Eruption and Shedding of Teeth

• To name the three stages of active tooth eruption and the points at which each one begins

• To discuss the fate of the epithelial layers covering the crown of the tooth

• To name some of the forces in tooth eruption and which ones most likely have the greatest influence

• To discuss briefly what causes the shedding of primary teeth

• To diagram or describe the origin and position of the permanent teeth as compared with the deciduous teeth

• To list and describe the factors that lead to a retained primary tooth

ACTIVE TOOTH ERUPTION

Preeruptive Stage

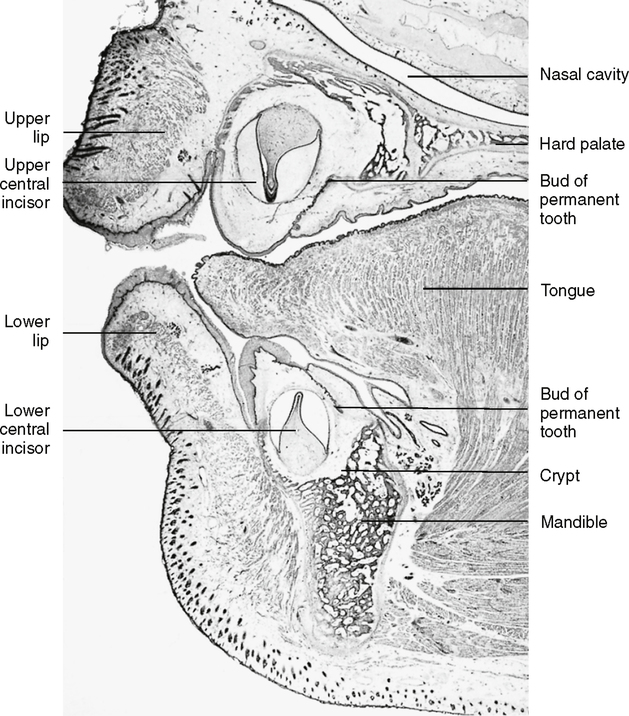

The preeruptive stage begins as the crown starts to develop. Recall that dental lamina formation—bud, cap, and bell stages, as well as the calcification of the crown—takes place in the connective tissue beneath the oral epithelium. During this time the bone of the maxilla or mandible surrounds the developing primary tooth in a U-shaped crypt or beginning socket (Fig. 22-1).

Eruptive Stage

The eruptive stage or prefunctional eruptive stage begins with the development of the root. In Chapter 21 the development of the root and Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath were discussed. The root develops in a crypt of bone. As it begins forming, osteoclasts temporarily may deepen the crypt by resorbing bone at the bottom to accommodate for the increase in root length. While the root continues to lengthen, the tooth begins to move toward the surface of the oral cavity. As it approaches the oral cavity, the alveolar bone is growing to keep pace with it. However, in time the tooth moves faster than the growing alveolar bone and approaches the surface of the oral epithelium and breaks into the oral cavity.

For both primary and secondary dentition, tooth movement in the eruptive stage tends to be occlusal and facial, more facial in the anteriors than in the posteriors. When we think about the pathway for the secondary teeth, we have to consider their mechanism for development. As discussed in Chapter 19, the successional lamina buds off the dental lamina and forms a permanent tooth at its end, still partially attached by the successional lamina. As the permanent

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses