Significance of Clinical and Biologic Information

In one study of the topic of periodontal tissue regeneration, investigators reported that a treatment that resulted in a gain of 1.2 mm in clinical attachment level and a reduction of 1 mm in probing pocket depth “may not have a great clinical impact.”4 In another study of a local antimicrobial, the investigators reported that a treatment that resulted in a gain of 0.0 mm in clinical attachment level and a reduction of 0.2 mm in probing depth had such clinical significance that it should “be used universally.”28 This example illustrates that different individuals will reach different decisions regarding what is meant by the term clinical significance. As a result, the term clinically significant has become more useful to marketers than to clinicians.

Tangible versus Intangible Benefits

Tangible benefits are those treatment outcomes that reflect how a patient feels, functions, or survives. The word tangible is defined as “capable of being precisely identified or realized by the mind.” Examples of tangible benefits could include improved oral health–related quality of life,14,15 a decrease in self-reported symptoms (e.g., bleeding) after brushing, the prevention of tooth loss, or the elimination of a painful periodontal abscess. These examples of treatment benefits can be precisely identified or realized by the patient’s mind; in other words, they are tangible. Tangible benefits can also be referred to as “clinically relevant” benefits or “clinically meaningful” benefits.

A first step in assessing the clinical significance of a treatment is to determine whether the documented treatment benefits are tangible or intangible. This distinction is important, because intangible benefits often do not necessarily translate into tangible benefits. A medication that lowers elevated blood lipid levels (an intangible benefit) may also shorten the life span (a tangible patient harm).28 A treatment that increases bone density (an intangible benefit) can increase fracture risk (a tangible patient harm).11 A treatment that provides extensive periodontal bone regeneration (an intangible benefit) can lead to tooth loss (a tangible harm).13

A treatment that has been shown to provide tangible benefits has a higher level of clinical significance than a treatment for which only evidence of intangible benefits exists. The finding that implant-supported dentures improve quality of life1 has a higher level of clinical significance than the finding that scaling increases probing attachment levels. The finding that an endodontic treatment reliably eliminates tooth pain has a higher level of clinical significance than the finding that chlorhexidine reduces Streptococcus mutans levels.

Size of the Treatment Effect

At another extreme, if the likelihood of obtaining an expected treatment benefit is small, substantial rigor in both the design and analysis of controlled clinical trials is required. The benefit of mammography screening for the early detection of breast cancer,9 the benefit of one “clot-buster” drug over another after a myocardial event, and the benefit of local antibiotics for the treatment of periodontitis are all so small that large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are required to provide reliable evidence of whether small benefits are indeed associated with treatment.

The likelihood of obtaining a treatment benefit is a determinant of clinical significance; the larger the likelihood, the more confident a patient can feel that a treatment will be successful. Although it is possible to have a clear, unequivocal definition of what constitutes a tangible benefit associated with treatment, it is not possible to have a similar rigorous definition of what can be considered a large likelihood. We define a “large treatment effect” as an NNT of 5, which, under fortuitous circumstances, can be reliably identified with nonexperimental study designs.5,26

Defining Four Levels of Clinical Significance

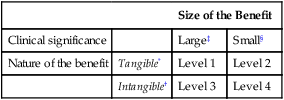

On the basis of the nature of the benefit (i.e., tangible/intangible) and the size of the treatment effect (i.e., large/small), four levels of clinical significance can be defined (Table 30-1). These are numbered from 1 to 4 in order of decreasing levels of significance.

TABLE 30-1

Definition of Levels of Significance Based on the Size and Nature of the Benefit

| Size of the Benefit | |||

| Clinical significance | Large‡ | Small§ | |

| Nature of the benefit | Tangible* | Level 1 | Level 2 |

| Intangible† | Level 3 | Level 4 | |

*Tangible benefits are outcomes that directly measure how a patient feels, functions, or survives.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses