Local Anesthesia and Oral Surgery in Children

Local Anesthesia In Children

Topical Anesthesia

A small amount of topical anesthetic should be applied with a cotton-tipped applicator to a mucosa that has been adequately dried and isolated with a 2 × 2 inch cotton gauze pad (Figure 28-1). The time required for the topical anesthetic to reach its full effectiveness may vary from 30 seconds to 5 minutes. Although a toxic response to topical anesthesia is rare, application of an excessive amount should be avoided.1

General Considerations for Local Anesthesia

The mechanism of action of local anesthetics has been further elucidated in recent years. As described in Chapter 7 the evidence supports the notion that local anesthetics penetrate neurons, attach to intraneural receptor sites, and mediate configurable changes of sodium receptors in the neuronal membrane that subsequently block sodium channels. The net result is inhibition of neuronal excitability, which reduces the likelihood of action potential transmission. Therefore local anesthetics alter the reactivity of neural membranes to propagated action potentials that may be generated in tissues distal to the anesthetic block. Action potentials that enter an area of adequately anesthetized nervous tissue are blocked and fail to transmit information to the central nervous system (CNS).2

Local anesthesia may be obtained anatomically by one of three means:

1. The nerve block, which is the placement of anesthetic on or near a main nerve trunk. This results in a wide area of tissue anesthesia.

2. The field block, which is the placement of anesthetic on secondary branches of a main nerve.

3. Local infiltration, which is the deposition of the anesthetic on terminal branches of a nerve. Adequate diffusion of local anesthetic from local infiltration readily occurs in children because their bones are less dense than those of adults.

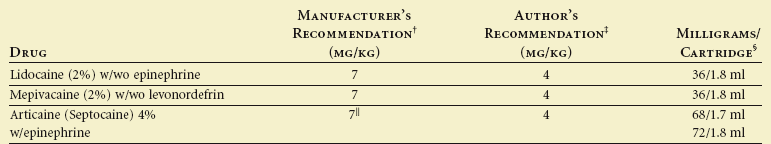

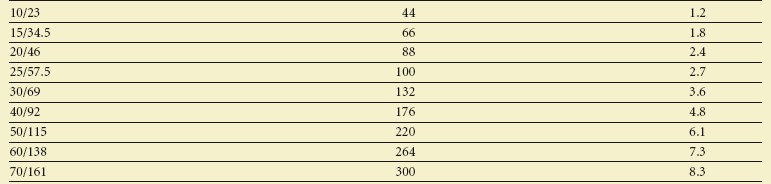

Local anesthetics used in dentistry are classified as esters or amides. Amides are used more frequently because of their reduced allergenic characteristics and greater potency at lower concentrations. The concentration of the different agents varies, and care must be taken to prevent overdose (Table 28-1). As an example, two full cartridges (carpules) of 2% lidocaine (Xylocaine) without vasoconstrictor may be easily tolerated by an adult, but the same amount exceeds the maximal allowable dosage (2 mg/lb body weight) for a 20-pound child. Great care must be taken when a 4% concentration of a local anesthetic (e.g., articaine) is used with children because the amount of local anesthetic is twice that of a 2% solution.

TABLE 28-1

TABLE 28-1

Maximum Recommended Doses of Local Anesthetics for Children*

*Maximum recommended dose means up to, but not exceeding the dose.

†Read manufacturer’s recommendations in package insert.

‡Conservative and safe, yet adequate for most cases.

§2% = 20 mg/ml, thus 1.8 ml/cartridge = 36 mg.

||Safety not established for children less than 4 years of age.

Local anesthetic cartridges (1.8 ml or 1.7 ml) also contain preservatives, organic salts, and sometimes vasoconstrictors. The preservatives (e.g., methylparaben) may be a source of allergic reactions. Concern about rubber products in local anesthetic cartridges as a source of allergic reactions has not been supported by any studies or case reports.3 The vasoconstrictors (e.g., epinephrine) are used to constrict blood vessels, counteract the vasodilatory effects of the local anesthetic, and prolong the duration of the anesthetic.

Operator Technique

The role of the dental assistant is important during transfer of the syringe and in anticipation of patient movement. During the transfer of the syringe from the assistant to the dentist, the child’s eyes tend to follow the dentist’s. The eyes of the dentist should be focused on the face of the patient (Figure 28-2). The hand of the dentist that is to receive the syringe is extended close to the head or body of the child. The body of the syringe is placed between the index and middle finger, with the ring of the plunger slipped over the dentist’s thumb by the assistant. The plastic sheath protecting the needle is then removed by the assistant. The dentist’s peripheral vision guides the syringe to the mouth in a slow, smooth movement.

Reflexive movements of the child’s head and body should be anticipated.4 The head can be stabilized by being held firmly but gently between the body and arm or hand of the dentist. The assistant passively extends his or her arm across the child’s chest so that potential arm and body movements can be intercepted. The area of soft tissue that is to receive the injection is reflected by the free hand of the dentist. The hand can also be used to block the vision of the child as the syringe approaches the mouth. Once tissue penetration by the needle has occurred, the needle should not be retracted in response to the child’s reactions. Otherwise, the child’s behavior may deteriorate significantly if he or she anticipates reinjection. Use of finger rests is strongly advocated.

A short (20 mm) or long (32 mm), 27- or 30-gauge needle may be used for most intraoral injections in children, including mandibular blocks. There apparently is little difference in discomfort level between the 25-gauge and 30-gauge needles for inferior alveolar injections; thus the 27-gauge needle would seem less likely to break or bend during injections and is preferred.5 An extrashort (10 mm), 30-gauge needle is appropriate for maxillary anterior injections.

Maxillary Primary and Permanent Molar Anesthesia

In anesthetizing the maxillary primary molars or permanent premolars, the needle should penetrate the mucobuccal fold and be inserted to a depth that approximates that of the apices of the buccal roots of the teeth (Figure 28-3). The solution should be deposited adjacent to the bone. The maxillary permanent molars may be anesthetized with a posterior superior alveolar nerve block or by local infiltration.

Maxillary Primary and Permanent Incisor and Canine Anesthesia

The innervation of maxillary primary and permanent incisors and canines is by the anterosuperior alveolar branch of the maxillary nerve. Labial infiltration commonly is used to anesthetize the primary anterior teeth. The needle is inserted in the mucobuccal fold to a depth that approximates that of the apices of the buccal roots of the teeth (Figure 28-4). Rapid deposition of the solution in this area is contraindicated because it produces discomfort during rapid expansion of the tissue. The innervation of the anterior teeth may arise from the opposite side of the midline. Thus it may be necessary to deposit some solution adjacent to the apex of the contralateral central incisor.

Palatal Tissue Anesthesia

The tissues of the hard palate are innervated by the anterior palatine and nasal palatine nerves. Surgical procedures involving palatal tissues usually require a nasal palatine nerve block (Figure 28-5) or anterior palatine anesthesia (Figure 28-6). These nerve blocks are painful, and care should be taken to prepare the child adequately. These injections are not usually required for normal restorative procedures unless the procedure involves palatal tissue. However, if it is anticipated that the rubber dam clamp will impinge on the palatal tissue, a drop of anesthetic solution should be deposited into the marginal tissue adjacent to the lingual aspect of the tooth. Blanching of the tissue will be observed.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline

FIGURE 28-1

FIGURE 28-1

FIGURE 28-2

FIGURE 28-2

FIGURE 28-3

FIGURE 28-3

FIGURE 28-4

FIGURE 28-4

FIGURE 28-5

FIGURE 28-5

FIGURE 28-6

FIGURE 28-6