Chapter 2

Indications for Crowns

Aim

To consider and review the indications for indirect full and partial coverage crowns.

Outcome

On reading this chapter the reader will appreciate the indications for crowns. The use of clinical examples helps the reader understand the complexities of the decision making process.

Introduction

The demand for crowns remains high. The development of new materials has, to some extent, reduced the need for full coverage restorations, but crowns will remain an important element of prosthodontics for decades to come. Crowns have various cost consequences, including the removal of large amounts of remaining tooth tissue. As a consequence the indications for crown placement need to be carefully considered. These indications are not definitive, remain largely subjective and typically have to be applied on a case by case assessment.

The indications for crowns are:

-

replacement crowns

-

protection of root-filled teeth

-

broken down and worn teeth

-

unsightly dental appearance

-

cracked teeth

-

realignment of occlusal plane.

Replacement Crowns

The most common indication for placing a crown in today’s practice is the failure and replacement of an existing crown. On average crowns last 10 years, but under certain circumstances may remain in clinical service for 15–20 years. Various factors influence the longevity of crowns. These include caries, periodontal disease, loss of vitality, mechanical failure and changes to adjacent teeth with increasing age. The development of caries adjacent to the junction between tooth and crown remains one of the most common reasons for replacement, in particular, in older patients. Despite being a largely preventable disease as discussed in Chapter 1, caries remains the principle reason for both initial and replacement operative dentistry.

Apart from caries, mechanical and aesthetic failures are common indications for replacement crowns. Structural failure is a very obvious indication for replacement (Fig 2-1). Since porcelain is a brittle material, fractures are not uncommon, in particularly when the occlusal forces are high. This can be seen when opposing teeth contact the metal and porcelain junction on lateral and anterior guidance. The occlusal forces impact on this junction creating stress, which ultimately leads to fracture.

Fig 2-1 A common reason for the replacement of crowns is mechanical failure.

Another indication for replacement is an aesthetic failure. This may be clinical or laboratory failure or a consequence of the aging dentition. Bright or opaque crowns can be a result of insufficient depth reduction during crown preparation. Metal-ceramic crowns need 1.5–1.75 mm buccal reduction to provide sufficient space for the metal and porcelain. If this space is not provided opaque core porcelains used to hide the metal substructure make the crown appear bright or have a high value (Fig 2-2).

Fig 2-2 The two central incisors have a dull appearance and lack the natural translucency of teeth. The reason is that the preparation of the tooth created insufficient space for the metal and porcelain. There is insufficient space available for the aesthetic porcelains which are needed to hide the opaque inner ceramic core.

The problem with replacement crowns is that removal of caries and re-positioning of the gingival margin substantially reduces the amount of remaining tooth tissue. As the gingival margin migrates apically, the crown to root ratio is reduced and the clinical crown height is increased. Ideally, the width of the crown should be 0.75 to 0.85 of its length. Increasing the length beyond this ratio detracts from the aesthetic outcome giving what is commonly termed “tombstones” (Fig 2-3). Also as tooth length increases “black triangles” develop interdentally, compromising the dental appearance.

Fig 2-3 The appearance of long clinical crowns is difficult to mask. Once the length to width ratio exceeds 0.75–0.8 the appearance of the crowns is compromised. Replacement crowns are needed for this patient who already has long teeth. Increasing their length even further will accentuate the crown’s height/width ratio and emphasise the black triangles between the teeth.

Long clinical crowns create a number of practical difficulties, not the least of which is tooth preparation. Avoiding undercuts on long preparations, let alone pulpal exposure, is difficult and can be avoided either by carefully controlling the taper of the preparation or by finishing the margin supragingivally. The latter has the disadvantage that a margin is visible above the gingival tissues and may be contraindicated in patients with a high lip line. Long clinical crowns can also appear unattractive.

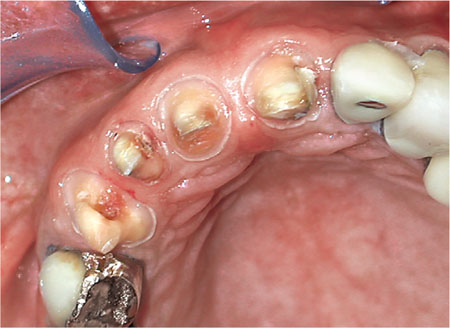

Perhaps the most challenging clinical conundrum when replacing a crown is the position of the gingival margin. Subgingival margins create difficulties both in terms of recording an accurate impression and because patients have difficulty keeping the area plaque free (Fig 2-4). Both may increase the risk of developing caries and periodontal disease along the margin. A common clinical dilemma is whether a crown is appropriate for an extensively restored tooth with a plastic restoration below the gingival margin. Placing expensive restorations on teeth with doubtful prognosis may lead to early failure. On the other hand weakened cusps are liable to fracture. With the increasing cost of materials and laboratory charges, the expectation of patients is that crowns should have a reasonable longevity, of around 10 years. If an accurate impression cannot be taken to ensure a good fit between crown and tooth the use of a crown to restore the tooth should be questioned. In some cases, however, a pragmatic approach can be justified provided the patient is fully informed of the alternatives and risks.

Fig 2-4 The removal of the existing crown and caries has produced a deep subgingival distal margin. The decision as to whether the tooth justifies a crown is dependant on whether or not an accurate impression can be recorded along this margin. Crown lengthening would provide better access to the distal margin but will increase the cost.

The other problem with replacement crowns is that the state of the underlying core is typically unknown prior to removal of the old crown. The core supporting the crown should have a near parallel taper approaching 15° with a form to maximise the retention and support of the crown. The collar of tooth remaining should be a minimum of 2 mm in height with near parallel preparation and a form which largely mirrors the anticipated shape of the crown. Once the old crown is removed it is not uncommon to find that the shape of the existing tooth preparation is far from ideal and not suited for its intended purpose (Fig 2-5). Removal of diseased dentine can further reduce the retention of a core and crown, leaving a choice between either electively root filling the tooth to gain additional retention or by relying on an adhesive luting cement.

Fig 2-5 Replacement crowns on extensively restored upper anterior teeth. The teeth have had recurrent caries removed leaving preparations which are not ideal in shape for new crowns.

Endodontically Treated Teeth

Not all root-filled teeth require an indirect coronal restoration. There is relatively little guidance in the literature as to which teeth require a crown following root treatment, as most research has been undertaken on extracted teeth. Traditional thinking is that root treated teeth are liable to fracture and therefore require occlusal coverage for protection. But this is not necessarily the case. A good guide is if the surface area of the access cavity exceeds one third of the occlusal surface of the tooth then a crown or onlay with cuspal coverage i/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses