Chapter 19

Problem Solving in the Management of Tooth Fractures and Traumatic Tooth Injuries

Problem-solving issues and challenges in the management of traumatic tooth injuries addressed in this chapter are:

“When a Tooth is loosened by violence, but not moved out its socket, ligature alone, and astringent washes to brace the gums, are sufficient for the cure. In this case the pain ceases with the looseness of the Teeth; but if it be violent in the beginning, sedatives must be applied.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Tooth Crazes, Cracks, and Fractures

The diagnosis and management of structural defects in teeth other than those caused by accidental trauma pose a unique challenge for the clinician. These defects involve posterior teeth and are usually slow to develop and manifest themselves within a variety of intertwined variables. They can be on the surface and stable, or they can migrate into the tooth, resulting in significant structural defects and clinical challenges. All defects may involve the crown, root, or both, in addition to being horizontal, vertical, or angulated.

The types of alterations in tooth structure include crazes, cracks, and fractures. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of these alterations is dependent on thorough patient assessment, identification of those factors that contribute to these defects, management of those factors when possible by the clinician, and creative measures in the overall prevention of these problems. Fractures that are the result of accidental trauma and that occur primarily in the anterior teeth are addressed in the next section of this chapter.

For purposes of clarification and clinical differentiation, the following descriptions are provided. Crazes are areas of weakness in the tooth structure where further propagation may result in a crack or facture. These are not visible radiographically but can be seen with fiberoptic transillumination. Cracks are definite breaks in the continuity of the tooth structure beginning in the enamel or cementum. No separation is evident clinically, and these are visible with fiberoptic transillumination in which light transmission is impeded across the crack line. They may often be stained due to patient diet. Fractures exhibit definite separation of the tooth structure into two or more distinct segments and are visible clinically and sometimes radiographically. They also may exhibit stain when located coronally.

Many factors that predispose to these tooth defects cannot be altered or controlled by the clinician. These include masticatory accidents, bruxism, and thermal cycling.

There is a paucity of new information regarding these types of tooth defects, and therefore the reader is referred to previous editions of this text and other supportive references that will detail the challenges of the clinician faces with these types of problems.

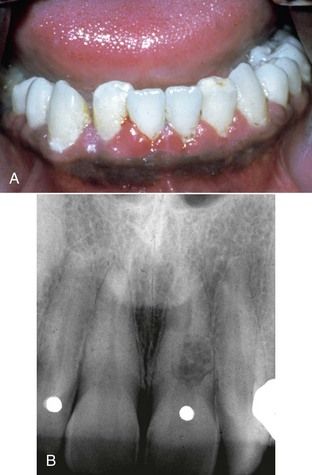

FIGURE 19-1 A, Mandibular molar with crack lines on the mesial and marginal ridges (arrows). B, Mandibular molar with a crack running parallel to the buccal developmental groove (arrows).

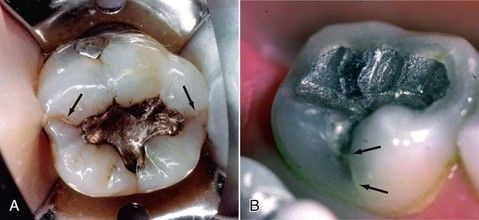

FIGURE 19-2 A, Image shows a symptomatic molar that was excavated and stained with methylene blue on the cavity floor. Note the mesial-to-distal fracture. B, Evidence of a fracture on the distal marginal ridge often results from weakened tooth structure in that area. C, Extracted tooth shows the crack (arrows) running apically down the root in a diagonal manner. Also the periodontal ligament forms a tract as the crack is propagated. Note the lack of divergence in the occlusal preparation that is necessary for seating inlays. This was probably the contributing factor in this tooth’s demise. D, After access opening, the distal fracture line can be seen to run down the distal wall. The tooth was extracted.

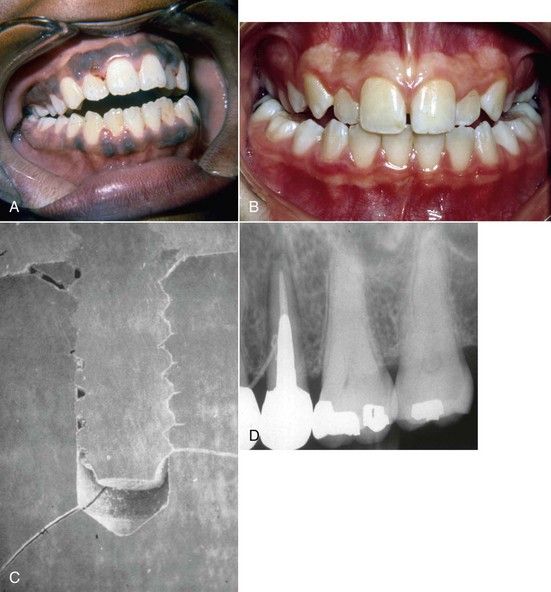

FIGURE 19-3 Open anterior bites (A) and cross bites (B) contribute to excessive occlusal forces on the posterior teeth. C, Placement of multiple pins in a tooth for retention may lead to fractures. Note the fractures at the base of this pin (scanning electron microscopy photo). D, Traceable sinus tract to the midroot of this premolar. Note the size and shape of the intraradicular post. The tooth was fractured vertically.

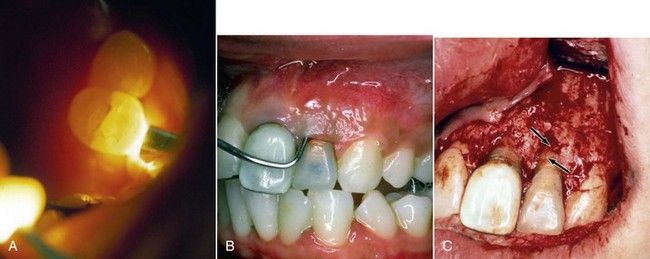

FIGURE 19-4 A, Placement of a fiberoptic on a symptomatic maxillary premolar. Note that the light does not pass the fracture line. Transillumination can be more dramatic without the overhead light. B, Clinically deep probing in a narrow channel. C, Tissue reflection allows for visualization of the fracture (arrows).

FIGURE 19-5 Proximal view of the extracted tooth; note the oblique fracture line. Clinical view in

Traumatic Tooth Injuries

The management of traumatic injuries is a constant source of difficulty for the clinician because of the complexity in diagnosing and treating these injuries properly.

The first and most important step in understanding how to treat these injuries is to determine the nature of trauma.

Active prevention of coronal fractures in normal day-to-day living is unrealistic and a moot point. Prevention during hazardous activities such as job-related activities (e.g., during sports), however, may occur in the form of mouth protection and on-the-job training to avoid circumstances that may predispose to traumatic incidents.

In cases in which an acute trauma accident has resulted in a crown fracture (

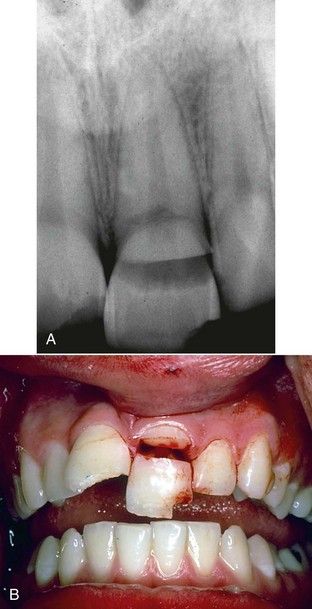

FIGURE 19-6 Enamel-dentin fractures, with the right central incisor having an angled fracture into the coronal portion of the root.

FIGURE 19-7 A, Complicated coronal fractures that are deep into the dentin with an exposed pulp. B, Clinical view.

FIGURE 19-8 Complete coronal fracture that lends itself to immediate and complete root canal treatment and appropriate restorative procedures. However, because the patient is young, a prefabricated metallic post may not be indicated, but rather a bonded type of carbon fiber post may be better.

Luxation injuries present a greater demand for the clinician in their management, as they must be diagnosed accurately.

Concussion

A concussion injury is defined as a relatively minor blow to the tooth in which the affected tooth is not damaged, but the periodontium becomes inflamed. Typically, patients experience mastication sensitivity or pain on brushing or pressure on the tooth. No splinting is required in these types of luxation, and only palliative treatment is required. In most instances, reducing the occlusion is all that is required. Patients should be reevaluated within the first 2 weeks after the injury to ensure that no further treatment is required. In the vast majority of cases, root canal therapy is not indicated, because only a small percentage of these injuries become necrotic. Monitoring pulpal status for 1 year is recommended (

Subluxation

A subluxation is slightly more severe than a concussion of the tooth, because increased mobility exists that is comparable with a periodontally involved tooth (mobility +1 to +2).

Reduction of the occlusal forces on the tooth will aid in the healing process and minimize the patient’s symptoms. Subluxations account for the most frequent type of luxation injury, although the probability of pulpal necrosis zis very small with subluxation injuries.

Extrusive Luxation

In extrusive luxation injuries, the tooth is dislocated along its long axis and can be displaced almost entirely out of the socket (

FIGURE 19-11 An extrusively luxated central incisor. Note that the tooth is dislocated along its long axis.

Initially the soft-tissue damage must be assessed and managed properly. The tooth is carefully and accurately repositioned in the socket. This procedure may be performed manually with gauze or with forceps (if significant dislocation has occurred) to replace the tooth gently into its original position. Keep in mind that teeth will usually realign into their original position in the socket without significant forces being required. However, the greater the post-trauma time period before treatment, the higher the likelihood of coagulation in the socket; therefore additional force may be required to accomplish the repositioning.

Sensibility testing is used initially, with variable or no responses expected, and again on reexamination to determine the pulpal status. This is especially important in teeth with immature root formation. If there is no response in the tooth with a fully formed apex, necrosis can be assumed to have occurred.

In extrusive luxation injuries, the neurovascular bundle is usually disrupted, and therefore the blood supply is lost to the tooth. In adult patients and in young patients with closed apices, the likelihood of revascularization is extremely low and should not be considered a likely consequence of the healing process. Because the majority of these cases become necrotic, the patient should be notified that a root canal procedure will be necessary within a couple of weeks of the trauma or earlier at the time of splint removal. In all cases of extrusive luxation injuries, the teeth must be splinted.

All luxation injuries require splints, using one nontraumatized tooth on either side of the traumatized tooth. For example, if only one tooth is luxated, then one healthy tooth on either side of the traumatized tooth should be included in the splint. If two teeth are luxated, then a total of six teeth should be included in the splint (two teeth on either side of the two teeth that are traumatized for a total of six). The type of splint (physiologic, rigid, or passive) is inconsequential to the healing process. However, in most instances, a nonrigid splint is easier to place and will avoid the possibility of exerting excessive pressure on the damaged periodontal ligament.

The splint should be placed for up to 2 weeks. During this period, the periodontium will stabilize the tooth sufficiently, and minor to normal mobility will be noted following splint removal. Should the tooth be excessively mobile compared with a nontraumatized contralateral tooth, the splint may remain in place until normal mobility is noted. The use of a physiologic passive or flexible splint is indicated for any type of luxation injury.

Lateral Luxation

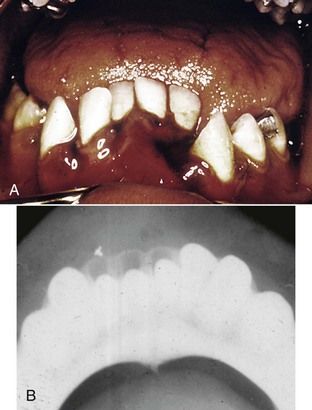

Lateral luxation injuries are defined as a dislocation of the tooth in a mesial, distal, facial, or lingual (palatal) direction, with comminution or fracture of the bony alveolar socket. It is rare for a patient to have a pure lateral luxation. Most cases will have both a lateral and an extrusive component (

FIGURE 19-12 A, Lateral luxation injury. Note the lateral and extrusive component to the injury. B, Significant lateral extrusion of the mandibular incisors. Note the radiographic view and the movement in the alveolar socket.

The assessment phase is similar to that for extrusive injuries. In these instances, a blunt instrument should be inserted gently into the alveolar socket to move the fractured bony segment back to its original position before the tooth can be properly repositioned.

Because of the nature of the damage with lateral luxation injuries, the probability of pulpal damage and subsequent endodontic therapy is high.

Intrusive Luxation

Intrusive luxation injuries are the most severe type of luxation injury and therefore have the poorest prognosis.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses