Chapter 27

Neurologic Disorders

Neurologic diseases are common in the general population and therefore are commonly encountered in dental patients. Several diseases affecting the nervous system are of clinical significance in dental practice. Such diseases may vary in severity and consequences. The focus of this chapter is on five of the more important neurologic diseases—epilepsy, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis (MS). Also discussed are cerebrospinal fluid shunts, because of the assumed risk of bacterial seeding after an invasive dental procedure in patients with such shunts.

Epilepsy

Definition

The term epilepsy includes disorders or syndromes with widely variable pathophysiologic findings, clinical manifestations, treatments, and outcomes.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Seizures are characterized by discrete episodes, which tend to be recurrent and often are unprovoked, in which movement, sensation, behavior, perception, and consciousness are disturbed. Symptoms are produced by excessive temporary neuronal discharging, which may result from intracranial or extracranial causes.

Although seizures are required for the diagnosis of epilepsy, not all seizures imply presence of epilepsy. Seizures may occur during many medical or neurologic illnesses, including stress, sleep deprivation, fever, alcohol or drug withdrawal, and syncope.

Box 27-1

Classification of Epileptic Syndromes and Seizure Types

Epileptic Syndromes

Data from Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures, Epilepsia 22:489-501, 1981.

Epidemiology

Epilepsy, which is the most common chronic neurologic condition, affects people of all ages, with a peak incidence in childhood and old age. In the United States, the incidence of all types of epilepsy is 35 to 52 cases per 100,000 population, varying by age: 60 to 70 per 100,000 per year in young children (younger than 5 years of age), 45 per 100,000 in adolescents, as low as 30 per 100,000 in the early adult years, but rising through the sixth and seventh decades back to 60 to 70 per 100,000 and reaching as high as 150 to 200 per 100,000 in persons older than 75 years. The incidence in males is higher at every age. Estimates of the prevalence of epilepsy range from 4.7 to 6.9 per 1000, but its prevalence is much higher in less developed countries for all age groups.

Approximately 10% of the population will have at least one epileptic seizure in a lifetime, and 2% to 4% will experience recurrent seizures at some point.

Etiology

Epileptic seizures are idiopathic in more than half of all affected patients.

Seizures sometimes can be evoked by specific stimuli. Approximately 1 of 15 patients reports that seizures occurred after exposure to flickering lights, monotonous sounds, music, or a loud noise.

Pathophysiology and Complications

The basic event underlying an epileptic seizure is an excessive focal neuronal discharge that spreads to thalamic and brain stem nuclei. The cause of this abnormal electrical activity is not precisely known, although a number of theories have been put forth.

Approximately 60% to 80% of patients with epilepsy achieve complete control over their seizures within 5 years; the remainder achieve only partial or poor control.

Status Epilepticus

A serious acute complication of epilepsy (especially the tonic-clonic type) is the occurrence of repeated seizures over a short time without a recovery period, called status epilepticus. This condition most frequently is caused by abrupt withdrawal of anticonvulsant medication or an abused substance but may be triggered by infection, neoplasm, or trauma. Status epilepticus constitutes a medical emergency.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical manifestations of generalized tonic-clonic convulsions (grand mal seizures) are classic. An aura (a momentary sensory alteration that produces an unusual smell or visual disturbance) precedes the convulsion in one third of patients. Irritability is another premonitory signal. After the aura warning, the patient emits a sudden “epileptic cry” (caused by spasm of the diaphragmatic muscles) and immediately loses consciousness. The tonic phase consists of generalized muscle rigidity, pupil dilation, rolling of the eyes upward or to the side, and loss of consciousness. Breathing may stop because of spasm of respiratory muscles.

Laboratory Findings

The diagnosis of epilepsy generally is based on the history of seizures and presence of abnormalities on the electroencephalogram (EEG).

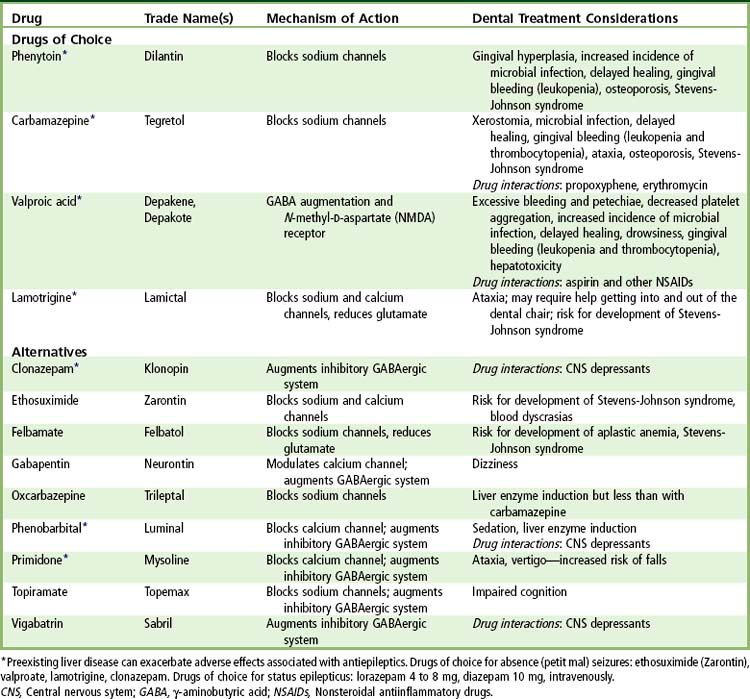

Medical Management

The medical management of epilepsy usually is based on long-term drug therapy. Phenytoin (Dilantin), carbamazepine (Tegretol), and valproic acid are considered first-line agents for treatment of this disease. Several other drugs are available for control of generalized tonic-clonic seizures

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is reserved for patients who have been unable to achieve satisfactory seizure control with several medications, and it is an option for some before brain surgery. The mechanism of VNS is similar to that of an implantable cardiac pacemaker, in which a subcutaneous pulse generator is implanted in the left chest wall and delivers electrical signals to the left vagus nerve through a bipolar lead. The stimulated vagus nerve provides direct projection to regions in the brain potentially responsible for the seizure. The VNS device generally is used in combination with antiepileptic medications.

Dental Management

Medical Considerations

The first step in the management of an epileptic dental patient is identification of the patient as having the disorder (

Box 27-2 Dental Management

Considerations in Patients with Seizure Disorders

Patient Evaluation/Risk Assessment (see

Potential Issues/Factors of Concern

Fortunately, most epileptic patients are able to attain good control of their seizures with anticonvulsant drugs and are therefore able to receive normal routine dental care. In some instances, however, the history may reveal a degree of seizure activity that suggests noncompliance or a severe seizure disorder that does not respond to anticonvulsants. For these patients, a consultation with the physician is advised before dental treatment is rendered. A patient with poorly controlled disease may require additional anticonvulsant or sedative medication, as directed by the physician.

Patients who take anticonvulsants may suffer from the toxic effects of these drugs, and the dentist should be aware of these manifestations. In addition to the more common adverse effects (see

Propoxyphene and erythromycin should not be administered to patients who are taking carbamazepine because of interference with metabolism of carbamazepine, which could lead to toxic levels of the anticonvulsant drug.

Seizure Management

Despite consistent use of appropriate preventive measures by both dentist and patient, the possibility always exists that an epileptic patient may experience a generalized tonic-clonic convulsion in the dental office. The dentist and office staff members should anticipate and be prepared for such events. Preventive measures include knowing the patient’s history, scheduling the patient at a time within a few hours of taking the anticonvulsant medication, using a mouth prop, removing dentures, and discussing with the patient the urgency of mentioning an aura as soon as it is sensed. The clinician also should be aware that irritability often is a symptom of impending seizure. With a premonitory stage of sufficient duration, 0.5 to 2 mg of lorazepam can be given sublingually, or diazepam 2 to 10 mg can be given intravenously.

If the patient has a seizure while in the dental chair, the primary task of management is to protect the patient and try to prevent injury. No attempt should be made to move the patient to the floor. Instead, the instruments and instrument tray should be cleared from the area, and the chair should be placed in a supported supine position (

FIGURE 27-1 Dental chair in the supine position with the back supported by the operator’s or assistant’s stool.

If a mouth prop (e.g., a padded tongue blade between the teeth to prevent tongue biting) is used, it should be inserted at the beginning of the dental procedure (see

A grand mal seizure generally does not last longer than a few minutes. Afterward, the patient may fall into a deep sleep from which he or she cannot be aroused. Oxygen (100%), maintenance of a patent airway, and mouth suction should be provided during this phase. Alternatively, the patient can be turned to the side to control the airway and to minimize aspiration of secretions. Within a few minutes, the patient gradually regains consciousness but may be confused, disoriented, and embarrassed. Headache is a prominent feature during this period. If the patient does not respond within a few minutes, the seizure may be associated with low serum glucose, and delivery of glucose may be needed.

No further dental treatment should be attempted after a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, although examination for sustained injuries (e.g., lacerations, fractures) should be performed. In the event of avulsed or fractured teeth (

FIGURE 27-2 Fracture of teeth and laceration of lower lip sustained during a grand mal seizure.

(Courtesy Gerald A. Ferretti, DDS, Lexington, Kentucky.)

In the event that a seizure becomes prolonged (status epilepticus) or is repeated, intravenous lorazepam (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) 4 to 8 mg, or 10 mg diazepam, generally is effective in controlling it. Lorazepam is preferred by many experts because it is more efficacious and lasts longer than diazepam.

Treatment Planning Considerations

Because gingival overgrowth is associated with phenytoin administration, every effort should be made to maintain a patient at an optimal level of oral hygiene. This may require frequent visits for monitoring of progress. If gingival overgrowth is significant, surgical reduction will be necessary. This correction must be accompanied by an increased awareness of oral hygiene needs and a positive commitment by the patient to maintain oral cleanliness.

A missing tooth or teeth should be replaced if possible to prevent the tongue from being caught in the edentulous space during a seizure (as commonly happens). Generally, a fixed prosthesis or implant is preferable to a removable one. (The removable prosthesis becomes dislodged more easily.) For fixed prostheses, all-metal units should be considered when possible, to minimize the chance of fracture. When placing anterior castings, the dentist may wish to consider using three-quarter crowns or retentive nonporcelain facings.

Removable prostheses are, nevertheless sometimes constructed for epileptic patients. Metallic palates and bases are preferable to all-acrylic ones. If acrylic is used, it should be reinforced with wire mesh.

Oral Complications and Manifestations

The most significant oral complication seen in epileptic patients is gingival overgrowth, which is associated with phenytoin (

Meticulous oral hygiene is important for preventing overgrowth and significantly decreasing its severity. Good home care must always be combined with the removal of irritants, such as overhanging restorations and calculus. Frequently, enlarged tissues interfere with function or appearance, and surgical reduction may become necessary.

Traumatic injuries such as broken teeth, tongue lacerations, and lip scars also are common in patients who experience generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Stomatitis, erythema multiforme, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are rare adverse effects associated with the use of phenytoin, valproic acid, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine. These complications are more common during the first 8 weeks of treatment.

Stroke (Cerebrovascular Accident)

Definition

Stroke is a generic term that is used to refer to a cerebrovascular accident (CVA)—a serious and often fatal neurologic event caused by sudden interruption of oxygenated blood to the brain. The associated ischemic injury results in focal necrosis of brain tissue, which may be fatal if the damage is catastrophic. Even if a stroke is not fatal, the survivor often is to some degree debilitated in motor function, speech, or cognition. The scope and gravity of stroke are reflected in the fact that stroke is the leading cause of serious, long-term disability in the United States; 5% of the population older than 65 years of age has had one stroke.

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

Stroke is one of the most significant health problems in the United States. Stroke is the third leading cause of death (behind heart disease and cancer) in the United States, with 275,000 Americans dying of stroke annually.

Hypertension is the most important risk factor for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

Approximately 7% to 10% of men and 5% to 7% of women older than 65 years have asymptomatic carotid stenosis of greater than 50%. Epidemiologic studies suggest that the rate of unheralded stroke evolving ipsilateral to a stenosis is about 1% to 2% annually.

Nonvalvar atrial fibrillation carries a 3% to 5% annual risk for stroke, with the risk becoming even higher in the presence of advanced age, previous transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke, hypertension, impaired left ventricular function, and diabetes mellitus.

In epidemiologic studies, the risk for stroke in smokers is almost double that in nonsmokers, but the risk becomes essentially identical to that in nonsmokers by 2 to 5 years after quitting. The relative risk for stroke is two to six times greater for patients with insulin-dependent (type 1) diabetes.

Etiology

Stroke is caused by the interruption of blood supply and oxygen to the brain as a result of ischemia or hemorrhage. The most common type is ischemic stroke induced by thrombosis (in 60% to 80% of cases) of a cerebral vessel. Ischemic stroke also can result from occlusion of a cerebral blood vessel by distant emboli. Hemorrhage causes about 15% of all strokes and carries a 1-year mortality rate greater than 60%.

Cerebrovascular disease is the primary factor associated with stroke. Atherosclerosis and cardiac pathosis (myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation) increase the risk of thrombolic and embolic strokes, whereas hypertension is the most important risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke.

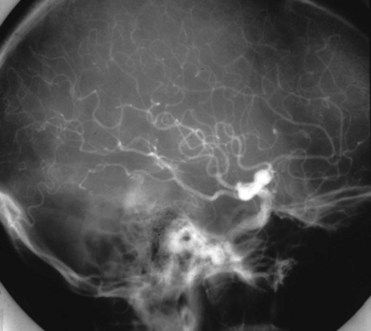

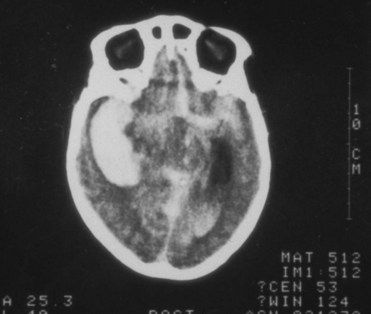

Pathophysiology and Complications

Pathologic changes associated with stroke result from infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral infarctions most commonly are caused by atherosclerotic thrombi or emboli of cardiac origin. The extent of an infarction is determined by a number of factors, including site of the occlusion, size of the occluded vessel, duration of the occlusion, and collateral circulation. The production and circulation of proinflammatory cytokines, the occurrence of clotting factors, and arterial inflammation contribute to platelet aggregation. Neurologic abnormalities result from excitotoxicity, free radical accumulation, inflammation, mitochondrial and DNA damage, and apoptosis of the region supplied by the damaged artery.

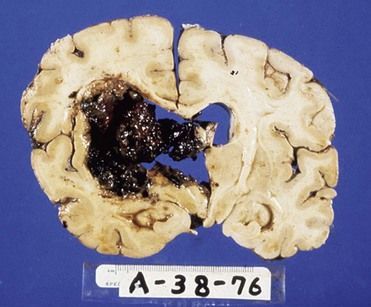

The most common cause of intracerebral hemorrhage is hypertensive atherosclerosis, which results in microaneurysms of the arterioles (

The most serious outcome of stroke is death, which occurs in 8% of those who experience ischemic strokes and 38% to 47% of those with hemorrhagic strokes within a month of the event. Overall, about 23% of patients die within 1 year.

If the victim survives, it is highly likely that a neurologic deficit or disability of varying degree and duration will remain. Of those who survive the stroke, 10% recover with no impairment, 50% have a mild residual disability, 15% to 30% are disabled and require special services, and 10% to 20% require institutionalization. Approximately 50% of those who survive the acute period (the first 6 months) are alive 7 years later.

The type of residual deficit that results from a stroke is directly dependent on the size and location of the infarct or hemorrhage. Deficits include unilateral paralysis, numbness, sensory impairment, dysphasia, blindness, diplopia, dizziness, and dysarthria. Return of function is unpredictable and usually takes place slowly, over several months. Even with improvement, patients frequently are left with some permanent residual problem, such as difficulty in walking, using the hands, performing skilled acts, or speaking. Dementia also may be an outcome of stroke.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Familiarity with the warning signs and symptoms and the phases of stroke can lead to appropriate action that may be lifesaving. Four events associated with stroke are (1) the transient ischemic attack (TIA), (2) reversible ischemic neurologic deficit (RIND), (3) stroke-in-evolution, and (4) the completed stroke. These events are defined principally by their duration.

A TIA is a “mini” stroke that is caused by a temporary disturbance in blood supply to a localized area of the brain. A TIA often is associated with numbness of the face, arm, or leg on one side of the body (hemiplegia); weakness, tingling, numbness, or speech disturbances that usually last less than 10 minutes. Most commonly, a major stroke is preceded by one or two TIAs within several days of the first attack.

A RIND is a neurologic deficit that is similar to a TIA but does not clear within 24 hours. Eventual recovery is the rule, however.

Stroke-in-evolution is a neurologic condition that is caused by occlusion or hemorrhage of a cerebral artery in which the deficit has been present for several hours and continues to worsen during a period of observation. Signs of stroke include hemiplegia, temporary loss of speech or trouble in speaking or understanding speech, temporary dimness or loss of vision, particularly in one eye (may be confused with migraine), unexplained dizziness, unsteadiness, or a sudden fall.

Clinical manifestations that remain after a stroke vary in accordance with the site and size of residual brain deficits; these include language disorders, hemiplegia, and paresis, a form of paralysis that is associated with loss of sensory function and memory and weakened motor power.

Box 27-3 Manifestations of Right-Sided Versus Left-Sided Brain Damage

| Right-Sided Brain Damage | Left-Sided Brain Damage |

|---|---|

Laboratory Findings

Patients suspected of having had a stroke usually undergo a variety of laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging procedures to rule out conditions that can produce neurologic alterations, such as diabetes mellitus, uremia, abscess, tumor, acute alcoholism, drug poisoning, and extradural hemorrhage.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses