CHAPTER 55 Prescription Writing and Drug Regulations

PRESCRIPTION

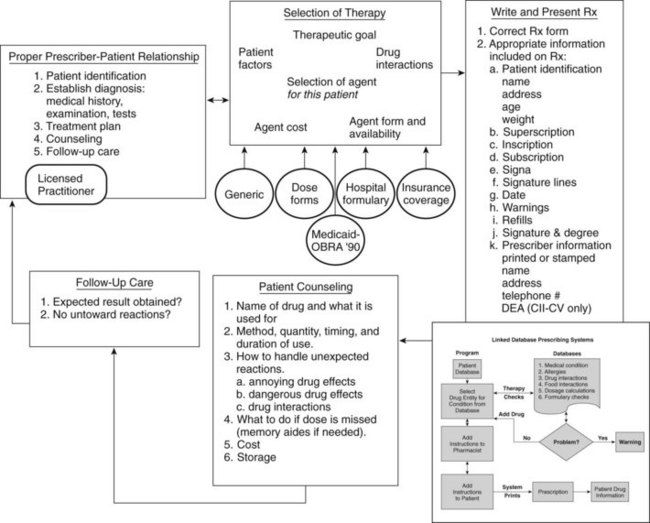

The writing of a prescription is one step in many that must be properly performed to initiate a course of therapy (Figure 55-1). This process starts with establishing a proper prescriber-patient relationship, which includes patient identification, proper diagnostic procedures, presentation and discussion of a treatment plan to the patient, availability of counseling, and follow-up care. These fundamental concepts have been reasserted more recently by the medical profession with respect to online prescribing for patients who are unknown to the practitioner. A prescription is prima facie evidence in court that such a relationship exists. Selection of therapy requires a multitude of factors to be considered: factors related to the patient (e.g., has difficulty swallowing tablets) and the therapeutic goal (cure or symptom control); evaluation of drug interactions; recognition of the various relationships among the patient, prescriber, and insurance companies and governmental bodies (that may establish guidelines or limits on payment for medications); and the medication costs and whether the patient can afford to buy it. Prescribing outside the proper prescriber-patient relationship is unprofessional conduct.

Prescribing should be done in a thoughtful and deliberate way, and the conditions for error-free prescribing must be ensured. In 1999, The Institute of Medicine report “To Err is Human” documented an increasing frequency of medical errors.9 The report analyzed the nature of errors and categorized them into slips, lapses, and mistakes. Slips and lapses occur when the prescriber knows the correct procedure, but fails to perform it properly. Mistakes result from incorrect understanding of the correct course of action.

Legal Categories of Drugs

As a result of legislative changes during the 1990s (Table 55-1), several additional sources of treatments have become more available. Dietary supplements may contain “dietary ingredients,” which can include vitamins, minerals, herbs, amino acids, enzymes, organ tissues, metabolites, extracts, or concentrates. These products must be labeled as dietary supplements. The manufacturer is responsible for (1) truthful information, (2) nonmisleading information, and (3) ensuring that the dietary ingredients in the supplements are safe. Manufacturers do not need to register with the FDA or obtain FDA approval. Complementary and alternative medical approaches may use “biologicals,” which can include herbal remedies, special diets, or food products used for therapy. Herbs are defined as plants or plant products that produce or contain chemicals that act on the body.

| LAW | EFFECT |

|---|---|

| Pure Food and Drug Act 1906 (Wiley Act) | Prohibited mislabeling and adulteration of drugs26 |

| Opium Exclusion Act of 1909 | Prohibited importation of opium |

| Amendment (1912) to the Pure Food and Drug Act | Prohibited false or fraudulent advertising claims |

| Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914 | Established regulations for use of opium, opiates, and cocaine (marijuana added in 1937) |

| Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 | Required that new drugs be safe and pure (but did not require proof of efficacy); enforcement by FDA27 |

| Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951 | Vested in the FDA the power to determine which products could be sold without prescription |

| Kefauver-Harris Amendments (1962) to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act | Required proof of efficacy and safety for new drugs and for drugs released since 1938; established guidelines for reporting information about adverse reactions, clinical testing, and advertising of new drugs |

| Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (1970), Controlled Substances Act, as amended | Outlined strict controls in the manufacture, distribution, and prescribing of habit-forming drugs; established programs to prevent and treat drug addiction32 |

| Orphan Drug Amendments of 1983 | Amended Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938, providing incentives for the development of drugs to treat conditions suffered by <200,000 patients in the United States.33 |

| Drug Price Competition and Patent Restoration Act of 1984 (Waxman-Hatch Act) | Abbreviated NDA for generic drugs; required bioequivalence data; patent life extended by amount of time delayed by FDA review process; cannot exceed 5 extra yr or extend >14 yr post-NDA approval; authorized abbreviated NDA |

| Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 | Deepened governmental involvement in prescription writing through legislation relating to “best discount prices,” rebates, formularies, and pharmacy reimbursements; placed restrictions on payment for prescriptions for barbiturates and benzodiazepines |

| Generic Drug Debarment Act of 1991 and the Food, Drug, Cosmetic and Device Enforcement Amendment of 1991 | Increased penalties for abuses of generic drug regulations |

| 1992 Expedited Drug Approval Act | Allowed accelerated FDA approval for drugs of high medical need; required detailed postmarketing patient surveillance |

| 1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act | Required manufacturers to pay user fees for certain NDAs; FDA states review time for new chemical entities has decreased from 30 mo in 1992 to 20 mo in 199431 |

| 1994 Dietary Supplements and Health Education Act | Required dietary supplement manufacturers to ensure that a dietary supplement is safe before it is marketed; FDA is responsible for taking action against any unsafe dietary supplement product after it reaches the market; generally, manufacturers do not need to register with FDA or get FDA approval before producing or selling dietary supplements; manufacturers must ensure that product label information is truthful and not misleading25 |

| North American Free Trade Act (1994) and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1948), World Trade Organization (1995) | Necessitated harmonization of pharmacopeias and drug regulations between trading partners |

| 1996 Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act (HIPAA) | Standardized third-party payment for medical treatment and increased confidentiality and privacy for patient information maintained in medical databases20 |

| 1997 FDA Modernization Act | Replaced “legend” with label “Rx only”; allowed manufacturer to discuss off-label uses of drugs with practitioners; revised accelerated track approval for drugs that treat life-threatening disorders; made provisions for pediatric drug research; revised interaction of agency with individuals doing clinical trials6 |

| 2005 Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act | Establishes new regulations for the sale of ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine that differ from the Control Substance V regulations by not requiring sale in a pharmacy |

| U.S. Troop Readiness, Veterans’ Care, Katrina Recovery, and Iraq Accountability Appropriations Act of 2007 | Established requirement for the use of tamper-resistant written prescriptions for Medicaid prescription reimbursement. Prescriptions must have three tamper-resistant features |

NDA, New Drug Application.

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine sponsors many projects to investigate the potential therapeutic value of treatments such as St. John’s wort, shark cartilage, and glucosamine. The goal is to determine whether these treatments can aid in the treatment of various disorders. This Center is also concerned with assessing the value of nondrug therapies and nontraditional medical systems such as acupuncture, Eastern medicine, and homeopathic medicine. The FDA can provide guidelines for the therapeutic claims made for these various products through the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, whose role is primarily educational. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) has developed a Dietary Supplement Verification (DSV) Program. For a dietary supplement to bear the USP-DSV seal, it must include its ingredients on the label; indicate the strength and amounts of ingredients; prove that the product is shown to be absorbable when taken; and document that it has been screened for heavy metals, microbes, and pesticides and been manufactured in safe, sanitary, and controlled conditions. (See Chapter 56 for a more complete review of herbal products and alternative medicine.)

Drug Names and Generic Substitution

As discussed in Chapter 3, any drug may be identified by more than one designation in various references, texts, and package inserts. Of special interest here are nonproprietary and proprietary names. The nonproprietary name is also referred to as the generic name. This name is selected by the U.S. Adopted Names Council. The steady increase in the number of new drugs and the marketing of existing drugs by different manufacturers are making similarities between different drug names an increasing challenge. The practitioner must be vigilant in prescribing the correct agent and spelling drug names correctly. Because, with few exceptions, individual drugs have only one nonproprietary name, it is this name by which the drug is primarily identified. Nonproprietary names may differ among countries, however. The same agent may also have many proprietary or trade names, which are given to it by the various manufacturers or marketers to identify their brand of the drug. In advertisements and labeling with the trade name, the nonproprietary name of the drug must also be prominently identified.

In recent years, governmental regulatory agencies have had a strong tendency to encourage or mandate the prescription and dispensation of drugs by nonproprietary name.15 The principal motivation for these regulations is to control rapidly increasing drug costs. Currently, all states and the District of Columbia have repealed their existing antisubstitution laws and replaced them with drug substitution laws permitting or, in some states, requiring the pharmacist to dispense generic drugs (preparations containing the same active chemicals in identical amounts, but sold under the common nonproprietary name), unless specifically prohibited by the prescriber. Also, the federal government has instituted “maximum allowable cost” programs in an effort to contain the cost of prescription drugs to the consumer by limiting prescription by proprietary name. These programs require the prescriber to certify the necessity of prescribing a specific brand of drug rather than its nonproprietary counterpart. According to the FDA, the savings may range from 30% to 80%.28

Equivalence: Chemical, Pharmaceutical, Biologic, and Therapeutic

If two brands of the same drug are to be considered for substitution, the basis for identifying them as equivalent must be carefully defined.12 Drug products that contain the same amounts of the same active ingredients in the same dosage forms and meet current official compendium standards are considered chemical equivalents. Pharmaceutical equivalents are drug products that contain the same amounts of the same therapeutic or active ingredients in the same dosage form and meet standards based on the best currently available technology. This description means that pharmaceutical equivalents are formulated identically and must pass certain laboratory tests for equivalent activity, including dissolution tests when appropriate, by standards set for various classes of drugs.

To facilitate the wider use of generic drugs, the FDA has published a list of all FDA-approved drugs that it regards as therapeutically equivalent, entitled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (also known as the Orange Book).16 This source can be used as a guide to identifying less expensive generic alternatives that pharmacists can substitute for a brand name product designated the “reference listed drug,” that is, the innovator drug. This list indicates drugs that are considered therapeutically equivalent (termed a positive formulary), designated with a rating beginning with the letter A; drugs that may not be therapeutically equivalent (termed a negative formulary), designated with a starting letter B; and drugs about which the agency has not yet made a determination (blanks). The FDA’s policy is to consider pharmaceutically equivalent drugs as therapeutically equivalent unless scientific evidence to the contrary exists. In the Orange Book (available on the Internet5), the reference-listed drug, therapeutically equivalent rating, and generic drug rating are provided in tabular form. If a generic oral dosage form preparation is considered therapeutically equivalent, it is given the designation of AB (the second letter, B in this case, refers to the class of dose form). At the time of this writing, 96% of ibuprofen tablets were judged AB, 100% of diazepam tablets were AB, and all erythromycin ethyl succinate suspensions were considered AB.

Component Parts of the Prescription

Several sources of drug information should be available during selection of drug therapy (also discussed in Chapter 3). Good sources for identifying the drug, dosage form, and dose include The Physicians’ Desk Reference, Facts and Comparisons, Mosby’s Drug Reference for Health Professions, and ePocrates Rx. In addition, it is valuable to have a compilation of drug interactions available to screen for possible adverse interactions. A book such as Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation by Briggs and colleagues2 is helpful when a course of therapy is being planned for women of childbearing potential and for pregnant or nursing women. The American Pharmacists Association’s Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs may be useful if the practitioner is uncertain whether an OTC drug might affect therapy. References on herbal drugs and dietary supplements may also be useful (see Chapter 56).

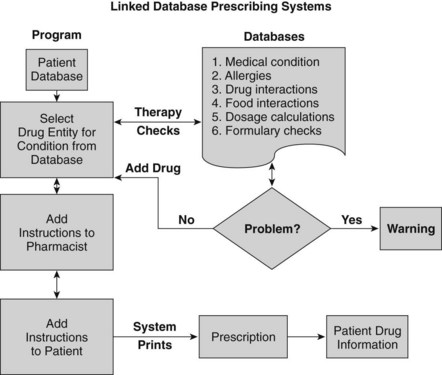

Additional sources of drug information are available as computer software programs, compact disks, and personal digital assistant programs and on the Internet. Electronic resources can have advantages if the text is accompanied by a sophisticated search engine. An innovation in prescribing is the concept of “linked database prescribing” (Figure 55-2). This type of system has the potential to reduce several sources of prescribing errors, such as poor handwriting, selection of the wrong drug name (selection is based on therapeutic classification), nonexistent product strengths and dosage forms, orders for drugs to which patients are allergic, and therapeutic incompatibilities. Other errors such as dosing and patient instruction errors could also be reduced by appropriately designed systems.

The transcription, or signature—from the Latin signa, meaning “label” or “let it be labeled,” and indicated on the prescription by “Label:” or “Sig:”—is the prescriber’s directions to the patient that appear on the medicine container. At one time, such directions were uniformly written in Latin, but modern practice is to use English. Latin abbreviations are still used by many clinicians in prescriptions and progress notes to save time (Table 55-2); however, such gains are minor in general dental practice and may contribute to prescription errors (e.g., “q4h” instead of “qid” represents a 50% dosage increase). Figure 55-3 depicts the same signature for an analgesic medication, one written entirely in English and the other written in Latin abbreviations. Items written in the transcription are transferred onto the prescription bottle label by the pharmacist, so they should be complete but concise.

| ABBREVIATION | LATIN | ENGLISH |

|---|---|---|

| ad lib. | ad libitum | at pleasure |

| a.c. | ante cibum | before meals |

| aq. | aqua | water |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses