Principles of Endodontic Surgery

Stuart E. Lieblich

Drainage of an Abscess

Endodontic surgery is the management or prevention of periradicular pathosis by a surgical approach. In general, this includes abscess drainage, periapical surgery, corrective surgery, intentional replantation, and root removal (Box 18-1).

Conventional endodontic treatment is generally a successful procedure; however, in 10% to 15% of cases, symptoms can persist or recur spontaneously. Such findings as a draining fistula or pain on mastication and the incidental finding of a radiolucency increasing in size indicate problems with the initial endodontic procedure. Many endodontic failures occur a year or more following the initial root canal treatment, often complicating a situation because a definitive restoration may have already been placed. This creates a higher “value” for the tooth because it now may be supporting a fixed partial denture.

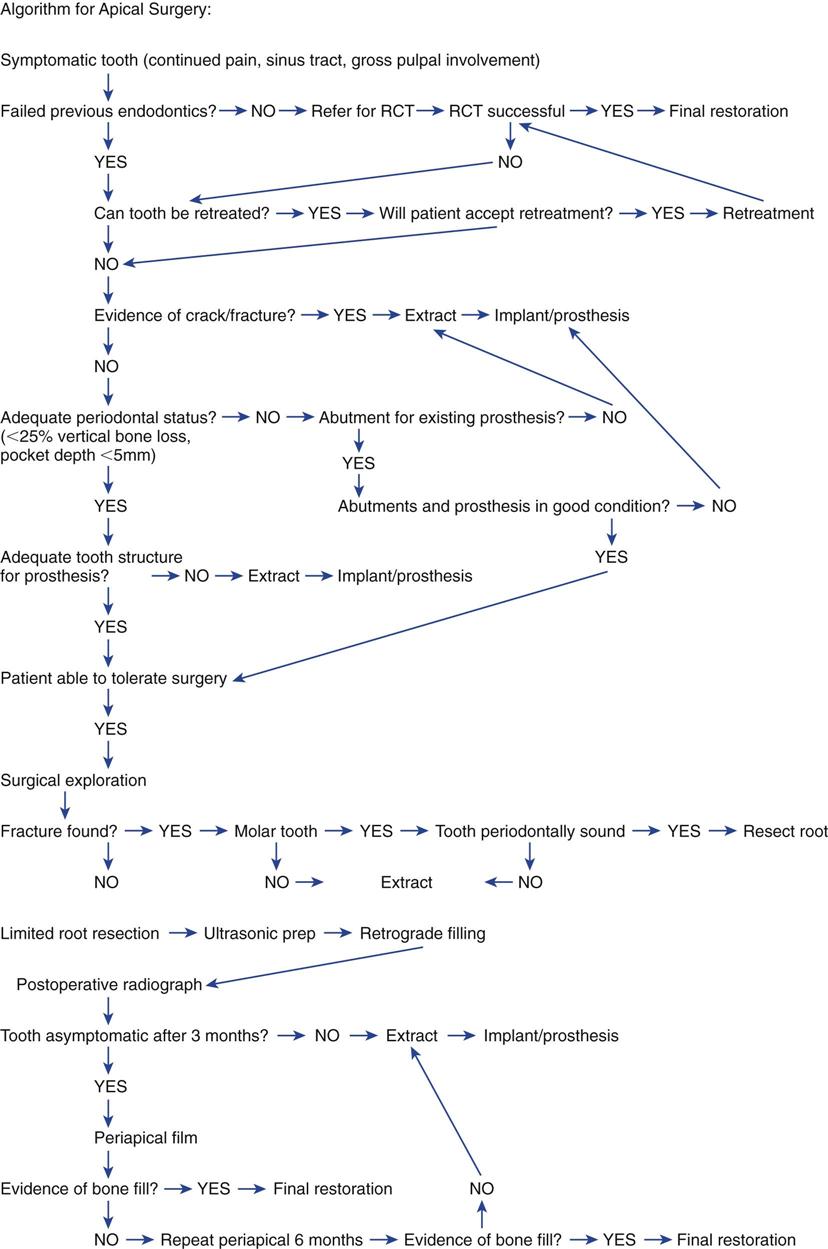

Surgery has traditionally been an important part of endodontic treatment. However, until recently, little research has focused on indications and contraindications, techniques, success and failure (i.e., long-term prognosis), wound healing, and materials and devices to augment procedures. Because of this lack of information, referral for surgery—such as the routine correction of failed endodontic treatment, removal of large lesions believed to be cysts, or single-visit root canal treatment—may have been inappropriate. A decision on whether to approach the case surgically or to consider orthograde (through the coronal portion of the tooth) endodontic retreatment is dictated by various clinical and anatomic situations. Other treatment options such as extraction of the tooth with placement of an implant may be preferred and actually may be associated with a higher long-term success rate. A recent consensus conference, however, concluded that endodontic therapy and implant procedures are considered equally successful. Additional procedures on the tooth, whether orthograde retreatment or periapical surgery, may reduce the long-term success rate of the tooth because each treatment is associated with additional tooth structure removal. When surgery is indicated, under the correct clinical situations it can maintain the tooth and its overlying restoration. Figure 18-1 is an algorithm to help guide the clinical decision as to whether endodontic surgery is indicated.

The purpose of this chapter is to present the indications and contraindications for endodontic surgery, diagnosis and treatment planning, and the basics of endodontic surgical techniques. Most of the procedures presented should be performed by specialists or, on occasion, by specially trained experienced generalists. Surgical approaches are often in proximity to anatomic structures such as the maxillary sinus (Box 18-2) and inferior alveolar nerve, and expertise in working around these structures is mandatory. Nonetheless, the general dentist must be skilled in diagnosis and treatment planning and must be able to recognize the procedures that are indicated in particular situations. When a patient is to be referred to a specialist for treatment, the general dentist must have sufficient knowledge to describe the surgical procedure to the patient. In addition, the generalist should assist in the follow-up care and long-term assessment of treatment outcomes. The final determination of success, as when a definitive final restoration should be placed, is often the responsibility of the referring dentist.

The procedures discussed in this chapter are drainage of an abscess, apical (i.e., periradicular) surgery, and corrective surgery.

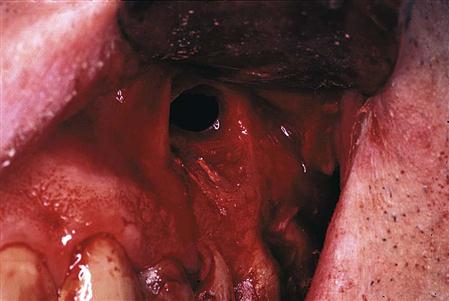

Drainage of an Abscess

Drainage releases purulent or hemorrhagic transudates and exudates from a focus of liquefaction necrosis (i.e., abscess). Draining of the abscess relieves pain, increases circulation, and removes a potent irritant. The abscess may be confined to bone or may have eroded through bone and the periosteum to invade soft tissue. Managing these intraoral or extraoral swellings by incision for drainage is reviewed in Chapters 16 and 17. Draining the infection does not eliminate the cause of the infection, so definitive treatment of the tooth is still needed.

An abscess in bone resulting from an infected tooth may be drained by two methods: (1) opening into the offending tooth coronally to obtain drainage through the pulp chamber and canal; and (2) a formal incision and drainage, with or without placement of a drain. An incision and drainage (I&D) is indicated if the spread of the infection is rapid, space involvement is evident, or if opening the tooth coronally does not yield obvious purulence. An I&D permits the dentist to obtain the pus for culture and sensitivity testing, when indicated. Most community-acquired endodontic infections do not require culture and sensitivity testing unless the patient is medically compromised or has failed to respond to an empirical course of antibiotics or if the infection was acquired in a hospital setting, which predisposes to resistant forms of bacteria.

Periapical Surgery

Periapical (i.e., periradicular) surgery includes a series of procedures performed to eliminate symptoms. Periapical surgery includes the following:

1. Appropriate exposure of the root and the apical region

2. Exploration of the root surface for fractures or other pathologic conditions

3. Curettage of the apical tissues

5. Retrograde preparation with the ultrasonic tips

6. Placement of the retrograde filling material

7. Appropriate flap closure to permit healing and minimize gingival recession

Indications

Following the completion of endodontics, symptoms associated with the tooth may lead to the recommendation for periapical surgery. Most commonly, patients have a chronic fistula and drainage. Other signs can include pain and the sudden onset of a vestibular space infection. Incidental findings of an increasing size of a radiolucent area found on routine radiographs may also lead to the decision to treat the periapical region surgically.

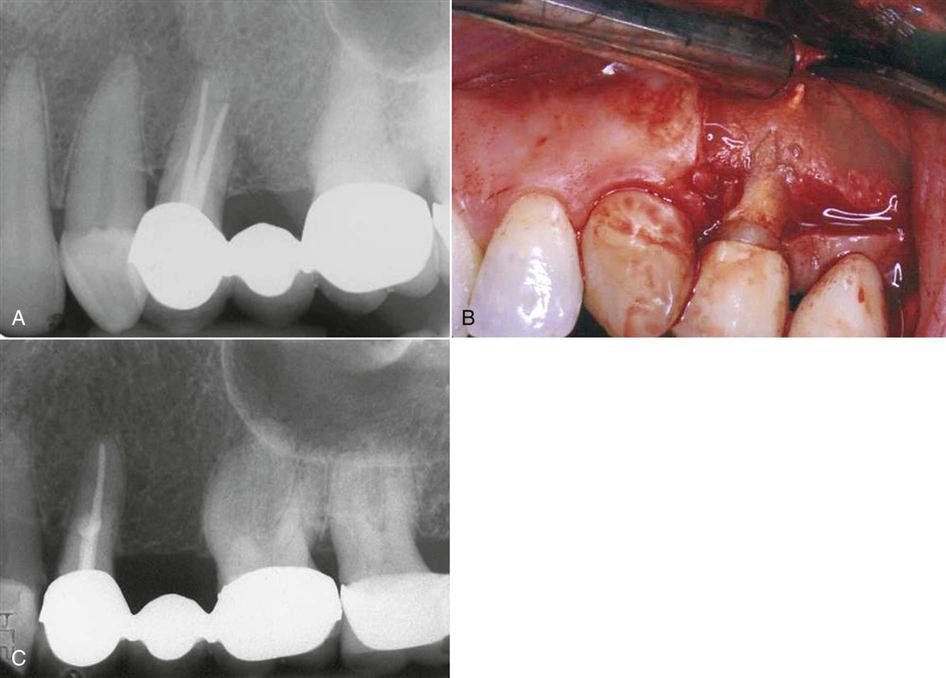

The success of apical surgery varies considerably, depending on the reason for and nature of the procedure. With failed root canal treatment, often re-treatment is not possible or a better result cannot be achieved by a coronal approach. If the cause of the failure cannot be identified, surgical exploration may be necessary (Figure 18-2). On occasion, an unusual entity in the periapical region requires surgical removal and biopsy for identification (Figure 18-3). Those indications for periapical surgery are discussed in the following sections (Box 18-3).

It is important to tell the patient preoperatively that endodontic surgery is exploratory. The precise surgical procedure is dictated by the clinical findings once the site is exposed and explored. For example, a fracture of a root may be noted, and the decision whether to resect the root or extract the tooth will need to be made intraoperatively. If the tooth is to be extracted, provisions for temporization must be made in advance if removal is an esthetic issue, or a decision must be made to close the flap and schedule the extraction in the future.

Anatomic problems.

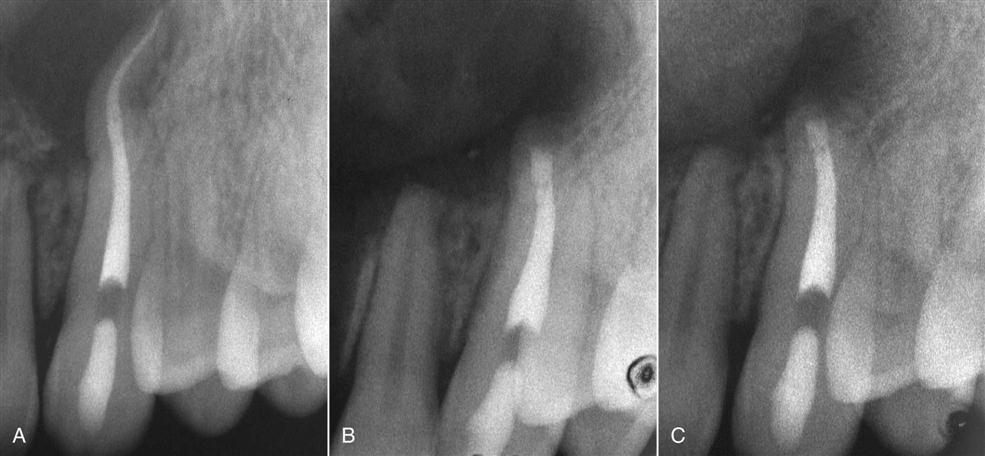

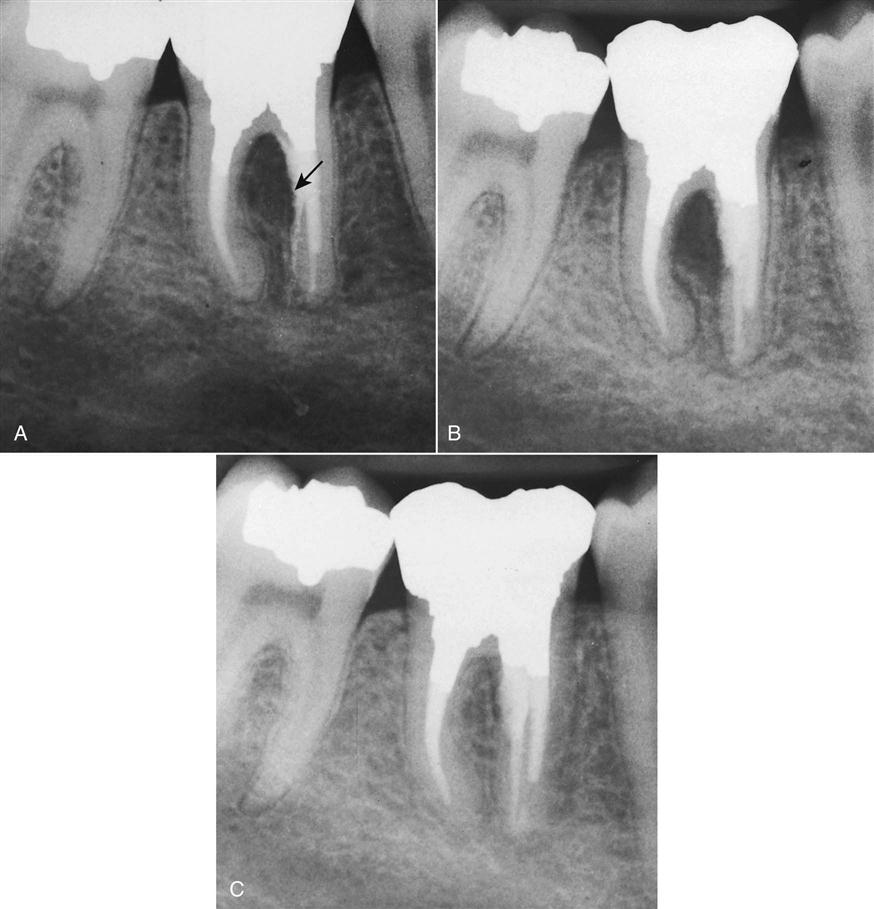

Calcifications or other blockages, severe root curvatures, or constricted canals (i.e., calcific metamorphosis) may compromise root canal treatment, that is, prevent instrumentation, obturation, or both (Figure 18-4). A nonobturated and cleaned canal may lead to failure because of continued apical leakage.

Although the outcome may be questionable, it is preferable to attempt conventional root canal treatment or re-treatment before apical surgery. If this is not possible, removing or resecting the uninstrumented and unfilled portion of the root and placing a root end filling may be necessary.

Restorative considerations.

Root canal re-treatment may be risky because of problems that may occur from attempting access through a restoration such as through a crown on a mandibular incisor. An opening could compromise retention of the restoration or perforate the root. Rather than attempt the root canal re-treatment, root resection and root end filling may successfully eliminate the symptoms associated with the tooth.

A common requirement for surgery is failed treatment on a tooth that has been restored with a post and core (Figure 18-5). Many posts are difficult to remove or may cause root fracture if an attempt at removal is made to re-treat the tooth.

Horizontal root fracture.

Occasionally, after a traumatic root fracture, the apical segment undergoes pulpal necrosis. Because pulpal necrosis cannot be predictably treated from a coronal approach, the apical segment is removed surgically after root canal treatment of the coronal portion (Figure 18-6).

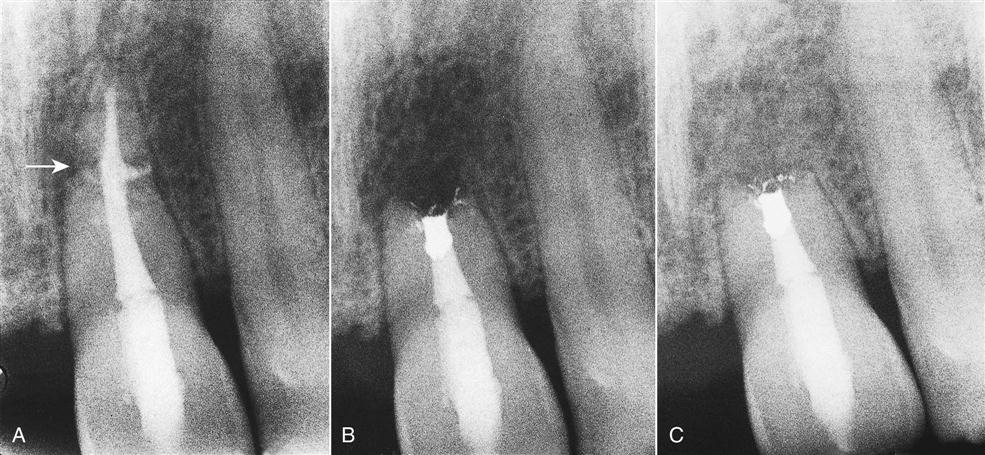

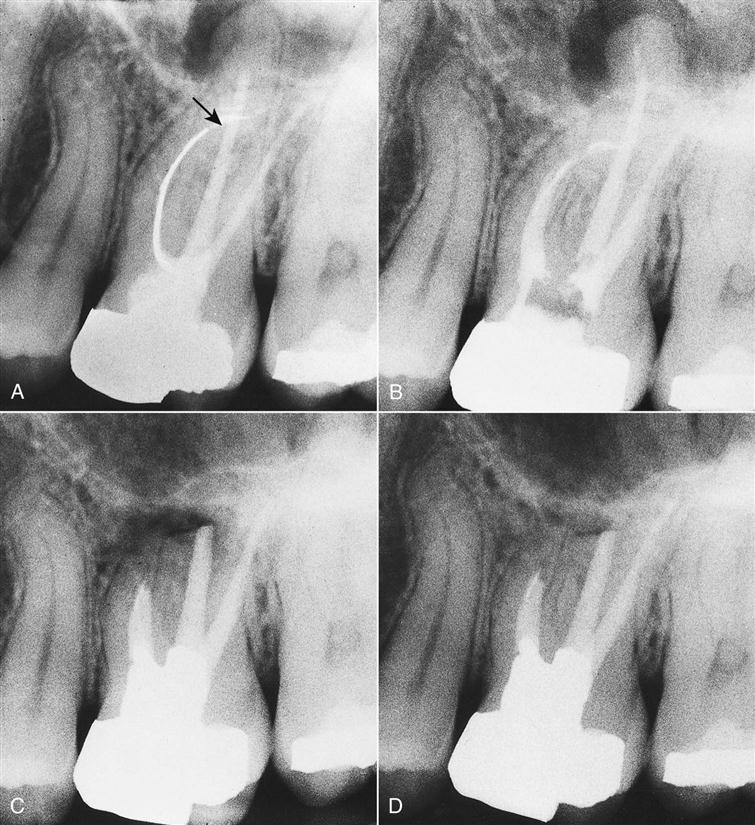

Irretrievable material in the canal.

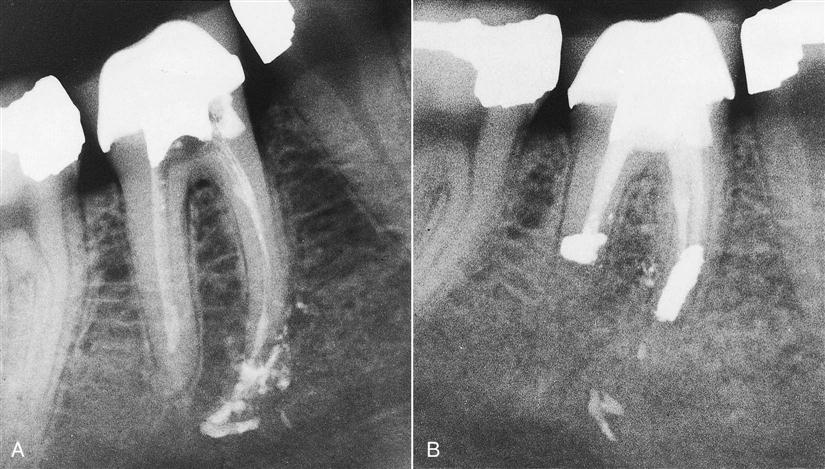

Canals are occasionally blocked by objects such as broken instruments (Figure 18-7), restorative materials, segments of posts, or other foreign objects. If evidence of apical pathosis is found, those materials can be removed surgically, usually with a portion of the root (Figure 18-8). A broken file can be left in the root canal system if the tooth remains asymptomatic.

Procedural error.

Broken instruments, ledging, gross overfills, and perforations may result in failure (Figures 18-9 and 18-10). Although overfilling is not in itself an indication for removal of the material, surgical correction is beneficial in these situations if the tooth becomes symptomatic. Because the obturation of the canal is often dense in these situations, surgical treatment has an excellent prognosis.

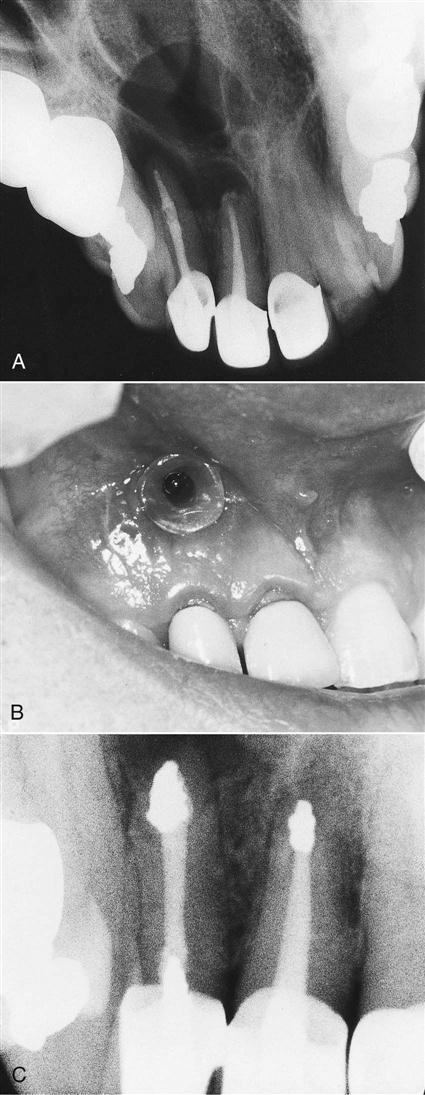

Large, unresolved lesions after root canal treatment.

Occasionally, very large periradicular lesions may enlarge after adequate débridement and obturation. These lesions are generally best resolved with decompression and limited curettage to avoid damaging adjacent structures such as the mandibular nerve (Figure 18-11). The continued apical leakage is the nidus for this expanding lesion, and root resection with the placement of an apical seal can resolve the lesion.

Contraindications (or Cautions)

If other options are available, periapical surgery may not be the preferred choice (Box 18-4).

Unidentified cause of treatment failure.

Relying on surgery to try to correct all root canal treatment failures could be labeled indiscriminate. An important consideration is to (1) identify the cause of failure and (2) design an appropriate corrective treatment plan. Often, orthograde re-treatment is indicated and offers the best chance of success. Surgery to correct a treatment failure for which the cause cannot be identified is often unsuccessful. Surgical management of all periapical pathoses, large periapical lesions, or both is often not necessary because they will resolve after appropriate root canal treatment. This includes lesions that may be cystic; these also usually heal after root canal treatment.

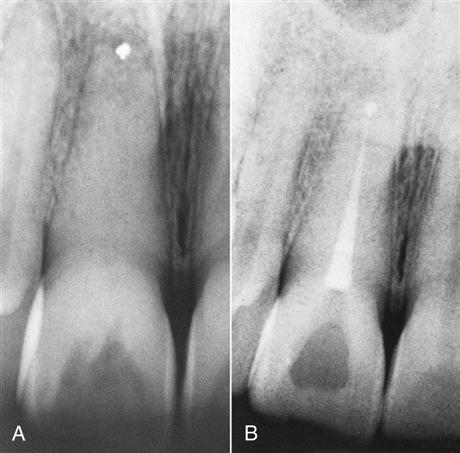

When conventional endodontic treatment is possible.

In most situations, orthograde conventional endodontic treatment is preferred (Figure 18-12). Surgery is not indicated just because débridement and obturation are in the same visit, although there has been a long-held, incorrect notion that single-visit treatment should be accompanied by surgery, particularly if a periradicular lesion is present.

Simultaneous root canal treatment and apical surgery.

Few situations occur in which simultaneous root canal therapy and apical surgery are indicated. Usually, an approach that includes both of these as a single procedure has no advantages. It is preferable to perform only the conventional treatment without the adjunctive apical surgery, and it is likely that it will have a better outcome. Another consideration is post-treatment symptoms. The level and incidence of pain after apical surgery is higher compared with root canal treatment. In some patients, the conventional root canal procedure is ineffective at eliminating symptoms. In this scenario, in spite of adequate instrumentation and antibiotics, purulent exudate from the tooth or a vestibular swelling is still present. A combined orthograde obturation with a simultaneous periapical surgery to curette the apical region and seal the tooth can successfully be coordinated and the symptoms resolved.

Anatomic considerations.

Although most oral structures do not interfere with a surgical approach, they must be considered. Expertise in operating around a structure such as the maxillary sinus or the mental nerve region is imperative before undertaking surgery in these regions. Exposure of the maxillary sinus, which occurs in most molar apical surgeries, is in itself not a complication but a known consequence of the surgery (Figure 18-13). Creating a sinus opening is neither unusual nor dangerous. However, caution is necessary not to introduce foreign objects into the opening and to remind the patient not to exert pressure by forcibly blowing the nose until the surgical wound has healed (for 2 weeks). Correct flap design is also crucial to prevent the development of an oral–antral communication. The sulcular flap keeps the incision line far from the sinus opening, thus allowing spontaneous healing.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses