Introduction to Dental Trauma

Managing Traumatic Injuries in the Primary Dentition

Etiology and Epidemiology of Trauma in the Primary Dentition

Classification of Injuries to Teeth

Injuries to the Hard Dental Tissues

Cracks and Fractures of the Enamel and Dentin Without Pulp Exposure

1. Knowledgeable in the techniques for managing traumatic injuries

2. Readily available during and after office hours to provide treatment

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a straightforward approach to managing dental injuries in the primary dentition. Techniques for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care are described. Fundamental issues covered in this chapter, such as classification of injuries, history, examination, and pathologic sequelae of trauma, pertain to both the primary and permanent dentitions. Chapter 34 will focus on management of injuries to young permanent teeth and will refer to this chapter for the information just noted. The principles gleaned from both chapters should enable the dentist to manage the great majority of dental injuries encountered in children.

Etiology and Epidemiology of Trauma in the Primary Dentition

Although reports of injuries in preschool children presenting for dental treatment show that the majority of children suffer from luxation injuries,1,2 epidemiologic studies in the community show that crown fractures are the most common injury to the primary teeth.3–5 These injuries, however, may result in only minor inconveniences that do not motivate parents to seek professional dental advice.

By the age of 5 years, up to 40% of boys and 30% of girls have experienced traumatic injuries to their teeth.6 The peak age of injuries to the primary teeth is 2 to 4 years when children are developing mobility skills. Children with protruding incisors, as in developing class II malocclusions, are two to three times more likely to suffer dental trauma than children with normal incisal overjets.

Another major cause of dental injuries in young children is automobile accidents. Unrestrained children who are seated or standing often hit the dashboard or windshield when the car is stopped suddenly. All states now have laws mandating use of child restraints in automobiles, and it is hoped that universal adoption of these laws will decrease the incidence of all trauma to children in automobile accidents.7

Children with chronic seizure disorders experience an increased incidence of dental trauma. Frequently, these high-risk children wear protective headgear, and the fabrication of custom mouth guards for them is indicated (see Chapter 40).

Another serious cause of dental injuries to young children is child abuse. Often overlooked by the dental profession, up to 50% of abused children suffer injuries to the head and neck. Cardinal signs of abuse are injuries in various stages of healing, tears of labial frena, repeated injuries, and injuries whose clinical presentation is not consistent with the history presented by the parent.3 Battered children frequently lie to protect their parents or out of fear of retaliation. Dentists are required by law to report cases of suspected child abuse (see Chapter 1 for more specific details).

Classification of Injuries to Teeth

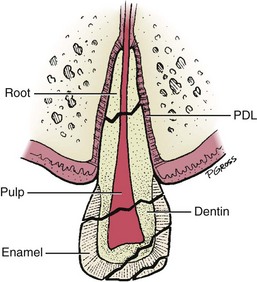

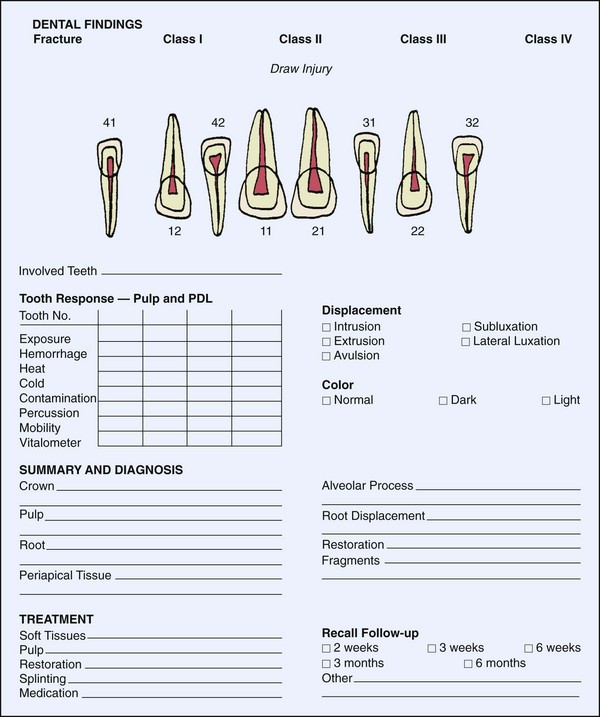

Tooth fractures may involve the crown, root, or both (Figures 15-1 to 15-3; see also Figures 34-1 to 34-3). Fractures of the crown may be limited to the enamel, may involve the dentin, or may include the pulp. Injury to the pulp is the most complicated and demanding to manage.

As just mentioned, luxation (displacement) injuries are the most common types of injuries to primary teeth that are treated in the dental office. These injuries damage supporting structures of the teeth, which include the periodontal ligament (PDL) and the alveolar bone (see Figure 15-1). The PDL is the physiologic “hammock” that supports the tooth in its socket. Maintaining its vitality is the primary objective in the management of all luxation injuries. Several types of luxation injury occur.6

1. Concussion: The tooth is not mobile and is not displaced. The PDL absorbs the injury and is inflamed, which leaves the tooth tender to biting pressure and percussion.

2. Subluxation: The tooth is loosened but is not displaced from its socket.

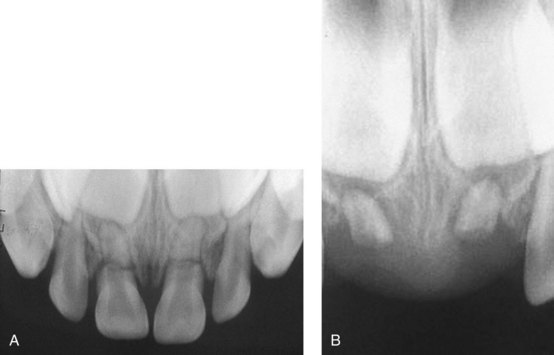

3. Intrusion: The tooth is driven into its socket. This compresses the PDL and commonly causes a crushing fracture of the alveolar socket. See Figures 15-4 and 34-15.

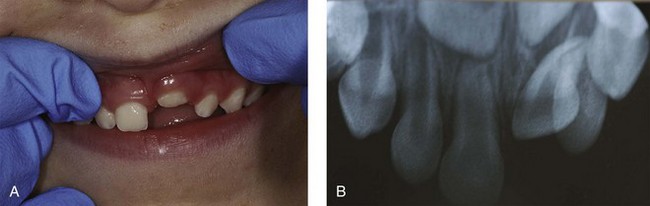

4. Extrusion: This is a central dislocation of the tooth from its socket (Figures 15-5 and 34-16, A). The PDL is usually torn in this injury.

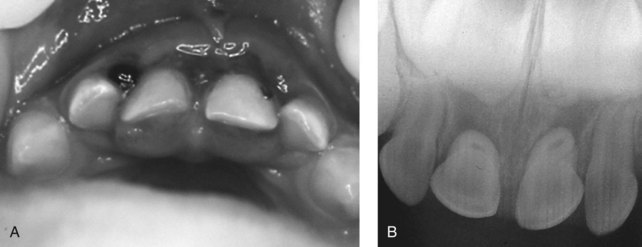

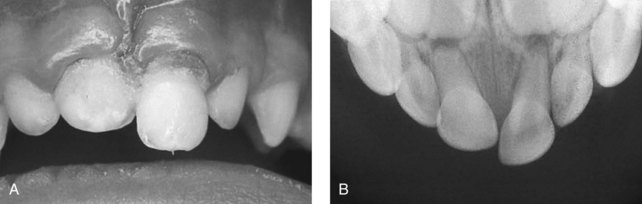

5. Lateral luxation: The tooth is displaced in a labial, lingual, or lateral direction. The PDL is torn, and contusion or fracture of the supporting alveolar bone occurs (Figures 15-6 and 34-16, B).

FIGURE 15-6 Lingual luxation of both maxillary primary central incisors. A, Clinical view. B, Radiographic view.

FIGURE 15-6 Lingual luxation of both maxillary primary central incisors. A, Clinical view. B, Radiographic view.

6. Avulsion: The tooth is completely displaced from the alveolus. The PDL is severed, and fractures of the alveolus may occur (Figures 15-7 and 34-17).

History

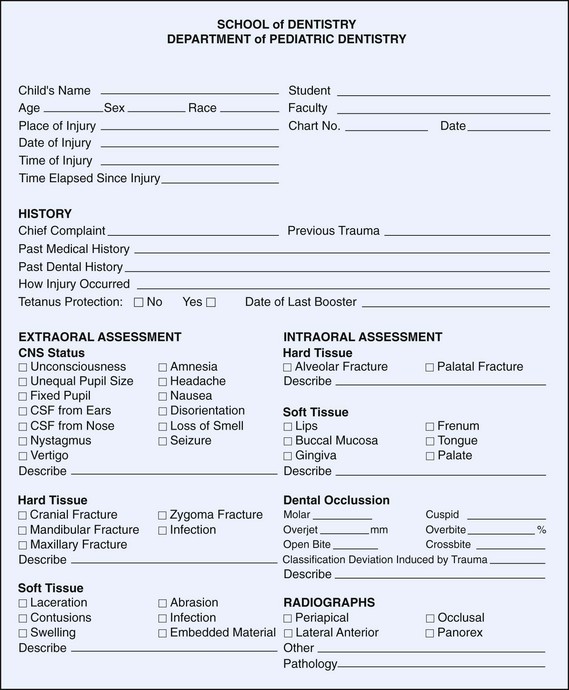

Obtaining an adequate medical and dental history is essential to proper diagnosis and treatment. The medical history should already be on record if the child suffering an injury is brought to his or her regular dentist. Frequently, however, a parent will take an injured child to the closest dentist or to one known to treat children. Thus, with the confusion of a young injured child entering the office for possibly the first time and disrupting the day’s schedule, the potential to forget to gather important historical information is great. The use of a trauma assessment form to help record data and organize the management of care is highly recommended (Figure 15-8).

Medical History

The issue of tetanus protection is particularly important when a child has suffered a dirty wound (an avulsion), a deep laceration, or an intrusion injury in which soil is embedded in the tissues. Wounds containing necrotic tissue, dirt, and foreign material should be cleaned and debrided as an essential part of tetanus prophylaxis. Children acquire active immunity through a series of five injections of adsorbed tetanus toxoid, usually completed by the age of 4 to 6 years. These are normally administered as part of the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunizations. Children should then receive a booster of tetanus toxoid at 11 to 12 years of age and again 5 years later.8 An increasing number of reports have indicated that children in the United States are not receiving their childhood immunizations appropriately. If there is any question about the adequacy of a child’s tetanus protection, the child’s physician should immediately be consulted.

History of the Dental Injury

How the accident occurred obviously provides the dentist with the most information regarding severity. Serious head injuries should be ruled out by the dentist’s asking if the child lost consciousness, has vomited, or is disoriented as a result of the accident. Positive findings indicate potential central nervous system injury, and medical consultation should be immediately obtained.9 Tecklenburg and Wright note that significant head injuries can lead to symptoms many hours after the initial trauma, and they caution parents to watch for the signs noted previously for 24 hours, which includes waking the child every 2 to 3 hours through the night.10

Clinical Examination

Extraoral Examination

A complete examination should rule out injuries to the child’s facial bones.11 The facial skeleton should be palpated to determine discontinuities of facial bones. Extraoral wounds and bruises should be recorded. The temporomandibular joints should be palpated, and any swelling, clicking, or crepitus should be noted. Mandibular function in all excursive movements should be checked. Any stiffness or pain in the child’s neck necessitates immediate referral to a physician to rule out cervical spine injury.

Radiographic Examination

Radiographic Techniques

There is no “standard series” of radiographs for dental injuries. All films taken should clearly show the apical areas of traumatized teeth (see Figure 18-15, C). In cases in which root fractures are suspected, a second or third radiograph should be made from slightly different angles both vertically and horizontally to verify the location and extent of the fracture.

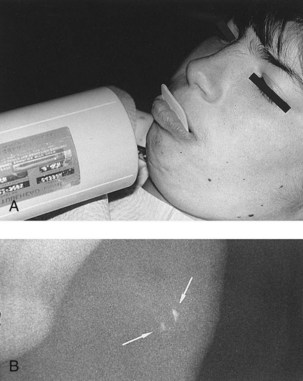

To determine the presence of foreign bodies such as tooth fragments in the lips or tongue, one fourth of the normal exposure time is used. The film is placed beneath the tissue to be examined, and the radiograph is exposed (Figure 15-9).

Emergency Care

Injuries to the Hard Dental Tissues

Cracks and Fractures of the Enamel and Dentin Without Pulp Exposure

Enamel cracks and small fractures are common findings in primary teeth (see Figure 15-2). It is believed that even fractures exposing dentin in primary teeth have no deleterious effect on the pulp and need not be covered. In the case of larger fractures, treatment is often indicated to restore aesthetics. Various methods have been suggested to restore the fractured crown, including use of strip crowns, preformed aesthetic crowns, and open-faced steel crowns (see Chapter 21).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline

FIGURE 15-1

FIGURE 15-1

FIGURE 15-2

FIGURE 15-2

FIGURE 15-3

FIGURE 15-3

FIGURE 15-4

FIGURE 15-4

FIGURE 15-5

FIGURE 15-5

FIGURE 15-7

FIGURE 15-7

FIGURE 15-8

FIGURE 15-8

FIGURE 15-9

FIGURE 15-9