Sleep-Disordered Breathing

A New and Evolving Role for the Dentist

Snoring and sleep apnea (apnea means cessation of breathing) are points along a spectrum that extends from benign or simple snoring with no sleep disturbance to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with excessive daytime sleepiness and the physiologic consequences of recurrent asphyxia.21 Over the years, there have been many dubious claims made regarding snoring cures. However, our knowledge has now greatly improved,13 and much can be done to manage OSA and its associated consequences. It is in the provision of oral devices for OSA that a key role for suitably trained dentists is developing.

Professor Colin Sullivan was the inventor of the mainstay therapy for sleep apnea: positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy. He was also an internationally renowned key opinion leader, and he advocated5 for dentists, as part of a multidisciplinary team, to play a critical role in four areas:

1. Treating adults with oral devices for snoring and mild to moderate OSA to slow the progression of the disease

2. Identifying patients at risk (both children and adults) by looking at their upper airways on a regular basis

3. Treating children with rapid maxillary expansion and avoiding deleterious orthodontic treatments

4. Recognizing the need for bimaxillary osteotomy among young adults with a need for maxillofacial correction

Dental Identification of Signs and Symptoms

Dental Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Possible Obstructed Breathing

Sleep Bruxism.

Although patients are commonly reported to experience both SDB and sleep bruxism, there is currently only a suspected association, because no evidence-based clinical trial has established a specific relationship. The bruxing patient’s repeated patterns of mandibular movement are primarily mediated by the central nervous system. It has been hypothesized that the advancement of the mandible opens the oropharynx, which could relieve some of the consequences of SDB.27,28

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

• Wear patterns on opposing incisors may suggest that the patient postures the mandible anteriorly to open the airway.42,43

• The mobility of the anterior teeth may be in excess of what might be estimated on the basis of the patient’s health and the support available from supporting periodontal structures.

• In the periodontitis-susceptible patient, progressive bone loss may be located or exaggerated in sites of unusual wear or mobility. The possible role of occlusal trauma in the amplification of the consequences of periodontitis is described in depth in the online version of Chapter 50 of this edition of this textbook.

• Tongue crenulations (scalloped borders) suggest that the patient is depressing the tongue forward against the mandibular teeth regularly to open their oral airway.

• The development of an anterior or lateral open-bite relationship of the opposing teeth may result from tongue posturing.

• Sleep bruxism may develop or increase.

• The dimpling of the cusps and lingual surfaces of the teeth may be an indicator of related gastroesophageal reflux.

• The development of orofacial pain, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction symptoms, masticatory muscle fatigue noted on awakening, or morning headache can be related to the positioning of the mandible to open a person’s airway. This topic is addressed in Chapter 27 of this edition of this textbook, where comprehensive diagnostic references can also be found.

• During the evaluation of the oropharynx, prominent tonsils, a large uvula, or a narrow or tongue-obstructed airway may be noted. The patient’s age may contribute to the loss of tone of the pharyngeal muscles.

• Evidence of mouth breathing while sleeping may take the form of drying of the surface of the gingiva.

Sleep, Breathing, and Apnea

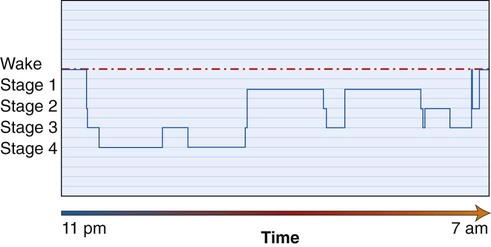

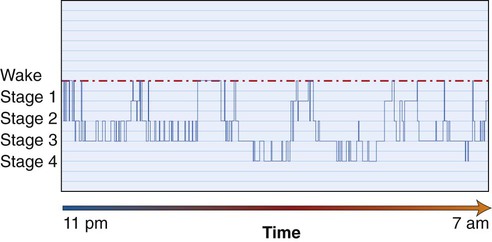

Normal sleep progresses through different stages that are typically depicted on a hypnogram (Figure 28-1).

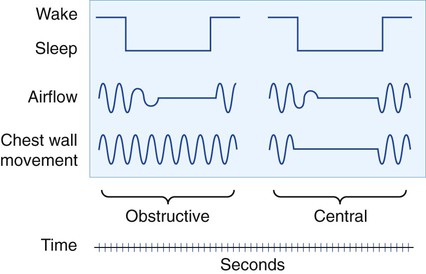

There comes a point at which the increased inspiratory effort or the oxygen desaturation that may accompany the apneic episode is sensed by the sleeping brain, and a transient arousal will be provoked. This is a brief awakening to breathe before the individual returns to sleep. These arousals can be seen in Figure 28-2 as decreased-duration periods and increasingly frequent interruptions in the descent into deeper more refreshing sleep. Disregarding complaints about the snoring noise, these repetitive arousals occur for the most part without the individual being aware, sometimes several hundred times a night.

Each apneic episode may last from a few seconds to approximately 2 minutes. The individual’s descent into the deeper and more restorative slow-wave stages of sleep is interrupted, because he or she has partially awakened to restore the airway. Sleep becomes highly fragmented, and the consequent daytime sleepiness known as hypersomnolence increases the individual’s risk of accidents at home, at work, and on the road.50

OSA has a significant impact on an individual’s quality of life.10 If left untreated, it has neurologic and physiologic consequences,37 including increased morbidity and mortality35 and, particularly for men, impaired cardiovascular51 and metabolic18 function.

Prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea affects a large number of people, but it continues to be largely unrecognized. Estimates suggest that 24% of men and 9% of women who are 30 to 60 years old with an average body mass index of 25 kg/m2 to 28 kg/m2 are affected.49 When considered within the context of the concurrent metabolic dysfunction epidemic (which is manifest in obesity, cardiovascular disease,31,26 and type 2 diabetes in men12,40,39), the prevalence of sleep apnea becomes alarming. Indeed, the International Diabetes Federation urges health care professionals to ensure that a person diagnosed with OSA is considered for the presence of type 2 diabetes and vice versa.41

Central, Mixed, and Complex Apnea

In contrast with OSA, central sleep apnea (CSA) occurs without a physical obstruction of the airway. CSA is caused by a group of disorders that are characterized by the intermittent loss of the respiratory drive (in Figure 28-3, note the lack of chest wall movement in the patient with CSA). Cheyne-Stokes respirations as a form of CSA are most often seen in patients with heart failure. Mixed apnea is, as expected, a combination of OSA and CSA. Complex apnea occurs when CSA events emerge in response to PAP therapy for OSA.17

This chapter is confined to OSA because it is by far the most common form of apnea, and it is in the provision of oral devices (also known as mandibular repositioning devices [MRDs]) for OSA that the suitably trained dentist may play a role.22

Chronic Disease

The maintenance of a separate “silo” approach and viewing one aspect of an individual’s symptomatology in isolation could be argued to be flawed thinking. OSA in isolation and as a potential component of metabolic syndrome (i.e., syndrome Z47) requires a multidisciplinary chronic disease management approach. The World Health Organization48 states that chronic diseases are projected to be the leading cause of disability; if they are not successfully prevented and managed by 2020, they will become the most expensive problems for health care systems.

Diagnosis of Obstructive Sleep Apnea

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, a multidisciplinary team approach for the diagnosis and treatment of OSA is necessary. Dentists are experts when it comes to mouths and should be recognized as such. For OSA treatment, dentists need to build relationships with physicians so that they may, when appropriate, provide a dental solution to a medical condition; however, it is important to recognize that the diagnosis of OSA is not within the purview of dentistry.7

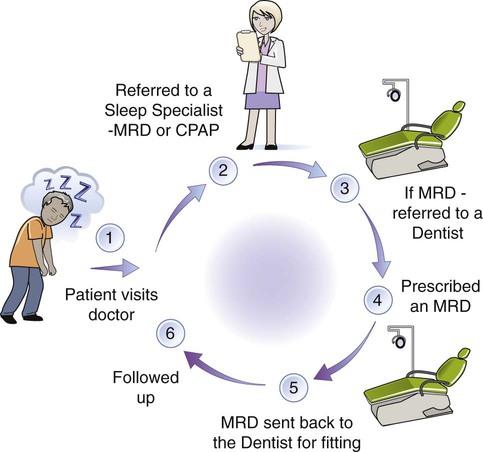

The closest thing to internationally accepted practice parameters, which are those issued by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine,14 state that the “presence or absence and severity of OSA must be determined before initiating treatment.” In practice, this means that a dentist must not initiate treatment with an oral device unless the patient has been assessed, medically diagnosed, and then referred to the dentist (Figure 28-4).

Several screening protocols have been proposed over the years.24,20 In January 2012, the California Dental Association8 determined that it is appropriate for dentists to screen patients for the signs and symptoms of SDB and to work with physicians to diagnose and treat SDB. The Association also stated that SDB is a medical condition, and its diagnosis is outside of the scope of the practice of dentistry.

Whether a PSG is essential to diagnose OSA is now being questioned.36 Since 2009 in the United Kingdom, a general dental practitioner working as part of a multidisciplinary team (including a sleep medicine specialist) may in certain defined circumstances screen, recognize, and initiate treatment with an MRD without a prior medical diagnosis.45 Currently in the United States, both PSG and home study monitor results need to be interpreted by a physician.

• Increasingly valid and competitively priced home sleep testing equipment

• Increase in the number of patients requiring assessment

• Perception that PSG is the point of contention in the treatment process

• Realization that oral devices are appropriate for milder forms of OSA and that dentists are uniquely placed to provide them because they may see the patient more frequently than sleep medicine specialists will see the patient

• Realization that a trained dentist, as part of a multidisciplinary team, may filter referrals to the sleep medicine specialist

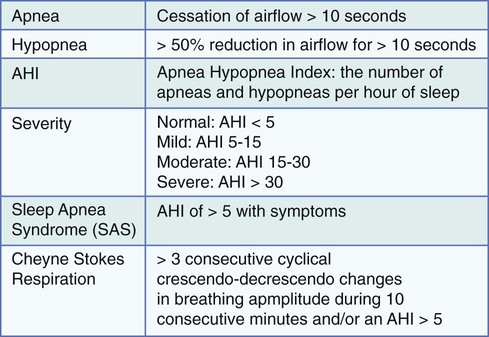

Figure 28-5 provides definitions and diagnostic criteria for SDB.44

Treatment Options for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Otolaryngology or Oromaxillofacial Surgery

Surgical options for snoring and OSA are largely outside of the scope of this text. However, it is important to note that, when physical obstructions to the airway are present (e.g., tonsils, deviated septum, nasal polyps) surgical correction may improve breathing. For example, if adenotonsillar hypertrophy exists, then childhood correction is considered advantageous.30

Limited evidence for adult palatal surgery, which is known as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, exists; this surgery should be considered only after PAP therapy has failed.6 Maxillary or bimaxillary orthognathic surgery is rarely considered, whereas tracheotomy is an effective option of last resort, because it completely bypasses the affected area.

Positive Airway Pressure

PAP (Figure 28-6) is considered the first-line treatment for OSA, and it is very effective in terms of helping the patient to overcome daytime sleepiness symptoms. Individuals with severe sleep apnea do well with this therapy, despite the forbidding appearance. Possibly considered an arduous therapy, it involves wearing a mask over the nose (and sometimes both the mouth and nose) at night while being connected to a quiet blower. It works by slightly pressurizing the upper airway, thereby pneumatically splinting it open and thus preventing it from collapsing. PAP is particularly useful when there is a need for the rapid control of OSA.

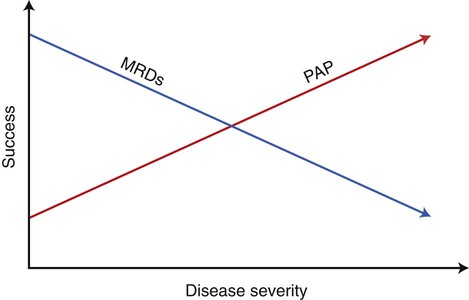

The sleep laboratory may also suggest that oral device therapy is appropriate. This depends on the severity of the OSA and the existence of other comorbidities. Oral devices may be used to provide therapy for sleep apnea of all severities; however, effective results are considered less certain with increasing severity.19 PAP and MRD therapies are complementary; in patients with moderate OSA, the two modalities may, in some circumstances, be considered equally appropriate. Figure 28-7 illustrates this point in broad terms. Treatment of severe sleep apnea with an oral device necessitates careful patient monitoring, because things such as small weight changes may negate the effect.34

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses