Chapter 20

PERIODONTAL SURGERY

It must be stressed that this section is not intended to be a comprehensive periodontal text. The aim is to provide the restorative dentist with an outline of the possibilities of periodontal surgery and to highlight some of the dilemmas.

The primary indications for periodontal surgery are:

- To gain access for open root debridement.

- To eliminate pockets to:

facilitate plaque removal by the patient;

treat furcation problems;

gain access to caries and sound tooth

tissue beyond the caries;

gain access to a fractured root. - To obtain new attachment.

- To lengthen the clinical crown.

- To improve aesthetics.

- To provide a zone of attached gingiva.

For details of surgical technique, the reader is referred to the standard periodontal texts.1–5

To Gain Access for Root Debridement

A number of studies have reported that with crevices less than 4 mm deep, there is little difference in healing following root debridement with direct vision following flap elevation (open debridement), or without direct vision (closed debridement), that is, instrumenting within the periodontal pocket.6–10 Deeper pockets are reported to respond better to open debridement. It is, however, difficult to truly assess the findings of the studies, because as periodontitis is site specific and cyclical in nature11 it is probable that most sites investigated in the clinical studies were free from active disease. In fact, Sokransky et al. (1984)11 found that 95 to 97% of sites were inactive, that is, showing signs of past, but not current, disease activity. Furthermore, Eaton et al., in 1985,12 reported that even with open debridement deposits are not totally removed from the root face, yet healing occurs. Indeed, removal of surface deposits may be all that is required, and vigorous root planing with removal of the root surface may be unnecessary.13 Thus, the clinician has a dilemma as to what type of therapy to prescribe. The fact that re-restoration is required usually resolves this dilemma. The reason for replacement of restorations is often that they are substandard (for example, poor fit, bulbous, poor aesthetics), or associated with caries or mechanical failure. It is necessary to gain access to sound root surface to enable re-fabrication of the restoration.

Pockets Less than 4 mm Deep

Resolution of inflammation usually occurs with a conservative approach without surgery, with the reshaping of existing restorations where appropriate, or the fabrication of well contoured and well fitting temporary or provisional restorations. It is easy to pay lip service to the need for care in the fabrication of these interim restorations, but not achieve good fit and contour. It should be remembered that these are therapeutic restorations and often take more time to make than was originally thought to be necessary (Figs 20-1a–c). Plaque control instruction should be given and tissue response assessed. Crevices less than 3 mm deep should not be instrumented, since loss of attachment ensues from the injury of instrumentation.14 In this context, it is interesting that Glavind, in 1977,15 reported that following surgery, sites with shallow crevices, within the same mouth, that were not professionally cleaned responded just as well as those that were, indicating that patient motivation may be the most important factor. However, detectable hard deposits should be removed and prophylaxis provided. In deeper pockets, root debridement produces a gain of attachment because the effect of instrumentation injury is offset by the reduction of inflammation, resolution and formation of a long junctional epithelium.7 It should be remembered, however, that a gain of attachment of up to 2 mm may not be a real gain, since with resolution of inflammation, the probe tip will no longer penetrate the most apical cells of the dentogingival epithelium.16–17

Fig. 20-1a Inflammation associated with a crown – there was a combination of poor crown margin and a factitious lesion (see Chapter 27). Recession of gingivae on 13 and 23.

Fig. 20-1b Oral hygiene instruction was given and once the factitious nature discovered, the patient was instructed to stop traumatising the tissue (see Chapter 27). Coronally repositioned flaps and connective tissue grafts to cover the roots of teeth 13 and 23 (surgery by Mr J. S. Zamet). Well contoured and well fitting temporary crowns, teeth 11 and 21, with supragingival margins placed for six months. Crowns were cemented for six months with a mix of Tempbond and aureomycin 1% eye ointment, changing the cement monthly. Subsequently, they were cemented with Tempbond.

Fig. 20-1c Final crowns, one year following cementation. Note the slight marginal inflammation that is still present on 11, but is also present on adjacent uncrowned teeth.

Bleeding sites do not necessarily represent active lesions18–21 and may generally be kept under observation for signs of progression before instituting aggressive treatment such as open root debridement. However, where a tooth is being restored and the gingivae are being subjected to the trauma of tooth preparation, retraction and/or subgingival margin placement, the local tissue defences may be adversely affected. Periodic observation is no longer justifiable and the gingivae must be rendered free of any sign of inflammation, notably bleeding. Apart from other considerations, bleeding gingivae can hinder impression taking and cementation procedures, making it difficult to allocate the correct amount of time for the restorative appointment.

Although subgingival irrigation with a variety of agents has failed to control progressive periodontitis,22–24 these agents – 3% hydrogen peroxide in particular – have been reported to have a short-term beneficial effect on gingival bleeding and may be useful adjuncts during the impression taking and cementation stages in patients with less than ideal plaque control, particularly in the early stages of treatment when temporary and provisional restorations are provided. Although administration by the patient using one of the various home irrigation devices may be advantageous, this is true only in the short term, as studies show that the reduction in bleeding is only transient, re-occuring within approximately one month of diminishing.22-24 Hence, with incorrect timing, the restorative procedures may be provided when the beneficial phase has passed.

Pockets Deeper than 4 mm

These are usually treated by conservative means initially, and patient motivation and tissue response assessed. Frequently, gingival shrinkage will occur. If bleeding on probing ceases and there is no further loss of attachment, further treatment will not be required. However, it will be needed if after approximately six months residual pockets greater than 4 mm remain, which bleed on probing,21 particularly four times out of four with four monthly intervals.25 If subgingival margin placement is required aesthetically, provided the patient’s home care is satisfactory, open debridement is performed, in an attempt to produce a rapid result and so enable the restorative phase to be commenced in a predictable environment.26 This is opposed to a longer treatment time and less predictable gingival margin location that results from prolonged closed debridement. If a surgical approach is adopted, conservative techniques, such as the modified Widmen flap, should be used if possible, to conserve gingival tissue.27 Interdental papillae should be retained. Elimination of gingivae and papilae can create unnecessary aesthetic complications.

Apical positioning of the alveolar crest may be required to gain access to caries or root fractures, and this may create such aesthetic complications.

Mechanical debridement without the use of systemic antibiotics is the treatment of choice for patients with chronic adult periodontitis.28–29 Systemic antibiotics are required, however, for the treatment of rapidly progressive periodontitis – loss of ≥ 3 mm on eight or more teeth in at least three quadrants over a period of six months or less – and refractory periodontitis – continued attachment loss after receiving appropriate mechanical debridement.29 If possible, the choice of antibiotic should be made following the use of appropriate culturing techniques. Cultures need only be taken after a lack of response to conventional therapy has been observed.29

The prosthodontist has to be sure that the gingival crest level is stable, particularly in the presence of a high maxillary or low mandibular lip line. In a well maintained patient, such stability usually occurs within six months of surgery.30 Resolution following closed debridement may take much longer, but there are no data on how long one needs to wait using this approach. Open debridement is contraindicated in the presence of poor plaque control.31 Whereas pockets shallower than 4 mm rarely require open debridement (but it may become necessary if bleeding on probing persists in the presence of provisional restorations and good plaque control), the results of scaling and root planing are less certain with pockets deeper than 5 mm.32

The foregoing procedures provide a basis for treatment planning. The criteria for pocket depth should only be regarded as a guide. The difference between bleeding on probing as a sign of progressive periodontitis and as a complication in restorative dentistry, that is, during impression taking and cementation must be understood. Although bleeding is a poor predictor of future disease activity,19–21 the absence of bleeding is rarely associated with progressive periodontitis.19–20 Elimination of bleeding would seem a reasonable objective in the ‘terminal’ periodontitis patient who has, or will require, extensive and expensive restoration and for whom a recurrence of periodontitis would lead to loss of the restorations.

Although studies have reported little difference between various surgical techniques, and reports indicate a genetic ‘memory’ of tissue thickness,33–35 it must be borne in mind that the parameters used for measurement were those used to assess periodontitis. A more recent study18 suggests that most of the sites investigated previously were probably free from disease, and in consequence, the results from the restorative viewpoint must be re-evaluated. Whilst these studies have provided much insight into comparative therapy, their limitation must also be recognized, namely that at the time of investigation the disease might have been quiescent rather than active. The findings of the studies may relate to the effect of different surgical techniques on previously damaged tissue and not to their efficacy in eliminating disease, and may be more indicative of the effect of different plastic surgical techniques in repairing previously damaged tissue. From the restorative viewpoint it is important to know which surgical techniques provide a suitable environment regarding aesthetics, retraction, control of bleeding and long-term marginal stability as well as maintaining a functional periodontal support for the remainder of the patient’s life. Further investigation is indicated.

The clinician must keep an open mind as to the role of surgery and ‘closed’ root debridement in the management of periodontitis, as future studies may dramatically alter the concepts of aetiology, classification and treatment of this disease.

The prescription of maintenance therapy is considered in Chapter 25.

To Eliminate Pockets

To Assist in Removal of Plaque by the Patient

Similar results can be achieved with or without pocket elimination.33 Pocket elimination with regard to disease control would seem to be hard to justify. However, long-term studies are required to enable judgements to be made. The studies of both Morrison et al. and Ramfjord et al., in 1982,36 have gone some way towards demonstrating that with professional debridement at three monthly intervals, teeth with deep pockets can be maintained for long periods without complete pocket elimination, keeping surgical elimination or reduction to ≤ 3 mm. However, results must be interpreted cautiously, since mean data do not assist in the management of individual sites. Furthermore, Claffey et al. (1990)21 reported, that diagnostic predicatability of further attachment loss over a three and a half year period, in patients on a maintenance programme, increased with increasing depth of residual pocketing following initial therapy. Fifty percent of sites with ≥ 7 mm pockets had attachment loss at 42 months. This increased to 67% when associated with bleeding, at 75% of three monthly recall appointments.

The aesthetic consequences of pocket removal must be considered prior to embarking upon surgical procedures (Fig 20-2).

Fig. 20-2 Aesthetic consequences of surgery (courtesy of Mr J. B. Kieser and Butterworth Heinman. Reprinted from Periodontics: A Practical Approach. Butterworth Heinman, 1991).

Fig. 20-2a Start. Note the midline diastema filled with soft tissue.

Fig. 20-2b Post surgery – note the elongated teeth, open embrasures and lack of interdental papillae.

Fig. 20-2c Crowns at cementation. The patient was leaving the country and could not have crowns made in her home country. The porcelain crowns were made in 24 hours, prior to tissue maturation. Note the unaesthetic reverse gingival curve – usually the gingival margin of the canine is apical to that of the lateral incisor. Time constraints did not permit modification of the surgical result to be carried out.

To Treat Furcation Problems

Pockets associated with loss of attachment between the roots of teeth may need to be eliminated by resective or new attachment procedures (see page 429).

To Gain Access to Caries and Sound Root Tissue beyond the Caries

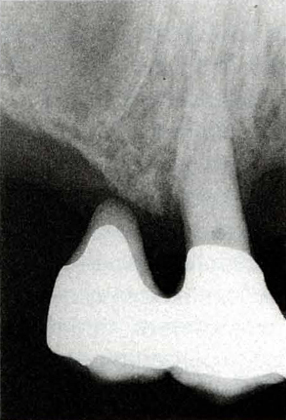

When re-restoring teeth, the removal of pockets is often essential in order to gain access to healthy tooth tissue and obtain a stable gingival margin location (Fig 20-3). Care must be exercised to ensure that unacceptable aesthetics will not result from such treatment.

Fig. 20-3 To gain access to caries and healthy tooth beyond.

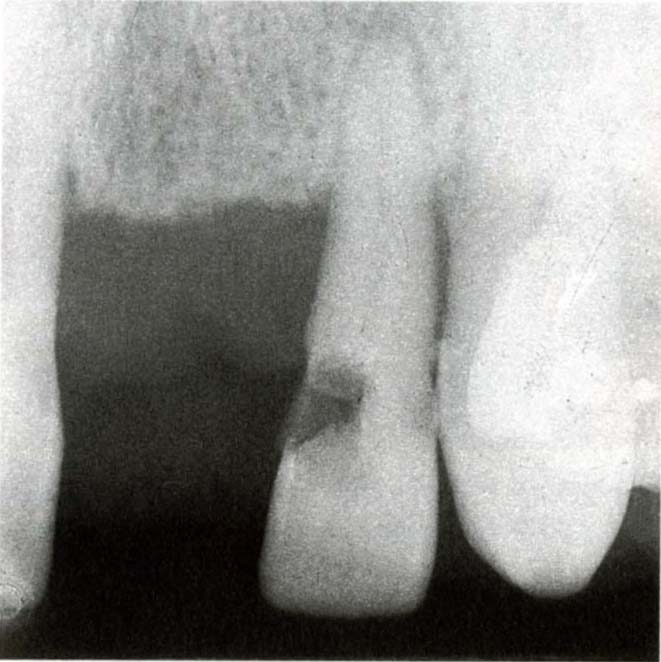

Fig. 20-3a Radiograph showing caries mesially on 11 and 22.

Fig. 20-3b Start.

Fig. 20-3c Crowns six years following cementation. The margin of the crown on 22 has been placed on non-carious dentine but is at the gingival crest following the pocket elimination. Subgingival placement of the crown on 11 is associated with marginal inflammation.

To Gain Access to a Fractured Root

Pocket elimination together will alveolar bone resection may be required. Without orthodontic extrusion (see Chapter 24), aesthetic complications may ensue.

New Attachment Procedures

Studies confirming the efficacy of debridement techniques in achieving bony fill of infrabony defects without the use of bone grafts are discussed by Lindhe 19831 and Kieser 1990.2 The use of call exclusion membranes to achieve new attachment by guided tissue regeneration has been described.37–42 This technique excludes some cells, to allow preferential proliferation of others. It is particularly applicable to the management of Class II furcation involvements and infrabony lesions on one side of a tooth where access is good (Fig 20-4).

Fig. 20-4 New attachment procedure.

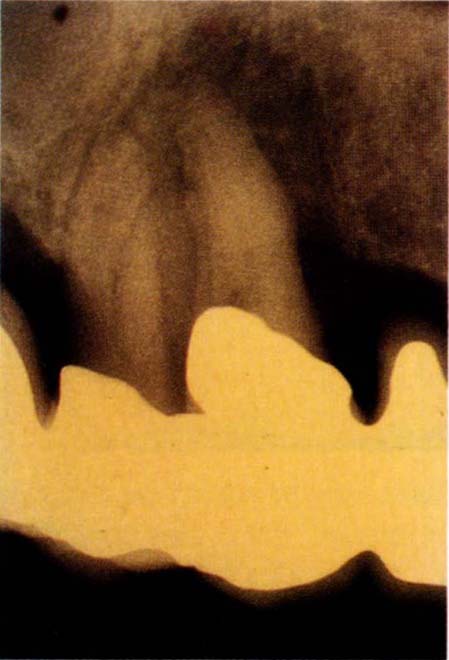

Fig. 20-4a Bone loss associated with the root of 13 and the mesial aspect of 14. There was a 12 mm pocket on the mesial of 14.

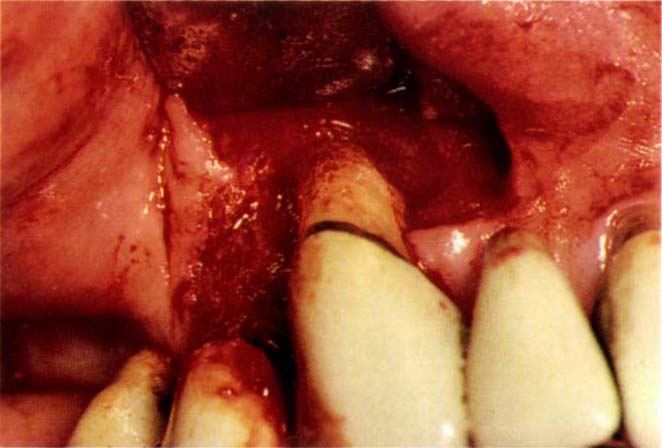

Fig. 20-4b Mucoperiosteal flap raised to expose 13 and 14. Note the incision line, which maintains the papilla between the distal surface of the pontic for tooth 12 and the mesial of tooth 13.

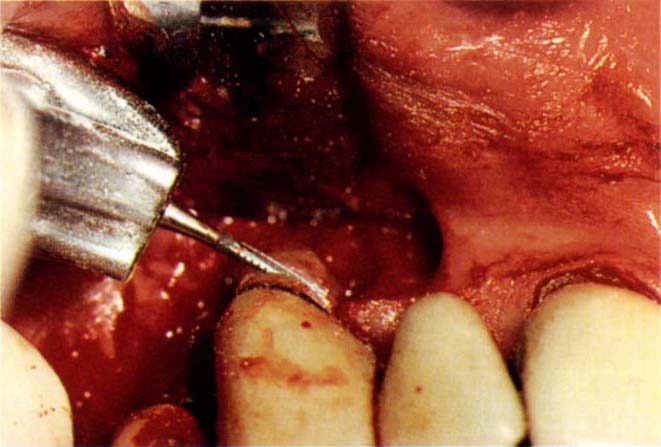

Fig. 20-4c Sectioning the root horizontally with a 557 tungsten carbide bur.

Fig. 20-4d The root is elevated out of the socket and the bone surface curetted.

Fig. 20-4e Note the bone loss to the apex of the mesial and buccal surfaces of tooth 14.

Fig. 20-4f Adapting a Gore-Tex wide single tooth membrane to 14. It was not considered to be necessary to place a membrane over the socket of 13, since the flap could be closed without collapsing and a membrane would have jeopardized 14.

Fig. 20-4g Tissues 24 months after removal of the Gore-Tex. The Gore-Tex was removed at 6 months. The crevice of 14 could be probed only to 2 mm. Note the tissue/pontic relationship of teeth 12 and 13.

Fig. 20-4h Radiograph showing bone on the mesial of 14 – 2 years after treatment.

The Use of Guided Tissue Regeneration Techniques may be Considered in the Following Circumstances

- Good plaque control.

- Attachment loss of more than 4 mm. Anything less can be effectively treated using more conventional techniques.

- Class II furcation involvement. Improvement, and sometimes elimination may be possible with Class III furcation involvements.

- Distance from cemento-enamel junction or crown margin to furcation more than 2 mm.

- Vital or successfully root treated tooth.

- Sufficient attached gingivae to cover the cell exclusion membrane. Gingival recession may make this difficult.

- Adequate surgical access.

- Appropriate medical history. The technique is not recommended in patients with endocardial lesions, uncontrolled diabetes or deficient immune systems.

- Localized lesions.

- Infrabony defect on a single accessable root surface.

- Cooperative patient, able to meet the necessary attendance demands.

- Clinician attended recognized courses.

- Careful surgical technique which is demanding allows little room for error and is dependent on meticulous root and defect debridement, precise membrane placement and suturing.

The Technique should not Generally be Used in the Following Circumstances

- Absence of any of the above.

- Extremely extensive lesions with little or no intact periodontium.

- Defects precluding the provision of adequate space for the membrane, such as horizontal defects.

- The occurrence of flap perforations or compromised flap preparations during surgery.

- Multiple tooth procedures in which more than two adjacent pieces of membrane need to be implanted.

Serious consideration must be given to the use of guided tissue regeneration whenever localized periodontitis jepordises existing restorations (Fig 20-4), or when re-restoration is required. Resorbable membranes, for example, Vicryl, which eliminate the need for the second stage of surgery to remove them, are becoming available. The rate of resorption must, however, match the rate of bone deposition, this makes these membranes unpredictable in their efficacy.43–44 If the removal of a resorbable membrane becomes necessary, its partially desintegrated state may make this very difficult.

To Lengthen the Height of the Clinical Crown (Figure 20-5)

Patients with failed restorations and/or wear of remaining teeth, will frequently require clinical crown lengthening surgery preparatory to definitive restoration. Such patients often have:

- Short clinical crowns.

- Thick firm gingivae.

- Minimal crevice depths.

- Resistance to periodontitis.

- Thick dense bone.

- Poorly contoured restorations (Fig 20-5e).

- Localized gingival inflammation, particularly associated with poorly contoured restorations.

- Fractured restorations and/or teeth.

- Uncemented restorations.

- Wear, such that the pulp is exposed or is visible in outline.

- Absence of tooth mobility.

- Poor aesthetics, particularly if porcelain has been used on occlusal surfaces.

- Loss of vertical dimension, often lessened to some extent by ‘compensatory’ mechanisms describ/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses