Chapter 18

AIDS, HIV Infection, and Related Conditions

On June 5, 1981, when the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported five cases of Pneumocystis carinii (now jiroveci) pneumonia in young homosexual men in Los Angeles, few suspected that it heralded a pandemic of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In 1983, a retrovirus (later named the human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) was isolated from a patient with AIDS. Since that first report, more than 70 million persons have been infected with HIV, and more than 30 million have died of AIDS.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

AIDS is an infectious disease that is transmitted predominantly through intimate sexual contact and by parenteral means. In view of the nature of this bloodborne pathogen, HIV infection and AIDS have important implications for dental practitioners. Although HIV has rarely been transmitted from patients to health care workers, this may occur, and the patient with HIV infection or AIDS may be medically compromised and may need special dental management considerations. On the basis of current statistics, the average dental practice is predicted to encounter at least two patients infected with HIV per year.

Definition

The definition of AIDS provided by the CDC has been revised several times over the years, and in 2008 it was revised to be laboratory-confirmed evidence of HIV infection in a person who has stage 3 HIV infection (i.e., a CD4+ lymphocyte count less than 200 cells/µL).

Box 18-1 AIDS-Defining Conditions

• Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent

• Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs

• Candidiasis of esophagus

• Cervical cancer, invasive

• Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary

• Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (longer than 1 month in duration)

• Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes), onset at age >1 month

• Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision)

• Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (>1 month’s duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis (onset at age >1 month)

• Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 month’s duration)

• Kaposi sarcoma

• Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia or pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia complex

• Lymphoma, Burkitt (or equivalent term)

• Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term)

• Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii infection, disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of any site, pulmonary,

• Mycobacterium infection, other species or unidentified species, disseminated

• Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

• Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

• Salmonella septicemia, recurrent

• Toxoplasmosis of brain, onset at age >1 month

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Incidence and Prevalence

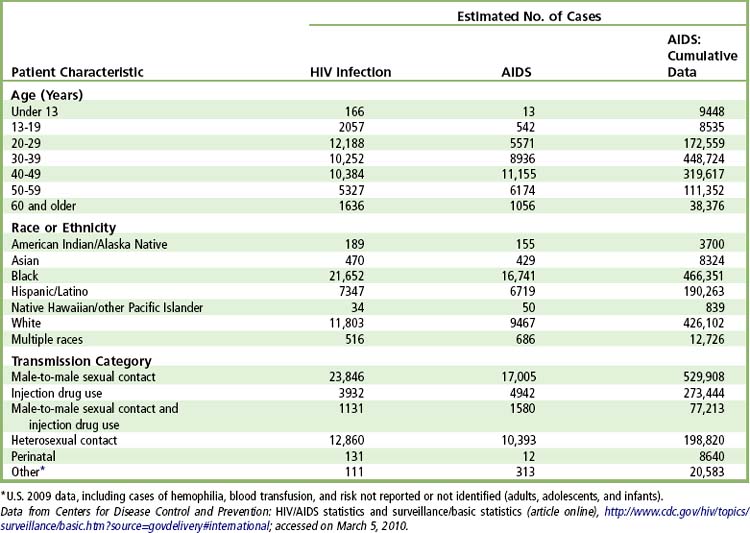

An estimated 2.7 million people across the globe are newly infected with HIV annually. At the end of 2009, there were an estimated 33.4 million persons globally and an estimated 1.1 million persons in the United States who were infected and living with HIV infection/AIDS.

The CDC estimated that approximately 56,300 persons were newly infected with HIV in 2006 and 42,000 were newly infected in 2009.

The estimated number of AIDS diagnoses in the United States for 2009 was approximately 34,000. Adult and adolescent AIDS accounted for about 99% of the cases, 75% of which occurred in males and 25% in females. The cumulative estimated number of AIDS diagnoses through 2009 in the United States was 1.1 million.

Since the introduction of protease inhibitors in 1996 and the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the epidemic of AIDS in the United States has slowed and stabilized. Still, the CDC reports approximately 2250 new cases per month. As of the end of 2006, 565,927 deaths have been reported in the United States due to AIDS, and 14,627 deaths occurred in 2006 alone. Most deaths occur in adults, with few deaths reported in children younger than age 13 in 2006.

Several trends in the epidemiology of AIDS have emerged over the decades. In the United States, peak incidence was in 1993 and peak incidence of death was 50,877 in 1995. The past 2 decades witnessed a decline in the number of cases of AIDS associated with blood and blood products in transfusion and hemophiliac patient groups, specifically attributable to improved testing (starting in 1985) of donor blood for HIV antibodies and the heating of factor VIII replacement preparations. Also, an increase in the ratio of infected women to men occurred a decade ago; this ratio has remained stable in about 25% of women but is particularly higher in the 30- to 40-year age group of black women.

At present there is no effective vaccine to prevent HIV infection, although large research efforts have and continue to be made in this arena. Also, a nonpandemic relating strain of HIV, known as HIV-2, occurs less commonly throughout the world. Most cases of HIV-2 infection have occurred in West Africa, with a limited number of cases occurring in Canada and the United States. Most persons infected with HIV-2 are long-term nonprogressors because viral loads generally are low, and the immunosuppression is not as severe.

Etiology

AIDS is caused by HIV, a nontransforming retrovirus of the lentivirus family. There are two HIV subtypes, HIV-1 and HIV-2, and many strains of each. HIV-1 was first identified in 1983 by Francoise Barre-Sinoussi in the lab of Luc Montaignier of the Pasteur Institute. They first called it lymphadenopathy-associated virus. Within a year of this discovery, a team led by Robert Gallo from the National Institutes of Health isolated a retrovirus identified as the human T lymphotropic virus III (HTLV-III) and labeled it as the etiologic agent for AIDS. In 1984, Jay Levy’s team in San Francisco also isolated a retrovirus, AIDS-related virus (ARV), and designated it as the causative agent for AIDS. All three viruses were similar retroviruses, but minor differences were observed in their amino acid sequences. Variation in disease patterns are attributed to the slight sequence differences among HIV strains, which also makes difficult the production of a vaccine. The three groups essentially were describing the same retrovirus, which can change its antigenicity. Until 1986, most workers in the field referred to the virus as HTLV-III and considered it to be the causative agent for AIDS. In 1986, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that the AIDS virus be called the human immunodeficiency virus

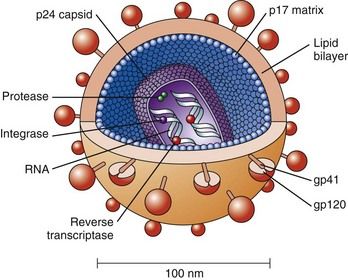

FIGURE 18-1 The structure of human immunodeficiency virus, showing the p24 capsid protein surrounding two strands of viral RNA.

(From Copstead LC, Banasik JL: Pathophysiology, ed 4, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.)

HIV is an enveloped RNA retrovirus about 100 nM in diameter. Glycoproteins (gp41 and gp120) stud the surface of the envelope and serve to bind to human cells (

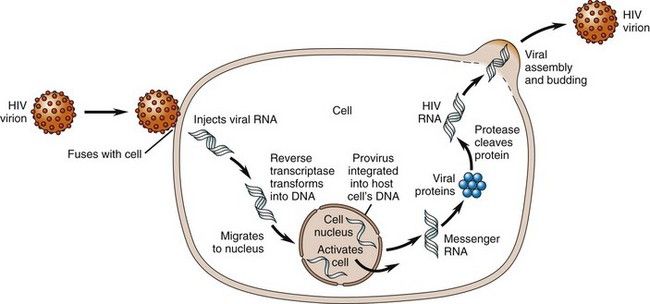

FIGURE 18-2 Life Cycle of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

(From Copstead LC, Banasik JL: Pathophysiology, ed 4, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.)

HIV-1 infection is divided into stages: entry, reverse transcription of RNA to DNA, export of the viral DNA from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and integration into the host chromosome, transcription, translation and cleavage of the polyproteins produced, assembly of virions, and budding of virions. The process is largely regulated by the proteins tat, rev, and nef, which are necessary for viral replication. Virulence has been mapped to the carboxyl-terminal half of the gp120, which has been referred to as the V3 loop.

Pathophysiology and Complications

Transmission of HIV is by exchange of infected bodily fluids from sexual contact and through blood and blood products. The most common method of sexual transmission in the United States is anal intercourse in MSM, in whom the risk of HIV infection is 40 times higher than in other men and in women.

The virus is found in blood, seminal fluid, vaginal secretions, tears, breast milk, cerebrospinal fluid, amniotic fluid, and urine. Blood, semen, breast milk, and vaginal secretions are the main fluids that have been shown to be associated with transmission of the virus.

Vertical transmission to infants born of infected mothers can occur at birth or transplacentally. HIV has been found in saliva, and transmission by transfer of saliva possibly contaminated with blood has been reported from providing premasticated food from HIV-infected parents to infants.

Once HIV has gained access to the bloodstream, the virus selectively seeks out T lymphocytes (specifically T4 or T helper lymphocytes) (see

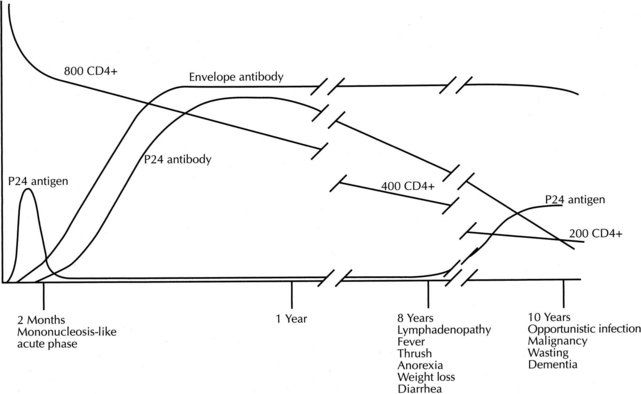

As time progresses, a steady-state viremia develops, and several thousand copies of HIV are present in the blood (

FIGURE 18-3 The natural history of human immunodeficiency virus infection.

(From Brookmeyer R, Gail MH: AIDS epidemiology: a quantitative approach, New York, 1994, Oxford University Press.)

In untreated persons and in persons in whom therapy is ineffective, the CD4+ count continues to decline while HIV proliferates. As the CD4+ count drops and approaches 200 cells/µL, persons can exhibit weight loss, diarrhea, and night sweats (see

Evidence suggests that persons most susceptible to developing AIDS are those with repeated exposure to the virus who also have an immune system that has been challenged by repeated exposure to various antigens (semen, hepatitis B, or blood products).

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

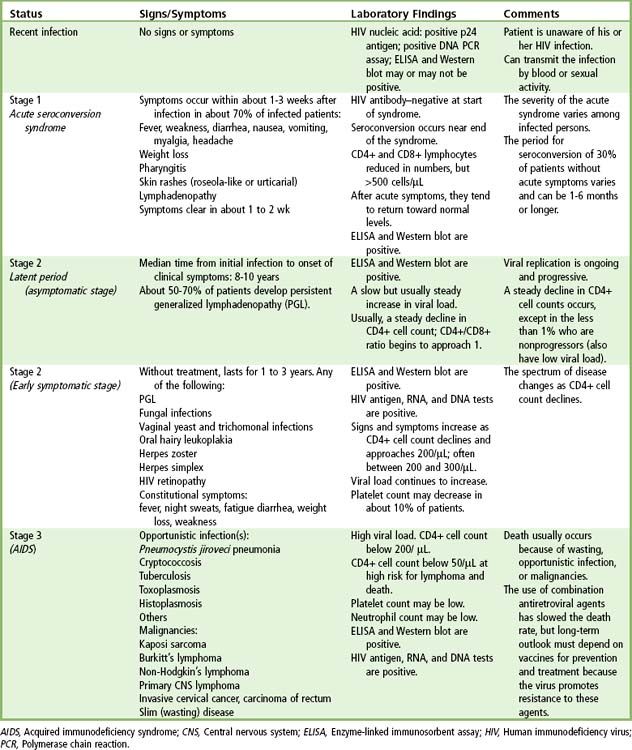

During the first 2 to 6 weeks after initial infection with HIV, more than 50% of patients develop an acute flulike syndrome marked by viremia that may last 10 to 14 days. Others may not manifest this symptom complex. Symptomatic persons often develop lymphadenopathy, fever, pharyngitis and a skin rash but generally do not display circulation antibodies until the 6th week to 6th month. The severity of the initial acute infection with HIV (i.e., level of viremia) is predictive of the course the infection will follow. In one study, 78% of persons with a long-lasting acute illness developed AIDS within 3 years; by contrast, only 10% of those patients with no acute illness at seroconversion developed AIDS within 3 years.

The CDC defines three stages of HIV infection.

Box 18-2 CDC Staging of HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents

Stage 1: Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection, no AIDS-defining conditions and CD4+ T lymphocyte count of ≥500 cells/µL or CD4+ T lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of ≥29.

Stage 2: Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection, no AIDS-defining condition, and laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T lymphocyte count of 200-499 cells/µL or CD4+ T lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of 14-28.

Stage 3 (AIDS): Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T lymphocyte count is <200 cells/µL or CD4+ T lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes is <14 or documentation of an AIDS-defining condition (see

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Laboratory Findings

Most patients exposed to the virus, with or without clinical evidence of disease, show antibodies to the virus by the 6th month of infection. Patients with advanced HIV infection or AIDS have an altered ratio of CD4+/CD8+ lymphocytes, a decrease in total number of lymphocytes, thrombocytopenia, anemia, a slight alteration in the humoral antibody system, and a decreased ability to show delayed allergic reactions to skin testing (cutaneous anergy).

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is the screening test for identification of antibodies to HIV. It is 90% sensitive but has a high rate of false-positive results. Current practice is to screen first with ELISA. If the results are positive, a second ELISA is performed. All positive results are then confirmed with Western blot analysis. This combination of tests is accurate more than 99% of the time. Positive ELISA and Western blot test results indicate only that the individual has been exposed to the AIDS virus. If results of the Western blot are indeterminate, HIV infection is rarely, if ever, present. These tests, however, do not indicate the status of the HIV infection or whether AIDS is present. However, patients with positive results on the ELISA and Western blot test are considered potentially infectious. ELISA testing for HIV in saliva is an alternative approach that is 98% sensitive in detecting antibodies to HIV.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses