Soft Tissue Calcifications and Ossifications

Laurie C. Carter

Disease Mechanisms

The deposition of calcium salts, primarily calcium phosphate, usually occurs in the skeleton. When it occurs in an unorganized fashion in soft tissue, it is referred to as heterotopic calcification. This soft tissue mineralization may develop in a wide variety of unrelated disorders and degenerative processes. Heterotopic calcifications may be divided into three categories, as follows:

Dystrophic calcification refers to calcification that forms in degenerating, diseased, and dead tissue despite normal serum calcium and phosphate levels. The soft tissue may be damaged by blunt trauma, inflammation, injections, the presence of parasites, soft tissue changes arising from disease, and many other causes. This calcification usually is localized to the site of injury. Idiopathic calcification (or calcinosis) results from deposition of calcium in normal tissue despite normal serum calcium and phosphate levels. Examples include chondrocalcinosis and phleboliths. Metastatic calcification results when minerals precipitate into normal tissue as a result of higher than normal serum levels of calcium (e.g., hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia of malignancy) or phosphate (e.g., chronic renal failure). Metastatic calcification usually occurs bilaterally and symmetrically.

When the mineral is deposited in soft tissue as organized, well-formed bone, the process is known as heterotopic ossification. The term heterotopic indicates that bone has formed in an abnormal (extraskeletal) location. The heterotopic bone may be all compact bone, or it may exhibit some trabeculae and fatty marrow. The deposits may range from 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter, and one or more may be present. Causes range from posttraumatic ossification, bone produced by tumors, and ossification caused by diseases such as progressive myositis ossificans and ankylosing spondylitis.

Clinical Features

Sites of heterotopic calcification or ossification may not cause significant signs or symptoms; they most often are detected as incidental findings during radiographic examination.

Imaging Features

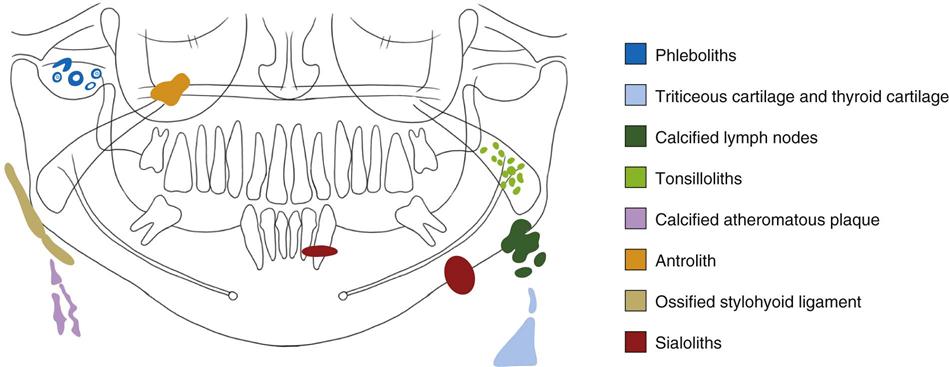

Soft tissue opacities are common, present on about 4% of panoramic radiographs (Fig. 28-1). In most cases, the goal is to identify the calcification correctly to determine whether treatment or further investigation is required. Some soft tissue calcifications require no intervention or long-term surveillance, whereas others may be life-threatening and the underlying cause requires treatment. When the soft tissue calcification is adjacent to bone, it sometimes is difficult to determine whether the calcification is within bone or soft tissue. Another radiographic view at right angles is useful. The important criteria to consider in arriving at the correct interpretation are the anatomic location, number, distribution, and shape of the calcifications. Analysis of the location requires knowledge of soft tissue anatomy, such as the position of lymph nodes, stylohyoid ligaments, blood vessels, laryngeal cartilages, and the major ducts of the salivary glands.

Heterotopic Calcifications

Heterotopic calcifications are calcifications that occur in an unorganized fashion in soft tissue.

Dystrophic Calcification

Disease Mechanism

Dystrophic calcification is the precipitation of calcium salts into primary sites of chronic inflammation or dead and dying tissue. This process is usually associated with a high local concentration of phosphatase, as in normal bone calcification; an increase in local alkalinity; and anoxic conditions within the inactive or devitalized tissue. A long-standing chronically inflamed cyst is a common location of dystrophic calcification.

Clinical Features

Common soft tissue sites include the gingiva, tongue, lymph nodes, and cheek. Dystrophic calcifications may produce no signs or symptoms, although occasionally enlargement and ulceration of overlying soft tissues may occur, and a solid mass of calcium salts sometimes can be palpated.

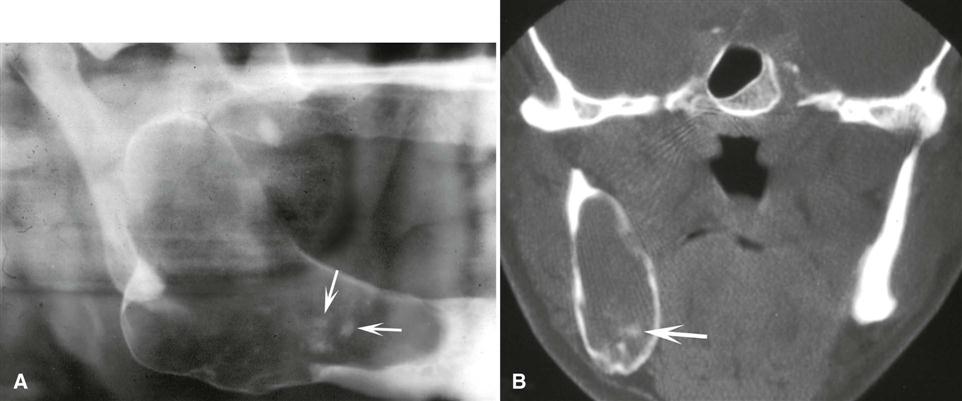

Imaging Features

The radiographic appearance of dystrophic calcification varies from barely perceptible, fine grains of radiopacities to larger, irregular radiopaque particles that rarely exceed 0.5 cm in diameter. One or more of these radiopacities may be seen, and the calcification may be homogeneous or may contain punctate areas. The outline of the calcified area usually is irregular or indistinct. Common sites are long-standing chronically inflamed cysts (Fig. 28-2) and polyps (Fig. 28-3).

Calcified Lymph Nodes

Disease Mechanism.

Dystrophic calcification occurs in lymph nodes that have been chronically inflamed because of various diseases, frequently granulomatous disorders. The lymphoid tissue becomes replaced by hydroxyapatite-like calcium salts, nearly effacing all nodal architecture. The presence of calcifications in lymph nodes implies disease, either active or the result of previously treated pathosis. In the past, tuberculosis was the most common disease causing calcified lymph nodes (scrofula or cervical tuberculous adenitis). Other well-known causes of lymph node calcification include bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination, sarcoidosis, cat-scratch disease, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis, lymphoma previously treated with radiation therapy, fungal infections, and malignancy (treated Hodgkin’s lymphoma and metastases from distant calcifying neoplasms, most notably metastatic thyroid carcinoma).

Clinical Features.

Calcified lymph nodes are generally asymptomatic, and the nodes are first discovered as an incidental finding on a panoramic radiograph. The most commonly involved nodes are the submandibular and superficial and deep cervical nodes. Less commonly, the preauricular and submental nodes are involved. When these nodes can be palpated, they are hard, lumpy, round to oblong masses.

Imaging Features

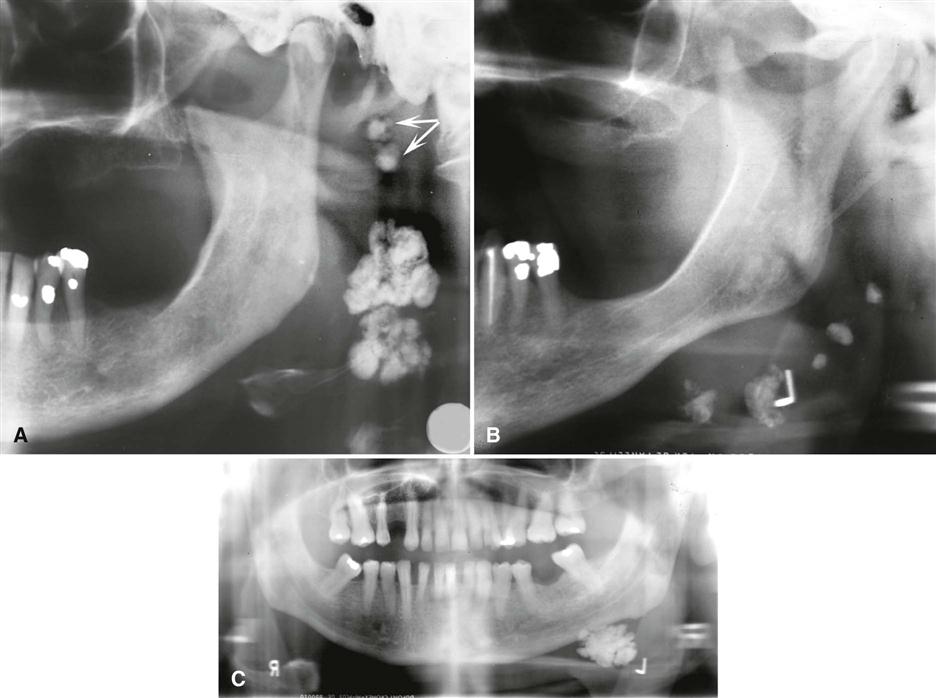

Location.

The most common location is the submandibular region, either at or below the inferior border of the mandible near the angle or between the posterior border of the ramus and cervical spine. The image of the calcified node sometimes overlaps the inferior aspect of the ramus. Lymph node calcifications may affect a single node or a linear series of nodes in a phenomenon known as lymph node “chaining” (Fig. 28-4).

Periphery.

The periphery is well defined and usually irregular, occasionally having a lobulated appearance similar to the outer shape of cauliflower. This irregularity of shape is of great significance in distinguishing node calcifications from other potential soft tissue calcifications in the area.

Internal Structure.

The internal aspect is without pattern but may vary in the degree of radiopacity, giving the impression of a collection of spherical or irregular masses. Occasionally, the lesion has a laminated appearance, or the radiopacity may appear only on the surface of the node (eggshell calcification). The pattern of nodal calcification does not reliably distinguish between benign and malignant disease.

Differential Diagnosis.

Differentiation between a single calcified lymph node and a sialolith in the hilar region of the submandibular gland may be difficult because both may appear near or adjacent to the inferior cortex of the mandible just anterior to the angle. Usually a sialolith has a smooth outline, whereas a calcified lymph node is usually irregular and sometimes lobulated. The differentiation can be made if the patient has symptoms related to the submandibular salivary gland (see Chapter 29). Occasionally, sialography may be necessary to make the differentiation. Another calcification that may have a similar appearance in this region is a phlebolith; however, phleboliths are usually smaller and multiple, with concentric radiopaque and radiolucent rings, and their shape may mimic a portion of a blood vessel.

Management.

Calcified lymph nodes usually do not require treatment; however, the underlying cause should be established in case treatment is required, such as in the case of active disease.

Dystrophic Calcification in the Tonsils

Synonyms.

Synonyms for dystrophic calcification in the tonsils include tonsillar calculi, tonsil concretions, and tonsilloliths.

Disease Mechanism.

Tonsillar calculi are formed when repeated bouts of inflammation enlarge the tonsillar crypts. Incomplete resolution of organic debris (dead bacteria and pus, epithelial cells, and food) can serve as the nidus for dystrophic calcification.

Clinical Features.

Tonsilloliths usually manifest as hard, round, white or yellow objects projecting from the tonsillar crypts, usually of the palatine tonsil. Small calcifications usually produce no clinical signs or symptoms. However, pain, swelling, fetor oris, dysphagia, or a foreign body sensation on swallowing has been reported with larger calcifications. Giant tonsilloliths stretching lymphoid tissue and resulting in ulceration and extrusion are much less common. These calcifications have been reported to occur in individuals between 20 and 68 years old; they are found more often in older age groups.

Imaging Features

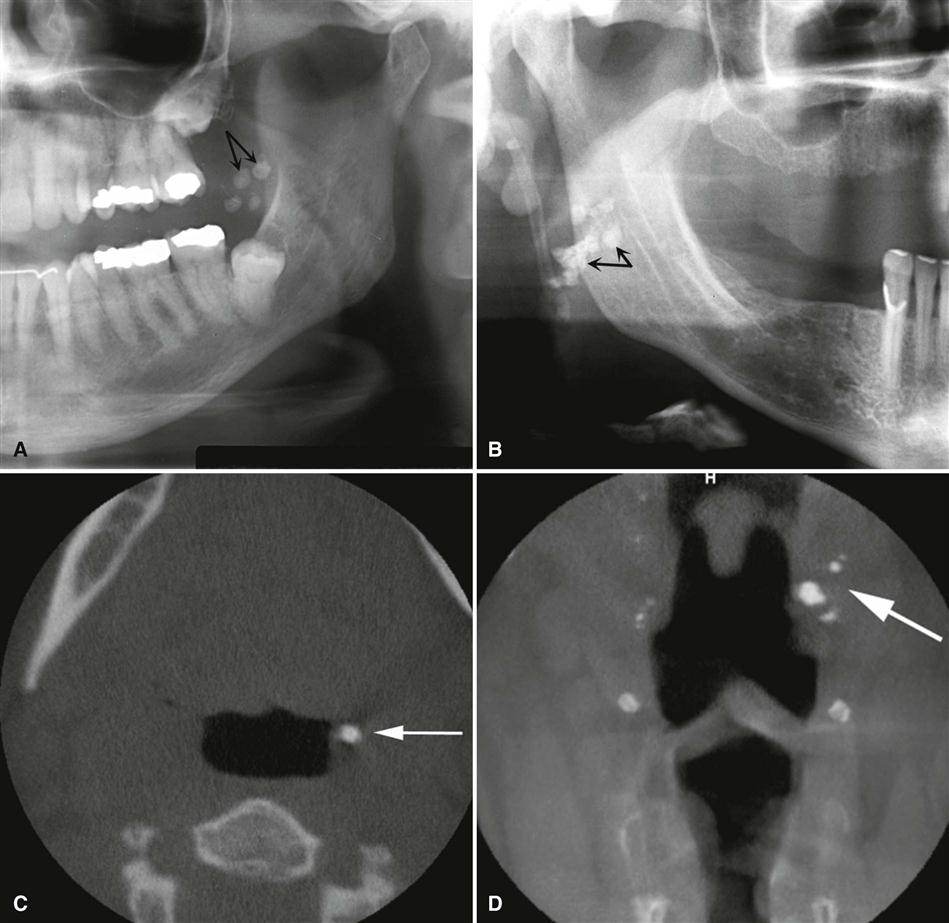

Location.

In a panoramic image, tonsilloliths appear as single or multiple radiopacities that overlap the midportion of the mandibular ramus in the region where the image of the dorsal surface of the tongue crosses the ramus in the oropharyngeal air spaces. Tonsilloliths frequently appear immediately inferior to the mandibular canal in the panoramic image (Fig. 28-5). On axial computed tomographic (CT) images, they appear in the soft tissue medial to the mandibular ramus and next to the lateral wall of the oropharyngeal air space.

Periphery.

The most common appearance of tonsilloliths is a cluster of multiple small, ill-defined radiopacities. Rarely, this calcification may attain a large size.

Internal Structure.

These calcifications appear slightly more radiopaque than cancellous bone and approximately the same as cortical bone.

Differential Diagnosis.

The clinical differential diagnosis includes calcified granulomatous disease, syphilis, mycosis, or lymphoma, which may produce a firm tonsillar mass. The essential radiographic differential diagnosis is a radiopaque lesion within the mandibular ramus, such as a dense bone island. When in doubt, a right-angle view such as a posteroanterior skull view or an open Towne’s view may show that the calcification lies to the medial aspect of the ramus. Three-dimensional imaging such as MDCT or cone-beam computed tomographic (CBCT) imaging may be necessary for precise localization.

Management.

No treatment is required for most tonsillar calcifications. In symptomatic patients, tonsilloliths may be expressed manually, possibly with the patient under sedation to suppress the gag reflex. Large calcifications with associated symptoms are removed surgically. Treatment of asymptomatic tonsilloliths may be considered in elderly patients with mechanical deglutition disorders and immunocompromised patients because of the risk for aspiration pneumonia.

Cysticercosis

Disease Mechanism.

When humans ingest eggs or gravid proglottids from the parasite Taenia solium (pork tapeworm), the covering of the eggs is digested in the stomach, and the larval form (Cysticercus cellulosae) of the parasite is hatched. The larvae penetrate the mucosa, enter the blood vessels and lymphatics, and are distributed as cysticerci in the tissues all over the body, but they preferentially locate to brain, muscle, skin, liver, lungs, subcutaneous tissues, and heart. They are also found in oral and perioral tissues, especially the muscles of mastication. The glycoprotein-rich cyst wall is greater than 100 µm thick and rarely elicits any host response when intact. In tissues other than the intestinal mucosa, the larvae eventually die years after infection and are treated as foreign bodies, eliciting a strong inflammatory reaction causing granuloma formation, scarring, and calcification. There is currently an increased incidence of cysticercosis in the American Southwest and urban Northeast, especially among Koreans and Hispanics. The problem is endemic in developing countries of Central and South America, Asia, and Africa, where there is fecal contamination of agricultural soil and pork is a valued food.

Clinical Features.

Mild cases of cysticercosis are completely asymptomatic. More severe cases have symptoms that range from mild to severe gastrointestinal upset with epigastric pain and severe nausea and vomiting. Invasion of the brain may result in seizures, headache, visual disturbances, acute obstructive hydrocephalus, irritability, loss of consciousness, and death. Examination of the oral mucosa may disclose palpable, well-circumscribed soft fluctuant swellings, which resemble a mucocele or benign mesenchymal neoplasm. Multiple small nodules may be felt in the region of the masseter and suprahyoid muscles and in the tongue, buccal mucosa, or lip.

Imaging Features.

While alive, larvae are not visible radiographically. Death of the parasites and development of calcifications in subcutaneous and muscular sites occurs years after the initial infection.

Location.

The oral locations of calcified cysticerci include the muscles of mastication and facial expression, the suprahyoid muscle, and the postcervical musculature as well as the tongue, buccal mucosa, and lip.

Periphery and Shape.

Multiple well-defined elliptic radiopacities that resemble grains of rice are viewed.

Internal Structure.

The internal aspect is homogeneous and radiopaque.

Differential Diagnosis.

Cysticercus may appear similar to a sialolith. However, the small size of the calcified nodules of cysticerci and their widespread dissemination, particularly in brain and muscles, are highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

Management.

Although basic sanitation (proper preparation of pork and avoiding fecal contamination of water supplies and vegetables) is needed to extinguish this source of infection, the symptoms that accompany the initial infestation are best treated by a physician using an anthelmintic such as albendazole or praziquantel. Adjunctive corticosteroids help stem the inflammatory reaction, and anticonvulsants may prevent epileptic seizures. After the larvae have settled and calcified in the oral tissues, they are harmless. However, it is important to carry out a detailed investigation in each patient to rule out the presence of the parasite in other locations and to perform serologic testing on close contacts to identify a possible source of infection.

Mönckeberg’s Medial Calcinosis (Arteriosclerosis)

Two distinct patterns of arterial calcification can be identified radiographically and histologically: Mönckeberg’s medial calcinosis and calcified atherosclerotic plaque.

Disease Mechanism.

The hallmark of arteriosclerosis is the fragmentation, degeneration, and eventual loss of elastic fibers followed by the deposition of calcium within the medial coat of the vessel.

Clinical Features.

Most patients are asymptomatic initially, although late in the course of the disease clinical pathosis such as cutaneous gangrene, peripheral vascular disease, and myositis as a result of vascular insufficiency may occur. Patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome also develop intracranial arterial calcifications.

Imaging Features

Location.

Medial calcinosis involving the facial artery or, less commonly, the carotid artery may be viewed on panoramic radiographs.

Periphery and Shape.

The calcific deposits in the wall of the artery outline an image of the artery. From the side, the calcified vessel appears as a parallel pair of thin, radiopaque lines (Fig. 28-6) that may have a straight course or a tortuous path and is described as a “pipe stem” or “tram-track” appearance. In cross section, involved vessels display a circular or ringlike pattern.

Internal Structure.

There is no internal structure because the diffuse, finely divided calcium deposits occur solely in the medial wall of the vessels.

Differential Diagnosis.

The radiographic appearance of arteriosclerosis is so distinctive as to be pathognomonic of the condition.

Management.

Evaluation of the patient for occlusive arterial disease and peripheral vascular disease may be appropriate. In addition, hyperparathyroidism may be considered because medial calcinosis frequently develops as a metastatic calcification in patients with this condition.

Calcified Atherosclerotic Plaque

Disease Mechanism.

Stenotic atheromatous plaque in the extracranial carotid vasculature is the major contributing source of cerebrovascular embolic and occlusive disease. Dystrophic calcification can occur in the evolution of plaque within the intima of the involved vessel.

Imaging Findings

Location.

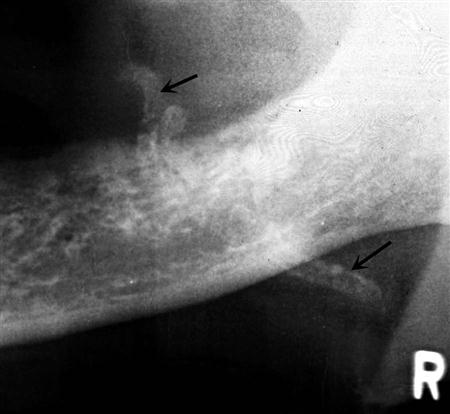

Atherosclerosis first develops at arterial bifurcations as a result of increased endothelial damage from shear forces at these sites. When calcification has occurred, these lesions may be visible in the panoramic radiograph in the soft tissues of the neck either superior or inferior to the greater cornu of the hyoid bone (where the common carotid artery splits into the external and internal carotid arteries) and adjacent to the cervical vertebrae C3, C4, or the intervertebral space between them (Fig. 28-7).

Periphery and Shape.

These soft tissue calcifications are usually multiple, irregular in shape, and sharply defined from the surrounding soft tissues, and they have a vertical linear distribution.

Internal Structure.

The internal aspect is composed of a heterogeneous radiopacity with radiolucent voids.

Differential Diagnosis.

Calcified triticeous cartilage may be mistaken for atherom/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses