Chapter 4

Initial Assessment and Treatment Planning

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to describe the principles of assessment and treatment planning for patients undergoing conscious sedation.

Outcome

After reading this chapter you should have an understanding of the importance of pre-sedation assessment and the factors that influence treatment planning for patients undergoing conscious sedation.

Introduction

The assessment of the anxious dental patient is probably one of the most important and challenging aspects of everyday clinical practice. Unless a reasonable rapport is achieved at this stage and the patient perceives that the dental team is “on their side”, there is a risk that subsequent treatment may fail, no matter how hard one tries, or which conscious sedation technique is used. Many patients expect dental treatment to be uncomfortable and even painful. These concerns may cause reactions which range from mild apprehension, through various degrees of anxiety to irrational fear (phobia). Both pain and anxiety should be adequately controlled to minimise the risk of adverse physiological effects resulting from these psychological responses. The risk of an adverse event is increased in individuals with medical conditions and in elderly patients.

Any social or medical problem represents a departure from normal and may require modifications in treatment planning. This may involve simply a change in attitude on the part of the practitioner or a more significant alteration in the scheduling of dental care. In all events, it is important to match the patient’s ability to cope with treatment and the pace of delivery. In particular, vulnerable patients require positive management rather than being denied good quality care. For example, people with learning disabilities will require more information and more time, often involving other professionals and family or carers.

The principal role of conscious sedation is to allay apprehension, anxiety or fear. It is also used to reduce the stress associated with traumatic or prolonged procedures (e.g. implant surgery) and/or to control gagging. Additionally, conscious sedation is beneficial in stabilising the blood pressure in patients with hypertension or a history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease. To be able to recognise individuals who would benefit from conscious sedation, the dental team must be sensitive to the typical signs and symptoms of anxiety.

Signs of anxiety:

-

clenched fists

-

sweaty hands

-

pallor

-

distracted appearance

-

sitting forward in the dental chair

-

holding handbag/tissue tightly

-

persistent talking and interruption or silent demeanour

-

frequent throat clearing

-

constant looking around

-

not smiling

-

resdessness and fidgeting

-

licking lips

-

aggressive behaviour.

Symptoms of anxiety:

-

dry mouth

-

need to visit lavatory

-

nausea (and vomiting)

-

fainting

-

tiredness

-

sweating.

The Assessment Visit

A satisfactory first visit is crucial to the success of subsequent treatment under sedation. This meeting should ideally not be in the surgery environment and should be in the nature of an informal “chat”. Many patients feel unable to attend on their own. A supportive accompanying relative or friend may make the assessment easier for both the patient and the dentist. However, not all accompanying persons are helpful and some may actually hinder the process. Beware the husband or wife who does not allow their spouse to answer your questions without interruption! It is often easy to spot the relative who will best help the patient by remaining in the waiting room during the assessment interview. Young children are a special case and should never be assessed without a parent or carer present.

There is a great deal of information to be acquired from the patient and so it is important to have a structured approach. Since patients often become more relaxed as the interview proceeds, it is advisable to defer any questions which may be perceived as threatening until the patient is more relaxed. It should never be forgotten that the patient is also assessing the operator during this interview.

The following areas need to be explored during the initial assessment.

What is the Problem?

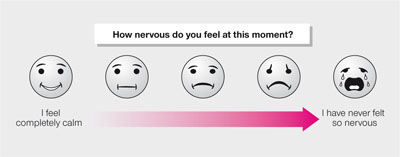

It is often helpful to get the patient to complete a questionnaire about the nature of their fears. Suitable questionnaires for adults include the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (Fig 4-1) and for children the Venham Scale (Fig 4-2). These serve to break the ice and allow other lines of questioning to be introduced. It is not helpful to encourage the patient to relive and recall a series of unsatisfactory dental experiences. Remember, for some patients discussing dentistry can be frightening! Rather, the dentist should steer the conversation towards positive solutions whilst reassuring the individual that their concerns are being taken seriously. It is unwise, however, to be drawn into promising too much too soon, in relation to the benefits of sedation, or the extent of dental treatment that may be provided. Many anxious patients have unrealistic expectations. Unless this is resolved at an early stage, it is likely that patients will be dissatisfied if treatment does not progress as they would have liked.

Fig 4-1 Modified Dental Anxiety Scale.

Fig 4-2 Venham Scale of Anxiety.

Medical History and Investigations

It is essential that a comprehensive medical history is obtained by the dentist. This takes time to record properly and should not be rushed or delegated to an/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses