Chapter 22

PONTIC DEFECTS

Deformity of the subpontic area can give rise to aesthetic problems. Seibert, in 1983,1 classified ridge defects, as follows:

- Class I – facio-lingual loss of tissue with normal ridge height in an apico-coronal direction.

- Class II – apico-coronal loss of tissue with normal ridge width in a facio-lingual direction.

- Class III – combined facio-lingual and apico-coronal loss of tissue, resulting in a loss of normal height and width.

Management of the Deformity Depends Upon

- The size and type of the deformity.

- How much shows in function.

- Whether the deformity is primarily of soft tissue, bone or tooth.

- The relationship to adjacent teeth.

- The nature of the soft tissue – thick, thin, friable.

- The anticipated prosthetic restoration and its relationship to the opposing arch and edentulous ridge.

- The patient’s concerns, objectives and wishes.

- The clinician’s ability, and availability of specialist support.

Prevention of Defect Formation

- Teeth should be extracted as atraumatically as possible, preserving the labial and lingual cortical plates of bone. Luxators (S. S. White, Hu Friedy) should be used to widen the socket followed by forceps which should be applied and the socket gently widened further using the forceps in a rocking motion, whilst applying axial load.

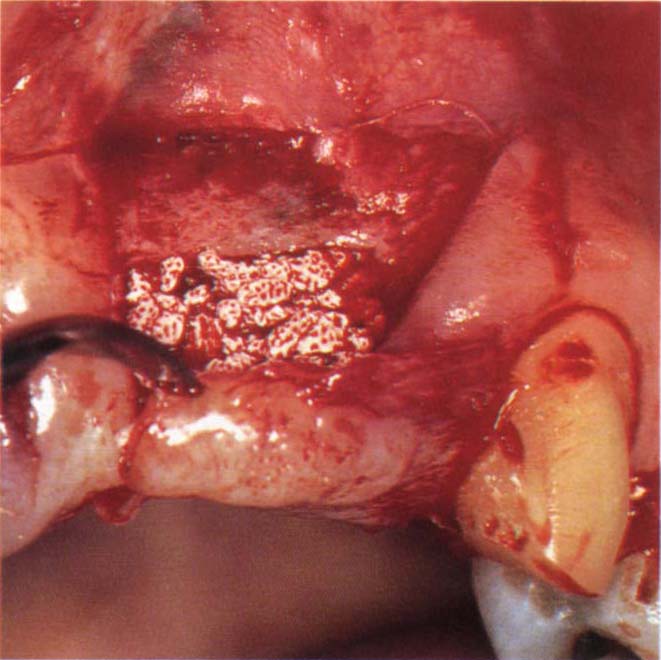

Removal of a tooth which has already lost the labial cortical plate of bone may be followed by the collapse of soft tissue into the socket and subsequent formation of a defect. - Insertion of autografts or allografts, such as hydroxy-apatite crystals, into the socket.

The clinician must acknowledge the biological limitation of hydroxyapatite implants. Its incorporation within alveolar bone may remain, permanently, as a region of diminished blood circulation and curtailed host defense. Osseointegrated fixtures have a poor prognosis if placed in such sites subsequently. Furthermore, the crystals may move with time, leading to altered ridge form.2–4 - Cell exclusion membrane techniques with, or without grafts to fill the socket (Figs 22-1a–e).5

Following extraction, a piece of exclusion membrane is laid over the defect (Fig 21-1c). The rigidity of the membrane usually automatically results in a domed shape which covers the defect. If it appears that the sutured flap will not hold the membrane in place, it is advisable to fix the membrane with bone screws (Memphis screws – Straumann Inst.). It is not usually necessary to use a space filler beneath the membrane following tooth extraction. The membrane prevents downgrowth of epithelium and allows the socket to fill from the base.

Surgical Correction (Fig 22-1)

Seibert, in 1983,1 described a series of surgical procedures to correct such deformities; the techniques are particularly well illustrated in Rosenberg et al. (1988)6 and Bahat and Handelsman (1992).7 The interested reader is also referred to Garber (1981).8

Techniques can be divided into four main categories.9 The indications, advantages and disadvantages of each are described by Bahat and Handelsman (1992).7

- Subepithelial, subconnective tissue or subperiosteal inlay graft of connective tissue, bone or biormaterials such as calcium hydroxyapatite or tricalcium phosphate (Fig 22-1f+h).

- Onlay grafts – thick composite graft of palatal epithelium and connective tissue (Figs 22-1i).

- Pedicle grafts – these can be rotational, that is, the flap is rotated around a pivot point, or advanced, that is, the flap reaches its final site without rotation.7

- Exclusion membranes held away from the underlying bone by screw, titanium fixtures, titanium cages or space filling materials, with the aim of allowing bone regeneration (Figs 22-1j–q).10

One problem in these techniques is flap design, since there must be sufficient soft tissue to cover whatever is placed on the ridge, either the flap must be mobilized or the soft tissue expanded prior to augmentation.11

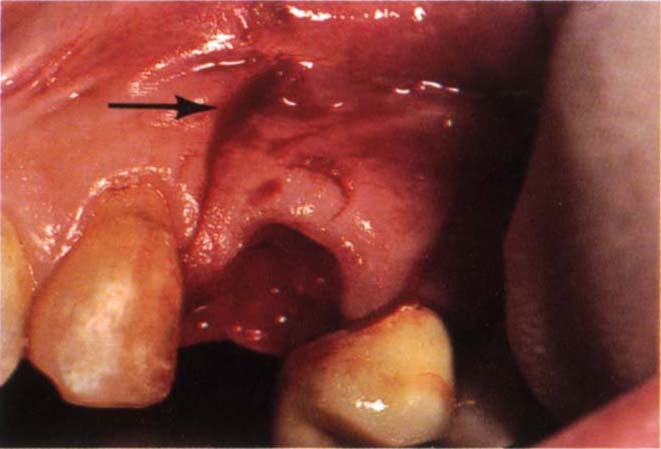

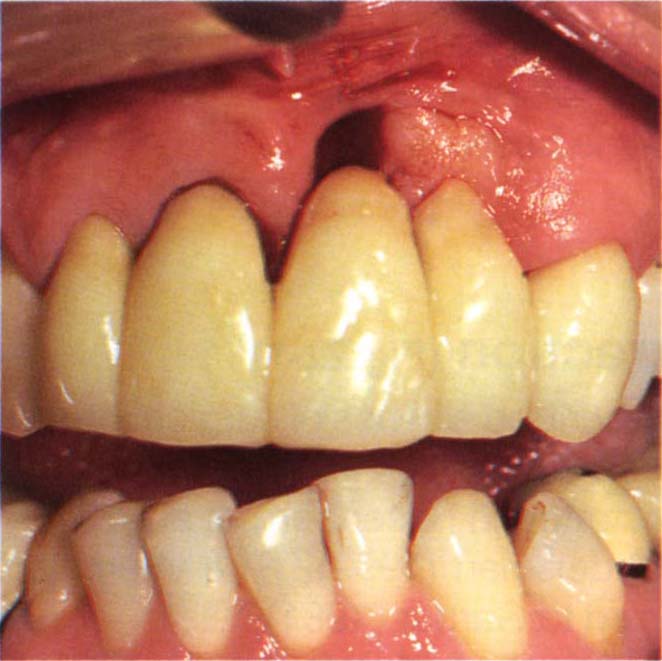

Fig. 22-1a Prevention of a pontic defect. Following a road traffic accident 24 was displaced through the labial plate of bone. The buccally displaced 24 was extracted. The buccal plate of bone had fractured. Two vertical incisions extended into the mucobuccal fold. The incision angles altered at the fold level to incline towards each other, altering the angle to the vertical cut to approximately 100° (arrow). Mucoperiosteal flap elevated. Note that the interdental papilla has not been included in the flap.

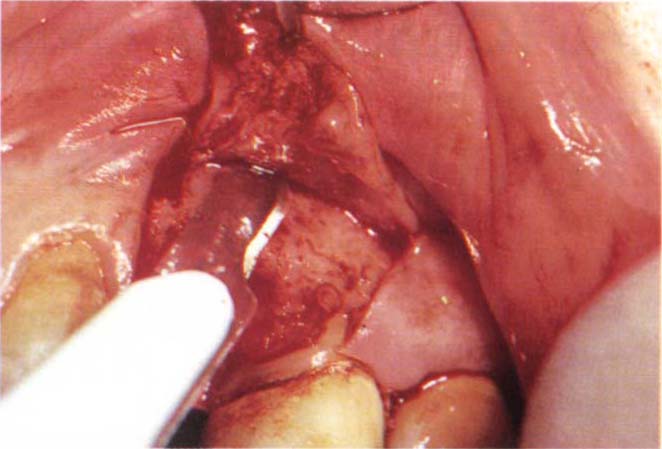

Fig. 22-1b Cutting the periosteum. The flap can now be advanced over the socket.

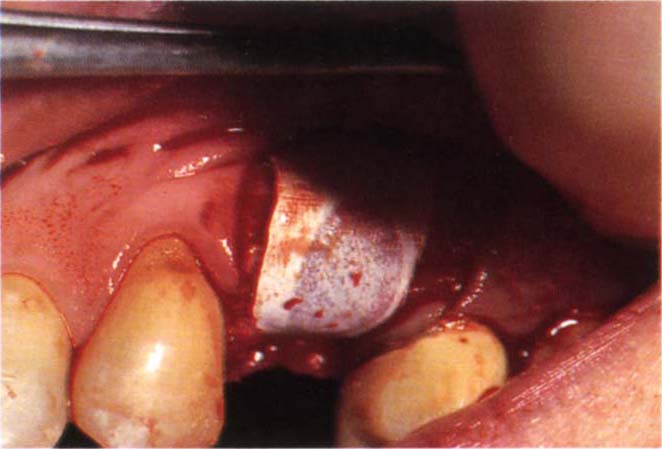

Fig. 22-1c Gore-Tex Oval 4 membrane placed over the socket. A small palatal full thickness flap is raised and the Gore-Tex edge placed beneath the periosteum. This is sufficient to anchor it and cause it to tent out when folded over the labial plate of bone.

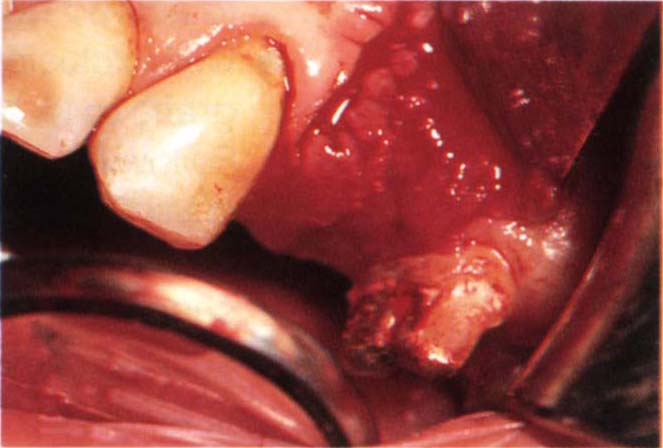

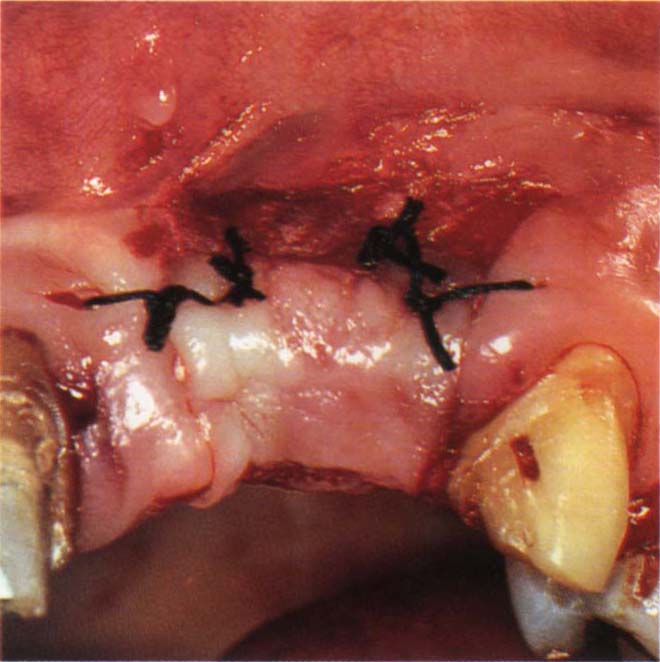

Fig. 22-1d The flap is advanced and sutured and the provisional bridge placed. One week later following suture removal.

Fig. 22-1e Six months later – removal of the Gore-Tex. The ridge form is maintained.

Fig. 22-1f (i) Start.

Fig. 22-1f (ii) Class I – defect facio-lingual loss.

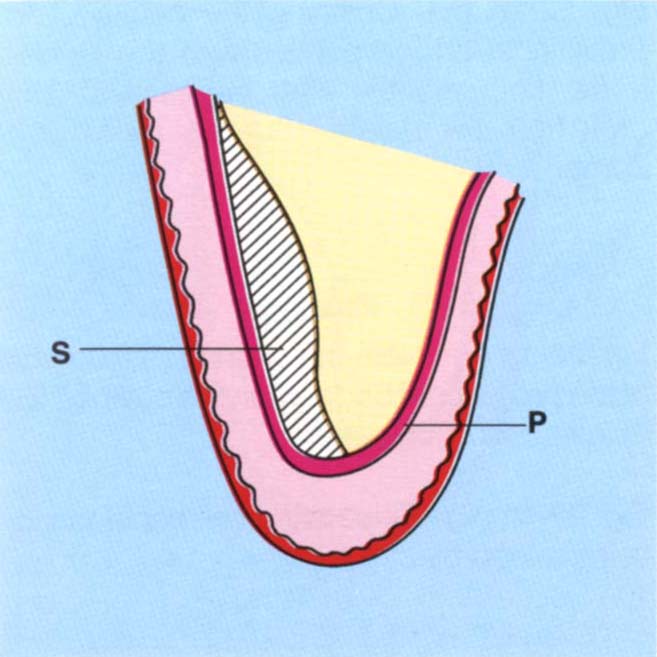

Fig. 22-1g (i) Subperiosteal inlay graft (S). There is good colour match but a risk of loss of the graft through sequestration, particularly if the overlying tissue is thin.

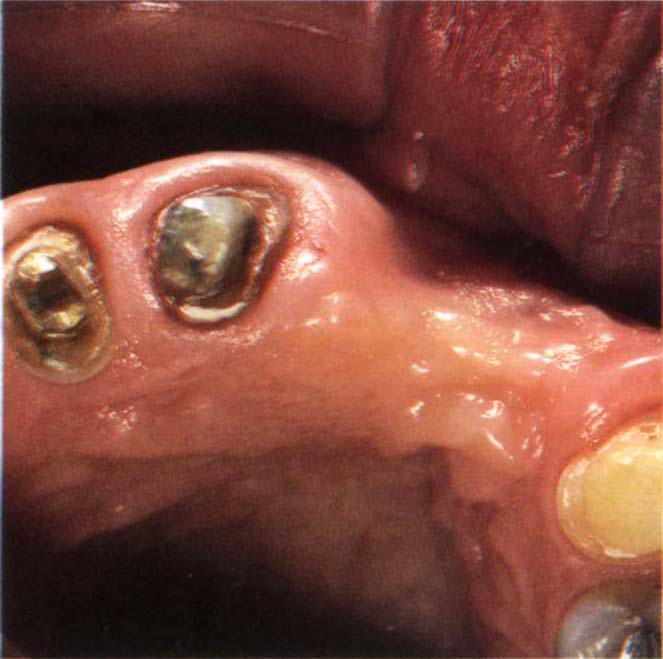

Fig. 22-1g (ii) Hydroxyapatite granules (Interpore 200) being placed. The flap is palately based, full thickness, except for the apical 5 mm where it is split thickness to enable the flap to slide coronally, Figure 22-1g (iii).

Fig. 22-1g (iii) The flap is sutured and the hydroxyapatite retained by periosteum apical and coronal to it. This flap design retains the mucogingival junction but does not provide much soft tissue for deformity correction.

Fig. 22-1g (iv) Note the filling of the defect (surgery by Mr J. S. Zamet).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses