CHAPTER 47 Analgesic Use for Effective Pain Control*

Fear of pain is a significant reason why many people avoid seeking dental care. No matter how successful or how effectively performed, most dental surgical procedures produce tissue trauma and release potent mediators of inflammation and pain. In the past, postoperative pain was thought to be inevitable and harmless. We now know that unrelieved pain after surgery or trauma has negative physical and psychological consequences. Acute pain is often associated with a reactive anxiety and an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity, resulting in tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, mydriasis, and pallor. A patient with severe tooth or jaw pain may avoid eating or drinking and may become malnourished and dehydrated. Severe chest, abdominal, or back pain may lead to shallow breathing and cough suppression in an attempt to “splint” the injured site, followed by retained pulmonary secretions and pneumonia.19,37 Unrelieved pain may also delay the return of normal gastric and bowel function in a postoperative patient.41 If managed aggressively, pain is preventable or controllable in most cases.

Undertreatment of pain is a significant medical problem. Numerous clinical surveys have shown that postoperative pain is often inadequately treated because of undermedication, leaving patients to suffer needlessly.14,31 Recognition of the widespread inadequacy of pain management and the detrimental effects of untreated pain has led to corrective efforts in numerous health care disciplines involved with pain management. These efforts culminated in 1992, when the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, a division of the U.S. Public Health Service, published its Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma.2 This guideline represents the efforts of a multidisciplinary panel of expert clinicians and researchers. It provides an excellent framework for the care of patients with acute pain and includes a section on pain control specifically for dental surgery.

PAIN CLASSIFICATION

Neuropathic pain is thought to be a result of aberrant somatosensory activity either in the peripheral nervous system or the central nervous system (CNS) (see Chapter 23). It is frequently characterized by paroxysmal shooting or electrical shock–like pains, often on a background of burning or constricting sensation. Examples of neuropathic pain encountered in the orofacial region include trigeminal neuralgia, burning mouth syndrome, and postherpetic neuralgia. Orofacial pain of neuropathic origin generally requires more sophisticated diagnostic testing and management; this sort of care is frequently available at specialized clinical practices.

PAIN ASSESSMENT

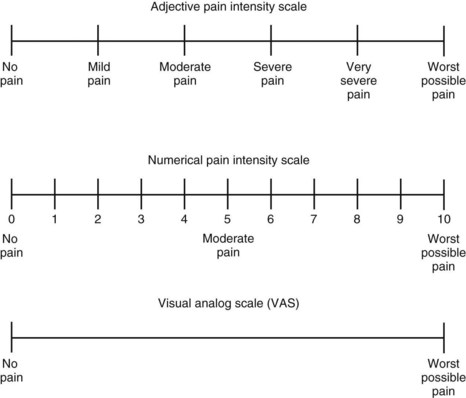

Successful assessment and control of pain depend partly on establishing effective communication between the dentist and the patient. Patients should be informed that pain relief is an important part of their health care. Because pain is a subjective phenomenon, the care provider must accept that the patient’s self-report is the most accurate and reliable indicator of the existence and intensity of pain and any resultant distress.2 This orientation is reflected in a commonly cited definition of pain: Pain is whatever the person experiencing it says it is and exists whenever he or she says it does.27 Self-report measurement tools such as adjective or numerical rating scales or visual analogue scales can assist the patient in quantifying and characterizing the pain (Figure 47-1).

Assessment of the patient’s pain is a crucial part of the initial evaluation to estimate analgesic requirements. To determine the adequacy of the chosen analgesic regimen, the clinician must also assess pain intensity and pain relief at the peak of the analgesic effect and at regular intervals after the initiation of analgesic treatment.9

MISCONCEPTIONS REGARDING PAIN AND ANALGESICS

CHOICE OF ANALGESIC REGIMEN

Pharmacologic control of pain can be directed at any of three nociceptive processes: (1) initiation of impulses, (2) propagation of the impulses, and (3) perception of painful stimuli. NSAIDs are thought to act primarily at the site of initiation of nociceptive impulses. Although separating their anti-inflammatory effects from their analgesic effects is difficult, nonopioid drugs, such as salicylates, other NSAIDs, and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, work predominantly in the periphery by preventing the synthesis and release of inflammatory mediators that sensitize nociceptive receptors to other algesic mediators, such as bradykinin, and to physical forces. More recent studies suggest that NSAIDs may also have central effects.6,24 Acetaminophen has been shown to have analgesic and antipyretic properties, but it lacks significant anti-inflammatory effects. Acetaminophen seems to exert its effects in the CNS and in the periphery.1,28,39

Opioids decrease the perception of pain in the CNS. Opioid analgesics act in the CNS at receptors in the spinal cord, rostroventral medulla, and periaqueductal gray matter. These anatomic loci are considered important to the perception of pain (see Chapter 20). Laboratory studies have also identified and characterized opioid receptors in peripheral tissue. This finding has led to clinical studies that have identified opioids as contributors to antinociceptive responses in the peripheral nervous system.22,29 Likewise, there has been a search for drugs that reduce the incidence of opioid peripheral side effects, most notably constipation, in patients taking these drugs for various types of pain.4

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses