Principles of Management and Prevention of Odontogenic Infections

Thomas R. Flynn

In dentistry, one of the most difficult problems to manage is an odontogenic infection. Odontogenic infections arise from teeth and have a characteristic flora. Caries, periodontal disease, and pulpitis are the initiating infections, that can spread beyond teeth to the alveolar process and to the deeper tissues of the face, oral cavity, head, and neck. These infections may range from low-grade, well-localized infections that require only minimal treatment to severe, life-threatening deep fascial space infections. Although the overwhelming majority of odontogenic infections are readily managed by minor surgical procedures and supportive medical therapy that includes antibiotic administration, the practitioner must constantly bear in mind that these infections occasionally become severe and life threatening within a short time.

This chapter is divided into several sections. The first section discusses the typical microbiologic organisms involved in odontogenic infections. Appropriate therapy of odontogenic infections depends on a clear understanding of the causative bacteria. The second section discusses the natural history of odontogenic infections. When infections occur, they may erode through bone and into the adjacent soft tissue. Knowledge of the usual pathway of infection from the teeth and surrounding tissues through bone and into the overlying soft tissue planes is essential when planning appropriate therapy. The third section of this chapter deals with the principles of management of odontogenic infections. A series of principles are discussed, with consideration of the microbiology and typical pathways of infection. The chapter concludes with a section on the prophylaxis of wound infection and of metastatic infection.

Microbiology of Odontogenic Infections

The bacteria that cause infection are most commonly part of the indigenous bacteria that normally live on or in the host. Odontogenic infections are no exception because the bacteria that cause odontogenic infections are part of the normal oral flora: those that comprise the bacteria of plaque, those found on mucosal surfaces, and those found in the gingival sulcus. These bacteria are primarily aerobic gram-positive cocci, anaerobic gram-positive cocci, and anaerobic gram-negative rods. These bacteria cause a variety of common diseases such as dental caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis. When these bacteria gain access to deeper underlying tissues, as through a necrotic dental pulp or through a deep periodontal pocket, they cause odontogenic infections. As the infection progresses more deeply, different members of the infecting flora can find better growth conditions and begin to outnumber the previously dominant species.

Many carefully performed microbiologic studies of odontogenic infections have demonstrated the microbiologic composition of these infections. Several important factors must be noted. First, almost all odontogenic infections are caused by multiple bacteria. The polymicrobial nature of these infections makes it important that the clinician understand the variety of bacteria that are likely to cause infection. In most odontogenic infections, the laboratory can identify an average of five species of bacteria. It is not unusual to identify as many as eight different species in a given infection. On rare occasions, a single species may be isolated. New molecular methods, which identify the infecting species by their genetic makeup, have allowed scientists to identify greater numbers and a whole new range of species, including unculturable pathogens, not previously associated with these infections. In the future, these methods may lead to a completely new understanding of the pathogenesis of odontogenic infections.

A second important factor is the oxygen tolerance of the bacteria that cause odontogenic infections. Because the mouth flora is a combination of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, it is not surprising to find that most odontogenic infections are caused by anaerobic and aerobic bacteria. Infections caused by aerobic bacteria alone account for 6% of all odontogenic infections. Anaerobic bacteria alone are found in 44% of odontogenic infections. Infections caused by mixed anaerobic and aerobic bacteria comprise 50% of all odontogenic infections (Table 16-1).

Table 16-1

Role of Anaerobic Bacteria in Odontogenic Infections

| Percentage | |

| Anaerobic only | 50 |

| Mixed anaerobic and aerobic | 44 |

| Aerobic only | 6 |

Data from Brook I, Frazier EH, Gher ME: Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of periapical abscess. Oral Microbiol Immunol 6:123–125, 1991.

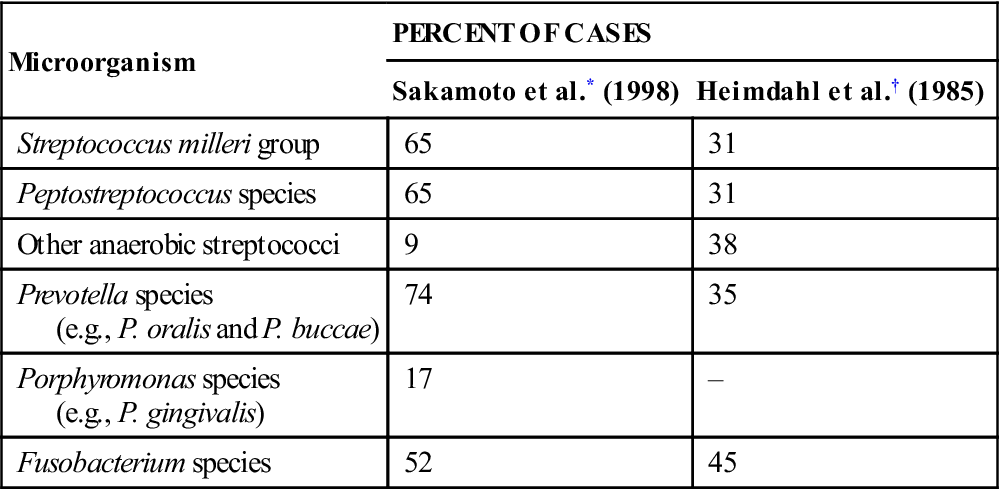

The predominant aerobic bacteria in odontogenic infections (found in about 65% of cases) are the Streptococcus milleri group, which consists of three members of the S. viridans group of bacteria: S. anginosus, S. intermedius, and S. constellatus. These facultative organisms, which can grow in the presence or the absence of oxygen, may initiate the process of spreading into deeper tissue (Table 16-2). Miscellaneous bacteria contribute 5% or less of the aerobic species found in these infections. Rarely found bacteria include staphylococci, group D Streptococcus organisms, other streptococci, Neisseria spp., Corynebacterium spp., and Haemophilus spp.

Table 16-2

Major Pathogens in Odontogenic Infections

< ?comst?>

| Microorganism | PERCENT OF CASES | |

| Sakamoto et al.* (1998) | Heimdahl et al.† (1985) | |

| Streptococcus milleri group | 65 | 31 |

| Peptostreptococcus species | 65 | 31 |

| Other anaerobic streptococci | 9 | 38 |

| Prevotella species (e.g., P. oralis and P. buccae) |

74 | 35 |

| Porphyromonas species (e.g., P. gingivalis) |

17 | – |

| Fusobacterium species | 52 | 45 |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>*< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>Data from Sakamoto H, Kato H, Sato T, Sasaki J: Semiquantitative bacteriology of closed odontogenic abscesses. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 39:103–107, 1998.

< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>†< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>Heimdahl A, Von Konow L, Satoh T, et al: Clinical appearance of orofacial infections of odontogenic origin in relation to microbiological findings. J Clin Microbiol 22:299, 1985.

The anaerobic bacteria found in odontogenic infections include an even greater variety of species (see Table 16-2). Two main groups, however, predominate. The anaerobic gram-positive cocci are found in about 65% of cases. These cocci are anaerobic Streptococcus and Peptostreptococcus. Oral gram-negative anaerobic rods are cultured in about three quarters of the infections. The Prevotella and Porphyromonas spp. are found in about 75% of these, and Fusobacterium organisms are present in more than 50%.

Of the anaerobic bacteria, several gram-positive cocci (i.e., anaerobic Streptococcus and Peptostreptococcus spp.) and gram-negative rods (i.e., Prevotella and Fusobacterium spp.) play a more important pathogenic role. The anaerobic gram-negative cocci and the anaerobic gram-positive rods appear to have little or no role in the cause of odontogenic infections; instead, they appear to be opportunistic organisms.

The method by which mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacteria cause infections is known with some certainty. After initial inoculation into deeper tissues, the facultative S. milleri group organisms can synthesize hyaluronidase, which allows the infecting organisms to spread through connective tissues, initiating the cellulitis stage of infection. Metabolic byproducts from the streptococci create a favorable environment for the growth of anaerobes: the release of essential nutrients, lowered pH in the tissues, and consumption of local oxygen supplies. The anaerobic bacteria are then able to grow, and as the local oxidation–reduction potential is lowered further, the anaerobic bacteria predominate and cause liquefaction necrosis of tissues by their synthesis of collagenases. As collagen is broken down and invading white blood cells necrose and lyse, microabscesses form and may coalesce into a clinically recognizable abscess. In the abscess stage, anaerobic bacteria predominate and may eventually become the only organisms found in culture. Early infections appearing initially as a cellulitis may be characterized as predominantly aerobic streptococcal infections, and late, chronic abscesses may be characterized as anaerobic infections.

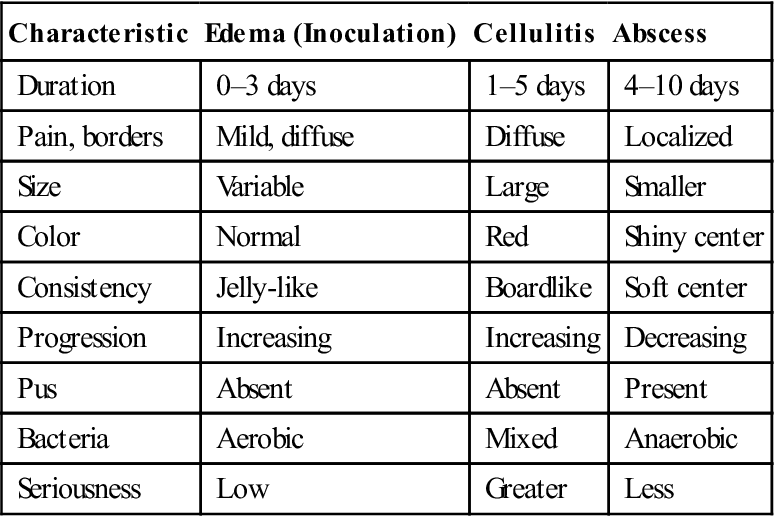

Clinically, this progression of the infecting flora from aerobic to anaerobic seems to correlate with the type of swelling that can be found in the infected region. Thus, odontogenic infections seem to pass through four stages. In the first 3 days of symptoms, a soft, mildly tender, doughy swelling represents the inoculation stage, in which the invading streptococci are just beginning to colonize the host. After 3 to 5 days, the swelling becomes hard, red, and acutely tender as the infecting mixed flora stimulates the intense inflammatory response of the cellulitis stage. At 5 to 7 days after the onset of swelling, the anaerobes begin to predominate, causing a liquefied abscess in the center of the swollen area. This is the abscess stage. Finally, when the abscess drains spontaneously through skin or mucosa, or it is surgically drained, the resolution stage begins as the immune system destroys the infecting bacteria, and the processes of healing and repair ensue. The clinical and microbiologic characteristics of edema, cellulitis, and abscess are summarized and compared in Table 16-3.

Table 16-3

Comparison of Edema, Cellulitis, and Abscess

< ?comst?>

| Characteristic | Edema (Inoculation) | Cellulitis | Abscess |

| Duration | 0–3 days | 1–5 days | 4–10 days |

| Pain, borders | Mild, diffuse | Diffuse | Localized |

| Size | Variable | Large | Smaller |

| Color | Normal | Red | Shiny center |

| Consistency | Jelly-like | Boardlike | Soft center |

| Progression | Increasing | Increasing | Decreasing |

| Pus | Absent | Absent | Present |

| Bacteria | Aerobic | Mixed | Anaerobic |

| Seriousness | Low | Greater | Less |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Natural History of Progression of Odontogenic Infections

Odontogenic infections have two major origins: (1) periapical, as a result of pulpal necrosis and subsequent bacterial invasion into the periapical tissue, and (2) periodontal, as a result of a deep periodontal pocket that allows inoculation of bacteria into the underlying soft tissues. Of these two, the periapical origin is the most common in odontogenic infections.

Necrosis of the dental pulp as a result of deep caries allows a pathway for bacteria to enter the periapical tissues. Once this tissue has become inoculated with bacteria and an active infection is established, the infection spreads equally in all directions, but preferentially along the lines of least resistance. The infection spreads through the cancellous bone until it encounters a cortical plate. If this cortical plate is thin, the infection erodes through the bone and enters the surrounding soft tissues. Treatment of the necrotic pulp by standard endodontic therapy or extraction of the tooth should resolve the infection. Antibiotics alone may arrest, but do not cure, the infection because the infection is likely to recur when antibiotic therapy has ended without treatment of the underlying dental cause. Thus, the primary treatment of pulpal infections is endodontic therapy or tooth extraction, as opposed to antibiotics.

When the infection erodes through the cortical plate of the alveolar process, it spreads into predictable anatomic locations. The location of the infection arising from a specific tooth is determined by the following two major factors: (1) the thickness of the bone overlying the apex of the tooth and (2) the relationship of the site of perforation of bone to muscle attachments of the maxilla and mandible.

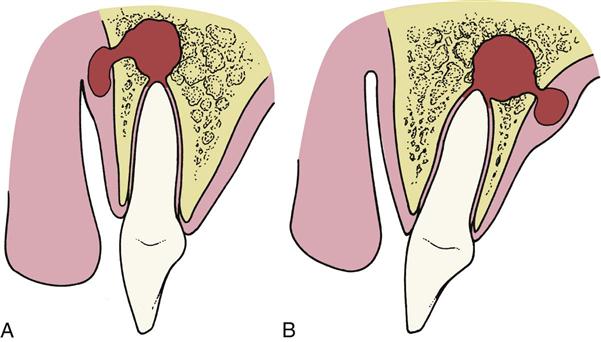

Figure 16-1 demonstrates how infections perforate through bone into the overlying soft tissue. In Figure 16-1, A, the labial bone overlying the apex of the tooth is thin compared with the bone on the palatal aspect of the tooth. Therefore, as the infectious process spreads, it goes into the labial soft tissues. In Figure 16-1, B, the tooth is severely proclined, which results in thicker labial bone and a relatively thinner palatal bone. In this situation, as the infection spreads through bone into the soft tissue, the infection is seen as a palatal abscess.

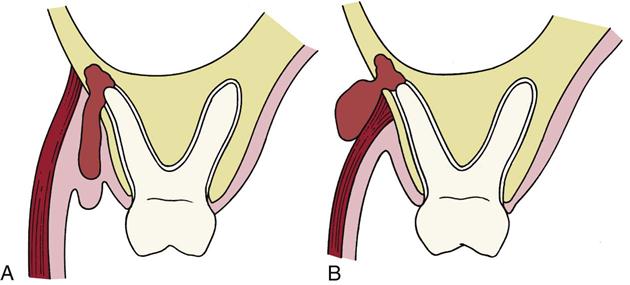

Once the infection has eroded through bone, the precise location of the soft tissue infection is determined by the position of the perforation relative to the muscle attachments. In Figure 16-2, A, the infection has eroded through to the facial aspect of the alveolar process and inferior to the attachment of the buccinator muscle, which results in an infection that appears as a vestibular abscess. In Figure 16-2, B, the infection has eroded through the bone superior to the attachment of the buccinator muscle and is expressed as an infection of the buccal space because the buccinator muscle separates the buccal and vestibular spaces.

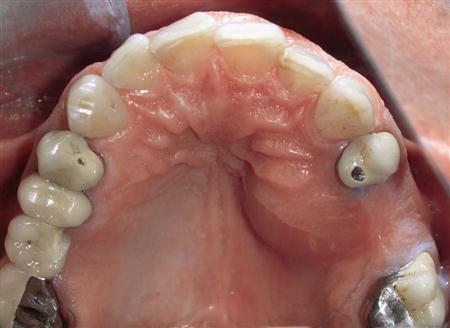

Infections from most of the maxillary teeth erode through the facial cortical plate. These infections also erode through the bone below the attachment of the muscles that attach to the maxilla, which means that most maxillary dental abscesses appear initially as vestibular abscesses. Occasionally, a palatal abscess arises from the apex of a severely inclined lateral incisor or the palatal root of a maxillary first molar or premolar (Fig. 16-3). More commonly, the maxillary molars cause infections that erode through the bone superior to the insertion of the buccinator muscle, which results in a buccal space infection. Likewise, on occasion a long maxillary canine root allows infection to erode through the bone superior to the insertion of the levator anguli oris muscle and causes an infraorbital (canine) space infection.

In the mandible, infections of incisors, canines, and premolars usually erode through the facial cortical plate superior to the attachment of the muscles of the lower lip, resulting in vestibular abscesses. Mandibular molar infections erode through the lingual cortical bone more frequently than in the case of the anterior teeth. First molar infections may drain buccally or lingually. Infections of the second molar can perforate buccally or lingually (but usually lingually), and third molar infections almost always erode through the lingual cortical plate. The mylohyoid muscle determines whether infections that drain lingually go superior to that muscle into the sublingual space or below it into the submandibular space.

The most common odontogenic deep fascial space infection is a vestibular space abscess (Fig. 16-4). Occasionally, patients do not seek treatment for these infections, and the process ruptures spontaneously and drains, resulting in resolution or chronicity of the infection. The infection recurs if the site of spontaneous drainage closes. Sometimes, the abscess establishes a chronic sinus tract that drains to the oral cavity or to skin (Fig. 16-5). As long as the sinus tract continues to drain, the patient experiences no pain. Antibiotic administration usually stops the drainage of infected material temporarily, but when the antibiotic course is over, the drainage recurs. Definitive treatment of a chronic sinus tract requires treatment of the original causative problem, which is usually a necrotic pulp. In such a case, the necessary treatment is endodontic surgery or extraction of the infected tooth.

Principles of Therapy of Odontogenic Infections

This section discusses the management of odontogenic infections. A series of principles are useful in treating patients who come to the dentist with infections related to teeth and the gingiva. The clinician must keep in mind the information in the preceding two sections of this chapter to understand these principles. By following these principles in a stepwise fashion, the clinician will certainly have met the standard of care, even though the expected result may not always be achieved. The first three principles are perhaps the most important in determining the outcome, yet they can be accomplished by the experienced practitioner within the first few minutes of the initial patient encounter.

Principle 1: Determine Severity of Infection

Most odontogenic infections are mild and require only minor surgical therapy. When the patient comes for treatment, the initial goal is to assess the severity of the infection. This determination is based on a complete history of the current infectious illness and a physical examination.

Complete history.

The history of the patient’s infection follows the same general guidelines as those for any history. The initial purpose is to find out the patient’s chief complaint. Typical chief complaints of patients with infections are “I have a toothache,” “My jaw is swollen,” or “I have a gum boil in my mouth.” The complaint should be recorded in the patient’s own words.

The next step in history taking is determining how long the infection has been present. First, the dentist should inquire as to time of onset of the infection. How long ago did the patient first have symptoms of pain, swelling, or drainage, which indicated the beginning of the infection? The course of the infection is then discussed. Have the symptoms of the infection been constant, have they waxed and waned, or has the patient’s condition steadily grown worse since the symptoms were first noted? Finally, the practitioner should determine the rapidity of progress of the infection. Has the infection process progressed rapidly over a few hours, or has it gradually increased in severity over several days to a week?

The next step is eliciting information about the patient’s symptoms. Infections are actually a severe inflammatory response, and the cardinal signs of inflammation are clinically easy to discern. These signs and symptoms are, in Latin terms, dolor (pain), tumor (swelling), calor (warmth), rubor (erythema, redness), and functio laesa (loss of function).

The most common complaint is pain. The patient should be asked where the pain actually started and how the pain has spread since it was first noted. The second sign is tumor (swelling), which is a physical finding that is sometimes subtle and not obvious to the practitioner, although it is obvious to the patient. It is important that the dentist ask the patient to describe any area of swelling. With regard to the third characteristic of infection, calor (warmth), the patient should be asked whether the area has felt warm to the touch. Redness of the overlying area is the next characteristic to be evaluated. The patient should be asked if there has been or is any change in color, especially redness, over the area of the infection. Functio laesa (loss of function) should then be checked. When inquiring about this characteristic, the dentist should ask about trismus (difficulty opening the mouth widely) and any difficulty chewing, swallowing (dysphagia), or breathing (dyspnea).

Finally, the dentist should ask how the patient feels in general. Patients who feel fatigued, feverish, weak, and sick are said to have malaise. Malaise usually indicates a generalized reaction to a moderate-to-severe infection (Fig. 16-6).

In the next step, the dentist discusses treatment. The dentist should find out about previous professional treatment and self-treatment. Many patients treat themselves with leftover antibiotics, hot soaks, and a variety of other home or herbal remedies. Occasionally, a dentist may see a patient who had received treatment in an emergency room 2 or 3 days earlier and was referred to a dentist by the emergency room physician. The patient might have neglected to follow the emergency room physician’s advice until the infection became severe. Sometimes, the patient may not have taken the prescribed antibiotic because he or she could not afford to purchase it.

The patient’s complete medical history should be obtained in the usual manner through an interview or a self-administered questionnaire with verbal follow-up of any relevant findings.

Physical examination.

The first step in the physical examination is to obtain the patient’s vital signs, including temperature, blood pressure, pulse rate, and respiratory rate. The need for evaluation of temperature is obvious. Patients who have systemic involvement of infection usually have elevated temperatures. Patients with severe infections have temperatures elevated to 101°F or higher (greater than 38.3°C).

The patient’s pulse rate increases as the patient’s temperature increases. Pulse rates of up to 100 beats per minute (beats/min) are not uncommon in patients with infections. If pulse rates increase to greater than 100 beats/min, the patient may have a severe infection and should be treated more aggressively.

The vital sign that varies the least with infection is the patient’s blood pressure. Only if the patient has significant pain and anxiety will an elevation occur in systolic blood pressure. However, septic shock results in hypotension.

Finally, the patient’s respiratory rate should be closely observed. One of the major considerations in odontogenic infections is the potential for partial or complete upper airway obstruction as a result of extension of the infection into the deep fascial spaces of the neck. As respirations are monitored, the dentist should carefully check to ensure that the upper airway is clear and that the patient is able to breathe without difficulty. The normal respiratory rate is 14 to 16 breaths per minute (breaths/min). Patients with mild to moderate infections may have elevated respiratory rates greater than 18 breaths/min.

Patients who have normal vital signs with only a mild temperature elevation usually have a mild infection that can be readily treated. Patients who have abnormal vital signs with elevation of temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rate are more likely to have serious infection and require more intensive therapy and evaluation by an oral-maxillofacial surgeon.

Once vital signs have been taken, attention should be turned to the physical examination of the patient. The initial portion of the physical examination should be inspection of the patient’s general appearance. Patients who have more than a minor, localized infection have an appearance of fatigue, feverishness, and malaise. This is referred to as a “toxic appearance” (see Fig. 16-6).

The patient’s head and neck should be carefully examined for the cardinal signs of infection (as discussed earlier), and the patient should be inspected for any evidence of swelling and overlying erythema. The patient should be asked to open the mouth widely, swallow, and take deep breaths so that the dentist can check for trismus, dysphagia, or dyspnea. These are ominous signs of a severe infection, and the patient should be referred immediately to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon or to the emergency room. A recent study of severe odontogenic infections requiring hospitalization found trismus (maximum interincisal opening less than 20 mm) in 73% of cases, dysphagia in 78%, and dyspnea in 14%.

Areas of swelling must be examined by palpation. The dentist should gently touch the area of swelling to check for tenderness, amount of local warmth or heat, and the consistency of the swelling. The consistency of the swelling may vary from very soft and almost normal to a firmer, fleshy swelling (described as “doughy”) to an even firmer or hard swelling (described as “indurated”). An indurated swelling has similar firmness to a tightened muscle. Another characteristic consistency is fluctuance. Fluctuance feels like a fluid-filled balloon. Fluctuant swelling almost always indicates an accumulation of liquid pus in the center of an indurated area.

The dentist then performs an intraoral examination to try to find the specific cause of the infection. Severely carious teeth, an obvious periodontal abscess, severe periodontal disease, combinations of caries and periodontal disease, or an infected fracture of a tooth or the entire jaw may be present. The dentist should look and feel for areas of gingival swelling and fluctuance and for localized vestibular swellings or draining sinus tracts.

The next step is to perform a radiographic examination. This usually consists of the indicated periapical radiographs. Occasionally, however, extraoral radiographs such as a panoramic radiograph may be necessary because of limited mouth opening, tenderness, or other extenuating circumstances.

After the physical examination, the practitioner should begin to have a sense of the stage of the presenting infection. Very soft, mildly tender, edematous swellings indicate the inoculation stage, whereas an indurated swelling indicates the cellulitis stage (Fig. 16-7), and central fluctuance indicates an abscess (Fig. 16-8). Soft tissue infections in the inoculation stage may be cured by removal of the odontogenic cause, with or without supportive antibiotics; infections in the cellulitis or abscess stages require removal of the dental cause of infection plus incision and drainage and antibiotics.

Distinctions between the inoculation, cellulitis, and abscess stages are typically related to duration, pain, size, peripheral definition and consistency on palpation, presence of purulence, infecting bacteria, and potential danger (see Table 16-3). The duration of cellulitis is usually thought to be acute and is the most severe presentation of infection. An abscess, however, is a sign of increasing host resistance to infection. Cellulitis is usually described as being more painful than an abscess, which may be the result of its acute onset and tissue distention.

Edema, the hallmark of the inoculation stage, is typically diffuse and jelly-like, with minimal tenderness to palpation. The size of a cellulitis is typically larger and more widespread than that of an abscess or edema. The periphery of a cellulitis is usually indistinct, with a diffuse border that makes it difficult to determine where the swelling begins or where it ends. The abscess usually has distinct and well-defined borders. Consistency to palpation is one of the primary distinctions among the stages of infection. When palpated, edema can be very soft or doughy; a severe cellulitis is almost always described as indurated or even as being “boardlike.” The severity of the cellulitis increases as its firmness to palpation increases. On palpation, an abscess feels fluctuant because it is a pus-filled tissue cavity. Thus, an infection may appear innocuous in its early stages and extremely dangerous in its more advanced, indurated, rapidly spreading stages. A localized abscess is typically less dangerous because it is more chronic and less aggressive.

The presence of pus usually indicates that the body has locally walled off the infection and that the local host resistance mechanisms are bringing the infection under control. In many clinical situations, the distinction between severe cellulitis and abscess may be difficult to make, especially if an abscess lies deeply within the soft tissue. In some patients, an indurated cellulitis may have areas of abscess formation within it (see Chapter 17).

Severe infections occupying multiple deep fascial spaces may be in an early stage in one anatomic space, and in a more severe, rapidly progressive stage in another fascial space. A severe, deeply invading infection may pass through ever deeper anatomic spaces in a predictable fashion, similar to a house fire, where smoke may be present in one room, intense heat in another, and open flames near the source of the fire. The goal of therapy in such infections is to abort the spread of the infection in all involved anatomic spaces. These infections are discussed in detail in Chapter 17.

In summary, edema represents the earliest inoculation stage of infection which is most easily treated. Cellulitis is an acute, painful infection with more swelling and diffuse borders. Cellulitis has a hard consistency on palpation and contains no visible pus. Cellulitis may be a rapidly spreading process in serious infections. An acute abscess is a more mature infection with more localized pain, less swelling, and well-circumscribed borders. The abscess is fluctuant on palpation because it is a pus-filled tissue cavity. A chronic abscess is usually slow growing and less serious than cellulitis, especially if the abscess has drained spontaneously to the external environment.

Principle 2: Evaluate State of Patient’s Host Defense Mechanisms

Part of the evaluation of the patient’s medical history is designed to estimate the patient’s ability to defend against infection. Several disease states and several types of drug use may compromise this ability. Immunocompromised patients are more likely to have infections, and these infections often become serious more rapidly. Therefore, to manage their infections more effectively, it is important to be able to identify those patients who may have compromised host defenses.

Medical conditions that compromise host defenses.

Delineation of those medical conditions that may result in decreased host defenses is important. These compromises allow more bacteria to enter the tissues or to be more active, or they prevent the humoral or cellular defenses from exerting their full effect. Several specific conditions may compromise patients’ defenses (Box 16-1).

Uncontrolled metabolic diseases—such as uncontrolled diabetes, end-stage renal disease with uremia, and severe alcoholism with malnutrition—result in decreased function of leukocytes, including decreased chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and bacterial killing. Of these metabolic diseases, poorly controlled type 1 (insulin-dependent) and type 2 (non–insulin-dependent) diabetes are the most common immunocompromising diseases, and worsening control of hyperglycemia correlates directly with lowered resistance to all types of infections.

The second major group of immunocompromising diseases includes those that interfere with host defense mechanisms, for example, leukemias, lymphomas, and many types of cancer. These diseases result in decreased white cell function and decreased antibody synthesis and production.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection attacks T lymphocytes, affecting a person’s resistance to viruses and other intracellular pathogens. Fortunately, odontogenic infections are caused largely by extracellular pathogens (bacteria). Therefore, HIV-seropositive individuals are able to combat odontogenic infections fairly well until acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) has progressed to advanced stages, when B lymphocytes are also severely impaired. Nonetheless, care for the HIV-seropositive patient with an odontogenic infection is usually more intensive than for the otherwise healthy patient.

Pharmaceuticals that compromise host defenses.

Patients taking certain drugs are also immunologically compromised. Cancer chemotherapeutic agents can decrease circulating white cell counts to low levels, commonly less than 1000 cells per milliliter (cells/mL). When this occurs, patients are unable to defend themselves effectively against bacterial invasion. Patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, usually for organ transplantation or autoimmune diseases, are compromised. The common drugs in these categories are cyclosporine, corticosteroids, tacrolimus (Prograf), and azathioprine (Imuran). These drugs decrease the function of T and B lymphocytes and immunoglobulin production. Thus, patients taking these medications are more likely to have severe infections. The immunosuppressive effects of some cancer chemotherapeutic agents can last for up to a year after therapy ends.

In summary, when evaluating a patient whose chief complaint may be an infection, the patient’s medical history should be carefully reviewed for the presence of diabetes, severe renal disease, alcoholism with malnutrition, leukemias and lymphomas, cancer chemotherapy, and immunosuppressive therapy of any kind. When the patient’s history includes any of these, the patient with an infection must be treated much more vigorously because the infection may spread more rapidly. Referral to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon for early and aggressive surgery to remove the cause and initiate parenteral antibiotic therapy must be considered.

Additionally, when a patient with a history of one of these problems is seen for routine oral surgical procedures, it may be necessary to provide the patient with prophylactic antibiotic therapy to decrease the risk of postoperative wound infection. Use of the guidelines and regimens for prevention of endocarditis published by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American Dental Association (ADA) is a practical way to manage this problem.

Principle 3: Determine Whether Patient Should Be Treated by General Dentist or Oral-Maxillofacial Surgeon

Most odontogenic infections seen by the dentist can be managed with the expectation of rapid resolution. Odontogenic infections, when treated with minor surgical procedures and antibiotics, if indicated, almost always respond rapidly. However, some odontogenic infections are potentially life threatening and require aggressive medical and surgical management. In these special situations, early recognition of the potential severity is essential, and these patients should be referred to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon for definitive management. As the specialist with the best training and experience in the management of severe odontogenic infections, the oral-maxillofacial surgeon can optimize the outcomes and minimize the complications of these infections. For some patients, hospitalization is required, whereas others can be managed as outpatients.

When a patient with an odontogenic infection comes for treatment, the dentist must have a set of criteria by which to judge the seriousness of the infection (Box 16-2). If some or all of these criteria are met, immediate referral must be considered.

Three main criteria indicate immediate referral to a hospital emergency room because of an impending threat to the airway. The first criterion is a history of a rapidly progressing infection. This means that the infection began 1 or 2 days before the interview and is growing rapidly worse, with increasing swelling, pain, and other associated signs and symptoms. This type of odontogenic infection may cause swelling in deep fascial spaces of the neck, which can compress and deviate the airway. The second criterion is difficulty breathing (dyspnea). Patients who have severe swelling of the soft tissue of the upper airway as the result of infection may have difficulty maintaining a patent airway. In these situations, the patient often will refuse to lie down, have muffled or distorted speech, and be obviously distressed by breathing difficulties. This patient should be referred directly to an emergency room because immediate surgical attention may be necessary to maintain an intact airway. The third urgent criterion is difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). Patients with acutely progressive deep fascial space infections may also have difficulty swallowing their saliva. Drooling is an ominous sign because the inability to control one’s secretions frequently indicates a narrowing of the oropharynx and the potential for acute airway obstruction. This patient should also be transported to the hospital emergency room immediately because surgical intervention or intubation may be required for airway maintenance. Definitive treatment of the infection can follow once the airway is secure.

Several other criteria should indicate referral to an oral-maxillofacial surgeon. Patients who have extraoral swellings such as buccal space infections or submandibular space infections may require extraoral surgical incision and drainage (I&D) as well as hospitalization. Next, although infection frequently causes an elevated temperature, a temperature higher than 101°F indicates a greater likelihood of severe infection, and this patient should be referred to the hospital. Another important sign is trismus, the inability to open the mouth widely. In odontogenic infections, trismus results from the involvement of the muscles of mastication by the inflammatory process. Mild trismus can be defined as a maximum interincisal opening between 20 and 30 mm; moderate trismus is an interincisal opening between 10 and 20 mm; and severe trismus is an interincisal opening of less than 10 mm.

Moderate or severe trismus may be an indication of the spread of the infection into the masticator space (surrounding the muscles of mastication) or, worse, either or both the lateral pharyngeal space and the retropharyngeal space surrounding the pharynx and the trachea. In this situation, referral to a specialist is necessary for evaluation of upper airway patency. In addition, systemic involvement of an odontogenic infection is an indication for referral. Patients with systemic involvement have a typical toxic facial appearance: glazed eyes, open mouth, and a dehydrated, sick appearance. When this is seen, the patient is usually fatigued, has a substantial amount of pain, has an elevated temperature, and is dehydrated. Finally, if the patient has compromised host defenses, he or she may have to be hospitalized. An oral-maxillofacial surgeon is qualified to admit the patient expeditiously to the hospital for definitive care.

In summary, within the first few minutes of the initial patient encounter, the three principles mentioned above allow the dentist to assess the severity of the infection, evaluate host defenses, and expeditiously decide on the best setting for the patient’s care. In doubtful situations, it is always best to err on the side of caution and refer the patient for a higher level of care. Appropriate decision making at this stage can prevent serious morbidity and the occasional mortality that still occur because of odontogenic infections.

Principle 4: Treat Infection Surgically

The primary principle of management of odontogenic infections is to perform surgical drainage and to remove the cause of the infection. Surgical treatment may range from something as straightforward as an endodontic access opening and extirpation of the necrotic tooth pulp to treatment as complex as the wide incision of the soft tissue in the submandibular and neck regions for a severe infection or even open drainage of the mediastinum.

The primary goal in surgical management of infection is to remove the cause of the infection, which is most commonly a necrotic pulp or deep periodonta/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses