General Principles of Periodontal Surgery

Outpatient Surgery

Patient Preparation

Reevaluation After Phase I Therapy.

Premedication.

For patients who are not medically compromised, the value of administering antibiotics routinely for periodontal surgery has not been clearly demonstrated.29 However, some studies have reported reduced postoperative complications, including reduced pain and swelling, when antibiotics are given before periodontal surgery and continued for 4 to 7 days after surgery.4,12,21,32

The prophylactic use of antibiotics in patients who are otherwise healthy has been advocated for bone-grafting procedures and purported to enhance the chances of new attachment. Although the rationale for such use appears logical, no research evidence is available to support it. In any case, the risks inherent to the administration of antibiotics should be evaluated together with the potential benefits. Other presurgical medications include the administration of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as ibuprofen (e.g., Motrin) 1 hour before the procedure as well as the use of a mouthrinse with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate (Peridex, PerioGard).38

Precautions to be taken with medically compromised patients are discussed in Chapter 37.

Smoking.

The deleterious effect of smoking on the healing of periodontal wounds has been amply documented20,33,43 (see Chapter 10). Patients should be clearly informed of this fact and asked to quit smoking completely or to at least stop smoking for a minimum of 3 to 4 weeks after the procedure. For patients who are unwilling to follow this advice, an alternate treatment plan that does not include more sophisticated techniques (e.g., regenerative, mucogingival, aesthetic) should be considered.

Emergency Equipment

The most common emergency is syncope, which is a transient loss of consciousness caused by a reduction in cerebral blood flow. The most common causes of syncope are fear and anxiety. Syncope is usually preceded by a feeling of weakness, and then the patient develops pallor, sweating, coldness of the extremities, dizziness, and a slowing of the pulse. The patient should be placed in a supine position with the legs elevated; tight clothes should be loosened, and a wide-open airway should be ensured. The administration of oxygen is also useful. Unconsciousness may persists for a few minutes. A history of previous syncopal attacks during dental appointments should be explored before treatment is begun; if these are reported, extra efforts to relieve the patient’s fear and anxiety should be made. The reader is referred to other texts for a complete analysis of this important topic.3

Sedation and Anesthesia

For individuals with mild to moderate anxiety, oral administration of a benzodiazepine can be effective to decrease anxiety and to produce a level of relaxation. The oral administration of a sedative agent can be more effective than inhalation anesthesia, because the level of sedation achieved may be more profound. Disadvantages of oral sedative administration include incomplete recovery, an inability to control the level of sedation, and a prolonged period of impaired sensory and motor skills. A variety of benzodiazepine agents are available for oral administration (see Chapter 36).

The intravenous administration of a benzodiazepine, either alone or in combination with other agents, can be used to achieve a greater level of sedation in individuals with moderate to severe levels of anxiety. Furthermore, the onset of action of intravenous sedation is almost immediate, and the level of sedation can be titrated on an individual basis to the desired effect. The recovery period depends on the half-life of the agent used and the amount given. The operator should receive formal training in the techniques of sedation; this often is required by law. A thorough understanding of the indications, contraindications, and risks of these agents is required.3 The reader is referred to Chapter 36 and other texts for a more detailed discussion of conscious sedation modalities, agents, and techniques.26

Tissue Management

1. Operate gently and carefully. In addition to being most considerate to the patient, this is also the most effective way to operate. Tissue manipulation should be precise, deliberate, and gentle. Thoroughness is essential, but roughness must be avoided, because it produces excessive tissue injury, causes postoperative discomfort, and delays healing.

2. Observe the patient at all times. It is essential to pay careful attention to the patient’s reactions. Facial expressions, pallor, and perspiration are distinct signs that may indicate that the patient is experiencing pain, anxiety, or fear. The physician’s responsiveness to these signs can be the difference between success and failure.

3. Be certain that the instruments are sharp. Instruments must be sharp to be effective; successful treatment is not possible without sharp instruments. Dull instruments inflict unnecessary trauma as a result of poor cutting and excessive force applied to compensate for their ineffectiveness. A sterile sharpening stone should be available on the operating table at all times.

Hemostasis

Excessive hemorrhaging after initial incisions and flap reflection may be caused by the laceration of venules, arterioles, or larger vessels. Fortunately, the laceration of medium or large vessels is rare, because incisions near highly vascular anatomic areas (e.g., the posterior mandible [the lingual and inferior alveolar arteries], the posterior mid-palatal regions [the greater palatine arteries]) are avoided by incision and flap procedures. Proper design of the flaps, which takes these areas into consideration, avoids accidents (see Chapter 53). However, even when all anatomic precautions are taken, it is possible to cause bleeding from medium or large vessels, because anatomic variations do occur and may result in inadvertent laceration. If a medium or large vessel is lacerated, a suture around the bleeding end may be necessary to control hemorrhage. Pressure should be applied through the tissue to determine the location that will stop blood flow in the severed vessel. A suture can then be passed through the tissue and tied to restrict blood flow. Excessive bleeding from a surgical wound may also result from incisions across a capillary plexus. Minor areas of persistent bleeding from capillaries can be stopped by applying cold pressure to the site with moist gauze (soaked in sterile ice water) for several minutes.

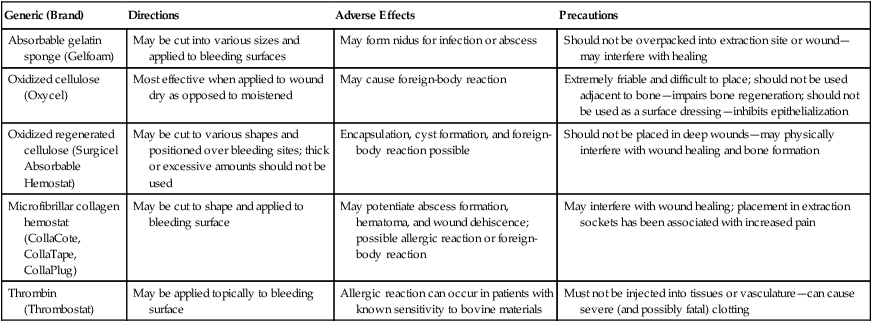

For a slow constant blood flow and for oozing, hemostasis may be achieved with hemostatic agents. Absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam), oxidized cellulose (Oxycel), oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel Absorbable Hemostat), and microfibrillar collagen hemostat (CollaCote, CollaTape, CollaPlug) are useful hemostatic agents for the control of bleeding in capillaries, small blood vessels, and deep wounds (Table 55-1).

TABLE 55-1

| Generic (Brand) | Directions | Adverse Effects | Precautions |

| Absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) | May be cut into various sizes and applied to bleeding surfaces | May form nidus for infection or abscess | Should not be overpacked into extraction site or wound—may interfere with healing |

| Oxidized cellulose (Oxycel) | Most effective when applied to wound dry as opposed to moistened | May cause foreign-body reaction | Extremely friable and difficult to place; should not be used adjacent to bone—impairs bone regeneration; should not be used as a surface dressing—inhibits epithelialization |

| Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel Absorbable Hemostat) | May be cut to various shapes and positioned over bleeding sites; thick or excessive amounts should not be used | Encapsulation, cyst formation, and foreign-body reaction possible | Should not be placed in deep wounds—may physically interfere with wound healing and bone formation |

| Microfibrillar collagen hemostat (CollaCote, CollaTape, CollaPlug) | May be cut to shape and applied to bleeding surface | May potentiate abscess formation, hematoma, and wound dehiscence; possible allergic reaction or foreign-body reaction | May interfere with wound healing; placement in extraction sockets has been associated with increased pain |

| Thrombin (Thrombostat) | May be applied topically to bleeding surface | Allergic reaction can occur in patients with known sensitivity to bovine materials | Must not be injected into tissues or vasculature—can cause severe (and possibly fatal) clotting |

Periodontal Dressings (Periodontal Packs)

In most cases, after the surgical periodontal procedures are completed, the area is covered with a surgical pack. In general, dressings have no curative properties; they assist healing by protecting the tissue rather than providing “healing factors.” The pack minimizes the likelihood of postoperative infection and hemorrhage, facilitates healing by preventing surface trauma during mastication, and protects the patient from pain induced by contact of the wound with food or with the tongue during mastication. (For a complete literature review on this subject, see the article by Sachs and colleagues.37)

Zinc Oxide–Eugenol Packs.

Packs that are based on the reaction of zinc oxide and eugenol include the Wondr Pak, which was developed by Ward46 in 1923, and several other packs that use modified forms of Ward’s original formula. The addition of accelerators such as zinc acetate gives the dressing a better working time.

Noneugenol Packs.

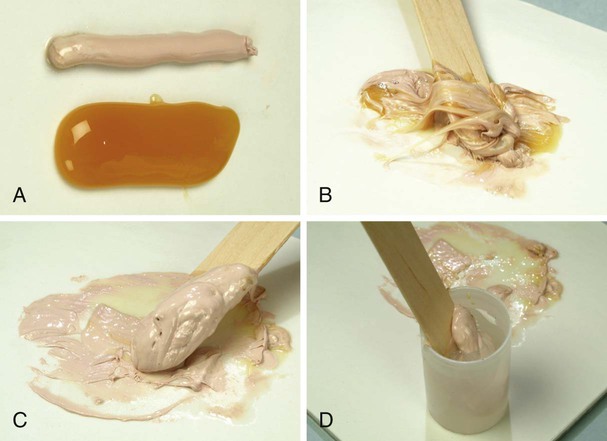

The reaction between a metallic oxide and fatty acids is the basis for the Coe-Pak, which is the most widely used dressing in the United States. This is supplied in two tubes, the contents of which are mixed immediately before use until a uniform color is obtained. One tube contains zinc oxide, an oil (for plasticity), a gum (for cohesiveness), and Lorothidol (a fungicide); the other tube contains liquid coconut fatty acids that have been thickened with colophony resin (or rosin) and chlorothymol (a bacteriostatic agent).37,40 This dressing does not contain asbestos or eugenol, thereby avoiding the problems associated with these substances.

Other noneugenol packs include cyanoacrylates6,19,24 and tissue conditioners (methacrylate gels).2 However, these are not in common use.

Retention of Packs.

Periodontal dressings are usually kept in place mechanically by interlocking in interdental spaces and joining the lingual and facial portions of the pack. In isolated teeth or when several teeth in an arch are missing, retention of the pack may be difficult. Numerous reinforcements and splints and stents for this purpose have been described.17,18,47 The placement of dental floss tied loosely around the teeth enhances retention of the pack.

Antibacterial Properties of Packs.

Improved healing and patient comfort with less odor and taste6 have been obtained by incorporating antibiotics into the pack. Bacitracin,5 oxytetracycline (Terramycin),13 neomycin, and nitrofurazone have been tried, but all of these may produce hypersensitivity reactions. The emergence of resistant organisms and opportunistic infections has been reported.35 The incorporation of tetracycline powder into the Coe-Pak is generally recommended, particularly when long and traumatic surgeries are performed.

Preparation and Application of Dressing.

The Coe-Pak is prepared by mixing equal lengths of paste from tubes that contain the accelerator and the base until the resulting paste is a uniform color (Figure 55-1, A to C). A capsule of tetracycline powder can be added at this time. The pack is then placed in a cup of water at room temperature (Figure 55-1, D). After 2 to 3 minutes, the paste loses its tackiness, and it can be handled and molded; it remains workable for 15 to 20 minutes. The working time can be shortened by adding a small amount of zinc oxide to the accelerator (pink paste) before spatulating.

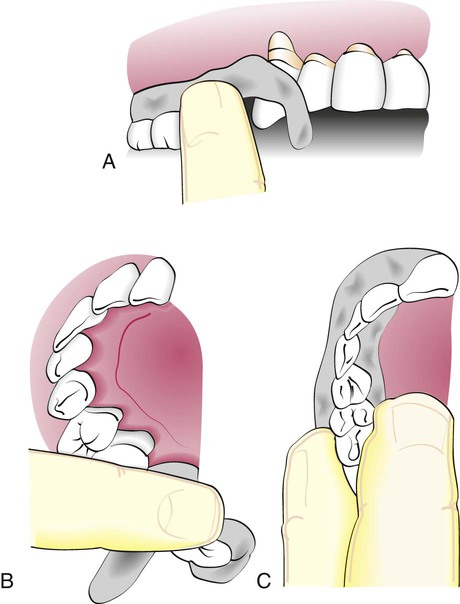

The pack is then rolled into two strips that are approximately the length of the treated area. The end of one strip is bent into a hook shape and fitted around the distal surface of the last tooth to approach that tooth from the distal surface (Figure 55-2, A). The remainder of the strip is brought forward along the facial surface to the midline and gently pressed into place along the gingival margin and interproximally. The second strip is applied from the lingual surface. It is joined to the pack at the distal surface of the last tooth and then brought forward along the gingival margin to the midline (Figure 55-2, B). The strips are joined interproximally by applying gentle pressure on the facial and lingual surfaces of the pack (Figure 55-2, C). For isolated teeth separated by edentulous spaces, the pack should be made continuous from tooth to tooth to cover the edentulous areas (Figure 55-3).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses