CHAPTER 5 Introduction to Autonomic Nervous System Drugs

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the endocrine system are the major regulatory systems for controlling homeostatic functions. These two systems collectively regulate and coordinate the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, renal, reproductive, metabolic, and immunologic systems. Drugs that alter the activity of either the ANS or the endocrine system often exhibit multiple actions and side effects. This chapter introduces the pharmacology of the ANS; the endocrine system and drugs are reviewed in Chapters 34 through 37. An understanding of the pharmacology of agents affecting the ANS rests on two basic foundations: a knowledge of the structural and functional organization of the ANS, and an understanding of where certain neurotransmitters are located and how these neurotransmitters affect cellular function.

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

The ANS, also referred to as the visceral, vegetative, or involuntary nervous system, regulates the function of smooth muscle, the heart, and certain secretory glands. These structures possess intrinsic mechanisms that allow them to function in the absence of neuronal input, but the ANS contributes a regulatory and coordinating function. Most of our knowledge of the ANS is restricted to efferent functions; much less is known about the afferent limb. Sensory afferent fibers carry impulses that are received and organized centrally, often at an unconscious level. A person is unaware of impulses generated at the baroreceptors, although these impulses may trigger a generalized body response, such as a reflex decrease in blood pressure, which the person may sense. It has been estimated that approximately 80% of the vagus nerve consists of primary afferent fibers and that the effects of certain drugs (e.g., opioids) may be mediated in part by altering autonomic sensory inputs.16,30 Nevertheless, most currently available ANS drugs influence efferent activity.

Anatomy

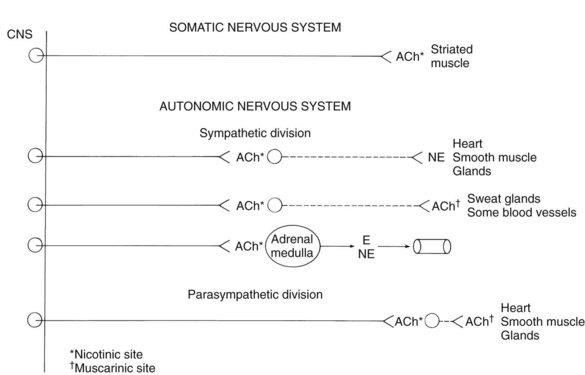

The structural organization of the efferent arm of the ANS differs from that of the somatic nervous system. Somatic efferent fibers originate from cell bodies located in the central nervous system (CNS) and innervate skeletal (striated) muscle without intervening synapses (Figure 5-1). In contrast, the ANS consists of a two-neuron system in which preganglionic nerves emanating from cell bodies in the cerebrospinal axis synapse with postganglionic nerves originating in autonomic ganglia outside the CNS. The ANS is divided into two parts on the basis of the anatomic characteristics of each division. The sympathetic division includes nerve pathways that originate in the thoracolumbar regions of the spinal cord, whereas the parasympathetic division includes nerve pathways from the craniosacral regions of the cerebrospinal axis.

Sympathetic nervous system

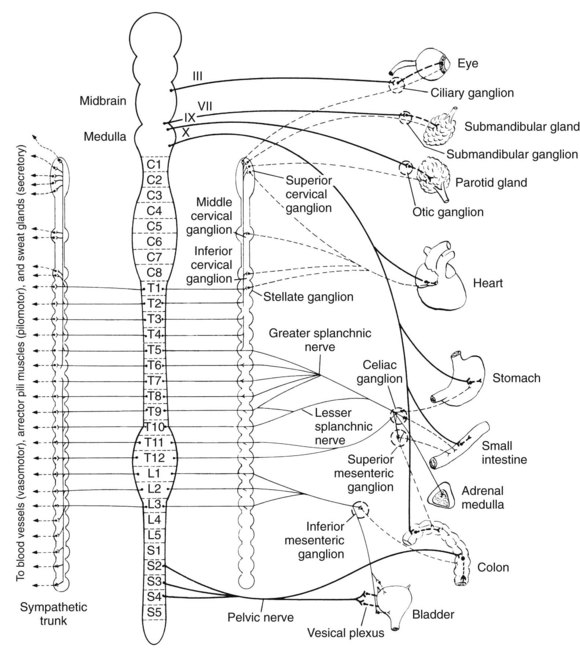

The organizational anatomy of the two divisions of the ANS is shown in greater detail in Figure 5-2. The sympathetic division originates from neurons with cell bodies located in the intermediolateral columns of the spinal cord, extending from the first thoracic to the third lumbar segments. The myelinated preganglionic fibers emerge with the ventral roots of the spinal nerves and synapse with second neurons in one of three possible types of ganglia: paravertebral (vertebral or lateral), prevertebral, or terminal. The paravertebral ganglia are composed of 22 pairs of ganglia lying on either side of the spinal cord and connected to each other by communicating nerve fibers. The superior cervical ganglia (the topmost pair) innervate structures in the head and neck, including the submandibular glands, whereas the superior, middle, and inferior cervical ganglia all innervate the heart. The prevertebral ganglia are located in the abdomen and pelvis and include the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric, which innervate the stomach, the small intestine, and the colon. The few terminal ganglia lie near the organs they innervate, principally the urinary bladder and rectum.

Functional Characteristics

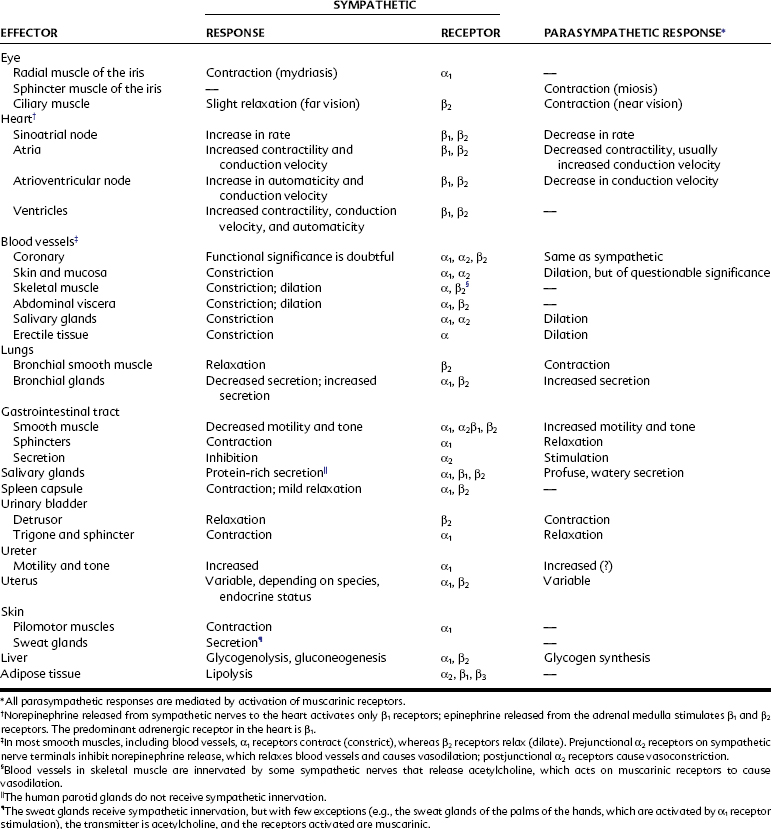

Most organs are dually innervated by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, such as most salivary glands and the heart, lungs (bronchial muscle), and abdominal and pelvic viscera, whereas other organs receive innervation from only one division. The sweat glands, adrenal medulla, piloerector muscles, and most blood vessels receive innervation from only the sympathetic nervous system. The parenchyma of the parotid, lacrimal, and nasopharyngeal glands are supplied only with parasympathetic nerves. Table 5-1 lists the organs to which nerve fibers of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems are distributed, the effects of stimulation of these nerves, and the autonomic receptors that are activated by neurotransmitters released from autonomic nerves.

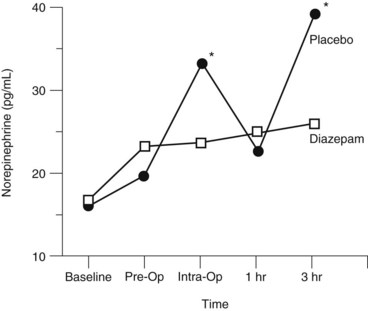

The anatomic and functional characteristics of the two divisions of the ANS show that there are striking differences between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Cannon11 was the first to recognize that the sympathetic nervous system is capable of producing the kind of widespread and massive response that would enable an organism confronted with a stressor (e.g., pain, asphyxia, or strong emotions) to mount an appropriate response (“fright, fight, or flight”). Controlled clinical trials in dental patients indicate that oral surgical procedures constitute physiologically significant stressors for stimulating the sympathetic nervous system, with noticeable increases in circulating norepinephrine concentrations observed in patients during surgery and with the development of postsurgical pain (Figure 5-3). The stress of oral surgery is mediated by the CNS because drugs that reduce anxiety (e.g., diazepam) also reduce the sympathetic response to surgical stress and postoperative pain.15,19 The parasympathetic division is primarily concerned with the protection, conservation, and restoration of bodily resources. These differences in function are subserved by some of the anatomic characteristics that have already been mentioned, including the involvement of the adrenal medulla and the high ratio of postganglionic to preganglionic nerves in the sympathetic, but not the parasympathetic, nervous system.

NEUROTRANSMITTERS

Location of Adrenergic and Cholinergic Junctions

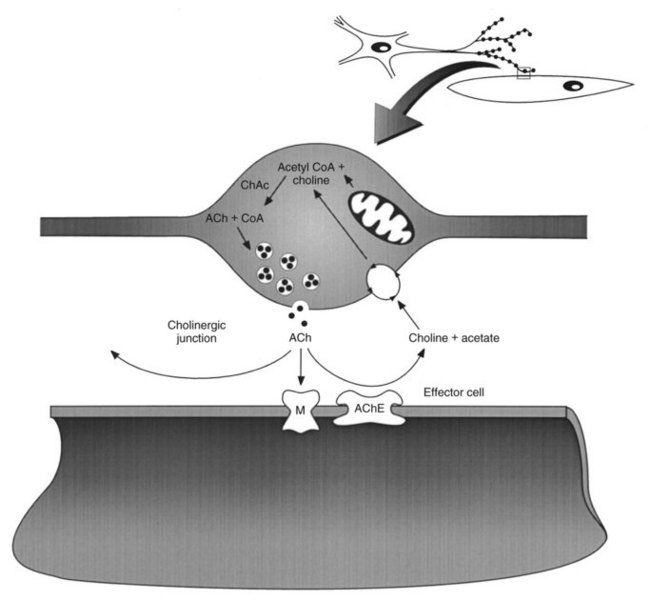

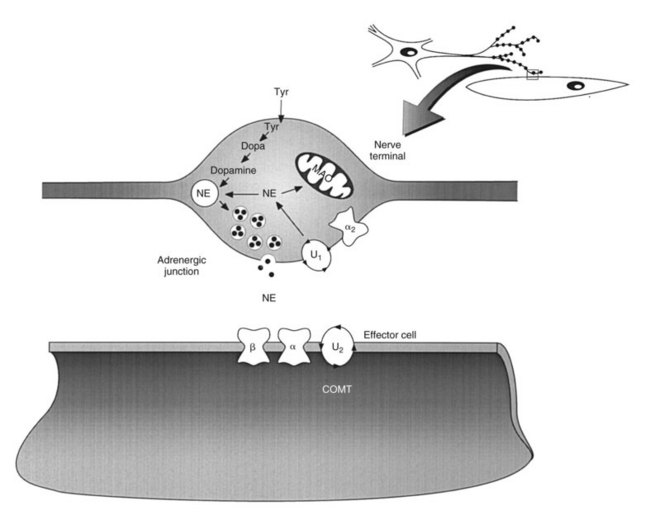

Figure 5-1 shows the sites at which the neurotransmitters acetylcholine and norepinephrine and the hormone epinephrine act as chemical mediators. With the exception of effectors (smooth muscle, the heart, and secretory glands) that are innervated by postganglionic sympathetic nerves where the neurotransmitter is norepinephrine, all other sites are innervated by cholinergic nerves, including the ganglia of the ANS, the adrenal medulla, a few effectors of the sympathetic nervous system, and all the effectors of the parasympathetic nervous system. At cholinergic junctions, cholinergic nerves release acetylcholine, which acts on cholinergic receptors to produce an effect. These ubiquitous cholinergic receptors are composed of two structurally unrelated types, called muscarinic and nicotinic, which are located at specific sites in the ANS. Muscarinic receptors are located on effectors innervated by cholinergic nerves; this includes effectors at postganglionic parasympathetic junctions and a few postganglionic sympathetic junctions (most sweat glands and some blood vessels). Nicotinic receptors are found at different anatomic sites, including postganglionic nerve cell bodies at all autonomic ganglia, the adrenal medulla, and skeletal muscle. There are also different types of structurally related adrenergic receptors (α1, α2, β1, β2, β3)10,37 that are found at postganglionic sympathetic junctions where norepinephrine is released from postganglionic sympathetic nerves. These adrenergic receptors do not have a precise anatomic distribution, however; some effector organs have only a single adrenergic receptor, whereas other organs have two or more adrenergic receptor types. The fact that there are significant differences in autonomic receptor types is supported by the discovery of agonists that stimulate one receptor type but not others and of antagonists that block one receptor but not others. Research has revealed the existence of additional subtypes for adrenergic and cholinergic receptors, and it is anticipated that drugs highly selective for these additional receptor subtypes will be developed for future clinical use.

Mechanism of Neurotransmitter Release

The current understanding of exocytotic neurotransmitter release has arisen from the work of many different investigators. Although several mechanisms for neurotransmitter release may exist, as summarized in reviews on the subject,26,36 one main model has been developed for the secretion of classic neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine (Figure 5-4) and norepinephrine (Figure 5-5). It has been proposed that when an action potential reaches the axon terminal it depolarizes the membrane, leading to the opening of voltage-gated Ca++ channels.31 This activation of Ca++ channels causes high, but transient, increases in intracellular Ca++ concentrations near the neurotransmitter storage vesicles. Intracellular Ca++ activates calmodulin, a small Ca++-binding protein found in nearly all cells.14 Calmodulin activates an enzyme called Ca++/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. This enzyme, found in extremely high concentrations in neurons (approximately 1% of total protein), catalyzes the phosphorylation of several proteins associated with the storage vesicle, including synapsin I. Synapsin I binds to actin present on the cytoskeleton and is thought to interact with other proteins (e.g., synaptobrevin, synaptophysin, and synaptoporin) to initiate docking and fusion of the storage vesicle with the cell membrane, followed by exocytotic neurotransmitter release. The neurotransmitter crosses the synaptic or junctional cleft and binds to its receptor on the nerve or effector cell membrane, which could be located on a ganglionic neuron, a skeletal muscle fiber, an autonomic effector, or a cell in the CNS.

ADRENERGIC NEUROTRANSMISSION

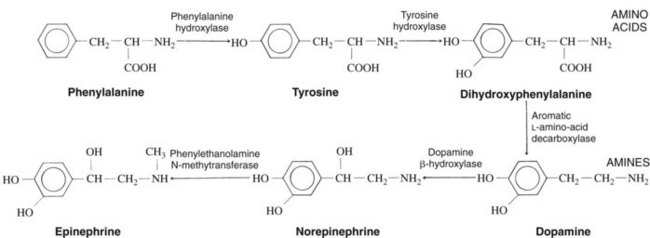

Catecholamine Synthesis

The catecholamines norepinephrine and epinephrine are the primary neurotransmitters and hormones released after stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. The synthesis and storage of the catecholamines can be modified by a number of clinically useful drugs. The synthetic process, shown in Figure 5-6, involves numerous enzymes that are synthesized in the nerve cell body and carried by axoplasmic transport to the nerve endings. The enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which catalyzes the conversion of tyrosine to dihydroxyphenylalanine, is the rate-limiting enzyme in this process; any drug that inhibits the function of tyrosine hydroxylase reduces the rate at which norepinephrine is produced in the nerve terminal. The concentration of norepinephrine in the cytoplasm is one of the factors that regulates its own formation, principally by feedback inhibition on tyrosine hydroxylase activity.27 The enzyme phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase, which catalyzes the conversion of norepinephrine to epinephrine, occurs almost exclusively in the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and is missing in peripheral nerve terminals.3 Norepinephrine is the final product in most adrenergic nerves, whereas mainly epinephrine (80%), with some norepinephrine (20%), is produced in adrenal chromaffin cells in human beings.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses