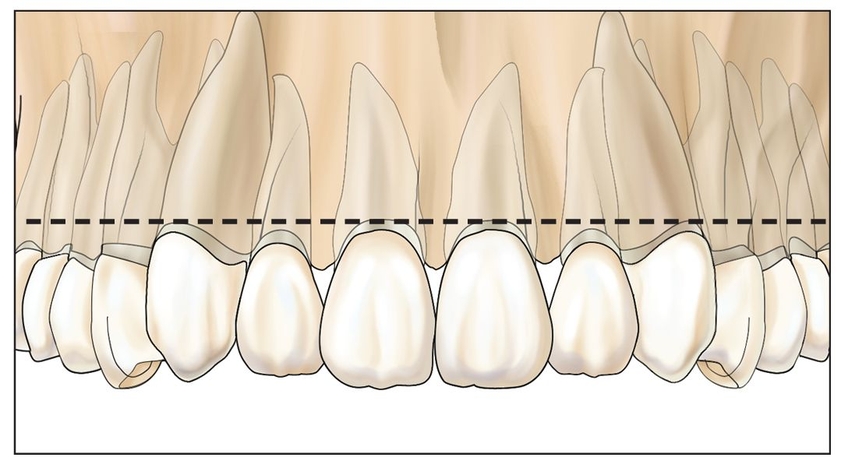

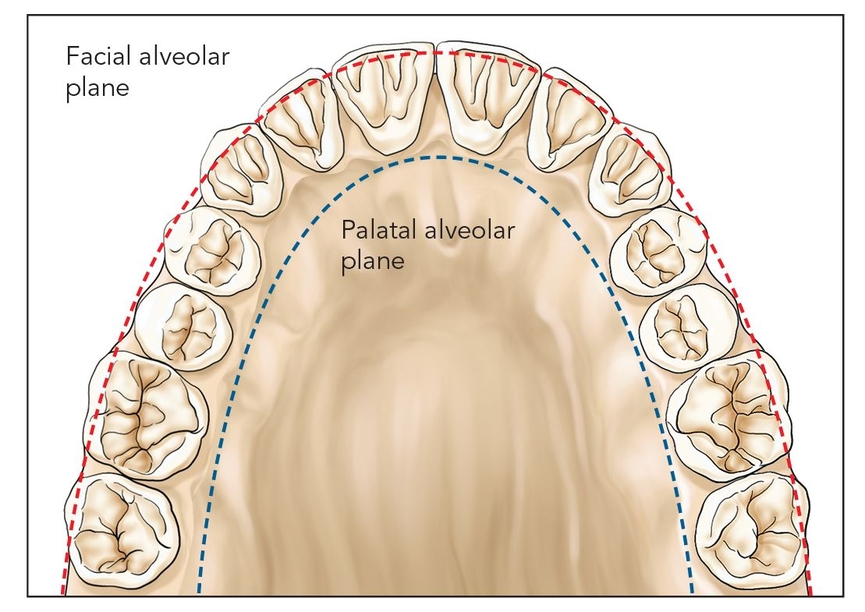

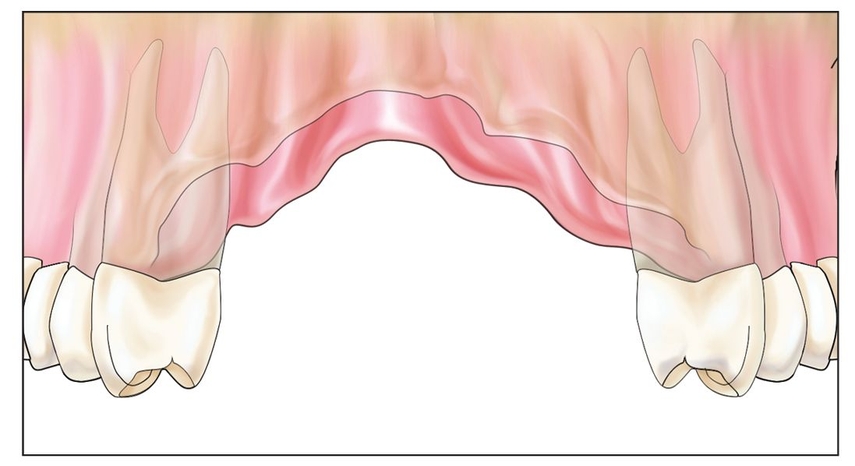

Figure 6-1b illustrates the pivot angle in regard to ridge widening and the loss of facial plate vertical projection as it relates to the alveolar plane. The alveolar plane can be thought of as a radiographic finding observed on panoramic radiographs and cephalograms. It is based on the relative bone level around the teeth, which is a composite of palatal and facial bone levels that overlap each other to create the alveolar plane. However, the alveolar plane conceptually may be thought of as two separate planes, the palatal and facial. When facial marginal bone loss occurs, these planes are no longer parallel, leading to a relative incongruity of these two planes (Fig 6-2).

Fig 6-2a The alveolar plane (black line) may be thought of as the crestal bone level around the arch.

Fig 6-2b Disturbances in the alveolar plane (black line) are especially noticeable with alveolar bone loss.

Fig 6-2c The alveolar plane is a composite of the facial alveolar (red line) and the palatal alveolar (blue line) planes.

Fig 6-2d Once teeth are lost, a defect of the alveolar plane is evident and the surgeon can visualize potential corrective measures.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses