Having established the patient’s diagnoses and problems, the dentist is prepared to begin developing a treatment plan. This process can be rather simple for patients with few problems and relatively good oral health. Treatment can commence quickly, especially when the patient is knowledgeable about dentistry, harbors little anxiety toward dental treatment, and has the necessary financial resources available. More commonly though, the patient has many diagnoses and problems, often interrelated and complex, that require analysis before treatment can begin. The dentist may wonder whether an individual problem can or should be addressed, and what treatment options are available. Would a crown, for instance, be better than a large direct restoration to restore a carious lesion? Would an implant be a more satisfactory option than a fixed partial denture to replace a missing tooth? Which treatment should be provided first, and which procedures can be postponed until later? What role should the patient have in any of these decisions? Is he or she even fully aware of the individual dental problems? How successful, overall, will the planned treatment be?

Although all dentists struggle with these questions, experienced practitioners know when to address each issue individually and when to step back and look at all aspects of the case as a whole. They are also aware that treatment planning cannot occur in a vacuum and must involve the patient. This means educating patients about their problems and making them partners in determining the general direction and the specific elements of a proposed treatment plan.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide the reader with the fundamental skills necessary to begin creating treatment plans for patients. This includes developing treatment objectives, separating treatment into phases, presenting treatment plans to patients, sequencing procedures, consulting with other practitioners, obtaining informed consent, and documenting the treatment plan. Much of the material is presented as guidelines, which must be modified by the circumstances of each patient. Few, if any, rules are ironclad when treatment planning, and like many other aspects of dentistry, clinical decisions improve with experience.

DEVELOPING TREATMENT OBJECTIVES

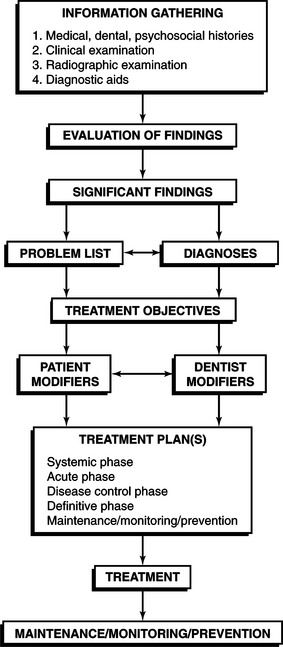

As we discussed in Chapter 1, the practitioner first determines what patient findings are significant and then creates a list of diagnoses and problems that formally document why treatment is necessary. After assessing the patient’s risk for ongoing and future disease (discussed in Chapter 2), the next step towards devising a treatment plan is to articulate, with the patient’s assistance, several treatment objectives (Figure 3-1). These objectives represent the intent, or rationale, for the final treatment plan. Treatment objectives are usually expressed as short statements and can incorporate several activities aimed at solving the patient’s problems. Good treatment objectives articulate clear goals, from both the dentist’s and the patient’s perspective. Objectives evolve from an understanding of the current diagnoses and problems and provide the link to actual treatment (Table 3-1).

Table 3-1

The Relationship Between Diagnoses, Problems, Treatment Objectives, and Treatment

Signs and Symptoms: Ms. Smith, a 45-year-old patient, requests an examination. She has been diagnosed with Sjögren’s syndrome. Her last visit to a dentist was 2 years ago for teeth cleaning. She reports symptoms of sore hands and wrist joints and a dry mouth. Her gingiva is red, and extensive plaque covers the necks of the teeth. Several teeth have small, dark areas on the facial enamel near the gingival margin, which are soft when evaluated with an explorer. The patient works in a convenience store and consumes an average of 1 liter of naturally sweetened carbonated beverage per day.

Patient Goals and Desires

Before creating any treatment plan, the dentist must first determine the patient’s own treatment desires and motivation to receive care. Patients usually have several expectations, or goals, that can be both short and long term in nature. The most common short-term goal is the resolution of the chief complaint or concern, for instance, relieving pain or repairing broken teeth. Long-term goals are usually more global and can be more difficult to identify, especially if the dentist only considers his or her own preconceived ideas of what the patient desires. For example, an understandable long-term goal would be maintaining oral health and keeping the teeth for a lifetime. Most dentists would extol this expectation, as would many patients, especially those who come to the dentist with good oral health. But for patients with a history of sporadic dental care, poor systemic health, or extensive (and potentially expensive) dental needs, individual goals can be quite different. A patient with terminal cancer may only wish to stay free of pain or to replace missing teeth to be able to eat more comfortably. On the other hand, a physically healthy patient with recurrent caries around many large restorations may be frustrated with past dental treatment and want any remaining teeth extracted and full dentures constructed.

Determining patient goals begins during the initial interview and can continue throughout the examination process. Careful probing of the patient’s past dental history provides an indication of past and future treatment goals. The practitioner should avoid asking leading questions about treatment expectations. Such questions may instead convey the dentist’s own personal goals, opinions, and biases and inhibit the patient from expressing his or her own goals and views. Some examples follow:

It is better to use open questions that elicit the patient’s thoughts and feelings and encourage the sharing of genuine concerns, especially regarding the chief complaint:

The dentist can influence a patient’s treatment goals. This often occurs when the patient has expectations that are difficult or even impossible to achieve, considering the condition of the mouth. For instance, the patient may want to retain his or her natural teeth, but is unaware of severe periodontal attachment loss. Ultimately the dentist needs to educate the patient about the dental problems and begin to suggest possible treatment outcomes.

Patient Modifiers

Treatment goals are frequently influenced by patient attributes, often referred to as patient modifiers. Positive modifiers include an interest in oral health, the ability to afford treatment, and a history of regular dental care. Commonly encountered negative modifiers include time and financial constraints, a fear of dental treatment, lack of motivation, poor oral health, destructive oral habits, and poor general health. Many patients are understandably concerned about the potential cost of care, especially when they know they have many dental problems. Whether the fees for services will function as a barrier to treatment depends on several variables, including the patient’s financial resources, the level of immediate care necessary, the types of procedures proposed (i.e., amalgams versus crowns or partial dentures), the feasibility of postponing care, and the availability of third-party assistance.

Poor motivation, a lack of good oral hygiene, or a diet high in refined carbohydrates can significantly affect the prognosis of any treatment plan. Nevertheless, occasionally such patients may still want treatment involving complex restorations, implants, and fixed or removable partial dentures. Before treatment is provided, the dentist must inform the patient of the high risk for failure and record this discussion in the patient record.

Dentist Goals and Desires

Dentists also aspire to certain goals when creating treatment plans for patients. Several are obvious, such as removing or arresting dental disease and eliminating pain. Other goals may be less apparent, especially to the patient, but are just as important nonetheless. Examples include providing the correct treatment for each problem, ensuring that the most severe problems are treated first, and choosing the best material for a particular restoration.

In gathering these altruistic goals together, the dentist would likely want to create an ideal treatment plan. Simply put, such a plan would provide the best, or most preferred, type of treatment for each of the patient’s problems. Thus, if a tooth has a large composite restoration that requires replacement, placing a crown might be considered the ideal treatment. If the patient has missing teeth, then the dentist might consider replacing them. The goal of ideal treatment planning provides a useful starting point for planning care. Unfortunately, such a plan may not take into account important patient modifiers or may fail to meet the patient’s own treatment objectives. In addition, one dentist’s ideal treatment plan can differ significantly from another’s, depending on personal preference, experience, and knowledge.

Creating a modified treatment plan balances the patient’s treatment objectives with those of the dentist’s. For instance, a patient with financial limitations may not be able to replace missing posterior teeth. The dentist needs to explain (and document) what may happen without ideal treatment (i.e., in some instances, tipping and extrusion of the remaining teeth). Another example is the patient with several periodontally involved teeth that should be removed even though they are not excessively mobile or symptomatic at the present time. An appropriate treatment objective might be for the dentist to observe the teeth for the present, but be prepared to extract them if mobility increases or if the patient reports symptoms.

Incorporating the patient’s wishes into a treatment plan can be difficult to implement at times. A classic example is the patient with rampant dental caries involving both the anterior and posterior teeth. For esthetic reasons, the patient may be interested in restoring the anterior teeth first, but the dentist, after interpreting the radiographs, may detect more serious problems with the posterior teeth, such as caries nearing the pulp, and wish to treat these teeth first. Another example is the patient with poor oral hygiene and severe periodontal disease who wishes extensive fixed prosthodontic treatment begun immediately.

Dentist Modifiers

Every dentist brings factors to the treatment planning task that can influence goals for patient care and ultimately the sort of treatment plans that he or she creates. The astute dentist is aware of these modifiers, especially when they limit his or her ability to devise the most appropriate treatment plan to satisfy the patient’s dental needs and personal desires.

Knowledge

The dentist’s level of knowledge and experience can influence the selection of goals and objectives for patient care. At one extreme is the beginning dental student, with a limited knowledge base and little experience in treating patients. Such early practitioners may not recognize the patient’s treatment desires and modifying factors. As a result, they may create only ideal treatment plans, ignoring more appropriate solutions. At the other extreme is the complacent dentist who has been in practice for many years and has substantial clinical experience, but a knowledge base that has changed little since graduation. Such dentists may lack knowledge of new treatment modalities that could be offered to patients, preferring instead to limit what they do. For these clinicians the adage, “If all you have is a hammer, then everything is a nail,” unfortunately may be true. The conscientious practitioner is a lifelong student who is never complacent and who learns not only from his or her own experiences, but also from those of others. This dentist keeps up with current developments in the profession by attending continuing education courses, interacting with peers, and critically reading the professional literature.

Technical Skills

In addition to a sound knowledge base, the dentist must also have the technical ability to provide treatment. Many dentists choose not to provide certain procedures, such as implant placement, extraction of impacted third molars, or endodontic treatment for multirooted teeth. This is not necessarily a limiting factor per se when treatment planning, but it can be if the dentist does not consider referring the patient to another dentist who has the expertise to provide the treatment.

Treatment Planning Philosophy

Finally, each dentist develops an individual treatment planning philosophy that continues to evolve over years of treating patients. The dentist’s philosophy regarding treatment planning may vary considerably because of differences in his or her knowledge base, technical skills, clinical experience, and judgment. Treatment planning in a dental school environment is often different from treatment planning in a private practice. Students are often frustrated when instructors differ in treatment philosophies because of different educational backgrounds. Dental schools and dental practices may also control or recommend which treatment options practitioners can provide to patients. The recent graduate, starting out in practice, is often motivated to incorporate new techniques and materials different from those used in dental school. Dentists who have been in practice several years also try to keep up with new developments in the profession, which in theory can influence how they develop treatment plans for patients. For the most part, patients benefit from new materials and techniques. But patient care suffers when experienced or inexperienced practitioners adopt treatment philosophies that are unproven or empirical in nature. A good example is the unwarranted removal of sound amalgam restorations and replacement with gold or composite resin under the premise that the amalgam affects the patient’s systemic health. Such treatment can be unethical and may be a disservice to the patient by exposing teeth to the risk of pulpal damage or removal of additional tooth structure.

ESTABLISHING THE NATURE AND SCOPE OF THE TREATMENT PLAN

With the examination finished and the dentist confident that he or she has gained an awareness of the patient’s treatment desires, it is time to develop the treatment plan. The dentist has the responsibility to determine what treatment is possible, realistic, and practical for the patient. In many instances, this is a relatively straightforward process, especially for those patients with few problems and the resources and interest in preserving oral health. At the other end of the spectrum, the process is more complex for patients with many interrelated oral problems and a high degree of unpredictability regarding the final treatment outcome. For such cases, the dentist has at his or her disposal several useful techniques for developing treatment plans: visioning, identifying key teeth, and phasing procedures.

Visioning

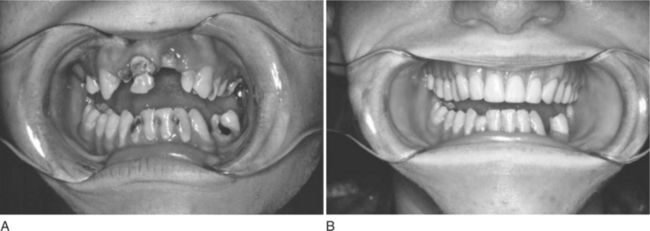

Dentists naturally contemplate treatment options while examining patients. The experienced practitioner will also develop a vision of what the patient’s mouth will look like when treatment is completed. The concept of having a vision of the final result could be described as analogous to deciding on the destination before starting a journey. Imagining one or more end points for the completed case is beneficial when evaluating different treatment approaches. For the patient with many severely decayed teeth in both arches, the dentist might see the patient ultimately wearing complete dentures or, alternatively, consider retaining some teeth and placing a removable partial denture, or even restoring more teeth and using implants to support fixed prostheses (Figure 3-2, A and B).

Figure 3-2 Visioning skills are useful when trying to arrive at treatment options for a patient with many problems. A, This 20-year-old woman had extensive dental caries, nonrestorable teeth, and limited financial resources. B, Of the several options presented, the patient chose to have the maxillary teeth removed and mandibular teeth restored.

Further exploration of each option requires the dentist to identify what steps are necessary to reach the treatment goals. Experienced dentists commonly use this technique of “deconstructive” thinking to explore each option. In the first example, the dentures can only be made after the remaining teeth have been extracted. Will all the teeth be extracted at the same time? The patient will need time to heal and might be without teeth for several weeks. On the other hand, possibly only the posterior teeth should be removed first and the anterior teeth retained to maintain a good appearance. After healing, dentures could be constructed for immediate placement after the remaining anterior teeth have been extracted. Thinking ahead again, the dentist considers the fact that immediate dentures often require relining 6 to 12 months after placement. Is the patient prepared to accept the additional cost?

Considering the second option, the dentist might envision the patient with removable partial dentures and again begin the process of deconstructing the final result. Which teeth will serve as abutments for the removable partial denture? A surveyed crown may be necessary on some or all of the teeth to achieve adequate retention of the prosthesis. For the teeth needing such crowns, insufficient tooth structure may remain and a foundation restoration or post and core will have to be provided. Endodontic therapy must be performed first before a post and core can be placed. The dentist may determine that the periodontal condition of several abutment teeth is poor, calling for a new treatment plan designed around different abutment teeth. Can a suitable partial denture be made using these alternative abutment teeth?

Experienced dentists perform this mental dance of forward and backward thinking almost automatically, constructing and deconstructing various treatment plans. Such practitioners can simultaneously vision proposed changes in the treatment plan at three levels: the individual tooth, the arch, and the overall patient. Dental students and recent graduates who lack experience and visioning skills need to work harder at coming up with various options and testing their clinical validity. Even for straightforward cases, it may be advantageous to construct mounted study casts and make diagnostic waxings to help evaluate possible options. Having a network of experienced dentists with whom casts and radiographs can be shared and cases discussed can be helpful. The dentist who practices alone may need to join a study club or develop relationships with experienced general and specialist dentists.

Key Teeth

When developing a treatment plan for the patient with a variety of tooth-related problems, such as periodontal disease, caries, and failing large restorations, a first step may be to identify the important or key teeth that can be salvaged. Such teeth often serve as abutments for fixed and removable partial dentures, and their position in an arch may add stability to a dental prosthesis. Retaining key teeth often improves the prognosis for other teeth or the case as a whole. Conversely the loss of a key tooth can limit the number of treatment options available to the patient.

Key teeth can be characterized as having several qualities. If enough of these qualities are present, the teeth may be important enough to make an extra effort to retain them.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses