Chapter 2

Infective Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a microbial infection of the endothelial surface of the heart or heart valves that most often occurs in proximity to congenital or acquired cardiac defects.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Previously, IE was classified as acute or subacute, to reflect the rapidity of onset and duration of symptoms before diagnosis; however, this classification was found to be somewhat arbitrary. It has now largely been replaced by a classification that is based on the causative microorganism (e.g., streptococcal endocarditis, staphylococcal endocarditis, candidal endocarditis) and the type of valve that is infected (e.g., native valve endocarditis [NVE], prosthetic valve endocarditis [PVE]). IE also is classified according to the source of infection—that is, whether it is community-acquired or hospital-acquired—or whether the patient is an intravenous drug user (IVDU).

IE is a disease of significant morbidity and mortality that is difficult to treat; therefore, emphasis has long been directed toward prevention. Historically, various dental procedures have been reported to be a significant cause of IE, because bacterial species found in the mouth frequently have been found to be the causative agent. Furthermore, whenever a patient is given a diagnosis of IE caused by oral flora, dental procedures performed at any point within the previous several months typically have been blamed for the infection. As a result, antibiotics have been administered before certain invasive dental procedures in an attempt to prevent infection. Of note, however, the effectiveness of such prophylaxis in humans has never been substantiated, and accumulating evidence more and more questions the validity of this practice.

Epidemiology

IE is a serious, life-threatening disease that affects more than 15,000 patients each year in the United States; the overall mortality rate approaches 40%.

When populations at enhanced risk are considered, the incidence rate is increased. One study reported the lifetime risk of acquiring IE with various conditions.

TABLE 2-1 Lifetime Risk of Acquiring Infective Endocarditis

| Predisposing Condition/Factor | No. of Patients/100,000 Patient-Years |

|---|---|

| General population | 5 |

| Mitral valve prolapse without audible cardiac murmur | 4.6 |

| Mitral valve prolapse with audible murmur of mitral regurgitation | 52 |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 380-440 |

| Mechanical or bioprosthetic valve | 308-383 |

| Cardiac valve replacement surgery for native valve | 630 |

| Previous endocarditis | 740 |

| Prosthetic valve replacement in patients with PVE | 2160 |

PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Data from Steckelberg JM, Wilson WR: Risk factors for infective endocarditis, Infect Dis Clin North Am 7:9-19, 1993.

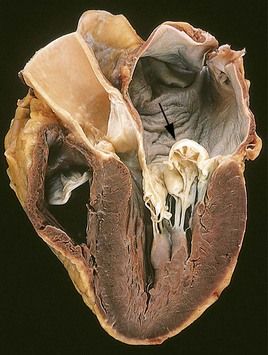

FIGURE 2-1 Mitral stenosis with diffuse fibrous thickening and distortion of the valve leaflets in chronic rheumatic heart disease.

(From Schoen FJ, Mitchell RN: The heart. In Kumar V, et al, editors: Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

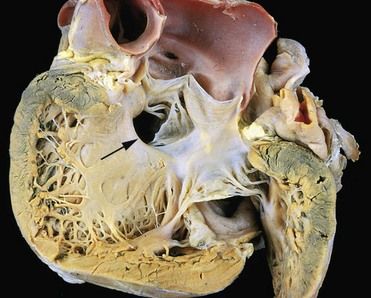

FIGURE 2-2 Prolapse of the posterior mitral valve leaflet into the left atrium.

(Courtesy William D. Edwards, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. From Schoen FJ, Mitchell RN: The heart. In Kumar V, et al, editors: Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

FIGURE 2-3 Calcific aortic stenosis of a previously normal valve. Nodular masses of calcium are heaped up within the sinuses of Valsalva.

(From Schoen FJ, Mitchell RN: The heart. In Kumar V, et al, editors: Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

FIGURE 2-4 Gross photograph of a ventricular septal defect (defect denoted by arrow).

(Courtesy William D. Edwards, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. From Schoen FJ, Mitchell RN: The heart. In Kumar V, et al, editors: Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

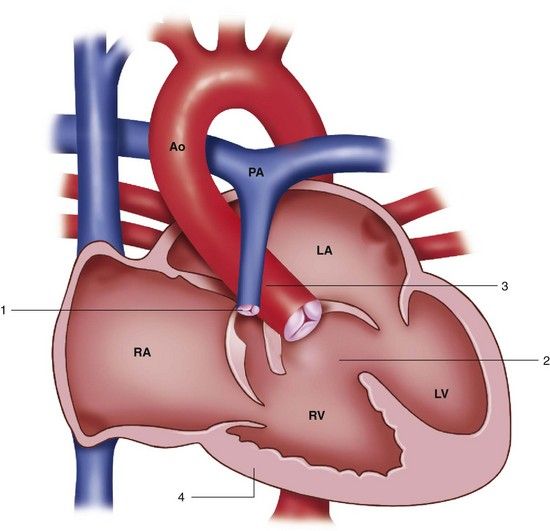

FIGURE 2-5 Tetralogy of Fallot. 1, Pulmonary stenosis. 2, Ventricular septal defect. 3, Overriding aorta. 4, Right ventricular hypertrophy. Ao, Aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

(Redrawn from Mullins CE, Mayer DC: Congenital heart disease: a diagrammatic atlas, New York, 1988, Wiley-Liss.)

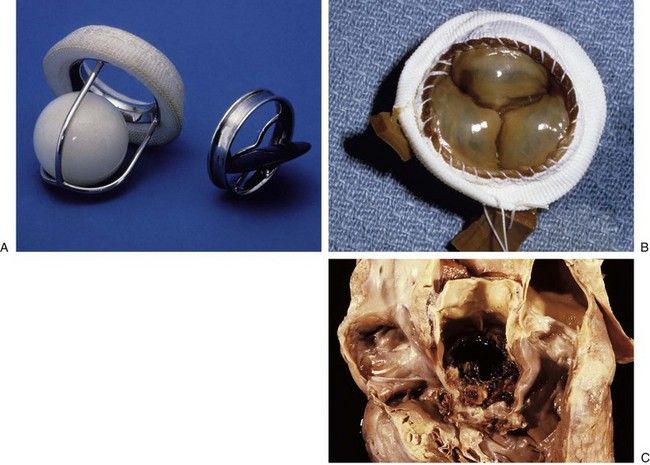

FIGURE 2-6 Prosthetic cardiac valves.

A, Starr-Edwards caged ball mechanical valve. B, Hancock porcine bioprosthetic valve. C, Prosthetic valve endocarditis.

TABLE 2-2 Predisposing Conditions Associated with Infective Endocarditis (IE)

| Underlying Condition | Frequency of IE |

|---|---|

| Mitral valve prolapse | 25-30% |

| Aortic valve disease | 12-30% |

| Congenital heart disease | 10-20% |

| Prosthetic valve | 10-30% |

| Intravenous drug abuse | 5-20% |

| No identifiable condition | 25-47% |

The incidence of IE among IVDUs ranges from 150 to 2000 per 100,000 person-years.

Etiology

About 90% of community-acquired cases of native valve IE are due to streptococci, staphylococci, or enterococci, with streptococci being the most common causative organisms.

Staphylococci are the cause of at least 30% to 40% of cases of IE; of these, 80% to 90% are due to coagulase-positive S. aureus.

Other microbial agents that less commonly cause IE include the HACEK group (Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum, Listeria monocytogenes, Bacteroides fragilis, and fungi.

Pathophysiology and Complications

Although the precise mechanism whereby IE occurs has not been fully elucidated, it is thought to be the result of a series of complex interactions of several factors involving endothelium, bacteria, and the host immune response. The sequence of events leading to infection usually begins with injury or damage to an endothelial surface, most often of a cardiac valve leaflet. Although IE can occur on normal endothelium, most cases begin with a damaged surface, usually in proximity to an anatomic defect or prosthesis. Endothelial damage can result from any of a variety of events, including the following

• Directed flow from a high-velocity jet onto the endothelium

Fibrin and platelets then adhere to the roughened endothelial surface, where they form small clusters or masses, resulting in a condition called nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) (

FIGURE 2-7 Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE).

(From Schoen FJ, Mitchell RN: The heart. In Kumar V, et al, editors: Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

FIGURE 2-8 Viridans streptococcal endocarditis of mitral valve.

(Courtesy W. O’Conner, MD, Lexington, Kentucky.)

The clinical outcome of IE depends on several factors, including

• Local destructive effects of intracardiac (valvular) lesions

• Embolization of vegetative fragments to distant sites, resulting in infarction or infection

• Hematogenous seeding of remote sites during continuous bacteremia

• Antibody response to the infecting organism, with subsequent tissue injury caused by deposition of pre-formed immune complexes or antibody-complement interaction with antigens deposited in tissues

Although combination antibiotic and surgical treatment is effective for many patients, complications are common and serious. The most common complication of IE, and the leading cause of death, is heart failure, which results from severe valvular dysfunction. This pathologic process most commonly begins as a problem with aortic valve involvement, followed by mitral and then tricuspid valve infection. Embolization of vegetation fragments often leads to further complications such as stroke. Myocardial infarction can occur as the result of embolism of the coronary arteries, and distal emboli can produce peripheral metastatic abscesses. Pulmonary emboli, usually septic in nature, occur in 66% to 75% of IVDUs who have tricuspid valve endocarditis.

Signs and Symptoms

The classic findings in IE include fever, heart murmur, and positive blood culture, although the clinical presentation may vary. Of particular significance is that the interval between the presumed initiating bacteremia and the onset of symptoms of IE is estimated to be less than 2 weeks in more than 80% of patients with IE.

Fever, the most common sign of IE, occurs in up to 80% to 95% of patients.

FIGURE 2-9 Petechiae in infective endocarditis.

(From Fowler VG Jr, Bayer AS: Infective endocarditis. In Goldman L, Ausiello D, editors: Cecil medicine, ed 23, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

FIGURE 2-10 Osler’s node in infective endocarditis.

(From Fowler VG Jr, Bayer AS: Infective endocarditis. In Goldman L, Ausiello D, editors: Cecil medicine, ed 23, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

FIGURE 2-11 Splinter hemorrhages of the nail beds in infective endocarditis.

(From Porter SR, et al: Medicine and surgery for dentistry, ed 2, London, 1999, Churchill Livingstone.)

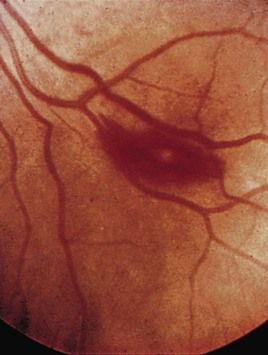

FIGURE 2-12 A Roth spot in the retina in infective endocarditis.

(From Forbes CD, Jackson WF: Color atlas and text of clinical medicine, ed 3, Edinburgh, 2003, Mosby.)

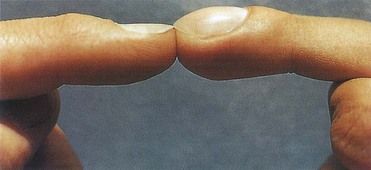

FIGURE 2-13 Nail clubbing may appear within a few weeks of development of IE.

(From Zipes DP, et al, editors: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

The diagnosis of IE should be considered for a patient with fever along with one or more of the following cardinal elements of IE: a predisposing cardiac lesion or behavior pattern, bacteremia, embolic phenomena, and evidence of an active endocardial process.

Major criteria are two of the aforementioned cardinal elements:

• Evidence of endocardial involvement (e.g., positive findings on echocardiography, presence of new valvular regurgitation)

Minor criteria include the following factors:

Definitive diagnosis of IE requires the presence of two major criteria, one major and three minor criteria, or five minor criteria.

Laboratory Findings

Other than blood culturing, laboratory tests used for the diagnosis and treatment of IE are basic and nonspecific and may include a complete blood count with differential, electrolyte panel, renal function tests, urinalysis, plain chest radiograph, and electrocardiogram (ECG).

Echocardiography, transthoracic or transesophageal, is used to confirm the presence of vegetation in patients suspected of having IE; it has become a cornerstone in the diagnostic process. Echocardiographic evidence of vegetation is one of the major findings included in the Duke criteria.

Medical Management

Before the advent of antibiotics, IE almost always was fatal. This poor outcome has changed dramatically with early diagnosis and the institution of antibiotic therapy or surgical treatment, or both. Although the survival rate has greatly improved, the overall mortality rate still hovers around 40%.

Recently, guidelines for the diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of infective endocarditis have been revised as an American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Statement.

Patients with endocarditis arising as a complication after surgery to place prosthetic valves or other prosthetic material that is caused by a highly penicillin-susceptible strain (MIC of 0.12 µg/mL or less) should receive 6 weeks of therapy with penicillin or ceftriaxone, with or without gentamicin for the first 2 weeks. Those with endocarditis caused by a strain that is relatively or highly resistant to penicillin (MIC greater than 0.12 µg/mL) should receive 6 weeks of therapy with penicillin or ceftriaxone combined with gentamicin. Vancomycin therapy is recommended only for patients who are unable to tolerate penicillin or ceftriaxone.

Regardless of whether IE is community- or hospital-acquired, most S. aureus organisms produce β-lactamase; therefore, the condition is highly resistant to penicillin G. The drug of choice for treatment of IE caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) is one of the semisynthetic, penicillinase-resistant penicillins such as nafcillin or oxacillin sodium. For patients with native valve S. aureus endocarditis, a 6-week course of oxacillin or nafcillin with the optional addition of gentamicin for 3 to 5 days is recommended. Staphylococcal PVE is treated as for NVE, except that treatment is given for a longer period. For strains resistant to oxacillin, vancomycin is combined with rifampin and gentamicin.

Surgical intervention may be necessary to facilitate a cure for IE or to repair damage caused by the infection. Indications for surgery include moderate to severe heart failure caused by valvular dysfunction, unstable or obstructed prosthesis, infection uncontrollable by antibiotics alone, fungal endocarditis, and intracardiac complications with PVE.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses