3 The Primary (Deciduous) Teeth

Life Cycle

After the roots of the primary dentition are completed at about age 3, several of the primary teeth are in use only for a relatively short period. Some of the primary teeth are found to be missing at age 4, and by age 6, as many as 19% may be missing.1 By age 10, only about 26% may be present. The second molars in both arches and the maxillary incisors appear to be the most unstable of the primary teeth. Even so, the developing and completed primary dentition serves a number of purposes during that time and the period of transition to the permanent dentition.

Importance of Primary Teeth

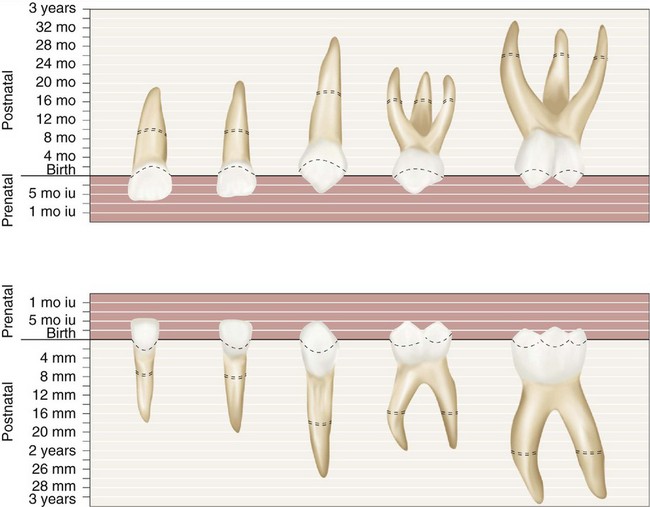

The general order of eruption of the primary dentition is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 3-1: central incisor, lateral incisor, first molar, canine, and second molar, with the mandibular pairs preceding the maxillary teeth.2,3 The loss of the deciduous teeth tends to mirror the eruption sequence: incisors, first molars, canines, and second molars, with the mandibular pairs preceding the maxillary teeth.

A lack of space associated with premature loss of deciduous teeth is a significant factor in the development of malocclusion and is considered in Chapter 16. The development of adequate spacing (Figure 3-2) is an important factor in the development of normal occlusal relations in the permanent dentition. Thus there should be no question of the importance of preventing and treating dental decay and providing the child with a comfortable functional occlusion of the deciduous teeth. Therefore in this book the primary teeth are described in advance of the permanent dentition so that they may be given their proper sequence in the study of dental anatomy and physiology. The development of the primary occlusion is considered in Chapter 16.

Nomenclature

Some of the terminology for the primary dentition has already been introduced in Chapter 2; therefore the coverage here is more in the nature of a review. The process of exfoliation of the primary teeth takes place between the seventh and the twelfth years. This does not, however, indicate the period at which the root resorption of the deciduous tooth begins. It is only 1 or 2 years after the root is completely formed and the apical foramen is established that resorption begins at the apical extremity and continues in the direction of the crown until resorption of the entire root has taken place and the crown is lost from lack of support.

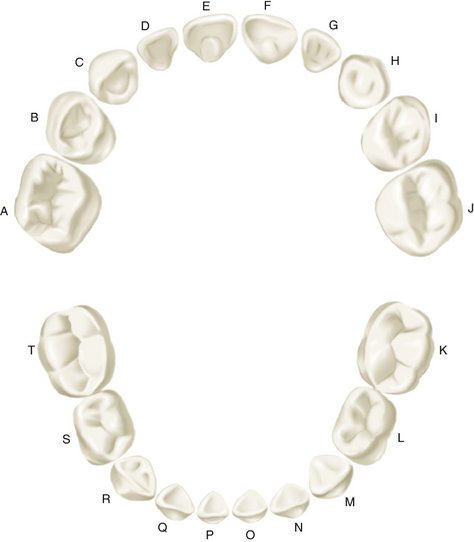

The primary teeth number 20 total—10 in each jaw—and they are classified as follows: four incisors, two canines, and four molars in each jaw. Figure 3-3 shows the primary dentition as numbered with the universal system of notation described in Chapter 1. Beginning with the median line, the teeth are named in each jaw on each side of the mouth as follows: central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, first molar, and second molar.

Figure 3-3 Universal numbering system for primary dentition.

(From Ash MM, Ramfjord S: Occlusion, ed 4, Philadelphia, 1995, Saunders.)

The first permanent molar, commonly called the 6-year molar, makes its appearance in the mouth before any of the primary teeth are lost. It comes in immediately distal to the primary second molar (see Figure 2-10).

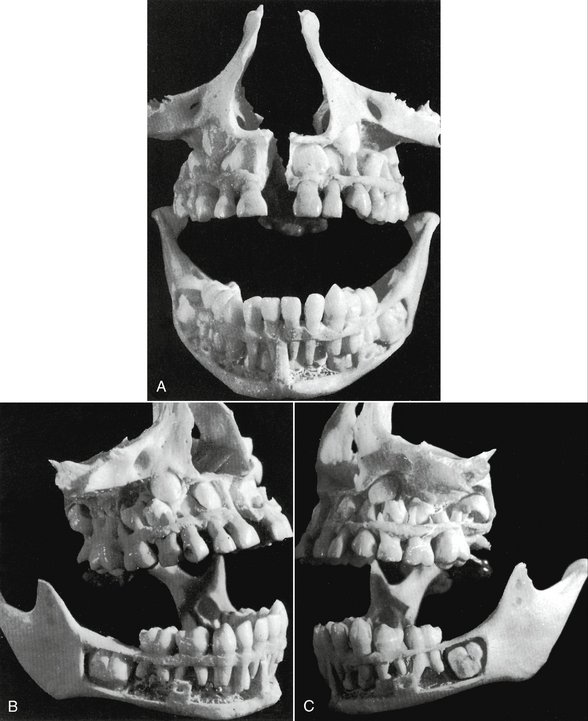

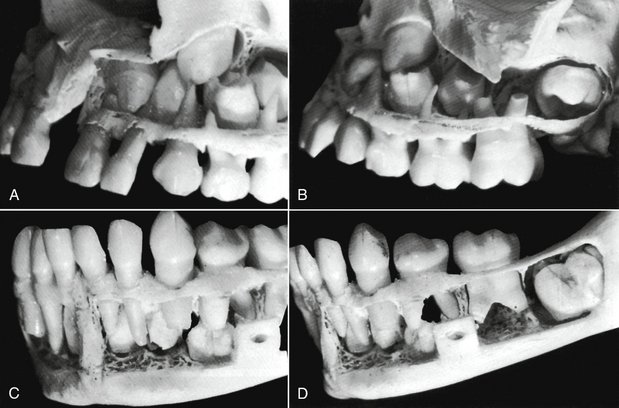

The primary dentition is complete at about 2.5 years of age, and no obvious intraoral changes in the dentition occur (Figures 3-4 and 3-5) until the eruption of the first permanent molar. The position of the incisors is usually relatively upright with spacing often between them. Attrition occurs, and a pattern of wear may be present.

Figure 3-5 A sectional close-up of the specimen in Figure 3-4. A, The left side of the maxilla. The developing crowns of the central and lateral incisors, the canine, and two premolars are clearly in view. B, The left side of the maxilla, posteriorly. The molar relationship, both deciduous and permanent, is accented here. C, This is a good view of the mandible anteriorly and to the left. Permanent central and lateral incisors and the canine may be seen. Notice that the permanent canine develops distally to the primary canine root. D, Posteriorly, examination of the specimen mandible fails to find crown development of permanent premolars. However, the hollow spaces showing between the roots of primary molars may indicate a loss of material during the difficult process of dissection. The first permanent molar has progressed in crown formation, but the maturation of the whole tooth with alignment is far behind its opposition in the maxilla above it (see Figure 3-4, C).

The primary molars are replaced by permanent premolars. No premolars are present in the primary set, and no teeth in the deciduous set resemble the permanent premolar. However, the crowns of the primary maxillary first molars resemble the crowns of the permanent premolars as much as they do any of the permanent molars. Nevertheless, they have three well-defined roots, as do maxillary first permanent molars. The deciduous mandibular first molar is unique in that it has a crown form unlike that of any permanent tooth (see Figure 3-24, C). It does, however, have two strong roots, one mesial and one distal—an arrangement similar to that of a mandibular permanent molar. These two primary teeth, the maxillary and mandibular first molars, differ from any teeth in the permanent set when crown forms are compared, in particular (see Figures 3-21 and 3-24). The primary first molars, maxillary and mandibular, are described in detail later in this chapter.

Major Contrasts between Primary and Permanent Teeth

In comparison with their counterparts in the permanent dentition, the primary teeth are smaller in overall size and crown dimensions. They have markedly more prominent cervical ridges, are narrower at their “necks,” are lighter in color, and have roots that are more widely flared; in addition, the buccolingual diameter of primary molar teeth is less than that of permanent teeth.4 More specifically, in comparison with permanent teeth, the following differences are noted:

Pulp Chambers and Pulp Canals

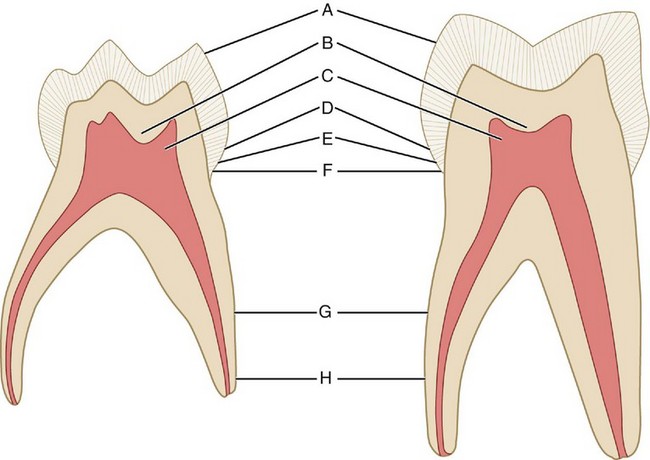

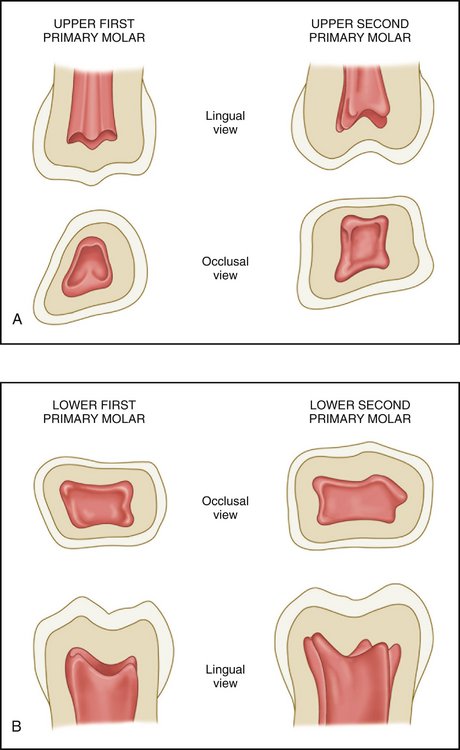

A comparison of sections of primary and permanent teeth demonstrates the shape and relative size of pulp chambers and canals (Figure 3-6), which is noted here:

Figure 3-7 A and B, Pulp chambers in the primary molars. Note the contours of the pulp horns within them.

(Modified from Finn SB: Clinical pedodontics, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1957, Saunders.)

Studying the comparisons between the deciduous and the permanent dentitions (Figures 3-8 and 3-9) is of utmost importance. Discussion of further variations between the macroscopic form of the deciduous and the permanent teeth follows, with a detailed description of each deciduous tooth.

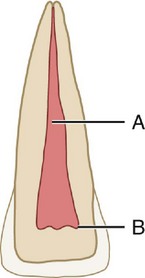

Figure 3-8 Permanent central incisor. A, Pulp canal; B, pulp horns. This figure represents a sectioned central incisor of a young person. Although the pulp canal is rather large, it is smaller than the pulp canal shown in Figure 3-9, and it becomes more constricted apically. Note the dentin space between the pulp horns and the incisal edge of the crown.

Figure 3-9 Primary central incisor. A, Pulp canal; B, pulp horns. This figure represents a sectioned primary central incisor. The pulp chamber with its horns and the pulp canal are broader than those found in Figure 3-8. The apical portion of the canal is much less constricted than that of the permanent tooth. Note the narrow dentin space incisally.

Detailed Description of Each Primary Tooth

MAXILLARY CENTRAL INCISOR

Labial Aspect

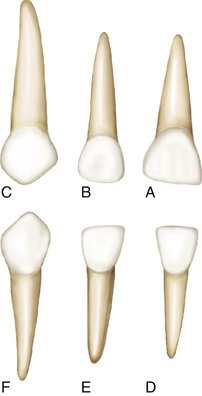

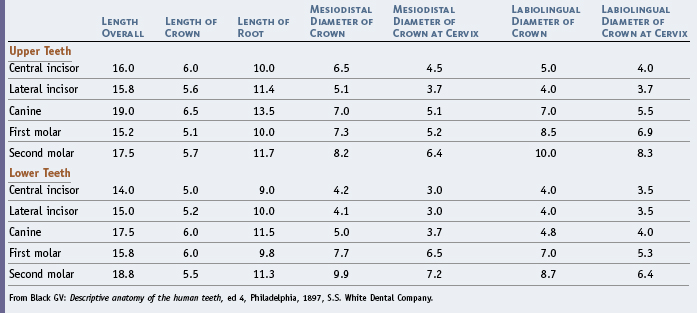

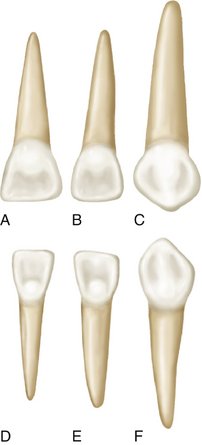

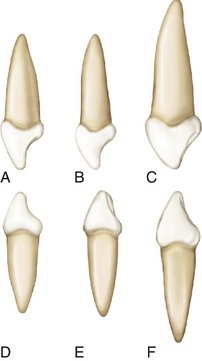

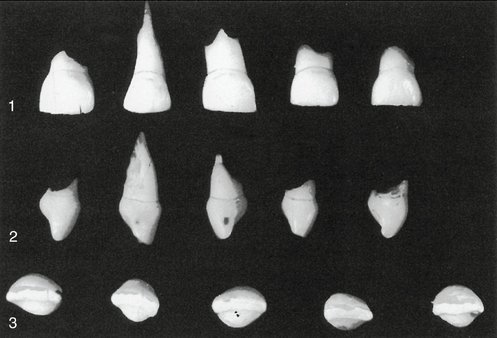

In the crown of the primary central incisor, the mesiodistal diameter is greater than the cervicoincisal length (Figures 3-10 and 3-11, A). (The opposite is true of permanent central incisors.) The labial surface is very smooth, and the incisal edge is nearly straight. Developmental lines are usually not seen. The root is cone-shaped with even, tapered sides. The root length is greater in comparison with the crown length than that of the permanent central incisor. It is advisable when studying both the primary and permanent teeth to make direct comparisons between the table of measurements of the primary teeth (Table 3-1) and that of permanent teeth (see Table 1-1).

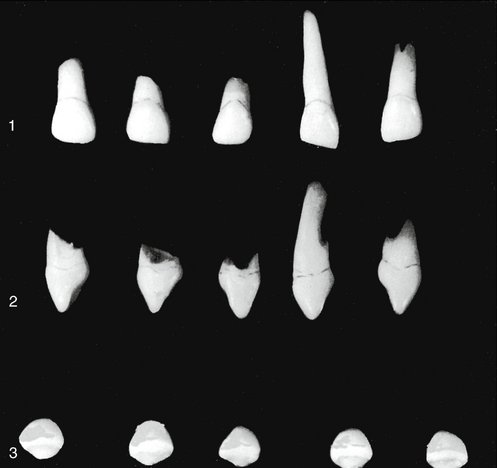

Figure 3-10 Primary maxillary central incisors (first incisors). 1, Labial aspect. Note the lack of character in the mold form; also note the mesiodistal width compared with the shorter crown length. A little of the crown length was lost through abrasion before the date of extraction. 2, Mesial aspect. The cervical ridges are quite prominent labially and lingually, with the bulge much greater than that found on permanent incisors. This characteristic is common to each primary tooth to a varied degree. Normally, these curvatures are covered by gingival tissue with epithelial attachment (see Chapter 5). 3, Incisal aspect.

Lingual Aspect

The lingual aspect of the crown shows well-developed marginal ridges and a highly developed cingulum (Figure 3-12, A). The cingulum extends up toward the incisal ridge far enough to make a partial division of the concavity on the lingual surface below the incisal edge, practically dividing it into a mesial and distal fossa.

Mesial and Distal Aspects

The mesial and distal aspects of the primary maxillary central incisors are similar (Figure 3-13, A; see also Figure 3-10). The measurement of the crown at the cervical third shows the crown from this aspect to be wide in relation to its total length. The average measurement is only about 1 mm less than the entire crown length cervicoincisally. Because of the short crown and its labiolingual measurement, the crown appears thick at the middle third and even down toward the incisal third. The curvature of the cervical line, which represents the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), is distinct, curving toward the incisal ridge. However, the curvature is not as great as that found on its permanent successor. The cervical curvature distally is less than the curvature mesially, a design that compares favorably with the permanent central incisor.

Incisal Aspect

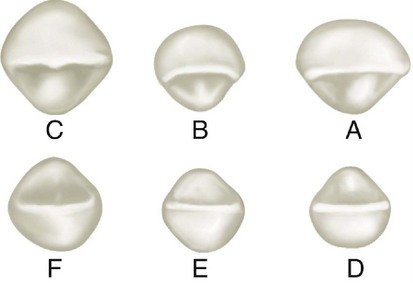

An important feature to note from the incisal aspect is the measurement mesiodistally compared with the measurement labiolingually (Figure 3-14, A; see also Figure 3-10, 3). The incisal edge is centered over the main bulk of the crown and is relatively straight. Looking down on the incisal edge, the labial surface is much broader and also smoother than the lingual surface. The lingual surface tapers toward the cingulum.

MAXILLARY LATERAL INCISOR

In general, the maxillary lateral is similar to the central incisor from all aspects, but its dimensions differ (Figure 3-15; see also Figures 3-11, B; 3-12, B; 3-13, B; and 3-14, B). Its crown is smaller in all directions. The cervicoincisal length of the lateral crown is greater than its mesiodistal width. The distoincisal angles of the crown are more rounded than those of the central incisor. Although the root has a similar shape, it is much longer in proportion to its crown than the central ratio indicates when a comparison is made.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses