The Geriatric Patient

In developed countries throughout the world, an increasing proportion of the population is aged 65 or older. Japan and Sweden lead the world, with 17% of their population currently over the age of of 65 years. Approximately 13% of the populations of Australia, Canada, Russia, and the United States are over the age of 65 years. In developing countries, such as Mexico, China, and Brazil, approximately 5% of the populations are over the age of 65 years. Although many of the statistical details reported in the first section of this chapter are related to the United States, they are mirrored by similar statistical data for most developed nations in the world. Oral health care for an increasingly large segment of elderly people will be a fact of life for dentists everywhere.

In 1900, the life expectancy at birth in the United States was about 47 years. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, life expectancy has increased to almost 80 years. The average citizen of the United States now has more parents than children,1 and older people are the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population. This chapter discusses treatment-planning issues that have particular relevance to this distinct group. The terms “senior,” “geriatric,” and “older adult” are used interchangeably, all referring to persons older than age 65. Although the authors recognize the arbitrariness of this designation, age 65 has become a common marker for retirement and therefore serves as a standard and convenient reference. Currently, 13% (33 million) of the U.S. population is older than age 65, and this number will almost double by 2030. By the middle of the twenty-first century, the number of centenarians in the United States is expected to reach 1 million.2 Table 16-1 shows life expectancies for adults 55 and older in the United States.

Table 16-1

U.S. Life Expectancy in Years at Age 55 and Beyond (Year 2000 Data)

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. National Center for Health Statistics.

Most older adults (85%) in the United States are healthy and live in community settings. Another 10% are described as homebound (i.e., able to leave their home only with great difficulty). Although on a given day, 5% of U.S. seniors (1.5 million) reside in nursing homes, persons older than age 65 have only a 1-in-4 chance of spending some time in a nursing home during their lifetimes. The proportion of older adults living in nursing homes varies by age, with only 2% of the 65- to 74-year-old group living in that setting, compared with 6% of those 75 to 84, and 22% of those older than age 85. As discussed later in this chapter, access to oral health care can be difficult for nursing home residents and health-compromised homebound persons, and provision of treatment may become more complex as a result of chronic systemic illnesses.

Because of the differential in life expectancies between men and women, aging sometimes is described as a women’s issue. At age 65, there are 123 women for every 100 men in the United States and by age 85, there are 246 women for every 100 men.3 Older women are more likely to be single, divorced, or widowed and as a result, are more likely to live in poverty. Nevertheless, overall, only 12% of older adults live below the poverty level (in contrast to almost 24% of children under age 18). The social programs enacted in the United States in the 1960s (Medicare and Medicaid) have improved the financial status of older adults, and it is encouraging to note that from 1970 to 1995 poverty within the senior age groups has steadily decreased. Although seniors have the lowest income level of any adult age group, income levels vary. Of all older persons, 65- to 74-year-olds have the highest median income, while those older than age 80 have the lowest. Those aged 85 and over are at the greatest risk for poverty. Overall income levels for seniors in the United States are expected to increase as baby boomers, the large cohort of persons born between 1946 and 1964, prepare for retirement.

ORAL HEALTH IN THE AGING POPULATION

Oral health can be both a benchmark for, and a determinant of, the quality of life. Currently, for example, people in the United States who are age 85 can expect to have at least another 5 years of life, but more important than the length of life span is the quality of life that can be afforded to the person in those later years. In the span of the past 20 years, the oral health of older adults in the United States has improved considerably from that of a generation that was predominantly edentulous to one in which each person has an average of 20 teeth.

In general, older adults in the United States have more dental needs, use dental services at higher rates, and incur higher average costs per visit than do younger people.4 Although younger adults have a higher income, seniors may have fewer financial obligations (mortgages are paid, children are raised, and their associated costs have diminished). As a result, seniors can invest their income in themselves, including their oral health. On the negative side, most U.S. dental insurance benefits cease when retirement begins, and Medicare includes almost no dental benefits. For the affluent elderly, dental expenditures often are made from discretionary or expendable income.

For the low-income elderly in the United States, financial options to pay for dental care are limited. Medicaid, available to some, varies from state to state both in types of dental care reimbursed and age groups covered. Even when the patient does qualify, few services are covered beyond basic preventive therapy, direct-fill restorations, extractions, and dentures. A mechanism does exist to use Supplemental Social Security Income to pay for needed dental services if the patient resides in a long-term care facility. Two thirds of those seniors who are considered poor are not eligible for any type of Medicaid dental coverage. For those persons, the prospects for receiving good quality definitive care are limited.5

The trend worldwide is for persons to live longer and to retain more of their natural teeth; as a result, older adults have more complex dental needs. Developed countries with national health systems that include dental care have seen increased costs as their population ages. As oral health costs have increased in this aging population, some governments have examined new ways of preventing oral diseases, particularly root caries. Access to dental care for homebound elderly and nursing home residents can be problematic even in countries with national health care systems.

Changing Needs and Values

In their book Successful Aging, Rowe and Kahn suggest that lifestyle choices may be more important to the aging process than genes.6 The baby boomers are the best educated age group in the U.S. population (almost 25% have attended college). Poised to inherit more than $12 trillion from their World War II—generation parents, they are also potentially the most affluent. Their approach to the aging process differs radically from that of their parents and grandparents. With more leisure time, more discretionary income, more knowledge of wellness issues, and more opportunity to engage in healthful activities, this group is expected to live longer and have higher expectations about their health. They have already demonstrated an increasing demand for discretionary health care services, particularly plastic surgery. Similarly the cosmetic services that dentistry offers have increased in popularity with this group. As the first generation to benefit from the widespread fluoridation of water supplies and the availability of fluoride toothpaste, boomer expectations for oral health include a strong preventive orientation. Already using dental services at a relatively high rate, they are predicted to seek out, appreciate, and benefit from high quality oral health care. As the baby boom generation ages, many in that segment will reach older adulthood with a relatively complete dentition.

Although the expectations of what older individuals want and what they can afford in dental care can and do vary widely, there are also commonalties. Many health problems both oral and systemic are more likely to occur in this population. How are these problems recognized and diagnosed? How are they managed? What are the dental treatment needs of the elderly, and how is dental treatment planning shaped by the characteristics of aging? These questions are the focus of this chapter.

EVALUATION OF THE OLDER PATIENT

Patient Interview

As with patients of any age, establishing a relationship on the right footing requires sensitivity to the person’s particular needs. Although retired, many seniors, especially the younger members of this age group, find themselves with as complex a schedule as they had while working, with involvement in organizations, volunteer work, travel, and hobbies filling busy days and weeks. Many older adults still place a high priority on punctuality and expect the dentist to respect their time. Some older adults spend winter or summer in different locales, often affecting the continuity of both medical and dental care.

Failure to recognize the social issues associated with this age group may impede the development of a good relationship with the patient and, if continued, may become a major barrier to care. If these issues are discussed during the patient interview, both treatment planning and the scheduling of future appointments will be facilitated. Some elderly persons may wish to involve another family member, such as a spouse or adult child, in treatment-planning decisions. It is appropriate to ask the patient if he or she would like to discuss treatment options with another family member before making a decision, while at the same time acknowledging the patient’s autonomy.

For some older patients, special transportation requirements may need to be taken into account when scheduling appointments. The clinician should not hesitate to raise these issues during the patient interview. If the individual depends on a family member to provide transportation to appointments, the number or length of visits may become a patient modifier. Some patients may require a taxi, adding to the expense of the treatment, or require appointments at certain times to accommodate public transportation schedules. Treatment sequencing may need to be altered to accommodate such special situations.

Because the older-than-65 segment of the population spans several generations, individual perceptions of dental needs and treatment choices will differ, based in part on past experiences. It is useful to ask about past dental care and to listen carefully as the patient explains his or her expectations for treatment. Based on what they have learned from previous experiences, some may have low expectations for oral health. Providing information about the changes in dentistry may help enlighten such patients about the available options. The younger elderly (65 to 74 years old) and the soon-to-be-elderly baby boomers are more likely to have higher expectations than those individuals who are 85 or older.

Visual and auditory disabilities are among the most common chronic conditions reported by seniors. Although the office staff should never assume that a patient cannot see or hear well, it is wise to always be aware that these conditions may be present. If a patient has removed his or her glasses for the examination, they should be returned before any written materials are to be reviewed. Black print on a white background is the most easily read. Developing health history forms and written take-home instruction materials in slightly larger print is helpful to many elderly patients.

Close contact with a hearing aid can occur during the initial examination or dental treatment and may cause an unpleasant ringing in the patient’s ear. Because the patient may turn off the hearing aid during treatment, a reminder to turn the aid back on may be needed before beginning any discussion. Written treatment plans or postoperative instructions can assist in the presentation of the information and can be shared with family or friends later, if the patient is reluctant to admit to failing to hear or fully understand the communications in the dental office.

Patient’s Health History

Because older adults are more likely to have chronic health problems, more time is generally required to obtain a thorough and accurate health history. Questioning is necessary to gather additional information about each positive response on the health history form. If a comprehensive health history form is used (see Chapter 1), an ideal format includes space both for patient responses and for the dentist to record notes pertaining to each affirmative answer. It is advisable to assume that the patient can provide a reliable health history until proven otherwise. If the patient seems unable to provide the necessary information, however, a tactful request for assistance should be made to family or caregivers. It also may be advisable to obtain a verbal or written consultation with the patient’s physician. When consulting the patient’s physician, the following guidelines should be observed:

Prescription Medications and the Geriatric Patient

Medications play an important role in maintaining the health and quality of life for many older patients. Although persons older than age 65 currently make up only about 13% of the U.S. population, they consume 30% of all prescription medications. Even healthy community-dwelling seniors have an average of 3 to 4 prescription medications per person, whereas persons living in a long-term care facility commonly have as many as 11 to 13. The patient should be instructed to bring all medications to the dental office on the first visit. Patients should also be queried about any over-the-counter (OTC) medications or herbal remedies they are taking.

A thorough review of the patient’s medication list is an essential component of the health history review and a requisite to the formulation of a comprehensive diagnosis and plan of care. A complete understanding of the types and dosages of the older dental patient’s medications can aid in the differential diagnosis of oral conditions or lesions. It can be a useful indicator of the level of severity of a specific disease and can alert the dentist to potential medical emergencies that may arise during treatment. Because the patient’s medical status and type and dosages of medications can change frequently, it is often helpful to have the patient or care provider bring a list (or medication containers) at least once a year to update the medication history.

It is important to ask if the medications are being used according to the physician’s directions. For various reasons, such as cost, side effects, and difficulty with the timing of multiple medications, patients may not be compliant with the prescribed regimen. Sometimes the individual may choose to use a different dose or frequency based on what he or she believes works best. If the patient is taking multiple medications, he or she may become confused and simply forget to take one or more medications. In any of these situations, the dentist should advise the patient and/or the caregiver to share this information with the patient’s physician. In addition, the dental team should be watchful for signs of undermedication or overmedication. For example, if the patient has chosen to lower the dose of a hypertension medication because of side effects, the dentist should closely monitor the patient’s blood pressure, particularly during a stressful dental procedure.

Examination

A careful initial interview ensures that the dentist is familiar with the patient’s health history, and that during the examination, the clinician is primed to look for signs of any reported diseases or conditions. Procedures for the examination and radiographic selection criteria are the same for the older person as for any adult patient, but certain aspects of the examination are more important for this group.

Because skin cancer is more prevalent in the older population, the dental examination must always include evaluation for signs of head and neck cancer. This may include solar cheilosis or cancer of the lower lip, basal cell carcinomas, or melanomas of the skin. The geriatric patient is much more likely to have osteoporosis that may be evident on the intraoral radiographs, or carotid calcification that is apparent on a panoramic radiograph.

A complete oral examination requires a thorough evaluation of salivary function. Salivary gland dysfunction is more common in seniors than in younger patients. Signs of chronic xerostomia include a desiccated mucosa; a red, fissured, denuded, or shiny tongue; caries around the gingival margins and cusps of teeth; demineralization around the gingival margins, even without obvious caries; bubbly saliva; a high occurrence of soft tissue trauma; and adherence of a gloved finger or mouth mirror to the buccal mucosa. Salivary glands should always be palpated extraorally while viewing the duct to make sure an adequate flow of saliva occurs when the glands are massaged.7 Patients also should be questioned about any history of pain or swelling in the glandular areas that could indicate infection, blockage, or neoplasm.

Risk Assessment

As James Beck has noted, the relative importance of risk factors changes as people age.8 For older adults, systemic disease and medications play a far greater role in oral health than is true of younger adults. Alzheimer’s disease, arthritis, or stroke can impair the patient’s ability to perform daily oral hygiene. The varying causes of impairment require different solutions. Changes in both hard and soft oral tissues occur with age. Box 16-1 provides a list of some of the oral problems most common among older patients. Physiologic changes in the teeth include a darkening of the color, a decrease in pulpal size, attrition, and decreased pulpal cellularity. As the pulp recedes, teeth may become more brittle and are at increased risk for fracture.

Studies have shown that older adults continue to be at risk for root caries and recurrent caries around old or worn restorations.9–11 Gingival recession, decreased salivary flow (often secondary to medication use), and poor oral hygiene can increase the risk for root caries.

Although the prevalence of periodontal disease increases among the elderly, age, in and of itself, is not a risk factor for gingivitis or periodontal diseases. Gingivitis and loss of periodontal attachment are bacterially mediated processes and if the bacteria can be controlled, these diseases can be prevented. Recent research on the relationship between systemic conditions and periodontal disease in adults has identified diabetes and tobacco use as increasing the risk for this problem. Poor oral self care and the use of certain medications can increase the risk of gingivitis. Although gingival recession occurs frequently in older adults, age is not necessarily a risk factor. Known risk factors for gingival recession include periodontal disease, poor oral self care, and dysfunctional habits, such as scrubbing with a hard toothbrush and clenching or bruxing the teeth.

The oral mucosa continues to play a critical role as a barrier organ for the body throughout life. Although there is little change in the thickness of stratified squamous epithelium on the surface (except under dentures), the connective tissue layer below becomes thinner and loses elasticity, decreasing the effectiveness of the barrier function. In addition, a reduced immune response may increase the vulnerability of oral tissues to infection and trauma. The incidence of oral mucosal disorders increases with advancing age. Such diseases include vesiculobullous disorders; ulcerative lesions secondary to medication use; and lichenoid, infectious, and malignant lesions. Alcohol and tobacco use are important risk factors for oral cancer (see Chapter 11).

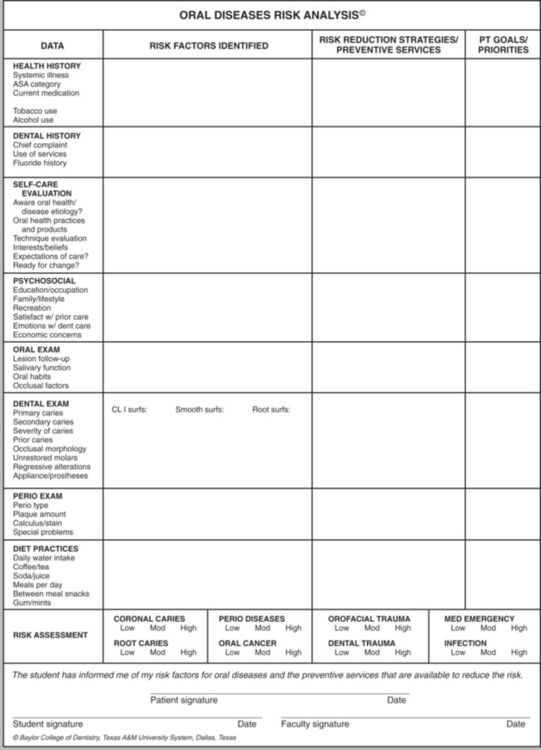

When risk factors have been identified, risk reduction strategies can be designed to reduce or eliminate their impact. Figure 16-1 illustrates the Oral Diseases Risk Analysis form. This form serves to identify and categorize risk factors so that strategies can be developed to prevent the occurrence or recurrence of disease. Although not all such factors can be eliminated (e.g., systemic diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease or hemiparesis as a result of cerebrovascular accident), identifying the risk factors enables both the dentist and the patient to work on creative ways to reduce their impact. In patients with multiple risk factors, column 4 of the form enables the dental team member to annotate discussion of the reduction strategy and monitor the patient’s progress. Patients in turn can decide which problems they wish to address and in what sequence, thus empowering them to take responsibility for their own oral health.

Identifying Health Problems That May Affect Dental Treatment

With increasing age, the probability of systemic illness also increases. Optimal treatment planning for older adults requires an understanding of the overall health of the patient, and the relationship between any systemic problem and the patient’s oral health. The leading causes of death in U.S. adults older than age 65 include heart disease, cancer, stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease. Treatment planning must therefore include an assessment of any chronic conditions and of the likelihood that such a condition will increase the patient’s risk for oral disease. For example, a systemic disease that compromises the immune system may result in a Candida infection in the oral cavity. Patients with chronic gastrointestinal problems may have a lower oral pH because of constant acid reflux, leading to increased risk of oral disease or an unusual pattern of oral disease (Figure 16-2). Each time an older patient’s health history is reviewed, the dentist needs to consider what impact any new illness may have on the patient’s oral cavity.

Figure 16-2 Patient with oral problems caused by severe acid reflux. The impact of systemic disease can be devastating to the oral cavity. This patient, who was diagnosed with severe gastroesophageal reflux, exhibits a high caries rate around the gum line and on the cusps because of the low pH in the oral cavity.

Box 16-2 lists the most likely chronic conditions with which an older patient will present to an examining dentist, many of which can have a direct impact on oral health and dental care. Arthritis, the most common condition, may affect an individual’s ability to perform daily brushing or flossing. Hearing and vision impairment can hinder the patient’s ability to comprehend a treatment plan, or even the ability to travel to the dental office. Uncontrolled diabetics are more prone to severe periodontal disease, and patients taking chronic allergy medications may suffer from dry mouth.

Because senior patients are more likely to be taking medications, they are also more likely to develop medication-related oral changes. A medication reference book written for the dental profession (or an online medication database) can help in identifying the oral side effects of medications. Drug-drug interactions increase with the number of medications used; 50% of patients taking at least four medications will have some type of drug-drug interaction. A significant portion of these drug interactions occurs with antibiotics, analgesics, and sedatives medications frequently prescribed by dentists. Thankfully, most side effects and interactions are mild, and many go unnoticed. Nevertheless, it is important for the clinician to be alert to the possibility of this type of problem. Table 16-2 lists some of the common adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions seen with medications frequently prescribed in association with dental treatment.

Table 16-2

Possible Adverse Drug Reactions and Drug-Drug Interactions Adapted from Bandrowsky T and others: Amoxicillin-related postextraction bleeding in an anticoagulated patient with tranexamic acid rinses, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 82:610-612, 1996.

| Drug or Drug Class | Possible Adverse Drug Reaction or Interaction |

| Aspirin | May reduce platelet aggregation or increase warfarin levels, resulting in possible excessive bleeding |

| Antibiotics (long term 7 days or more) | May reduce intrinsic intestinal bacteria levels with resultant reduced absorption of vitamin K; may increase warfarin levels, resulting in a deficiency of certain clotting factors |

| Calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine) | May cause gingival overgrowth |

| Cyclosporine | May cause gingival overgrowth |

| Erythromycin | Can increase digoxin to toxic levels or increase warfarin levels, resulting in risk of excessive bleeding |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | May increase warfarin levels, resulting in excessive bleeding |

| Phenytoin | May cause gingival overgrowth |

Treatment planning and pretreatment evaluation of any patient require an assessment of the need for anti-biotic premedication for the prevention of bacterial endocarditis. More than half of all cases of bacterial endocarditis in the United States occur in persons older than the age of 60, and 42% of institutionalized elderly may have at least one cardiac risk factor for infective endocarditis.12,13

The presence of a prosthetic joint replacement is often cited as an indication for antibiotic premedication before an invasive dental procedure. As discussed in the What’s the Evidence? box, although the American Dental Association and the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons have published a joint advisory statement on this issue, the question of whether patients with major prosthetic joint replacement need antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment remains controversial. Physicians and dentists increasingly agree, however, that for patients whose prosthetic joint has been in place for 2 years or longer and who have no other risk factors, antibiotic premedication is not warranted. Some orthopedists may still recommend antibiotic premedication even for these low-risk patients, however.

Alterations in mastication, swallowing, and sensory function (taste and smell) do occur with age. Mastication and swallowing difficulties often occur as sequelae of systemic diseases, such as stroke or Parkinson’s disease, or the use of antipsychotic medications. The ability to taste appears to undergo few age-related alterations. The sense of smell, however, appears to decrease with age, and is thought to account for loss of flavor perception in older adults.

Xerostomia

More than 400 medications can cause xerostomia or dry mouth. Sedatives, antipsychotics, antidepressants, antihistamines, diuretics, and some hypertension medications are among the most frequently cited examples. The actual mechanisms for xerostomia associated with medication use vary and are not always well understood. Medications with anticholinergic activity neurologically reduce saliva flow. Other drugs may dehydrate the oral tissues, causing the sensation of oral dryness.

Xerostomia has long been thought to be a natural part of aging. We now know that although changes associated with aging occur in the salivary glands, in healthy older adults adequate salivary flow is maintained throughout life.14 Salivary flow or function usually will have decreased by at least 50% before a person becomes symptomatic or complains of oral dryness. Treatment planning for older adults must address the complaint of xerostomia, and identify the underlying cause of this symptom.

Box 16-3 lists some of the most common diagnoses associated with xerostomia. Medication side effects are the most frequently cited cause, but in the differential diagnosis many other systemic diseases must also be suspect. Some systemic diseases, such as Sjögren’s syndrome, actually damage the glands, and preclude any stimulated flow. This chronic inflammatory or autoimmune disorder affects primarily the salivary and lacrimal glands. Glandular tissue is permanently destroyed by lymphocytic infiltration. The disease is often associated with other autoimmune disorders, and is accompanied by systemic symptoms, such as dryness of pulmonary, genital, and dermal tissue; dry eyes; and/or dry mouth.

Many insulin-dependent diabetic patients are xerostomic, but the literature to date has been inconclusive as to whether salivary gland function is reduced in all diabetics. Poor glycemic control and subsequent dehydration may cause this symptom.

Generalized dehydration is also more common in the senior population and probably contributes more to xerostomia than previously understood. With aging comes a decrease in the sense of thirst, increasing the chance of dehydration and subsequently decreasing fluid output of all types.

Radiation treatment for head and neck malignancies destroys salivary gland tissue within the radiation field. Oral dryness can begin as early as 2 weeks into the radiation treatment. The remaining salivary flow is described as thick and is often associated with an alteration />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses