Chapter 17

Statistical Data

The content of this chapter serves to support the various topics covered in the preceding chapters and to present statistical data in a compact and easily accessible format.

The data in this chapter have been selected and compiled from results of studies carried out mainly in Western countries. The data presentation starts with the formation, eruption, and emergence of the deciduous teeth, followed by that of the permanent teeth. The correlations in crown widths among individual teeth in both dentitions and between the deciduous teeth and their successors are presented. Dental arch dimensions, the size of the overjet and overbite, and molar occlusion are shown from 3 to 18 years of age in tables and graphs. Information on the variation in inclination and angulation of teeth in adults is provided. Finally, the prevalence of agenesis and malocclusions is given.

A comparison of findings from various published studies is complicated by differences in design, data collection, and presentation of results.1 For example, most information on times of emergence of deciduous teeth is derived from observations in clinics for babies and small children and from notes made by mothers.2 The data collected in this way are more precise than those derived from annually prepared dental casts. Dental casts have served to provide information not only on times of emergence of permanent teeth but also on changes in dental arch dimensions and occlusion. In some studies, only children with normal occlusion were included. In other studies, this selection criterion was not or only moderately used.

Annually collected data on times of emergence are based on observations that certain teeth had emerged in the preceding 12 months. Assuming a normal distribution of times of emergence, the calculated average times of emergence should be decreased by 6 months. However, this was not done in any of the studies that dealt with times of emergence. As a result, the data presented in this chapter can be assumed to be 6 months higher than in reality. There is only one investigation in which data were collected every 6 months—the Nijmegen Growth Study. Therefore, the data on times of emergence derived from that study are 3 months too high.

The most valuable information is obtained with longitudinal growth studies, followed by those with overlapping cohorts (mixed longitudinal). Sometimes it is more practical to collect data only once from a very large sample (cross-sectional). The data presented in this chapter come from all three types of studies.

Formation and Emergence of Deciduous Teeth

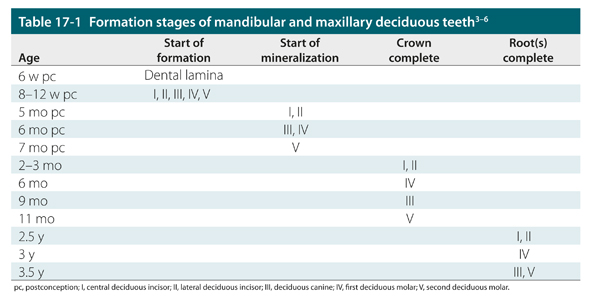

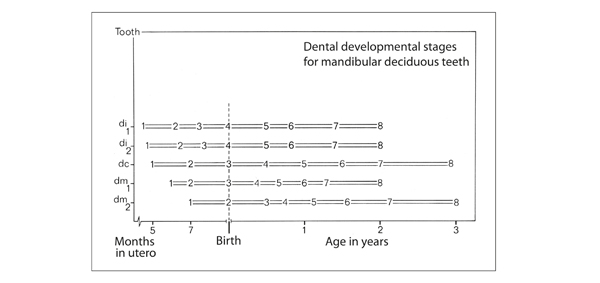

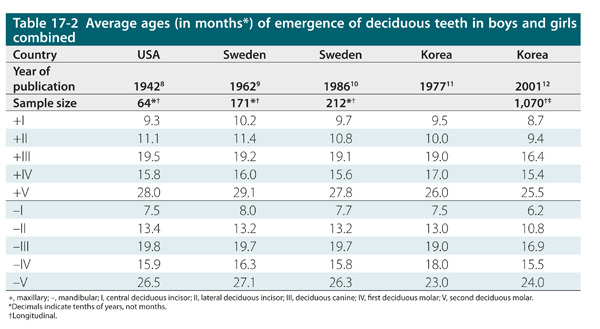

The progress in formation of deciduous teeth is plotted against age in Table 17-1 and for the mandibular deciduous teeth in Fig 17-1. The average times of emergence of deciduous teeth in five populations are presented in Table 17-2. The results of the longitudinal studies differ only slightly from each other but deviate from those of the cross-sectional study. From the data in Table 17-2, it could be concluded that the average sequence of emergence is the same in all five studies. However, this presentation disguises the large individual variation in time of emergence. In the longitudinal study of 171 children, only 5% had the average sequence in time of emergence.4

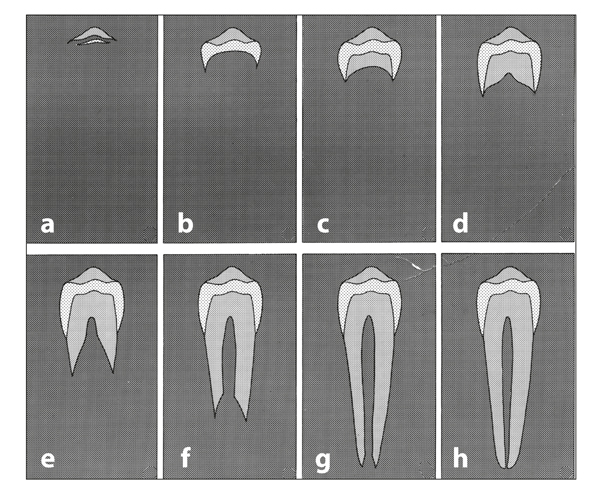

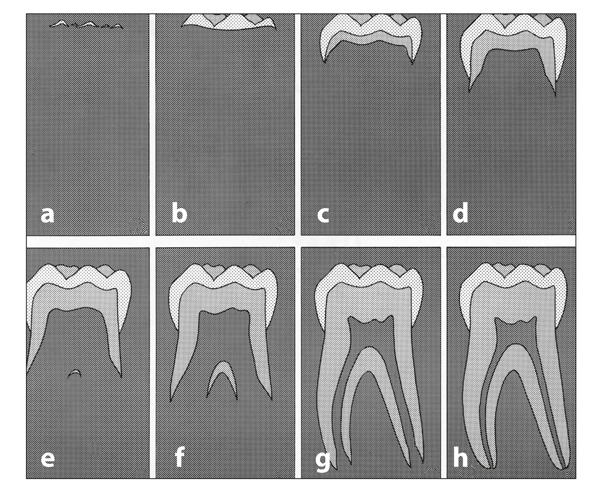

Fig 17-1 The eight formation stages (see Figs 17-3 and 17-4) of mandibular deciduous teeth plotted against age.7 di1, central deciduous incisors; di2, lateral deciduous incisors; dc, deciduous canines; dm1, first deciduous molars; dm2, second deciduous molars.

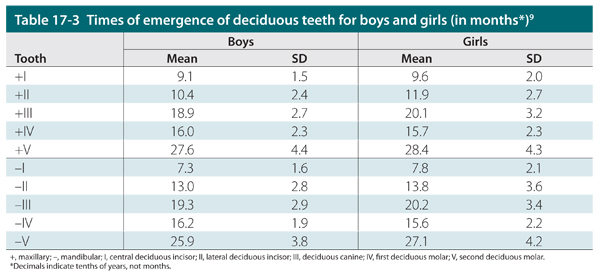

The average times of emergence of deciduous teeth differ between boys and girls, but the average sequence of emergence does not (Table 17-3; Fig 17-2). In accordance with the large individual variation in time of emergence of deciduous teeth, the standard deviation (SD) in times of emergence is high. The range in time of emergence is the smallest for the central incisors (SD, 1.8 months), larger for the lateral incisors and canines (SD, 2.9 months), and the largest for the second molars (SD, 4.2 months). It is remarkable that, in contrast with the permanent teeth, deciduous teeth emerge in boys earlier than in girls, with the exception of the first molars. Another difference between the two dentitions is that the maxillary deciduous teeth emerge before the mandibular ones, with the exception of the central incisor and the second molar.9,12,13

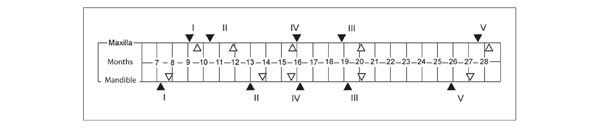

Fig 17-2 Average times of emergence of deciduous teeth in boys (black triangles) and girls (white triangles). I, central deciduous incisors; II, lateral deciduous incisors; III, deciduous canines; IV, first deciduous molars; V, second deciduous molars.

Formation and Emergence of Permanent Teeth

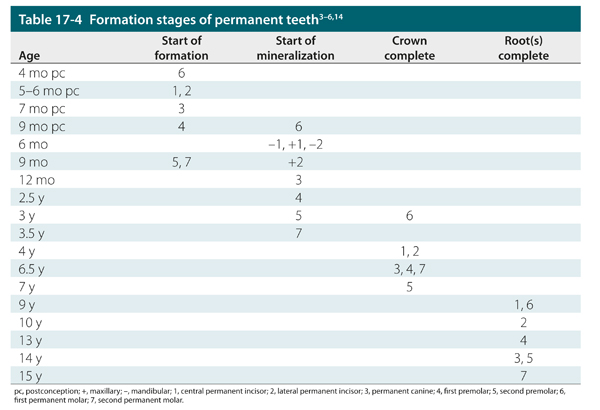

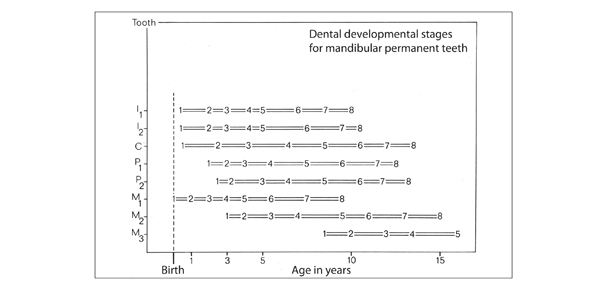

The progress in formation of permanent teeth in relation to age is shown in Table 17-4. In addition, details are provided for the mandibular permanent teeth in Figs 17-3 to 17-5.

Fig 17-5 The eight formation stages (see Figs 17-3 and 17-4) of mandibular permanent teeth plotted against age.7 I1, central incisors; I2, lateral incisors; C, canines; P1, first premolars; P2, second premolars; M1, first molars; M2, second molars; M3, third molars.

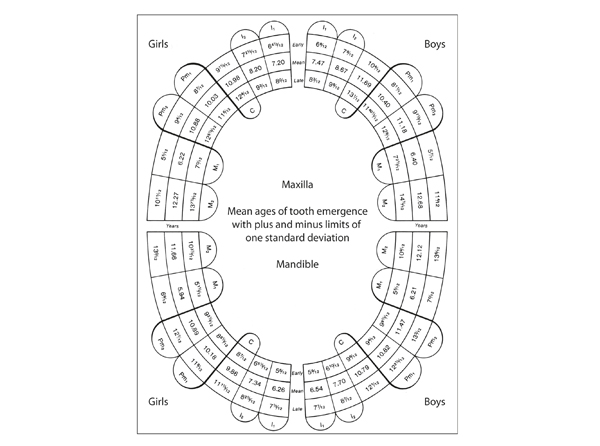

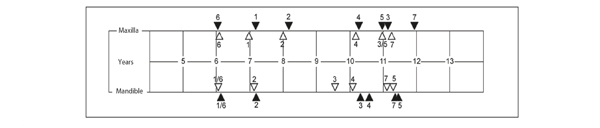

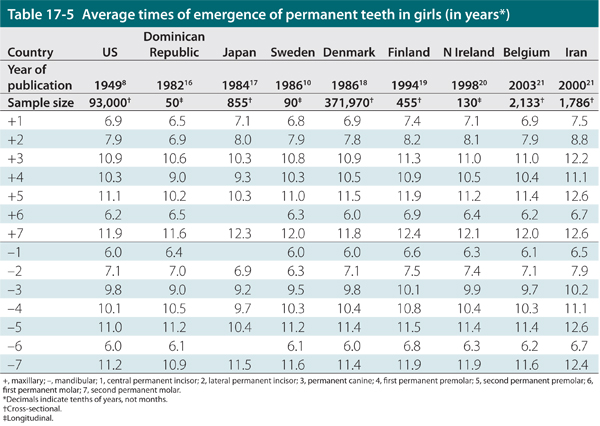

The data on emergence of permanent teeth are presented similarly to those on emergence of deciduous teeth (Figs 17-6 and 17-7 and Tables 17-5 to 17-7). Table 17-5 displays the average times of emergence of permanent teeth in girls. The data were collected in various countries over a period of 40 years. The differences in times of emergence are caused in part by the diversity in the methods of collecting and reporting data and partly by regional and ethnic variability. However, they conform largely in sequence of emergence and also in the phenomenon that mandibular permanent teeth emerge before the maxillary ones. That also applies to the earlier emergence in girls than in boys.

Fig 17-6 Graphic illustration of early, mean, and late times of emergence of permanent teeth for girls (left) and boys (right). The indicated range in times of emergence is representative of twothirds of the population. The data are based on 24 publications, together comprising 93,000 children in the United States and Europe. In those data, which cover one century, little difference appeared in times of emergence. It was evident that the mean times of emergence are 5 months earlier in girls than in boys. The range of variation in times of emergence of corresponding teeth did not differ between the two sexes. However, it did differ among various teeth, with the smallest range for the mandibular first permanent molars, a large range for the maxillary second premolars, and the largest range for the mandibular second premolars. However, the latter can be affected by agenesis. I1, central incisors; I2, lateral incisors; C, canines; P1, first premolars; P2, second premolars; M1, first molars; M2, second molars. (Reprinted from Hurme8 with permission.)

Fig 17-7 Average times of emergence of permanent teeth in boys (black triangles) and girls (white triangles). 1, central incisors; 2, lateral incisors; 3, canines; 4, first premolars; 5, second premolars; 6, first molars; 7, second molars.

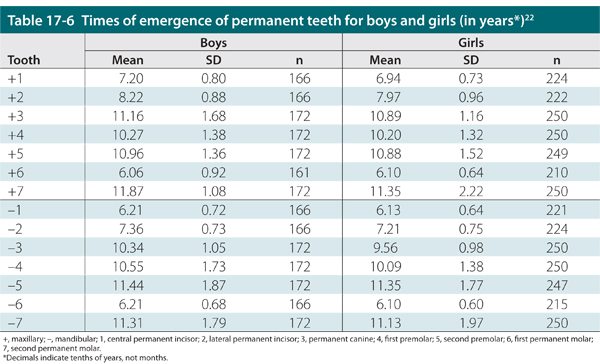

Table 17-6 presents means and standard deviations of times of emergence of permanent teeth derived from the Nijmegen Growth Study.22 These data also show a significant range in times of emergence for all teeth. Twice the standard deviation on both sides of the average encompasses 95% of the population. That means that in boys an emergence of maxillary central permanent incisors between 5.6 and 8.8 years of age cannot be considered outside the norm. For maxillary permanent canines in boys, the range is between 8.8 and 14.5 years. It has to be remarked that the data of times of emergence of the Nijmegen Growth Study deviate only slightly from those of Hurme.8 in Fig 17-6. It provided slightly younger times of emergence, but that could be because in the Nijmegen study, data were collected every 6 months rather than yearly.

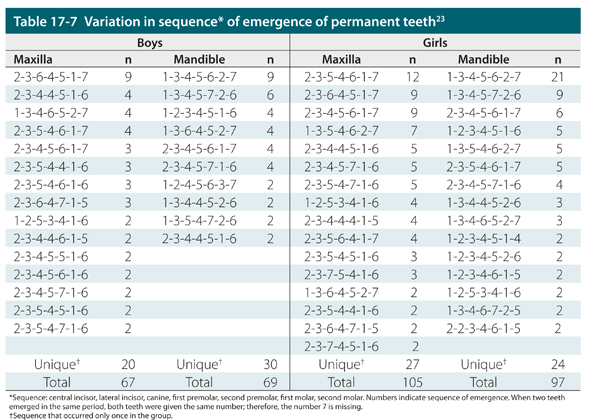

Table 17-7 shows variations in the sequence of emergence of permanent teeth. Striking is the large variation found in the population of 174 children; however, in almost all children, the first permanent molar was the first tooth to emerge in both jaws (indicated by a 1 in the 6th place). A larger variation in times of emergence was recorded for the maxilla than for the mandible, particularly for the canines and premolars.

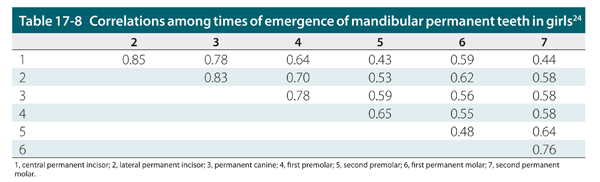

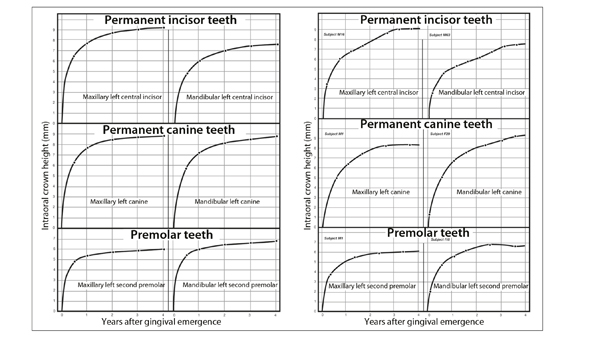

The correlation in times of emergence among mandibular permanent teeth in girls is shown in Table 17-8. The highest correlation in times of emergence is between central and lateral incisors. It is high also between the first and second molars. The rate of eruption after emergence is illustrated in the increase in clinical crown heights (Figs 17-8 and 17-9). The mesiodistal crown dimensions of both dentitions are shown in Table 17-9. There are no differences between boys and girls in the width of deciduous teeth; however, boys have wider permanent tooth crowns than girls, particularly for canines and molars.

Fig 17-8 Average (left) and sample individual (rig/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses